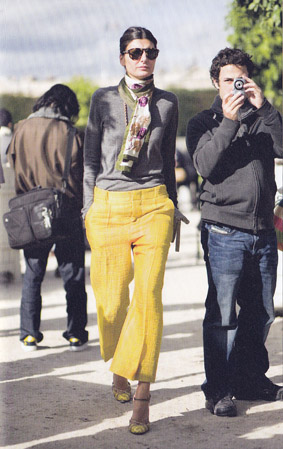

Modeblogszene aus „The Sartorialist“, Paris, Dezember 2008

Modeblogszene aus „The Sartorialist“, Paris, Dezember 2008

Street-style blogs are considered must-reads for all those who want to be sure they’re up to date on the latest fashions. They promise glimpses of insight into what is being worn on the streets of the metropolises of this world, what to combine with what and how. Beyond wearing the creations of designers, the aim is to fashion one’s own style: that is what matters in the new spirit of capitalism, which rewards individuality that has commercial surplus value.

With their glance at the “street”, these blogs are thus considered autonomous authorities that continually produce new and, it seems, authentic fashion imagery. But do “Jak&Jil” and “styleclicker” really foster a democratization of the world of fashion, as many believe because of their alleged independence of the global fashion industry and its traditional channels of communication? Or are the pictures of fashion these blogs paint likewise subject to ideals about beauty, about the body, about Fashion?

The New Favorites of the Fashion World

The history of fashion has repeatedly seen demands for greater participation and broader inclusion. The last great revolution of this kind was the emergence of prêt-à-porter in the late 1950s and 1960s, when designers like Pierre Cardin and André Courrèges declared the haute couture production model to be obsolete and demanded top quality fashion for all, not simply for ten thousand private clients who could afford to buy unique custom-made garments.

Today we again see a historical constellation in which the aristocratic model of fashion is put into question. By embedding fashion in (seemingly) everyday urban contexts and using people on the street as models, street style blogs have again raised the issue of the democratization of fashion. However, while street style blogs may have brought about concrete changes on aesthetic and thematic levels, their democratizing effect is a strictly relative one.

Street style photographers like Yvan Rodic and his New York colleague Scott Schuman, author of the blog The Sartorialist , are the new stars of the fashion scene. Rodic, the man behind the famous street style blog facehunter gives this description of his approach to fashion photography: “I’ve never understood why fashion editors waste so much money and time schlepping expressionless models halfway round the world for a single photo shoot. Their lives would be a whole lot simpler if they worked like me: just go to some exciting city, find a stylish natural beauty who lives round the corner, go to the nearest playground, pose them on the slide, give the kids some candy to go away, then press the shutter. Five minutes later it’s done, and you can go chill out on a café terrace”. The work of photography is here depicted as a kind of leisure activity, casual and random. Also striking is the key role played by the city in this mystifying scenario. Sidewalks, street corners, building facades, inner courtyards, back alleys and parks all serve as preferred locations for Rodic’s staging of passers-by who strike him with their extraordinary sense of style. The resulting photos appear on his blog, where they are commented on by fashion enthusiasts from around the globe.

There is no longer any question that the Internet, above all Web 2.0, has affected fashion more than almost any other area of cultural production. Since March of this year, when American Vogue organized a photo shoot with the ten (in their view) most important fashion bloggers, no one – not even the detached Anna Wintour – can deny the emergence of blogs as a fashion medium in their own right, existing alongside traditional print vehicles. Street style blogs document what the “hip crowd” is wearing in New York, London, Paris, Berlin or Helsinki: these images of beautiful and well dressed people in their everyday urban environment are well on their way to being the defining fashion images of a whole decade. How did this happen?

Street style photography as a genre of -fashion photography

Until the mid-1990s, street style (or street fashion) referred to a specific form of everyday fashion, inspired by subcultures. The first use of street style as a fashion category came in August 1980, in the first edition of the British independent magazine i-D . The magazine’s “straight-up” section showed images of punks and new wave kids who had been discovered by photographers on the streets of the metropolis. These semi-documentary images – full-length figures (hence the name “straight-up”), shot in natural light, against a simple backdrop of walls or house fronts – stood in stark contrast to conventional studio photography in the glossy magazines. The kids in the pictures were both models and (their own) stylists (making this role redundant). The makers of i-D criticized the elitist self-image of traditional fashion magazines; with “straight up”, they created a model which broke with all previous conventions, standing in opposition to these magazines’ highly staged fashion spreads. Alongside i-D, magazines like The Face, Dazed & Confused and Street contributed substantially to the creation of particular street style aesthetic. However, in the course of the last ten years, gradual commercialization has meant the loss of street style photography’s original subversive, anti-high-fashion attitude, gaining popularity as a genre within mainstream fashion journalism. About ten years ago, magazines like British Elle and Vogue and Jalouse in France began to produce their own street style sections, modeled on i-D.

The genre’s real boom came with the Internet. The initial success of street style blogs was partly because blog addresses were at first only exchanged online. For a long time they remained a kind of insider tip for those in the know. Adding to their fascination was the way street style blogs extended the fashion map beyond Paris, New York, Milan and London, bringing in other cities, until now blank spaces. Since 2005, for example, one of the oldest street style blogs, hel-looks.com , has shown a selection of looks from the streets of the Finnish capital Helsinki. But the best-known and most successful street style blogs do not limit themselves to a single city: their authors travel constantly, documenting the styles of a wide variety of locations, from Jakarta to Buenos Aires. In this way they correspond to the imperative to mobility and networking identified by Boltanski and Chiapello as a fundamental characteristic of modern network capitalism. However, whether in their blogs’ mini-bios or through self-narrativization in interviews, street style bloggers present themselves as romantic flaneurs, deliberately disguising the amount of work that goes into successfully running a blog. In spite of this pose, street style photographers are actually under distinct pressure to expand their competence profile. They must be constantly in touch with what is happening, can never miss an important event, should always be first to track down the latest trends – they have to be, in a sense, photographer, stylist, editor and trend-scout all in one.

The graphic design of street style blogs is relatively homogenous: simple and clearly structured layouts dominate, with the photographs in the centre. The accompanying texts are mostly limited to quick descriptions of the outfits or short accounts of how the photographer came to make the image. An important element of sites like styleclicker , Jak & Jil and Stil in Berlin is the commentary function, which allows users to discuss the images. Photos on the most popular street style blogs, as with the aforementioned The Sartorialist, usually draw hundreds of commentators, who analyze the outfits down the smallest detail. In general, effusive praise is the rule, critique far rarer. Community contributions mostly focus on the color, texture and quality of shoe laces, seam stitching, hand-warmers or pocket handkerchiefs, and much less on the overall appearance of the person photographed. There are frequent descriptions of pop-cultural or literary associations which a garment or color combination caused in the viewer. In this way, street style blogs not only produce new fashion images, they produce narratives, moods and explanations to go with them.

Democratization – the illusion of inclusion

Today, street style refers to any clothing photographed on the street using non-professional models, from light leisure clothes to elaborate party outfits and the classic business look. The photographers themselves emphasize that the style is not limited to a particular age group or milieu. Authors of street style blogs profess to show fashion “from below”, free from the dictates of designers and fashion magazines, created by the people themselves. It is repeatedly claimed that street style blogs are driving a democratization of fashion, as ordinary people become models and act as their own stylists. They thus question the top-down distribution model of fashion innovation and appear to confirm the anthropologist Ted Polhemus’s “bubble-up” hypothesis, which suggests that new trends are not invented by designers but discovered by trend-scouts in the hip neighborhoods of London and other cities. But above all, it is claimed that street style blogs are bringing about a democratization of fashion, thanks to their aesthetic of the everyday. What techniques do street style images use to suggest this supposed everyday quality?

The images’ settings are quite different to the standard fashion magazine photo sequences. The protagonists appear as “normal” people encountered by the street style photographer on one of his passages through the city. Everyday chic is the main thing: it is not at all about perfection and little flaws are left visible. The impression of authenticity is accentuated by the sense that these people are going about their daily business: lit cigarettes, paper coffee cups, newspapers under the arm, bicycles and shopping bags all stay in the picture, more evidence for the authenticity of the individual shown. Fashion is made to seem like a basic element of their lives, belonging to everyday normality like the newspaper or a quick coffee. Fashion happens en passant, it is here presented as a self-evident attribute of a cosmopolitan person. In this way, the images claim proximity with the life world of the reader, who is left with the impression that they too could be discovered by a street style photographer, if they just happened to be in the right place at the right time in the right clothes.

However, this mode of representation – which gives the impression of a personal, subjective selection of outfits and people – distracts from the obvious fact that, contrary to their claims, street style bloggers do not photograph everyday looks or only feature anonymous people. For example, before his second career as a blogger Scott Schuman worked for many years in the fashion industry. No wonder that – as can be gathered from Schuman’s captions and his readers’ comments – many of the people he portrays work in the fashion business and so put particular emphasis on their appearance (or ought to). The authenticity claimed by the photos is revealed as a construction. The distinction between models and “normal people” blurs, not because the blogs set new criteria for beauty and fashion consciousness, but because they photograph people who have thoroughly and convincingly incorporated existing criteria.

There have already been attempts online to dissolve the myth of fashion blogs’ exclusivity. Thus “Our Step-by-step Guide to getting shot by The Sartorialist” , an infographic in the online magazine Refinery29, illustrates an imagined version of Schuman’s process of perception. Men, apparently, have a good chance of being photographed by Schuman if they are “old, rich and European”. If they also accessorize with a loosely-draped cashmere scarf or a cigarette, then a Sartorialist appearance is pretty much in the bag. For women, the most straightforward way to appear in this sought-after blog is to be either Kate Lanphear or Giovanna Battaglia, two young and beautiful fashion editors. Otherwise, for women to be noticed by Schuman, they should at least be “model-pretty”, preferably in a city playing host to a fashion week.

These attempts to identify a pattern to blogs’ selection of protagonists could of course be seen as a sign of their significance as a mode of fashion communication and, more generally, of the canonization of street style. Like photospreads in fashion magazines, street style blogs have become reference points, consulted by people who want to be informed about the most up-to-date looks. Indeed they may work far better than standard photo sequences, because of their apparent proximity to the life world of the consumer. The images show fashion in casual, easily consumable form. Street style blogs, you might say, are the off-the-rack products of fashion photography, showing fashion on “real people” in “everyday situations”. When professional photo shoots abstract fashion from reality, they give it the character of a fiction. As Roland Barthes noted: “In fashion photography, the world habitually is turned into decoration, background, scene: in short, theatre.” By contrast, the location in the street style blogs is a real place, with the city no longer just scenery in the photos, but a protagonist in its own right. Whether Milan, Sao Paolo, Paris, Melbourne or London, the city is seen as an important factor contributing to the formation of a specific style. As Yvan Rodic has put it in his recently published photo book “Facehunter”: “For us, the city is not an asphalt jungle, it is more like a good girlfriend who we like to hang out with”.

The emphasis on geographically-based differences is driven in particular by blog commentators, often by referring back to old fashion clichés. A striped top and red lipstick is still seen in terms of “Parisian chic”, even if – paradoxically – the photo is not taken in Paris but in Stockholm. On the one hand, thus, there is a construction and perpetuation of regional and national style-identities, on the other, simultaneous emphasis on an idea of style, transcending geographical borders and social differences.

On the Relation of Style and Fashion

It is also striking how little street style blogs talk about fashion – they are far more likely to mention style. Among the global fashion-conscious hip crowd, an unmistakable personal style – identifiable by a person’s clothes, but also their haircut and body language – is viewed as something like a basic survival competence. Social media platforms like Facebook, Myspace and Twitter are stages for the modern performance of the self: here the daily work of emphasizing individuality and uniqueness takes place. Street style blogs document this striving for individuality, especially in their celebration of attention to detail and nuance – the things which reveal whether a person has style, or does not.

Where does the difference lie between fashion and style? The sociologist René König understood style to be a fashion which time had hardened into a constant. In 1967, he wrote: “It could even be suggested that all styles began as fashions, then after more or less extensive experiments they develop – or ‘crystallize’ – into a lasting form”. König suggests that style is in a certain sense a stable form, emerging from fashion and independent from individual trends. In contrast, Dick Hebdige’s study “Subculture: The Meaning of Style” introduced into fashion discourse a new, semiotic understanding of style. In the course of his investigation into youth subcultures among the British working class, he showed that these subcultures turned clothes, musical tastes and leisure habits – in other words, their style – into the bearers of new meaning. Hebdige identified a number of techniques – mixing, sampling and bricolage – used by Mods, Teddyboys, Skinheads, Punks and Rastafaris to grant new meanings to available cultural practices and symbols. Style here is understood to mean something above mere fashion: it is a program structuring a whole personality. Precisely the subcultures which Hebdige described in this book were, as mentioned above, the sources of inspiration for i-D’s first street style images.

The only identifiable driver of modern street style is a highly intensified individuality, expressed in an obsessive love of fashion detail. What counts is creating the right mix of colors, patterns, materials and labels, what matters is knowing how to combine vintage clothes with designer pieces and bargains from chains like H & M. This is the red thread that runs through the fashion of the street style blogs, making plausible König’s definition of style as sedimented aesthetics, abstracted from fashion’s day-to-day events. Details are particularly important at the edges of outfits – flashes of color spilling out at the feet or wrists of an otherwise monochrome look, or scuffed places on the collar of a formal jacket. Seldom in these pictures will one see really shrill, provocative or extreme outfits, but the opposite – the basic everyday clothes actually worn by the broad mass on the street – is just as rare. What is really popular with street style photographers are unprecedented combinations and conscious breaks with style. Standard beauty ideals, as dictated by the fashion industry, are largely speaking reproduced, particularly as they concern body image. There are, for example, barely any photos of overweight or physically handicapped people – the appearance of the majority of those represented corresponds to stereotypical ideas of beauty. The aim of the fashion-conscious cosmopolitan still appears to be to catch the eye, but only at a second glance. The condition aimed for: to have “style”, to exhibit it and to be recognized for it. Whoever has style is something special because of their uniqueness and individuality, thereby raising themselves above the uniform, “unstylish” masses. And the final consecration of any personal style is to be pictured on a well-known street style blog. Particularly within the fashion scene, an appearance here is the ultimate recognition, a kind of knighthood.

Street Style Blogs as documents of fashion’s pluralization

The emerging power of street style blogs has left its mark on fashion’s communications system. The hype around fashion blogs has led, for example, to fashion magazines improving and extending their online presence. Having recognized the centrality of the medium for fashion, they thus perceive blogs as competition. To maintain their power of definition within the fashion world, many well-known fashion magazines have adopted a strategy of collaboration with well-known street style bloggers, both in print and online. Scott Schuman now takes photographs for GQ and style.com (the website of American Vogue), while his girlfriend, the French blogger Garance Doré, has a section in the online version of French Vogue in addition to her own blog.

However, the influence of street style blogs on fashion innovation is – at least in my opinion and in spite of the claims of those involved – not clearly established. It seems improbable that street style blogs do in fact publish tomorrow’s trends today. According to the sociologist Frédéric Monneyron, there is still need for designers’ “mediating function”, which converts street innovations into mass-producible versions. In any case, with the consistent growth of the so-called fast fashion chains like H & M, Zara, Mango, Topshop and Target, change in fashions has accelerated massively, making any reconstruction of the origins of particular trends increasingly obsolete. With their extremely short production cycles, fast fashion chains can supply their stores with new products on a monthly basis (unlike the quarterly or half-yearly models of the prêt-à-porter labels), allowing them to react to new trends in a very short time. It can no longer be established with any precision whether trends first appeared on a street style blog, a celebrity or on the catwalk in Paris.

Ultimately, street style blogs are a further proof of contemporary fashion’s pluralism at the level of content, with dominant tendencies difficult to identify. As the philosopher Gilles Lipovetsky puts it: “Fashion’s new configuration is open, uncompartmentalized, and nondirective”. The decisive contribution of the street style photographers lies in directing the attention of the fashion public towards this plurality of personal styles. Nonetheless they also remind us that exclusivity is and remains the central characteristic of fashion, which ultimately lives by its capacity to make distinctions.

(translation: Clemens Krümmel)

Notes

Modeblogszene aus „The Sartorialist“, Paris, Dezember 2008

Modeblogszene aus „The Sartorialist“, Paris, Dezember 2008