No Hidden Assets Andrew Durbin on Karl Holmqvist at Gavin Brown's Enterprise, New York

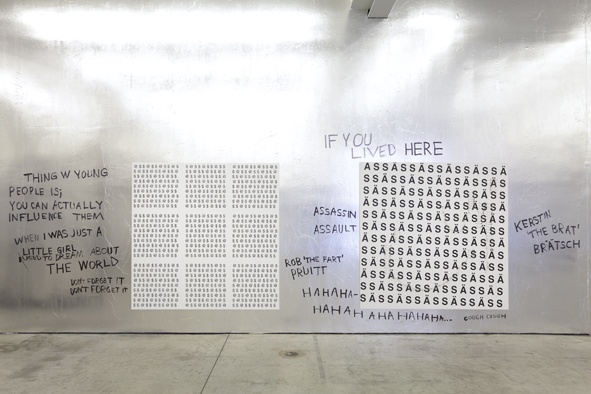

Karl Holmqvist, “Here’s Good Looking @U, Kid,” Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York, 2015

Karl Holmqvist, “Here’s Good Looking @U, Kid,” Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York, 2015

In “The Electronic Revolution” (1970), William S. Burroughs famously diagnosed language as an unidentified virus. “The written word,” he wrote, “has not been recognized as a virus because it has achieved a stable symbiosis with the host,” a stability that enabled it to become an instrument of ubiquitous psychic control. Cut-ups, slippage, appropriation, feedback, repetition, all of these are the disruptive literary techniques that, for Burroughs, both ensure and combat pernicious language-control and generate new logics of association outside the normative parameters of the “objective reality” formulated by the virus. While not offering a cure, Burroughs clarified (somewhat, at least) the virus’ symptoms and provided a conceptual framework for interpreting its life in the forthcoming age of the network.

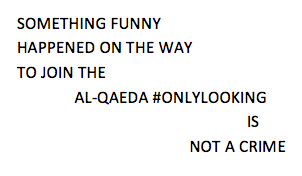

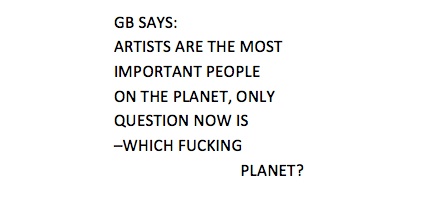

For Karl Holmqvist, the Berlin-based artist and poet whose recent exhibition “Here’s Good Looking @U, Kid” opened this spring in New York at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, it’s like that, only it’s a lot like Sia’s “Chandelier,” too, a song – as the Australian pop singer recently told Howard Stern – named as such because audiences, she explains, most desire songs with big metaphors in their titles. “Chandelier,” like Holmqvist’s own work, refuses to say what it means without saying everything first, often in the simplest way possible: “I’m going to swing from the chandelier. I’m going to live like tomorrow doesn’t exist,” Sia sings, reclassifying the generic as the emotionally profound. Holmqvist, whose work often appropriates the viral language of pop, might echo her back, only in a repetitious drone, reverting the profound to the generic and banal. In a recent performance, for example, Holmqvist recast Beyoncé’s now-famous dictum “I woke up like this” (from her song “Flawless”) as a lengthy canticle deprived of the emotion that makes her recitation of it so powerful. “I woke up like this,” Holmqvist repeats flatly over and over again, “I woke up like this.” It’s punk plagiarism, sucking out the affective lyricism of the pop ecosystem to flatten out all those very-much-felt feelings into a poetry of surfaces – and tedium.

At Gavin Brown, the viral language of both pop and the written word is everywhere. Holmqvist papered the gallery walls in aluminum foil, scribbling over them with clichés, found text (much of it from the news), references to friends and other artists (“ROB ‘MONEY OR YOUR LIFE’ PRUITT”), and word games in graffiti-like poems. One wall at the front of the gallery reads in the lower corner:

Holmqvist has described American English – his preferred lexicon – as a slippery language “imposed on us,” but one that “allows for reinvention.” For the Swedish artist, this reinvention frequently takes the form of cut-up jokes sourced from the canned and awkward grammar of the New York Times’ headlines to the clipped and networked hashtags, memes, and slang of the web, making for a poetry that doesn’t so must resist imposition as it does mock its homogenizing banality.

Holmqvist’s humor owes much of its force to a kind of punk polemics, even self-consciously so (“I ALWAYS THOUGHT / A PUNK WAS / SOMEONE WHO / TOOK IT UP THE / ASS,” he writes on one wall, followed by: “WILLIAM ‘ASS’ BURROUGHS”). Differing from punk’s confrontational pose, Holmqvist doesn’t so much intervene in culture as he does draw it forward, cleaving phrases and words from their original contexts in order to highlight their vacuity within the various imperial markets those words belong to. Holmqvist covered part of one wall, for example, with a New York Times article on the 200 shell companies that funnel secret, foreign money into New York real estate, writing out the percentages of the top five buildings invested with the most foreign money in the city. He also included a bit.ly link to the original article.

Between the writing on the walls, Holmqvist placed a number of large paintings, all of them grided or checkerboard variations of the word ASS repeated across the canvas. The paintings follow Merlin Carpenter’s insistence on the flimsiness of those systems of value that allow any gesture as sly as Holmqvist’s to be called art in the first place, amplifying the show’s ongoing joke as one of implication and complicity. If you buy a painting that says ass, are you an ass? What if you make it? What if you put it on a wall? What if you write about it? Between two such works he wrote, “Real ass tight / speculation,” a nod to a market that prefers the joke (if there is one) to be on all of us, if it’s going to be on anyone. Holmqvist frequently reduces art objects to their most basic signs (often words or arrangements of letters), a wink to the art market’s preference for the big, bold, and insider, branding the alphabet for our culture of ubiquitous logos. Again, Holmqvist, like Sia, prefers language at its simplest, most open. To this, Holmqvist included a few monumental (if overstated) rectangular sculptures of four letter words. One spells out: FUCK. Another: PUNK. Another: LUVV. A smaller one composed of lights simply reads LIKE. That was enough – sort of.

Karl Holmqvist, “Here’s Good Looking @U, Kid,” Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York, 2015.

Karl Holmqvist, “Here’s Good Looking @U, Kid,” Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York, 2015.

In collaboration with Holmqvist, Rirkrit Tiravanija placed five televisions in the backroom of the gallery that occasionally played his “Untitled 2014 (Karl Holmqvist Reads),” a series of video portraits of Holmqvist. Variously set in casual domestic spaces, Holmqvist reads from his work with his charming, stilted pace as he repeats word games and found phrases. The scenes are simple. In one, Holmqvist sits on a balcony in a tank top with a thin scarf draped around his neck, a table of flowers behind him. He reads. This is what Holmqvist does best. While poetry, even poetry in the art world, remains mostly out of reach of art’s markets, Holmqvist, in so thoroughly incorporating it into a gallery setting – including some of the largest and most desirable in North America and Europe, like Gavin Brown – establishes a particularly mercurial space for himself, one that seemingly resists the market even as it finds itself a participant in it. Unlike Tiravanija’s work, which demands audience participation, Holmqvist’s work relies on language and poetry to invite our attention, often coyly:

Tiravanija’s videos return the artist to his mesmerizing performances, the strength of which has always seemed to lie in their unabashed smallness. Against the show’s overwhelming scale, Holmqvist and Tiravanija presented poetry at its simplest, a throwback to its life on American public access TV in the 1980s and 90s with shows like “Poetry Spot,” which featured poets reading in mostly empty rooms or on rooftops. Likewise, the room where Karl sits in “Untitled” doesn’t contain large paintings or writing on the walls or over-large sculptures; instead, it contains Karl, whom I had been looking for all along.

Karl Holmqvist, “Here’s Good Looking @U, Kid,” Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York, March 7–April 25, 2015.