Dada Goes To Washington Benjamin H. D. Buchloh On "Dada" At The National Gallery Of Art, Washington

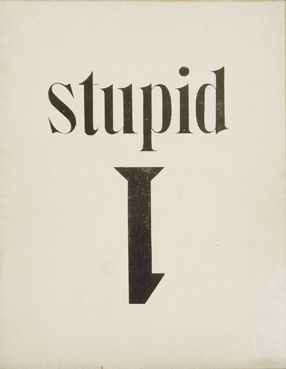

Undoubtedly, retrospective sentiment is the most un-dadaistic of emotions, and Max Ernst might have been right for once when stating that one should not try to glue together the fragments of the Dada grenade. Nevertheless, I will indulge for a moment in the reminiscence of having seen my first Dada retrospective as a highschool student in Düsseldorf in 1958, and compare my memories of that encounter with a second one, almost fifty years later, the extraordinarily careful and comprehensive exhibition organized by Leah Dickerman at the National Gallery in Washington (in collaboration with Laurent LeBon at the Centre Georges Pompidou where the exhibition was first shown in late 2005, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where it will be on view during the forthcoming summer). The latter institution had of course been the site of the two other major exhibitions of Dada, spaced thirty years apart, Alfred Barr’s "Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism" in 1936, and William Rubin’s "Dada and Surrealism", not only solidifying Barr’s depoliticizing spell in 1968 (e.g. John Heartfield was absent), but also fusing Dada’s legacies with the local practices of Pop. All four exhibitions together would offer a great quartet to study how the meanings of one of the most important revolutions in modern art, have been reconstructed as exhibitions according to the needs and limits of the historical contexts and institutions of reception. The 1958 exhibition in Germany reconstructed a segment of the twentieth century that was radically different from the one which West Germany was at that time still actively repressing. Dadaism in 1958 hailed across the borders of countries and decades, and imbued the present with a sense of cultural promise and political potential (temporarily and partially fulfilled in the moment of 1968). By contrast, the current exhibition’s immense scholarly apparatus and exhaustive documentation, paradoxically conveys a somewhat melancholic sense of closure. After all, from the present moment, all the more so from the supreme court site of Washington’s National Gallery, Dada’s politics, and its violent and vitriolic critiques of language, of representation, and of object relations, appear as decisively inaccessible, as phenomena from a different culture and distant past whose resuscitation is far from probable. What the current exhibition makes evident first of all is the fact that the Western world has never again achieved a comparable intensity of international solidarity and rebellion with artistic means. Dada was staged by extremely different subjects in various locations (and it is one of the many virtues of the current exhibition to emphasize these geo-political and cultural differences). Yet at least one common target can be identified : the universal critique of bourgeois subjectivity and all forms of its cultural representations (poetry, painting, professionalism, private property). The strategies of that critique ranged from a post Expressionist mystic pacifism (e.g. Hugo Ball), to an ostentatiously cynical anti-aesthetic (e.g. Francis Picabia), from the Mallarméan critique of journalistic media culture as a daily destruction of the poetics of language (e.g. Tristan Tzara) to the denial of painting’s representational functions by an embrace of photographic fragmentation (e.g. Hannah Hoech). But Dada also subverted the subject’s heterosexist definition, foregrounding the emerging androgynous or polymorph perverse subject of an Anti Oedipal future (e.g. Marcel Duchamp). Or Dada would oppose the bourgeois’ voracious demand for unlimited power and control by mobilizing weak thought and the myths of an inalienable self or an unalienated childhood, performing alternate subjectivities that derailed the dominant model of the self as the agent of private property and domination. These strategies appear now most stunningly in the exhibition’s exquisite display of the long underrated sculptural work of Sophie Taeuber, and equally in her abstract needlepoint work, as much as in the duo collages that she produced with Jean Arp. And their forceful utopian negations of any further validity of bourgeois subjectivity are no less evident in the exhibition’s exceptional display of Kurt Schwitters’s collages. These incantations of the forgotten and the forlorn, the obsolete and the dysfunctional seem to promise the rise of a new subjectivity from the ashes of the empires of consumption, One explanation for Dadaism’s frenetic search for alternatives to the bourgeois is to be found in its lack of a proleatarian countersubject, a model that had obviously laid the foundation of the Russian and Soviet avantgardes working in the same historical, but in radically different social spaces. And another, equally fascinating absence in Dada is of course its refusal (or historical inability) to proclaim the newly found access to the subject’s unconscious as a utopian alternative, an ideologem that Dada’s Surrealist sequels would universally embrace. The most difficult theoretical and methodological problem posed by Dada remains the question of historical causality: whether the annihilation of traditional meaning was primarily propelled by the cataclysmic collapse of bourgeois Imperialist culture, culminating in WW I, or whether the destruction of conventions of meaning and representation should rather be traced to the semiotic revolution triggered by the rise of structural linguistics. For example, which factor should be given primary explanatory power for what Briony Fer has recently identified brilliantly as Dada’s "psycho-typography"? If we argue that Dada followed Futurism’s mimetic simulation of language as a vortex collecting and dispersing the reflexes of warfare, we might end up with rather precise interpretations of what was specific to German Dada but would totally fail to understand the work of Marcel Duchamp, the greatest Dadaist of all. Or if we argue that the processes of bodily amputation resulting from the war were the primary cause of textual and iconic fragmentation, as proposed by Brigid Doherty’s essays in the catalogue, we find ourselves returning to the very geo-political limitations that Dada had ceaselessly aimed to transcend. Worse yet, this interpretive approach suffers from the paradox that it reestablishes a model of referential meaning and conventional representation in the very center of an artistic project whose primordial goal had been precisely to dislodge any form of a centered intentional subjectivity, and any referential causality in the relationship between signifier and signified. One of the strangest conditions of Dada’s history is not only the brevity of the adventure (five years, at the most, in most locations, be it Zürich, New York, Berlin or Paris), and the sudden abortion of the Dada revolution, but the immediate re-conversion of some of its members to culture. After all, under the spell of their discovery of de Chirico’s "persistence of memory", quite a few dadaists returned to painting after 1921, albeit with different motivations and different results. Thus one wants to ask George Grosz and Christian Schad, just as much as Francis Picabia and Max Ernst, why they made Louis Aragon’s fundamental manifesto "La peinture au défi", celebrating the victory of collage and photomontage over painting, an invalid statement by the time of its publication in 1930. In the case of Grosz and Schad, the relapse would be called Neue Sachlichkeit, and its melancholic currents would eventually prove deadly for both of them. In the case of Picabia, Man Ray and Ernst, the return to painting would become part of a larger cultural diversion, away from the crisis of the subject and the collective to an aestheticization of the unconscious, and its new culture, triumphantly formulated by André Breton’s "Le Surréalisme et la peinture" in 1928. But the hardest task posed by this amazing exhibition is of course to judge those contemporary practices that claim Dada in one way or the other as their pedigree and predecessors. And it is even harder to explain the differences in resistance that distinguished the Dada masters of weak thought, from the neurasthenic victims of opportunistic assimilation like Jeff Koons or Takashi Murakami in the present. But it is equally hard to fathom what type of public would have provoked the Dada rebellions, and what type of public in the present would forfeit them forever, by repressive tolerance as much as by a fatal failure of psychic and intellectual energy to even consider that the historical registers of resistance and opposition continue to be the integral elements of any aesthetic project worth its name.

"Dada", National Gallery of Art, Washington, February 19 to May 14, 2006