POST-PARTY DEPRESSION A Roundtable Discussion on the Dynamics of the Art Market with Dirk Boll, Marc Glimcher, Nicole Hackert, and Anne Helmreich, moderated by Natasha Degen

Pietro Antonio Martini, “Salon du Louvre,” 1787

NATASHA DEGEN: With this issue of TEXTE ZUR KUNST, Isabelle Graw proposes a provocative idea: that the art system may be undergoing a transformation comparable to that of the late 19th century, when the Salon began to lose ground to what Cynthia and Harrison White called the dealer-critic system. It was around this time that both the commercial gallery and art criticism emerged in their modern forms, in parallel with one another. How do we understand this historical shift from today’s vantage?

ANNE HELMREICH: In White and White’s theory, you have the Salon system in 19th-century France, which favored single works of art, and critics who wrote about those single works of art. And then the dealer-critic system was a shift where you now had dealers nurturing an artist’s career. And alongside that was the critic, not just focusing on the smash hit of the year but really trying to think more about the evolution of an artist’s style or a movement’s style. So that’s their operating theory. But it hasn’t totally held up over time as people investigate more; I think we can find lots of examples of single works of art that get lots of attention in the dealer-critic system, and the dealers were also active in criticism. For example, a dealer in late 19th-century London I’ve studied was also the editor of the main art journal at the time. We think about those roles as rather fixed, but they’re actually pretty fluid.

Paul Marsan, Paul Durand-Ruel in his gallery, ca. 1910

MARC GLIMCHER: Whoever was responsible, artist or dealer, this moment saw a shift to a larger audience thinking about an artist’s career. The gallery system at the time, with Paul Durand-Ruel and Nathan Wildenstein and the rise of the single-artist show, created the idea of a time-limited run, if you will. So that engaged a larger public in looking at, say, a group of Gustave Caillebottes, which starts to push the audience toward career observation rather than just art observation.

HELMREICH: You get the rise of retrospectives organized by dealers in this period, too, and they see a real response. I’m thinking about artists like James McNeill Whistler or Claude Monet. They see an opportunity to work with collectors to bring those exhibitions together, and to put works back out into circulation or visibility. So it really becomes this kind of collaborative effort between artists, dealers, and collectors.

DEGEN: One defining feature of this model was that dealers and critics shared incentives that encouraged them to champion the new, leading both to promote the avant-garde. This makes me wonder whether an underlying value system emerged alongside the rise of the commercial gallery and the development of a more partisan mode of art criticism.

GLIMCHER: I think that’s true. A Hegelian dialectic introduces itself into school and counter-school, and the critics start codifying this group versus that group, and the artists engage in that logic: This group is right, that group is wrong; this group is old fashioned, that group is new. Up until about 1980, that was the game. Critics were already losing power in the ’80s, as that kind of dialectical procession from Abstract Expressionism to Pop, Minimalism to Conceptualism, etc., started to fall apart with the Pictures Generation and the Neo-Expressionists. And I think it had a lot to do with other societal forces, such as when certain artists gained a critical mass of celebrity. Something happened, and the critics started to lose their power.

DEGEN: Art publications were also covering the market more by the ’80s, and critics were writing catalogue essays for commercial galleries, which changed their role.

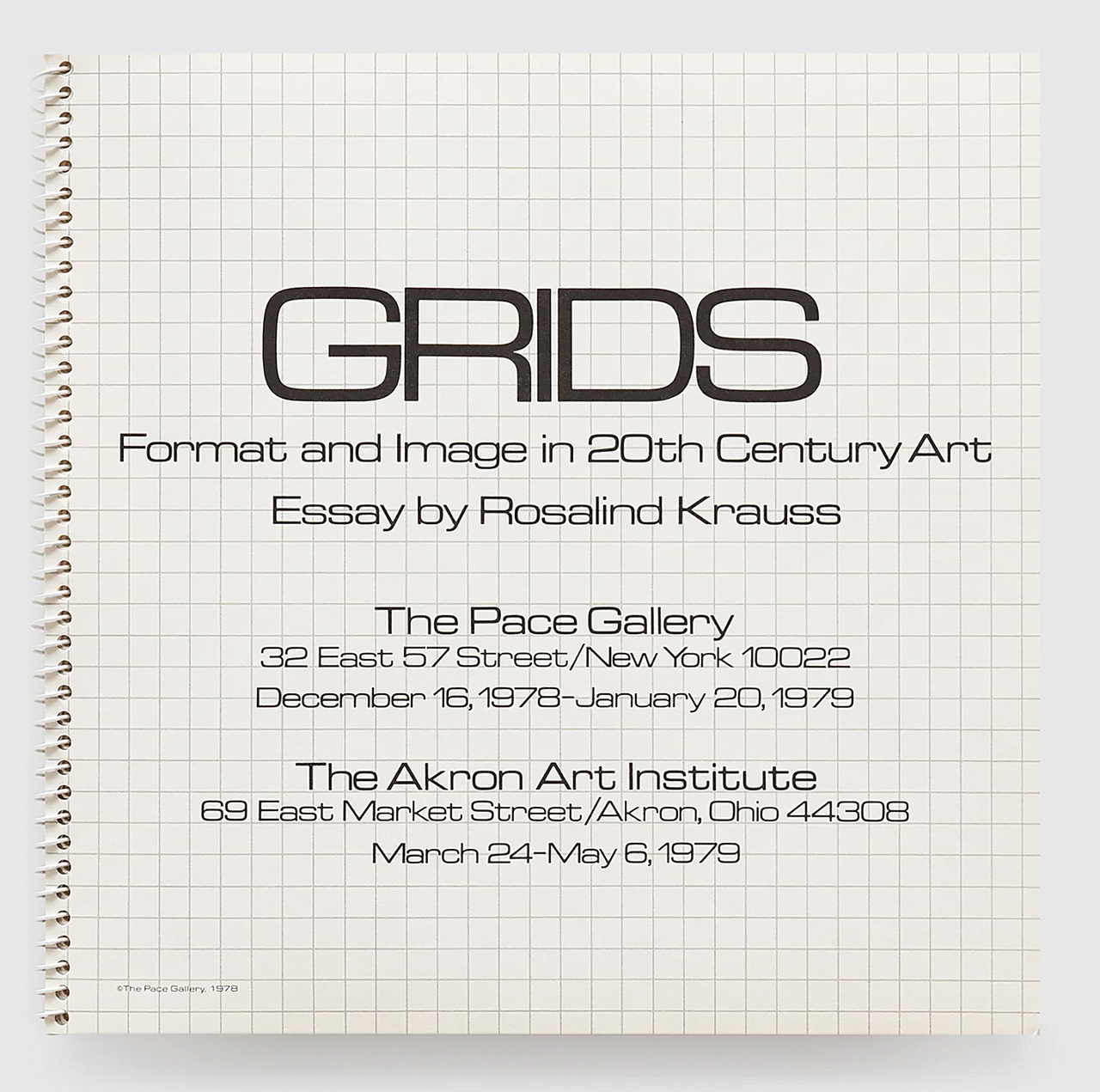

Pace Gallery, “Grids: Format and Image in 20th Century Art,” 1978

GLIMCHER: By the mid-’80s we were intentionally hiring critics to do our catalogues. I remember that was something that Rosalind Krauss would absolutely not do, and then something that Rosalind Krauss would absolutely do. I remember conversations with my father where he felt shocked that she had said yes.

DEGEN: Dealers paid critics more than magazines did. So there was a clear financial incentive, which has become even more pronounced since, with the decline of print media. The era of the full-time salaried critic is pretty much behind us. Anne, I’m sure you have thoughts on this as well.

HELMREICH: Well, there’s also a split with the more academically inclined journals like October, which have their own funding model. I’m thinking about Artforum and almost mentally picturing the library shelf – they start to get slimmer and slimmer, don’t they?

NICOLE HACKERT: Totally. But I do believe it’s still quite powerful if artists have a theoretical counterpart.

GLIMCHER: There is another shift, which was from critic to curator, where the curator gets the power that the critic previously had because the curator is able to create a result for the public. The result that the critic produces, the work product, is a piece of writing. Whereas the work product of the curator is an event, an experience. And it’s very important to note the decline of the power of writing versus the power of experience, which also plays a huge role. It shifts the power to the curators because we don’t consume words the same way that we consume pictures.

HELMREICH: If we looked at art-school pedagogy today, you would see MFA students being encouraged to form those networks with writers who can write about their work, but also to form those networks with curators, right?

HACKERT: I agree with Marc that the curators are now way more important in supporting an artist’s career than critics are. Because the independent critic can probably no longer persist. I can’t think of any contemporary superstar where I would know, “This is very obviously the writer who supported them,” like Benjamin Buchloh did with Gerhard Richter.

GLIMCHER: But a curator is unlikely to have those conversations with an artist, like “What are you doing?” or “You’re losing your mind.” A curator who supports an artist and is on, you know, team Julie Mehretu, if they have a problem with Julie’s new work, they’re not going to talk about it in public. So that intra-career incisiveness where Peter Schjeldahl’s going to tell Brice Marden that he’s gone in the wrong direction, and Brice is going to have a nervous breakdown but then change direction … I don’t see how that happens. It’s whispered, and then tragically we’re all waiting for the auction house to punish these artists.

Mike Goldwater, Sunday Brunch viewing for Post-War and Contemporary Art, Christie’s, London, 2004

HACKERT: Since this roundtable was initiated by TZK, it’s interesting to note that this magazine became super powerful at the beginning of the ’90s and supported this group of artists that you could subsume under the banner of institutional critique. I think this was probably the last time that a critical organ like TZK would have been able to rise while also creating and supporting artists’ careers. And not only by applauding. It was real criticism, which is unheard of nowadays.

GLIMCHER: There’s another interesting phenomenon, of art critics becoming art market critics, or art world critics. You know, Jerry Saltz can certainly be the poster child or whipping boy for that move from language about art to language about the art business. And I would say that now in social media and so forth, certainly this year, there’s more criticism and discussion of galleries or auction houses than there is of artists and art.

DIRK BOLL: Because it has become an industry. And so people are interested in the structure behind it, which wasn’t previously the case, because the companies weren’t that large and didn’t work on an industrial level with industrial tools. And since these companies did start doing that, the wider public got interested. The big boom in contemporary art was in the ’80s, but it happened in the galleries and not on the secondary market. But in the auction houses and the secondary market, there was the discovery of art as an asset class. The party for all participants was over in 1990, and when the market recovered, these two forms merged. So all this happened after art had been seen or recognized as an asset class and vehicle for investment and speculation, and then auctions made trends visible and prices transparent, and all of a sudden contemporary art was recognized and accepted as another tool in the box. I would say that happened 10 years later, in the late ’90s.

GLIMCHER: It’s important to note that this break, which emerged around ’90 to ’93, resulted in a completely different art world, where the gallery and auction-house models became fused. Dirk’s absolutely right there. That’s the absolute turning point in the fall of the dealer-critic system, the arrival of the auction house in the retail market.

Jerry Saltz, 2011

HACKERT: Auctions for contemporary art definitely existed in the ’90s, but they played basically no role – especially when we started, because our artists were also just starting off. I remember the first auction that we were somewhat involved in, through a German collector. We were still representing Peter Doig then, and so he was auctioning Doig, Sean Landers, Raymond Pettibon. And for me, that was the turning point, around 1997. The Doig went for like 270,000 pounds and we thought, oh my goodness, because we had sold the work a few years earlier for 20,000 deutschmarks. So that was quite something. The secondary market numbers were not ridiculous from our point of view now, but what the collector made in relation to what he invested was just incredible. Still, I don’t remember it causing any stress, because he had personal or financial reasons for selling, and we were able to convey this to the artists. The stress came later. Issues with flipping and non-resale contracts only started becoming a big thing in the early 2000s, maybe even after 2010.

DEGEN: Dirk, what were these years like at the auction house?

BOLL: Well, I was interning in 1997 and then I was hired in ’98. I started in London, in a department that was then called Contemporary Art, which covered everything that had been created post-1945. Back then, the powerful departments were what we now call “classic,” so especially Old Masters, but also to a lesser degree decorative arts, and I think Impressionist was third. I remember the discussions in my early London days about whether we should introduce the term postwar art and essentially differentiate between things that had been created decades ago. There was gossip that Brett Gorvy, who was running the London team back then, would say that Richter was utterly upset that his works were offered in a sale that was labeled postwar because he was very much alive and he felt very contemporary. I also remember that many people were quite upset on the collecting side because with the newly introduced format of a contemporary evening sale, that must have been in ’99, all of a sudden we had two evening sales presenting art produced after 1945. And many, many buyers would say in the old days that a Christie’s evening sale appearance was a rubber stamp for quality. So you could just kind of unthinkingly rely on Christie’s judgment, and then suddenly Christie’s would present fairly young, kind of wet canvases in an evening sale. So this platform was no longer the differentiator for that type of shopper. And I do remember that there was a lot of discussion around that among my colleagues. That period of having two evening sales and two teams didn’t last long, so when the internet bubble burst in late 2000, this all came to an end. There simply wasn’t enough material or demand to maintain that structure, and after that the department was called Postwar and Contemporary, just to be renamed and restructured in 2020 into a so-called cluster, now called 20/21. But I realized that what we now call 20/21, which covers Impressionist to postwar, accounts for almost three quarters of Christie’s turnover today. So the postwar share went from 5 to maybe 55 percent in 25 years, which shows you how the market has moved.

“Peter Doig: Country Rock,” Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin, 1999

DEGEN: And how did the emergence of auction houses as major players in contemporary art affect galleries? I imagine it didn’t just impact the galleries’ market share but also changed the kind of control they could exert over how their artists’ markets developed.

GLIMCHER: You know, art is a Veblen good, right? So a Veblen good is any good where when the price goes up, demand goes up – Ferraris, art, diamonds, whatever. And a Veblen good is always managed by a cartel, because the market can’t manage itself and will naturally go into a cycle of boom and bust if higher prices lead to higher demand. And the art market up until the ’70s was very much managed as a cartel. The rise of an artist’s prices from show to show was very much limited to 10 percent, and those shows were limited to 36-month cycles at the most, if not 48. There was also a kind of code among all the secondary market dealers, and there was a lot of behind-the-scenes conversation about prices, profit margins, etc. Although that system did start to break down with figures like Mary Boone in the ’80s, the primary market was relatively unaffected, because the primary market dealers were still not significant in the secondary market at that point. Pace was kind of the only gallery that was dealing in both primary and secondary in the ’70s and ’80s. But one has to recognize that in the mid-’90s, after that huge recession and the breakdown of the market, the “Gagosian doctrine” came into place. Which was to say, we don’t need any rules. He was rejected by the cartel, and he turned around and said, Well, I’m not going to play by your rules, and I’ll buy it for a million and sell it for two million if I can. And as soon as the cartel rules break down, it’s a free-for-all. And obviously with globalization and the growth of wealth and everything, up until a couple of years ago, you would hear people saying that this just can’t last. But obviously it did last for a very long time.

DEGEN: This is the first time since the advent of the “Gagosian doctrine” that we’re seeing profound upheaval in the market. What kind of change is the current downturn bringing about? Is this a cyclical reset or a sign of something more lasting, like a generational shift in taste?

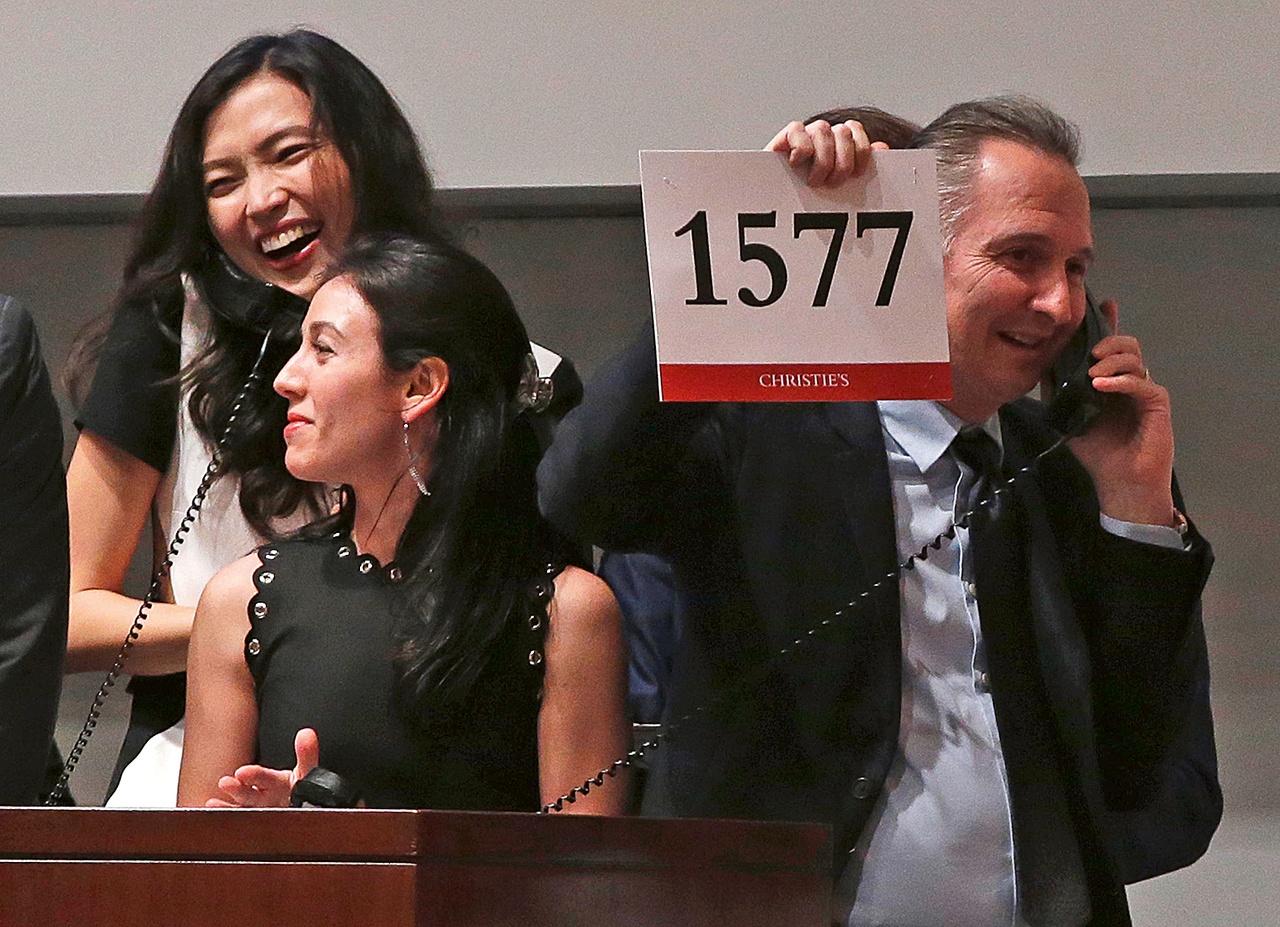

John Angelillo, Brett Gorvy sealing a deal at Christie’s, New York, 2015

BOLL: It’s so much easier to understand and judge what kind of crisis it was after it’s over. The auction is tough because you need the demand right here and now; you can’t say we’ll just put it up for sale and then see what happens. Those days are over. I totally refuse to believe that younger generations don’t collect anymore or aren’t interested in art anymore. I simply cannot believe that, and I don’t see it in my daily work. So I’m amused to see how that whole system of daily reporting on the state of the art market, which we all enjoy when the curves go up, all of a sudden cannot help but observe a big crisis and the end of collecting the very second the market has a bit of a pause or curves go down. As Marc was saying, the interest in art has been replaced at least partly by the interest in the industry or in the structure of the market, and you could also say that art criticism has been replaced by criticism of the industry and its structure. And this is what we see on a daily basis.

HELMREICH: We think about this great industrial complex, this great expansion of the market, but at the time that begins to happen, around the 2000s, there are people who feel like they can’t participate in it, or choose not to, and who create these alternative ways of thinking and expressing themselves that are proving to be really resilient. In terms of art criticism, I’m thinking of The Brooklyn Rail, or of Glasstire in Texas. Both emerged in the early 2000s to give voice to artists in a particular place or region, and I see them as still being very active, even amid this industrial market downturn. So perhaps one curve goes down, but another one keeps moving along.

BOLL: Maybe the dealer-critic system has been replaced by the industry opinion-leader system. The opinion-leader is no longer just the art critic and the curator. It’s a wider range of people: the art critic, yes, but also the big collector, the owner of the private museum, the gallery that has an audience and visibility and makes decisions on whom to take on board. Clearly some sort of media, clearly some sort of social media, and the community as such.

HACKERT: But for somebody looking at it from the outside, that still looks like an inaccessible network. Young artists would probably think, Okay, well, this is a network that is probably even harder to get access to since it’s not only a critic that I need to convince of the quality of my work.

BOLL: I would turn that around, Nicole. I would say that rather than needing to convince the critic, I now have a wide range of access possibilities. It can be the critic, or the curator, or the private collector.

John Angelillo, Brett Gorvy sealing a deal at Christie’s, New York, 2015

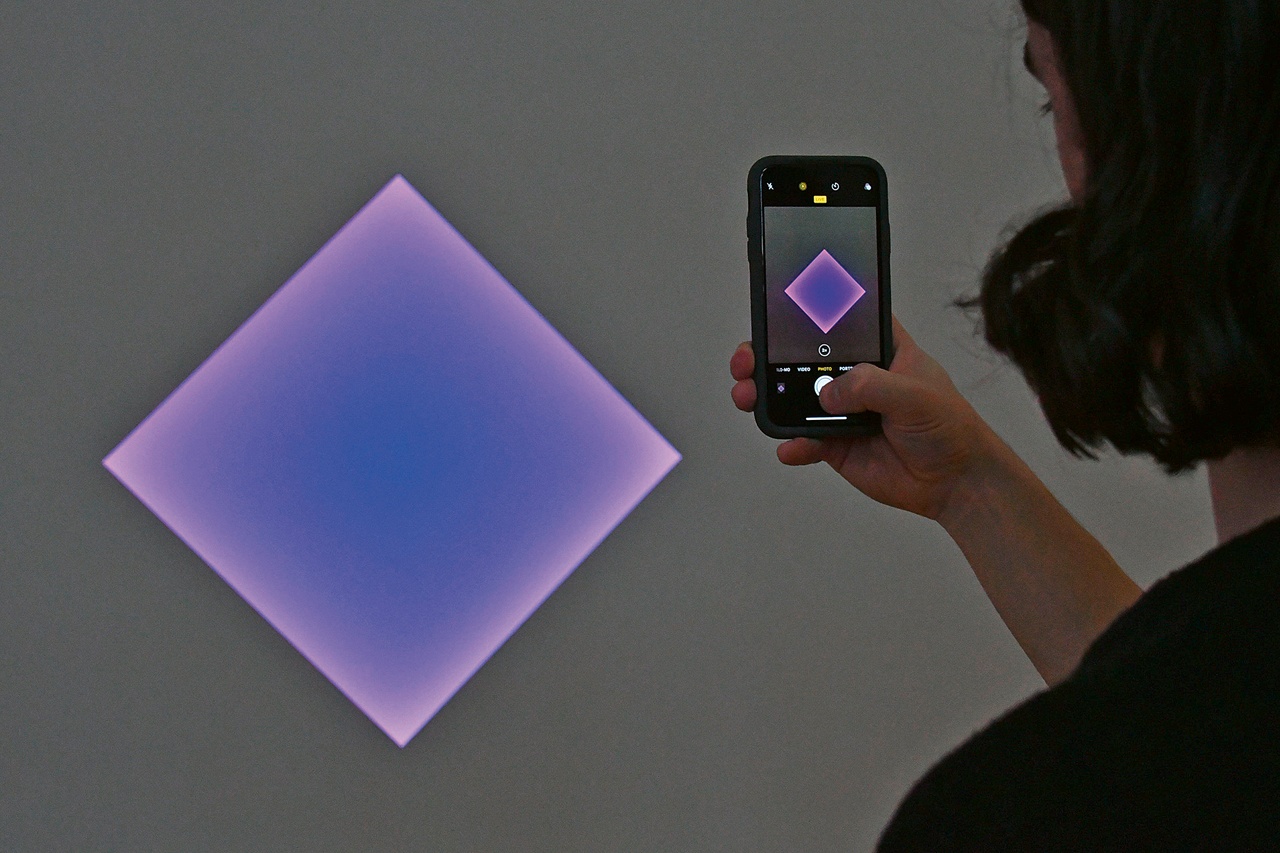

GLIMCHER: There’s also a new voice, which is the voice of the cultural consumer. The best estimate is that there are really about 200,000 people who could be art collectors. And of those people, there are about 50,000 who are active art collectors. So that’s people with a net worth of above $100 million. But people with a net worth in the world above $1 million, I think, is about 25 million people, and people who consider themselves cultural consumers, the current numbers from museums and so forth put that at about 45 million people in the world. When our Instagram account passed a million people, we were just flabbergasted. We might have a thousand clients who are really active. Maybe we have 8,000 or 9,000 people in a database, and maybe we’re selling 2,000 objects a year, which is a lot. Or we used to. But we have a million followers now, maybe 1.2 million or something like that. This was my fantasy with Superblue, to find a way to sell tickets to a James Turrell so that Turrell would have an alternative revenue source from those cultural consumers. And I got killed for it. But just like in ’93 and ’94, something’s getting rewritten now.

HACKERT: I think so, too. When I entered the market, what you would probably call cultural consumers now were people with an income that was slightly above normal – you know, a professor – and they were able to buy art. I haven’t seen these kinds of collectors in a long time. And I’m always like, arms wide open, approach us.

GLIMCHER: Right. But their voices still count. Now those cultural consumers have strong opinions and vote with their feet, as Glenn Lowry often says. And I think the collectors are listening to those 25 or 45 million people. Even if they’re not buying art, they still have an impact.

HACKERT: Yeah, and that’s a paradigmatic change, because they used to pride themselves on having been the first to buy, often because of economics – you had to be early if you didn’t have such a high budget. I simply don’t see that anymore.

BOLL: Well, I think because the entry level is now too expensive …

GLIMCHER: It’s too expensive.

HACKERT: We also lost people because of unfulfilled promises. A lot of people without any knowledge or expertise entered the market hoping for turnover, and it’s no longer happening. And if they were gamblers by nature and maybe did win when they first put something back on the secondary market, then they might have lost their luck with number three or four.

GLIMCHER: We over-monetized it, and it didn’t perform. We invited everybody backstage at the magic show.

DEGEN: The idea that only established gatekeepers determine art’s value has been showing cracks for a while now. Anne, it makes me think of the Salon system, which was so dominant in its time that artists really had no other avenues for visibility or recognition. But because it excluded so many – from Courbet to Manet – artists’ needs were unmet, which ultimately prepared the ground for an alternative to overtake and surpass it. So, what can we take from that historic moment? What does that last major sea change in the art system tell us about what the future might hold for the market today?

HELMREICH: Yes, it’s interesting to look at when the Salon system collapsed in the 1910s and ’20s, right? World War I and then the Depression kind of crumbled that apparatus, and then in the interwar period, there was a lot of serious re-maneuvering and reshaping. So if I think of some of the big players in London that I’ve studied a lot, for example, in one case the space became a cinema. And some firms stayed on but really downscaled, and the ones that persisted were the ones that had really stable and strong relationships with artists, including artists who exhibited in multiple places and were able to maintain their visibility and networks in this way. So if we look at when that market downturned and reemerged again, it reemerged with very different and much smaller gallery models. The corporatization that happened at the end of the 19th century collapsed in on itself, and then the market was reborn again.

DEGEN: It’s interesting because we’re coming out of a period when it seemed inevitable that the market would move toward greater efficiency, consolidation, and growth. And yet, maybe not.

GLIMCHER: The monopoly and the duopoly are super stable in our society. You can be forgiven for looking at Gagosian and Hauser & Wirth and imagining a dualistic Sotheby’s-Christie’s future. I don’t know – it doesn’t sound like any fun to me. I think that the quirky, niche, intellectual actors now have a shot at consolidation. Instead of crushing everything into a few giant brands – as happened in the auction world and the talent-agency world – maybe consolidation goes another way. And families of brands do exist and enjoy economies of scale while also enjoying independence and all the diversity and weirdness that makes this interesting. That’s where I hope we’re headed.

Natasha Degen is professor and chair of Art Market Studies at the Fashion Institute of Technology, part of the State University of New York. She is the author of Merchants of Style: Art and Fashion After Warhol (Reaktion Books, 2023), editor of The Market (MIT Press, 2013), and has contributed to publications including The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Financial Times, Artforum, and Frieze.

Anne Helmreich is the director of the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution. Prior to her appointment, she was the associate director at the Getty Foundation and formerly the associate director of digital initiatives at the Getty Research Institute, both of the J. Paul Getty Trust. She has also served as a dean at TCU College of Fine Arts, senior program officer at the Getty Foundation, and associate professor of art history and director at Baker-Nord Center for the Humanities, Case Western Reserve University. Her current research focuses on the history of the art market and the productive intersection of the digital humanities and art history.

Marc Glimcher has served as CEO of Pace Gallery since 2011, during which time he has greatly expanded its international scope. His drive to enrich Pace’s contemporary program complements the gallery’s representation of prominent artist estates and advances the gallery’s mission to support the work of the leading artists of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Nicole Hackert studied art history and psychology in Mexico City, Cologne, and Berlin from 1988 to 1994. In 1994, she founded Contemporary Fine Arts in Berlin; since 2023, the gallery has also had a location in Basel.

Dirk Boll is a trained lawyer and art manager. He joined Christie’s in 1998. In 2022, he was appointed Deputy Chairman for 20th & 21st Century Art. Since 2009, he has published various books on the art markets, collecting, and museum development. His handbook Art and Its Market was published in 2024 (Hatje Cantz).

Image credits: 1. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, public domain; 2. public domain; 3. Courtesy Pace Gallery; 4. Alamy, photo Mike Goldwater; 5. public domain; 6. Peter Doig / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025, courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, photo Jochen Littkemann; 7. Alamy, photo John Angelillo; 8. Alamy, photo Nils Jorgensen.