The Possibility of Life at the Systemic Edge Three questions for Saskia Sassen

Hilary Koob-Sassen, “Vista of World Organs" from the project "Models of Aggregate Endeavor” (detail), 2001-ongoing

Hilary Koob-Sassen, “Vista of World Organs" from the project "Models of Aggregate Endeavor” (detail), 2001-ongoing

The macro geo-political dynamics currently shaping our world cut across all familiar historical boundaries, argues scholar Saskia Sassen in her new book, “Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy.” For this reason, the driving mechanisms, though operating with devastating force, she claims, effectively go unseen.

Here, Sassen responds to Texte zur Kunst regarding the impact this emergent psycho-geography might have on conventional understandings of a cultural “outside” and the creative potential the so-called systemic edge might hold therein.

Texte zur Kunst: In your recent book, “Expulsions,” [1] you examine the macro ramifications of a critical social shift: the trend, beginning around 1970, away from Keynesian economic models toward mass deregulation and privatization. You observe that this activity has had grave consequences, causing the exclusion of vast segments of the global population from the world’s economic infrastructure. It may seem a perverse connection to make, but we are interested, in this issue of Texte zur Kunst, in understanding how these contemporary dynamics might square with the classic notion of “bohemia” – a state of classlessness brought upon a certain demographic in the wake of great structural/political change – and whether the fading of “bohemianism” as a romantic artistic ideal (one that highly values dropping out of the mainstream) might be linked to an underlying sense that true disenfranchisement is again a very real threat. In your estimation, can a parallel be made here? Are we truly experiencing a reconfiguration of power so great that the mass-cultural desire to willfully exit capitalism is being supplanted by efforts to avoid being expelled from it? Will the option of “dropping out” soon become one only of extreme privilege?

Saskia Sassen: This is an extremely compelling thought. In the last paragraph of my book, I ask whether the spaces of the expelled have become a key subject for research given their extraordinary diversity. The spaces to which I am referring range from those generated by the foreclosure crisis in the United States (which in the past decade, has forced some 30 million people from their homes) to land grabs in the Global South that have expelled millions of rural farmers from their livelihood, to worldwide environmental destruction that has expelled pieces of the biosphere herself, leaving us with large regions of dead land and dead water. With so many different pathways into destruction, we might wonder what is being constituted in these places. It also leads me to ask whether we are actually seeing the making of deep processes that cut across familiar divisions – global south/global north, east and west, to mention just two familiar ones. In “Expulsions,” I argue that these cross-cutting processes can be thought of as conceptually subterranean … not because they are beneath the ground but because they have not been conceptualized, which would have made them visible.

It is intriguing then, to ask whether the spaces of the expelled might become one site for today’s equivalent of the historic bohemia. I had not thought about this connection you make between inequality and bohemia or the notion that the spaces of the expelled are marked by such desperation that there is no room for a bohemia to emerge. As someone who is keen on recovering the material practices of the historical bohemia – a social condition defined as much by possibility as by constraint – I tend to think that replications or extensions of bohemian life are difficult, even though some more generic version of “bohemian life” could be replicated. Consider the assemblage of elements that had to come together to make historical bohemia happen: a dense city with enormous diversity in its population by income and by class; a grand, orthodox, partly state-regulated system for “the” arts; an extraordinary mix of refugees exiled from countries where they or their families often were either elites or bourgeois. All together, this might have meant that poverty in a city such as Paris could have been partly an adventure, something feeding a romantic spirit. I think today’s spaces of the expelled are spaces of extreme hardship with very little romanticism built in. What could come out of this type of space? Possibly a hard-hitting form of critical art.

What we do see today are stagings of bohemia inside the system, so to speak, as well as the tension of growing inequality. Ugly, poor, industrial or commercial parts of a city that have some artists and craftworkers and low-income workers become more attractive to potential residents when branded with notions of bohemia. It sounds so much better than gentrification. Bohemia is de facto a cleansing name for such an area, enabling a rise in all prices. Richard Lloyd discusses this in his book “Neo-Bohemia: Art and Commerce in the Postindustrial City” (2006). The romanticizing narrative of bohemia that Lloyd studies was partly produced by those who did not belong to it. The exoticizing of what was an ugly, poor, industrial/commercial neighborhood made it attractive, thrilling, a place outside of the mainstream. This is bohemia as aura. This aura is also a kind of power, however, and one that was partly of use to the historic bohemia. Today the landscape is radically different though. While artists can unknowingly help glamorize a devalued site, once it is glamorized, many of them have to leave it. Interestingly, Lloyd also finds that many of the artists in the area he studied were actually designers producing for tech firms, online advertising firms, and such.

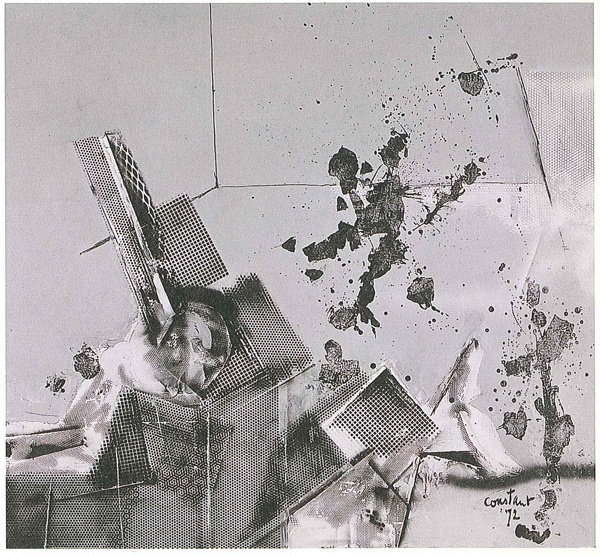

Constant Nieuwenhuys, "Espace en destruction", 1972

Constant Nieuwenhuys, "Espace en destruction", 1972

Texte zur Kunst: In your book, you mention “global cities,” positioning them as key sites of intervention/possibility in this current phase of accelerated capitalism. Can you elaborate on this? Might this relate to the trend, today in the cultural sphere, towards operating from within the mainstream, mining it culturally and politically, rather than fabricating subculture in the dead land of the periphery?

Saskia Sassen: This is interesting. Whenever dealing with a thick category such as “city,” I must first sufficiently remove myself from it. Given this, I would posit that the city, especially if global, is a complex, but nevertheless incomplete system. In this mix of complexity and incompleteness lies the capacity of a city to outlive other, more formal and powerful but closed systems: a mega-corporation, for example, or a government, an office park, or a gated community. Important to my analysis is the fact that it is in cities where those without power get to make a history, a culture, a politics – they are not going to make these things in an office park. Rather, it takes the anarchic, complex, ever-moving energy of a city. A city is much more than mere density: An office park is dense but it is not a city. This is the good side of global cities: They are large, full of talent and surprising options, or options that flow in unexpected directions. I’m thinking here how the tech community in global cities in part cohered to meet the demand for developing software for finance and how often this in turn generated new cultural modes, new video/digital-based forms of art production and, with them, new types of discursive art/film vectors. On the other side, the global city is also a site where the market can take over, and in that sense, suffocate art, even if many artists manage to survive making their own work while doing diverse little jobs for commercial firms. Again, this might use the aura of bohemia but it is quite unlike the historic bohemia.

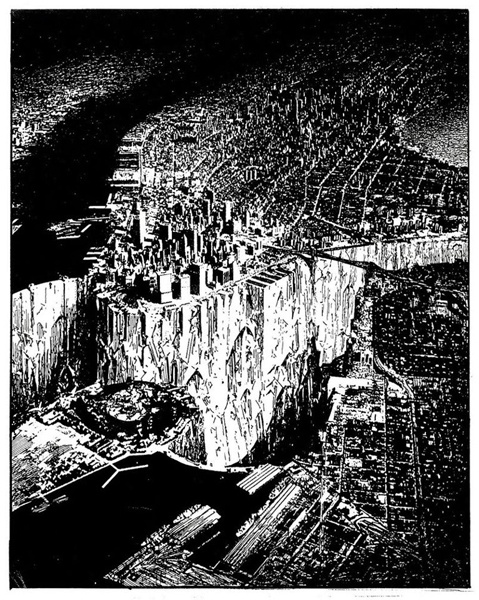

Lebbeus Woods, “Lower Manhattan”, 1999

Lebbeus Woods, “Lower Manhattan”, 1999

Texte zur Kunst: You speak about intangible sites of power, an oppressor that is not a discrete party, but “a complex system that combines persons, networks, and machines with no obvious center.” Given this, how can one establish autonomy from the system now? Or is a subject’s desire to establish “autonomy” – meaning not just independence but freedom plus the agency to act – no longer a crucial/necessary aim?

Saskia Sassen: A key challenge now is indeed negotiating the emergence of predatory formations. These may be constituted, yes, by powerful people and firms, but they are fundamentally part of a much more complex assemblage of legal and accounting systems, technical capacities, and embedded logics of power. In turn, they are much more elusive to apprehend and disentangle than the “super rich.” I argue that simply eliminating the super rich is not going to solve the inequality problem. Likewise, the task of securing a modicum of redistribution is now proportionately more challenging. Many of the old ways may not be enough given that achieving the degree of concentrated wealth that we have today took more than greed; it required, let’s say, systemic help. For example, the complex legal and accounting innovations that have allowed major firms to avoid a growing share of their taxes.

What we are seeing in this may well be a new mode of capitalism: Brutal and elementary in its aims yet embedded in complex systems. The key here for me is brutal and elementary. We can contest these predatory formations but not on their own terms. We must first exit that systemic logic. This can still mean working within the larger society. A very simple example is urban agriculture: It exists outside of the corporate food industry, yet can coexist with it, though indeed at this point, urban agriculture is far from being able to satisfy the food needs of an entire city.

Port of Singapore

Port of Singapore

But one issue your question makes me think of is to what extent the space of the expelled is another position from which to fight. In my book, I speak of the “systemic edge,” a conceptual region that has nothing to do with geographic borders. The key dynamic at this edge is expulsion from the diverse systems in play – economic, social, biospheric. The systemic edge is the point where a condition takes on a format so extreme that it cannot be easily captured by the standard measures of governments and experts, and thereby becomes invisible, ungraspable. In this regard, that edge also becomes invisible to standard ways of seeing and making meaning. And here I wonder whether the historic bohemia actually was a sort of systemic edge, and in that sense helps us see that there are modes of being in this world that thrive at the edge of systems. And artists are going to be better at this than traditional accountants or lawyers.

It could then be that at least some components of what I refer to as the spaces of the expelled could function as a new type of bohemia – not the aura of bohemia I criticized earlier in this exchange, but an actual zone of hardships that nonetheless allows some who have been expelled to be makers. This would not however be enough to counteract the devastations of these logics of expulsion: the millions who are left with nothing, the displaced who will never go back home, the vast stretches of dead land and dead water. Nonetheless it could still be a genuine bohemia.

It is in the spaces of the expelled where we find the sharper version of what might be happening inside the system in far milder modes and hence easily overlooked as signaling systemic decay. I have positioned my inquiry at the systemic edge to privilege this zone conceptually – one wherein conditions take on extreme forms, so extreme that they escape our conventional means and measures of representation.

Notes

| [1] | Saskia Sassen, Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy, Cambridge/MA: Belknap/Harvard University Press, 2014 (forthcoming in German from S. Fischer Verlag, 2015). |