Exhibitionist Architecture By Beatriz Colomina

Dan Graham, „Inspired by Moon Window“, 2003

It is curious to me that both essays privilege Minimalism to the exclusion of artists such as Gordon Matta-Clark and Dan Graham, who from the mid-1970s were experimenting more directly with the medium of architecture, tweaking the techniques of the field. Matta-Clark studied architecture at Cornell under Colin Rowe, and Graham knows more about the history of architecture and has a better library than most architects. Both were trying to break away from galleries and museums and did so by working with buildings.

It is also symptomatic that it was precisely during the late 1970s and early 1980s that architecture entered the museum and gallery system. In 1978 Max Protetch, who had been exhibiting Minimalist and Conceptual artists; but also Andy Warhol, early performances of Dan Graham, Vito Acconci, and others, moved his gallery from Washington, D. C. to New York and started to specialize in architectural drawings. In 1980 Leo Castelli mounted the exhibition “Houses for Sale”, in which an international group of eight architects were invited to put their visions of the modern house on “sale.” The catalogue clarifies that “drawings may be purchased separately from the commission of the project.” Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York, a non-profit gallery specializing in the intersection of art and architecture, opened in 1982 at 51 Prince Street. As a producer of new work and new energy it promptly exhibited architects and artists such as Diller + Scofidio, Morphosis, James Wines, Lebbeus Woods, Steven Holl, Dan Graham, Dennis Adams, Jenny Holzer, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Wolf D. Prix, Tadashi Kawamata, Peter Cook and Christine Hawley, Mike Webb, Enric Miralles and Carme Pinós, Mel Chin, Camilo José Vergara, Muntadas, Matthew Ritchie, Julia Scher – many of them at a very young age. The first Architecture Biennale did not take place until 1980 with the Strada Novissima of Paolo Portoghesi (preceded by a small number of exhibitions of architecture within the Art Biennale, starting in the mid-1970s with the Vittorio Gregotti years). The first museums and archives of architecture are also a postmodern phenomenon (including CCA in Montreal and the Building Museum in Washington, D.C.).

It is not by chance that at the same time that architecture started to get its own territory in museums, galleries and biennials, artists started to take over the architect’s territory. In the 1976 Biennale “Ambiente/Arte,” organized by Germano Celant, Dan Graham built his “Public Space / Two Audiences”, a room in the shape of a golden mirror rectangle divided into two square rooms by an acoustic pane. One of the far walls was a mirror, and the other far wall was white. Graham said that the Venice Biennale and other art fairs are like world’s fairs, in which countries have their own pavilions, and art is the commodity. In Venice, he attempted to upset the system by making the audience into the exhibit. Visitors to the pavilion would see themselves seeing themselves. They have become the commodity. The pavilion complicates the scene. The subject becomes the object.

Dan Graham is of course linked to the historical figure of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe by the idea of the glass pavilion. When commissioned to build the German Pavilion for the International Exhibition in Barcelona in 1929, Mies asked the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, what was to be exhibited? That is a normal question for an architect. What is this building for? An artist never needs to ask that. The answer was: “Nothing will be exhibited. The pavilion itself will be the exhibit.” [1] Interestingly, Mies was being treated here as an artist. The pavilion doesn’t even have plumbing. If for Matta-Clark the difference between architecture and sculpture is that one has plumbing and the other not, the Barcelona Pavilion is art. It was precisely in the absence of a traditional program that the pavilion became an exhibit about exhibition. All it exhibited was a new way of looking. Viewing itself was on display, rather than objects to be seen.

Exhibitions in the 20th century acted as sites for incubating new forms of architecture that were sometimes so shockingly original, so new, that they were not even recognized as architecture at all. The Barcelona Pavilion, widely understood in the architectural world today as the most influential building of the twentieth century, was in fact seen by “nobody”. Despite its prominent position in the layout of the 1929 International Exhibition in Barcelona, even journalists sent by professional architectural magazines passed it over entirely, unable to detect its significance.

Some local journalists with no particular training in architecture provided the only testimony to its existence. They commented on the mysterious effect it had, “because a person standing in front of one of these glass walls sees himself reflected as if by a mirror, but if he moves behind them he then sees the exterior perfectly. Not all visitors notice this curious peculiarity whose cause remains ignored.” [2] It is necessary to return to this kind of fresh statement to understand the surprise that a glass building must have produced in 1929, something that – as Alison Smithson put it – a generation that had grown up around Hilton International hotels may have difficulty imagining. [3]

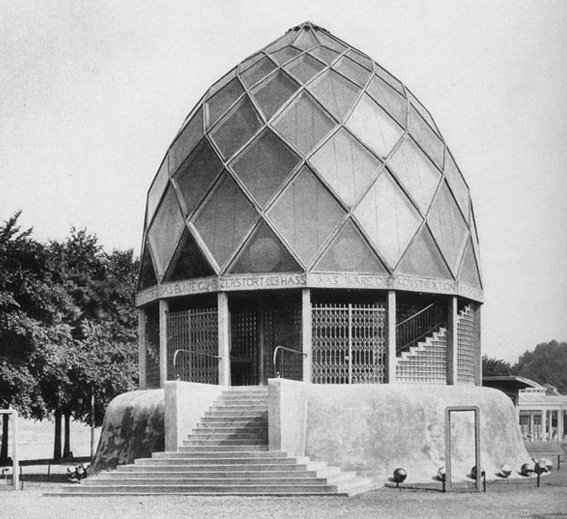

Bruno Taut, Glashaus-Pavilion, Kölner Werkbundausstellung, 1914

It was only in the 1950s, in the aftermath of the 1947 exhibition of Mies van der Rohe at The Museum of Modern Art, organized by Philip Johnson, that the Barcelona Pavilion burst into every architectural publication and was hailed as the most beautiful building of the century. A building that was known only through photographs (it was dismantled at the closing of the exhibition in Barcelona and its fragments lost on its return trip to Germany), became the most significant monument of modern architecture. The most extreme and influential proposals in the history of modern architecture were, in fact, made in the context of temporary exhibitions. Think about Bruno Taut’s “Glashaus” (the pavilion for the glass industry in the Werkbund exhibition of Cologne of 1914), Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s L’Esprit Nouveau Pavilion in Paris (1925), Konstantin Melnikov’s U.S.S.R. Pavilion in Paris (1925), Mies and Lily Reich’s Silk Exhibition, Berlin (1927), Le Corbusier and Xenakis’ Philips Pavilion in Brussels (1958), Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Dome for the American Exhibition in Moscow (1959) and his United States pavilion for the Expo ’67 in Montreal, Eero Saarinen and Charles and Ray Eames’s IBM pavilion for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, Frei Otto’s pavilion for the Expo 67 in Montreal, The Pepsi Pavilion for Expo 70 in Osaka by E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and technology), Coop Himmelb(l)au’s The Cloud, a prototype for future living designed for Documenta 5 (1972), Aldo Rossi’s Il Teatro del Mondo, a temporary theater built for the Venice Architecture Biennale of 1979 to recall the floating theaters of Venice in the eightteenth century popular during carnivals, and so many others. The tradition of the pavilion as the site of architectural experimentation continues into the turn of the century with such mythical projects as Diller + Scofidio’s Blur Building in Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland, a media pavilion for Swiss Expo 2002 now destroyed, and the series of pavilions that spring up every year at the Serpentine in London (Toyo Ito, Oscar Niemeyer, Rem Koolhaas, Ólafur Éliasson, SANAA).

If modern architecture is exhibition, you can also argue that the exhibition of modern architecture is a form of architecture. Let’s go back to the 1947 Mies exhibition at MoMA. The exhibition was significant, according to Charles Eames, as if an early warning of the symptom that Krauss describes almost half a century later, not because of the individual objects on display, but because of the organizational system the architect had devised to present them, which communicated, in his view, the idea of Mies’s architecture better than any single model, drawing, or photograph could. Eames wrote: “The significant thing seems to be the way in which he [Mies] has taken documents of his architecture and furniture and used them as elements in creating a space that says ‘this is what it is all about’.” [4] Eames was impressed by the zooming and overlapping of scales: A huge photomural of a small pencil sketch was seen alongside a chair towering over a model next to a twice life-size photograph, and so on. He also noted the interaction between the perspective of the room and that of the life-size photographs. The visitor experienced Mies’s architecture, rather than a representation of it by walking through the display and watching others move. It was a sensual encounter. “The exhibition itself provides the smell and feel of what makes it, and Mies van der Rohe, great.” [5]

What I would like to suggest is that the tradition of temporary pavilions is a form of performance, more specifically a form of urban performance. In assembling their experimental prototypes architects become urban activists. The buildings always subvert the everyday logic of the city. For example a domestic apartment interior from a skyscraper can suddenly appear within a park as with the L’Esprit nouveau pavilion of Le Corbusier in 1925. And this subversion of urban norms is also collective. Every fair, festival, and biennale produces a kind of hypothetical urbanism. They create a temporary city within a city. This is obvious in biennales like Venice, with its own streets lined with pavilions, but it is equally true when installations and events are dispersed throughout a city, as with Perfoma or Storefront’s “Performance Z–A”: A “Pavilion and 26 Days of Events” which were held inside the hula-hoop dome designed by the Seoul architect Minsuk Cho in 2007. With each of these exhibition-events, there is a special map to guide visitors through an alternative urbanism that is temporarily superimposed on the existing city. The usual urban circuits give way to new patterns and the performance of temporary architecture, like that of an artist, provokes new movements, new interactions, and new thinking. This confusion, even dissolution, of the art object into a kind of landscape experience is equally a dissolution of the line between the inside and outside of the museum. As architecture enters the space of exhibition and systems of exhibition enter the street, new kinds of museums, or post-museums, become possible, and that seems to me a good thing.

Beatriz Colomina is an architectural theorist, professor of history and theory at Princeton University School of Architecture and the Founding Director of its Program in Media and Modernity

Image credit: 1. Courtesy Galerie Meyer Kainer, Vienna

Notes

| [1] | As quoted in Julius Posener, “Los primeros años. de Schinkel a De Stijl”, in: A&V. Monografías de Arquitectura y Vivienda, 6, (1986), p. 33; my translation. |

| [2] | Local journalist from Barcelona reviewing the pavilion, quoted in Jose Quetglas, “Fear of Glass. The Barcelona Pavilion”, Revisions 2, ed. by Beatriz Colomina, New York 1988, p.130. |

| [3] | Alison Smithson, in conversation with the author. |

| [4] | Charles Eames, “Mies van der Rohe” (photographs by Charles Eames taken at the MoMA exhibition), in: Arts & Architecture, December 1947, p. 27. |

| [5] | Charles Eames quoted in Digby Diehl, “Q & A. Charles Eames”, Los Angeles Times WEST Magazine, 8, 1972, p. 14. |