Holy Terror On Merlin Carpenter at Simon Lee Gallery, London by Mike Sperlinger

“In the rich man’s house”, Diogenes of Sinope is reputed to have said, “there is no place to spit but in his face.” History’s original Cynic might have found himself at home at the opening of “The Opening” at Simon Lee Gallery, confronted with the sight of Merlin Carpenter daubing a blank canvas with the legend: “Simon Lee utter swine”.

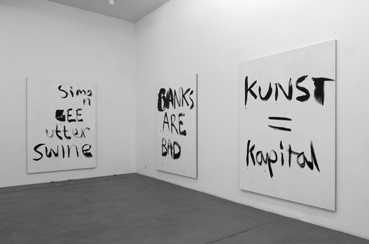

The exhibition is the fifth in a series of shows by Carpenter in which the paintings are produced during the private view – although in the press release, Carpenter leaves open the hypothetical possibility that the canvases might simply remain blank (“If the works are painted …”). Carpenter left it late on this occasion, allowing some of the audience to drift away and the ice-sculpted platter for finger food to melt a little, before painting the eleven canvases in the course of a couple of minutes, trailing a cloud of sweaty spectators. Most of the resulting paintings took the form of slogans – alongside the swinish assessment of his host, others read “CUNTS”, “Bad BEUYS”, “KUNST”, “STOP ART”, “BANKS ARE BAD”, “KUNST?=? Kapital”, “Beuys BADBOI” and “DESTROY NEO LIBERAL”. The only exceptions were a delicate Ab-Ex splash and a Beuys-like black cross. From accounts of previous instalments in the series it appears Carpenter’s work has entered a more classical phase – none of the paintings ran onto the wall space, as was the case at Overduin and Kite in Los Angeles last year, nor was there the coup of painting them from a moving car, as at the Christian Nagel-organised Mercedes Benz showroom event in Berlin in May 2008.

Carpenter’s current cycle is exemplary in its reductiveness: he is an outrider of idealistic cynicism, the lone horseman of an adolescent apocalypse (the press release talks of the current “depression” leading towards “starvation and Mad Max”). Cynicism is the very real stake to which Carpenter has tied himself and, with commendable crassness, his work marks out the limits of self-criticism in the art world, corroding the difference between being undeceived and being disillusioned. Peter Sloterdijk defined distinctively modern cynicism as “enlightened false consciousness”, a kind of ironic impotence. How we judge an art of cynicism might depend whether we stress the irony or the impotence. Even if we wish to recuperate cynicism, however, the irreducible risk remains: like all forms of irony it constantly trumps critical judgment by retreating to another level of reflexivity – the commercial exploitation of these paintings, for example, becomes a self-conscious part of their anti-heroic posture. In the press release Carpenter writes that if capitalism is able to repurpose all criticism to improve itself, “better to go on art strike, wander into your own show, outraged ... ready to vandalise and destroy”. But of course, “The Opening” is no “art strike” – the putative possibility of non-performance is a tease. And what is being destroyed? The pristine canvases? Carpenter’s practice and/or career? Or, in full apocalyptic mode, the possibility of art per se? Is Carpenter a Samson, bringing down the temple bathetically on all our heads?

Another way to understand “The Opening” is as an act of withholding, like a parody of those placeholder pieces Adrian Piper made in the 1970s which declared that “the work originally intended for this space has been withdrawn” in the face of general conditions of “repression, racism, hypo-crisy and murder”. [1] The show’s graffiti-style slogans solicit our embarrassment, however, rather than our solidarity. In his recent writing, Carpenter suggests a strategic scrupulousness verging on the paranoic in the face of possible recuperation; if capitalists are on standby to monetise even critical insights then – like Diogenes, who famously defaced the currency – he proposes dealing in bad coin: “Instead of critiquing market formations in advanced capitalism and feeding this data as information to the art world, better to feed the art world to the art world.” [2] Beuys’s utopian creativity is reconstituted only for the purposes of historical gavage, on which we are invited to gag. As if haunted by the spectre of Lee Lozano, the painter whose intransigent withdrawal from the art world in the 1970s only fed the speculative hunger for her work when it was recently “rediscovered”, Carpenter tries to head-off cooption by offering, instead of protest, only a perfunctory and ironic pantomime of protest’s impossibility. In this, he perhaps goes beyond cynicism and into a kind of literal nihilism – something akin to the late Keith Arnatt’s 1970 piece “Is It Possible for Me to Do Nothing as My Contribution to This Exhibition” (1970). Arnatt’s work was a witty, genteel text parsing the paradoxes of proffering nothing: any “contribution”, however nugatory, is already a something. Carpenter’s “Opening” series, on the other hand, is a vicious circle in which satire performs its own failure and (presumably) profits from it.

“The Opening” paints its audience into a corner. Its tautologies mean response is pre-programmed and by engaging with it at all – whether as audience, critics or chattering classes – we enter a fatal complicity in which we can only (moralistically) denounce or (cynically) applaud the gesture. Any insight comes courtesy of the absurdity of this dilemma, which is authentic, rather than the terms of the dilemma itself. There are, of course, other aspects of complicity. Carpenter has written: “If you criticised your friends you would be implicated. Self-criticism then maybe starts with your friends.”[3]_ Merlin is a friend, and I would suggest that “The Opening” represents the wrong cul-de-sac. There is undoubtedly a virtuoso perversity in holding to the terms of a complex critique, as evinced in Carpenter’s writing, by exhibiting anti-market commodities in a Mayfair gallery. But I would suggest that “bad coin” practices ultimately rely on a kind of occult vanguard optimism, a belief in the good coin which is withheld, coupled with an overestimation of the importance of intention.

Carpenter remains a holy terror to an art world which prefers the more innocent cynicism of careers based on Kunsthalle-funded critique: a conspiracy of good faith. “The Opening”, by contrast, offers with unsettling directness the impossibility of deciding on whom the joke is, and for this we may be grateful. There is something preferable in bad jokes, perhaps because they remind us how priggish all good jokes are. In this case, however, even if it is not clear who has the last laugh, there is no doubting that all this laughter is very late.

Merlin Carpenter, “The Opening”, Simon Lee Gallery, London, April 1 – April 25, 2009.