Playing House

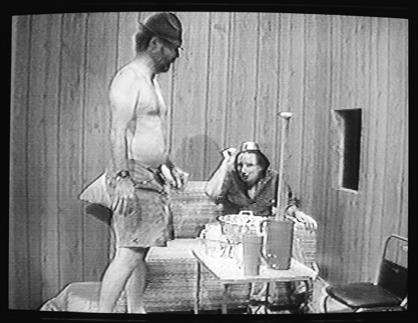

Paul McCarthy, “Family Tyranny (Modeling and Molding) and Cultural Soup by Paul McCarthy (with Mike Kelley)”, 1987, Film Still

Paul McCarthy, “Family Tyranny (Modeling and Molding) and Cultural Soup by Paul McCarthy (with Mike Kelley)”, 1987, Film Still

Like all relationships, collaborations entail some kind of interpersonal dynamic. When Mike Kelley worked with other artists – especially in the medium of film – he often embodied a role that involved subordinating himself to them as either a child or a pupil.

From such a position, Kelley was able not only to reflect on themes of adolescence and education, but also, more abstractly, on the position of inferiority and subservience. Throughout the artist’s work, he found the potential for power and critique in relation to sources of dominance; after all, the performance itself – the concrete words and actions – serve to represent an experience in a way that viewers can perceive.

This past April’s daylong screening “Mike Kelley: Video Tribute”, at Electronic Arts Intermix in New York, included videos spanning a 28-year period and provided an overview of Kelley’s prolific life, which had ended earlier that year. When I arrived in the late morning, “A Voyage of Growth and Discovery” (2011), a collaboration between Kelley and artist Mike Smith, was already underway. I had seen an iteration of it at SculptureCenter in New York in 2009, so I did not stay for the full screening. I returned an hour later for “Blind Country”, Ericka Beckman’s 1989 video with “script and performance” by Kelley. This was immediately followed by “Family Tyranny (Modeling and Molding)”, the 1987 video by Paul McCarthy also starring Kelley.

Beckman and McCarthy’s videos make a perfect pair. In both, Kelley is variously cast as a child, a son, and a confused and vulnerable student who must be taught a lesson. Kelley’s contribution to “Blind Country” includes a scrolling script that uses mnemonic devices and poses questions that put the viewer in an active role, like that of an audience member viewing one of Kelley’s early performance works. In a recent conversation over the phone, Beckman relayed to me that her collaboration was rooted in a friendship that generated nearly a decade’s worth of conversations and letters that revisited and revised different scripts initially intended for a live audience. Kelley later approached Beckman to make a video that used his adaptation of H. G. Wells’s “The Country of the Blind” (1904) as its foundation. Beckman further explained that Kelley needed to distance himself from the physical proximity of his audience, and video provided the perfect medium to do so. Early on in “Blind Country”, what appears to be a pool cue points toward Kelley’s crotch, and his voiceover recites the following: My little piece of talent. Have you learned the lesson of what goes into what? […] Strive to refill the quickly emptying sack. Time is short though. Santa has a full year to labor so that his sack may be restocked. Mommy’s labor needs but nine months. And daddy’s time’s a short time that his sack’s replenished. Kelley’s face appears center screen as he asks: Daddy’s little man, aren’t you?

A minute later, Aura Rosenberg appears as a maternal guide to Kelley’s character. They are not mother and son. She is referred to as “señorita” and is costumed in a Mexican peasant dress. Her patience quickly fades as Kelley persists in asking: Does this go here? – while inserting various objects into parts of his close-to-naked body. Rosenberg’s character later reappears, but her role has changed. She is dressed in lingerie and treats Kelley’s character like a dog, requiring him to fetch her slipper that she then uses as a loofah sponge to wash her body. The themes of gender, sex, power, and instruction enacted throughout “Blind Country” are perfectly bookended by the father-son relationship found in the video “Family Tyranny”.

We hear Paul McCarthy, cast as a basement-dwelling father, as the video begins: He’s been a very bad boy. We don’t see him in full, only his chest and arms, as he forces a funnel into the “mouth” of a coconut-sized ball of Styrofoam. The force of wedging the funnel into the cartoon orifice is made evident by a cracking sound. McCarthy’s character provides the following instruction: You can all do this at home. Try to do this at home. My daddy made me do this. He did this to me. You can do this to your sons, too […] Once you teach this to your son he’ll be able to pass it on to his son. OK? What you have to do is emotionally give this to him. Kelley enters. (Later, in a written statement concerning the video, Kelley remembered that when he asked McCarthy what he wanted him to do, the latter replied, “I’m the father and you’re the son.” [1] ) As the father, McCarthy asks, I told you how my dad did it, right? To which Kelley, fully embodying the role of terrified son, lets out a hound dog yelp. McCarthy responds with paternal precision: I’m gonna do the same to thing to you. We return to the previously seen Styrofoam ball and funnel; through the latter, the former is being force-fed a white plaster-like liquid from a beer mug. McCarthy sings: Daddy come home from work again, daddy come home from work. His character resumes his instructions as he forces his fist into the funnel, causing the liquid to pour back out of the Styrofoam’s hole: Let em feel it. Let em get used to it. Do it slowly […] They’ll remember it. Don’t worry about that. They’ll remember it […] They’ll use it. This scene fades into one depicting McCarthy-as-father, shirtless, inserting the end of a baseball bat into a water pitcher balanced on a small table, under which a bundled Kelley-as-son cowers. The latter begins to moan to the rhythm of the bat’s thump and lifts the table, causing the pitcher’s white liquid to splash and spill. McCarthy, as dad, consoles him: There he goes. There he goes. I knew you had it in ya. Kelley emerges and disrobes: Time to go to school, dad.

It’s fitting that, in “Family Tyranny”, Kelley plays son to Paul McCarthy, an artist whom he championed and later collaborated with on longer and larger co-authored productions. They shared an interest in the economy of durational performance, using their own bodies and language to work with the familiar – as it derived both from the home and from popular culture – to unsettle and elicit “maximum affect from minimal means.” [2] Although both of their financial means of production dramatically increased, the following comment by Kelley could also be applied to his own most elaborate later work: “I suppose you could say that Paul is an Automatist but the work is grounded not in Jungian Archetypes but rather in everyday social conventions. His version of the primal [is] the one found in store-bought Halloween masks, and embodied in plastic dolls.” [3] About a third of the way through “Blind Country”, Kelley appears, dressed as a schoolboy, surrounded by children feverishly consuming candy in an elementary-school classroom. His manner and voice make it seem as if he is the same boy as in “Family Tyranny”, having now left the wood-paneled basement. When the teacher demonstrates how to fill a void by fitting brightly-colored geometric forms into corresponding frames, the class erupts in laughter. Kelley sits in the back of the room, covering his face as if he has a bloody nose or is holding back vomit. The teacher aggressively asks: What’s that you’ve got in your mouth? Kelley weakly responds: Nothing. The following exchange ensues:

Teacher: Perhaps you’d like to spit out what you’ve got on this mirror?

Kelley: No thank you.

Teacher: Perhaps you’d like to spit and shit and piss on this mirror, in front of

everyone.

Kelley: I don’t wanna.

Teacher: I think we’d all like to see what it is you got and what you’ve been

keeping to yourself.

The video then cuts to Kelley’s character, now dressed in a suit, a professor in a lecture hall. All of the students are Kelley doubles donned with blonde wigs and prosthetic pig snouts. Is he passing on what he has learned to his “sons”, as per McCarthy’s fatherly teachings in “Family Tyranny”? These lookalikes, like the children in the previous scene of “Blind Country”, are aroused not by sugar, but by the smells and bodily forms of their adult instructor. Simple, animated shapes of a square, triangle, and circle, in primary colors, demarcate and adorn Kelley’s butt, crotch, and armpit, as his students seem to be getting high off their aroma.

In his paper “Cross Gender/Cross Genre” Kelley wrote of his childhood and generational context: “I was mediated, I was part of the TV generation, I was ‘Pop’.” [4] This quote, from a 1999 talk given in Graz, Austria, is a succinct thread connecting Kelley’s early performance work to these early video collaborations and also to his later, highly mediated works, including “Day is Done” (2005–2006). The sense of intimacy that Kelley created with his audience seems to have been contingent on and filtered through the physical proximity of a TV, as found in a home.

As we do with Mike Smith’s Baby Ikki in “A Voyage of Growth and Discovery”, which features the character’s exploration of the outlandish creations and corresponding participants found in the desert grounds of the Burning Man Festival, we empathize with the vulnerable child played by Kelley and engage him, even if we know he’s a grown man performing a part; the costuming didn’t hide his post-punk hair and acne-scarred face. The complexity of his adult body, with all of its odors and desires, cannot be shelved as we watch him take on the role of son and reprimanded child.

Kelley’s performances led me to recall the arrest of Paul Reubens in 1991 for indecent exposure at a porn theater in Sarasota, Florida, which led to his giving up the role of Pee-wee Herman. Wikipedia says it best: “The arrest set off a chain reaction of national media attention that changed the general public’s view of Reubens and Pee-wee.” And last year’s case of Kevin Clash, the voice of Elmo on “Sesame Street”, who got embroiled in a sex scandal with younger men that generated the memorable New York Post headline “Nookie Monster” on November 12, 2012.

To segue from one puppet to another, here’s an excerpt from John Miller’s obituary of Kelley in this magazine’s March 2012 issue, where he quoted an interview of Kelley’s from 1991: “The most frightening […] thing I can remember from my childhood was a puppet show on a children’s TV program about a puppet in one of these little prosceniums who was supposed to be on an endless stairway and falls off into nothingness. […] For years that has been my ideal. If I could make something that moving, that could have you frightened for the rest of your life and all it was a piece of clay that falls off a piece of cardboard. […] That so much emotion could be invested in this piece of shit – that’s amazing.” [5] Kelley’s roles in “Blind Country” and “Family Tyranny” were not padded by elaborate production. At the root is Kelley, the performer, who returns us psychically to the proscenium of our youth, with its various uncertainties, fears, and limitations – perhaps to help us exorcise ourselves of it all.

Notes

| [1] | Mike Kelley, “Family Tyranny and Cultural Soup” [1987], in: same, Minor Histories: Statements, Conversations, Proposals, ed. by John C. Welchman, Cambridge, Mass./London 2004, p. 194; also quoted at the EAI website online at: http://www.eai.org/title.htm?id=1297. |

| [2] | John Miller, “In Memoriam”, in: Texte zur Kunst, 85, 2012, pp. 245–247; p. 246. |

| [3] | Kelley quoted on the EAI website. |

| [4] | Kelley presented this talk in conjunction with the steirischer herbst exhibition/festival. Mike Kelley, “Cross-Gender/Cross-Genre” [1999], in: same, Foul Perfection. Essays and criticism, ed. by John C. Welchman, Cambridge, Mass./London 2003, pp. 100–12; p. 102. |

| [5] | John Miller, “In Memoriam”, op. cit., p. 246. |