Animated Gifts in the Exchange System Reflections on Jack Whitten’s Painting, on the Occasion of the Exhibition “Jack Whitten: Jack’s Jacks” at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin

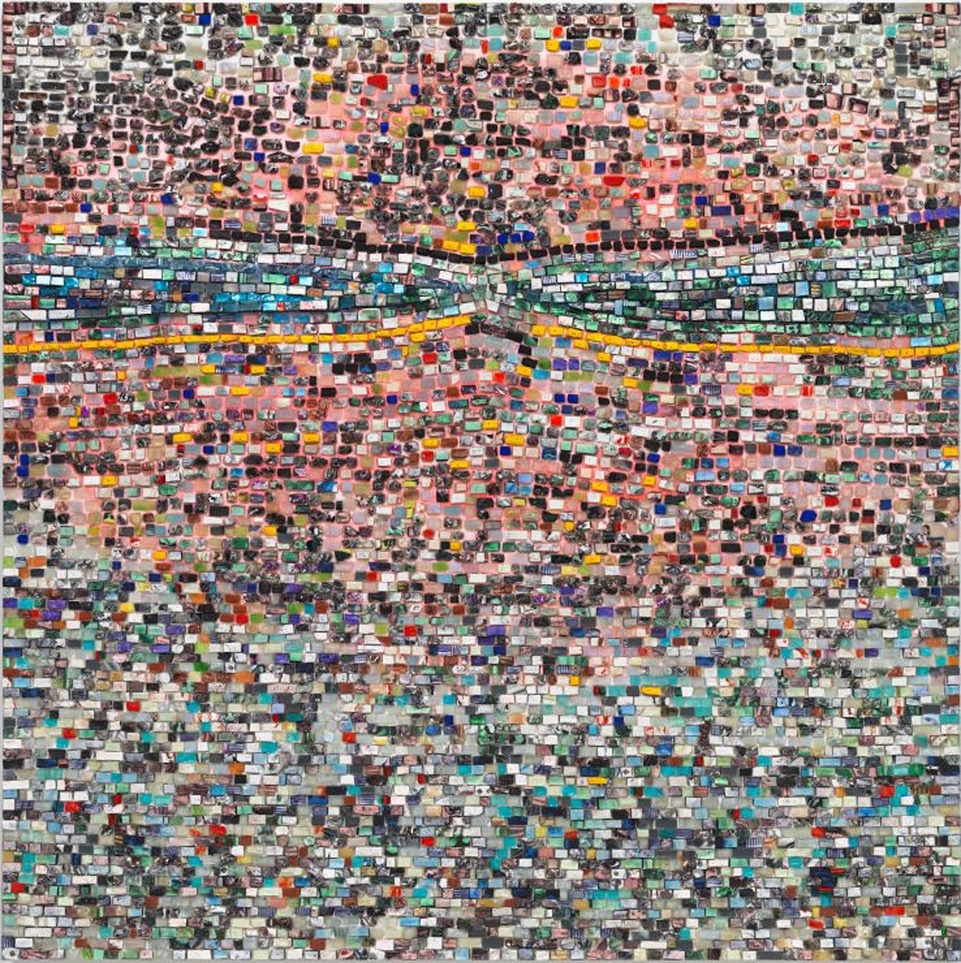

Jack Whitten, „Quantum Wall, VIII (For Arshile Gorky, My First Love in Painting)“, 2017

1. Animated Material

In Jack Whitten’s work, it is the suggestive forces of the material – and not ideas – that are foregrounded. The fact that Whitten has repeatedly (and vehemently) distanced himself from Conceptual Art, or more precisely, from a traditional understanding of Conceptual Art as an idea/concept-based form of artistic practice – is, in my view, also related to his focus on the inherent forces of his materials. [1] And in line with so-called New Materialism currently under such heavy debate, Whitten does not see matter as a mute, disposable mass, but rather as a powerful thing. [2] However, for his material to come across as “animated,” it is not just certain methods of aesthetic production that are required. There also needs to be an observer ready to project this animation – two factors often not prioritized in those approaches that refer to New Materialism.

It is especially in Whitten’s “Memorial Paintings” – produced after 1968 and on which the Hamburger Bahnhof exhibition is rightly focused – that this interplay of suggestive material, vitality effects, and vitalistic projection can be traced more precisely. A variety of methods is evident in these paintings, starting with the titles and their dedicatory character – such as Clocking for Stanley Kubrick (1999) – and relief-like surfaces made of colored acrylic pieces up to the way the working process gets emphasized with which Whitten, who died in 2018, was able to “ensoul” his paintings, transforming them into quasi-spiritual objects. In my opinion, the fact that Whitten’s “Memorial Paintings” per their titles appear as gifts for mostly deceased people contributes to their “animated-ness” as well, as much as their dynamic color surfaces, which often profess to transport the soul of the deceased. In addition, Whitten’s paintings often show tool marks on their surfaces – thus vitalizing them and directly augmenting them with something of the artist’s lifetime and working time. Given this, it is not just a question of working out how exactly (i.e., with what artistic methods) Whitten succeeds in vitalizing his works. For his work to be perceived as “animated,” certain methods of aesthetic production need to have been interwoven with an animistic reception. However, there are also sociohistorical reasons why the material plays an active, vital role in Whitten’s work. My thesis here is that the specific charge of his material leads to an impression of “soulfullness” in his works, and that this symbolically advances their circulation in the art system. Step by step, however.

2. Sculptures as Blueprints

As soon as Whitten cuts his material – or more precisely, the acrylic paint he uses – into small pieces and sticks these onto the canvas, he gives his paintings a mosaic-like impression; they thus appear object-like and their surfaces “agitated.” In my view, it is the aesthetic principles of his wooden sculptures (unfortunately not shown in the exhibition) that are revisited and driven forward in the “Memorial Paintings.” [3] From my point of view, these rarely shown sculptures – hybrids of African sculpture, folk art, and Cycladic objects – provide the blueprint for his painting. Some of them, for example, have nails on their surfaces, through which they formally communicate with the Minkisi sculptures of Central Africa, which were likewise studded with nails, and which functioned as containers for supernatural forces. Whitten’s nails, with their reference to African sculptures, also ensure that his objects appear to possess magical power. The sculptures’ nails are matched in his paintings via the cut pieces of colored acrylic – Whitten called these “tesserae.” In a film at the start of the exhibition, Whitten can be seen sticking these tesserae to the surface with a pointed object, rendering dots on the surfaces of some of the small stones. Like the nails, these irregularly cut color elements also provide a powerful, dynamic surface. In any case, it is in Whitten’s work with the tesserae that the potential for vitality traditionally associated with color enters a new phase, with the three-dimensional color pieces enhancing the sensual/haptic quality of the color even further. In the monumental painting dedicated to Prince, Quantum Wall (A Gift for Prince) (2016) – its purple tones in keeping with Prince’s best-known song, “Purple Rain” – the three-dimensionality of the color pieces leads to the impression of a dazzling polychromatism that can change depending on where the viewer stands. Likewise, the objects and patterns on the surface of the painting Ode to Andy (1986) – taken from the living world, like stones, fish, and a silver metal plate – allude directly to Warhol’s Silver Factory, producing a surplus of everyday reality. But unlike in collage or assemblage, these references to life remain subordinated to color in Whitten’s work. Once again, it is Whitten’s material – color – that always retains the upper hand as the medium of impression: in Whitten’s work, color serves above all to represent the people honored in the titles of his works. It is not so much a carrier of expression; rather, its function is symbolic.

The dedicatory character of his “Memorial Paintings” can also be found in the sculptures. In this context, we can simply think of Whitten’s anthropomorphic John Lennon Altarpiece (1968), studded with nails, or the objects of protection for his family, such as The Guardian II, For Mirsini (1984). Through their dedications, the titles of these works function as paratexts, ensuring that each gift recipient or remembered or honored person remains present in the object itself. We can take Whitten’s Muhammad Ali image from his 1988 “Black Monolith” series (Black Monolith X (Birth of Muhammad Ali), 2016) as another example of how the memory of a person literally enters into the color and morphology of his paintings. At the lower end of a typical Whitten field of glued-on and cut-off color pieces there is a black, oval, encrusted, and Dubuffet-esque form that brings the figure of the absent Ali directly into play, as if he were risen from the debris-like ground of the image. By evoking the birth of Muhammad Ali, the title of this painting recalls his self-directed transformation from champion boxer Cassius Clay to athlete-cum-civil rights activist, a kind of rebirth, and one to which the abstract pictorial language of this painting clearly alludes.

3. Titles as Vivification Devices

It is, then, primarily the titles of Whitten’s images that have a “vivifying” effect. The Messenger: For Art Blakey (1990), for example, is a title that honors both the legendary jazz drummer Art Blakey and his band (The Messengers). The drummer’s almost extraterrestrial ability is captured merely using the cosmic atmosphere of this black-and-white grid, which from a distance resembles a universe densely populated with stars. It could be said that every “Memorial Painting” preserves what Whitten sees as the essence of the artistic or political achievement of the person honored in its title. In Whitten`s work, painting and title often stand in a metonymic relationship to one another: the meaning of the one is usually found in the other. So instead of producing a gap between the meaning suggested in the title and what the image presents us with visually – as is often the case with, for example, Dadaist or Neo-Dadaist paintings – with Whitten, we are usually confronted with correspondences: with the help of an abstract visual language, that with which the title is associated is confirmed in the image. Whitten’s black, largely monochrome painting Sweet Little Angel, For B. B. King (2015) is a fine example of this, having as it does a neon-sprayed string on its surface. Its function here is to represent a guitar string, i.e., the instrument that distinguished the blues guitarist B. B. King. The fact that Whitten`s paintings so often use an abstract visual language to depict that which is proclaimed in their titles may at times be read as somewhat redundant, too obvious. At the same time, however, the titles also charge the paintings they name with a specific history of time and culture. In addition to numerous jazz musicians, Whitten also paid tribute to several – mostly male – visual artists in his “Memorial Paintings,” first and foremost among these being his friend and mentor Norman Lewis, that influential pioneer of abstract painting to whom Whitten’s monumental Norman Lewis Triptych I (1985) is dedicated.

Jack Whitten, „Black Monolith X, Birth of Muhammad Ali“, 2016

4. One's Own Role Models

In the 1950s, Norman Lewis was the only African American painter to participate in the symposiums organized by Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning at Studio 35 in New York. [4] However, he was consistently erased by the official historiographies, as in the texts of Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, and Irving Sandler. [5] In this context, the monumental dimensions of Whitten’s Lewis painting Norman Lewis Triptych I can even be read as a kind of correction of the canon. Lewis’s emblematic and calligraphic-seeming pictorial language, however, is willfully both synthesized and broken down into its components. For example, it is the colorfulness of Lewis’s painting Untitled (1949), and not its conspicuous vertical structure, that Whitten, in his Lewis triptych, recalling Mondrian, transforms into a grid structure on a black background. Alongside Lewis, de Kooning was another major inspiration for Whitten, as can be felt in numerous gestural paintings from the 1960s, such as King’s Wish (Martin Luther’s Dream) (1968), and in the title of his seemingly photographic grid painting Bill’s Way: For de Kooning (1989). [6] In the latter homage, it is above all the broad brushstrokes and skin colors typical of de Kooning that Whitten literally dissects and analyzes with the help of a grid structure, thereby also immobilizing their effect.

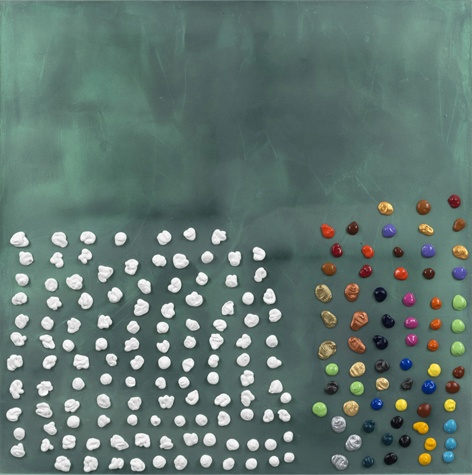

It would obviously be insufficient to comprehend his “Memorial Paintings” solely as a confrontation with various superegos or as an instance of Harold Bloom’s much-quoted “anxiety of influence.” On the contrary, they also bear witness to the existential necessity for a black artist in the New York of the late 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, who was also an abstract painter, to seek out his own role models (also from jazz) due to a lack of recognition and encouragement. [7] Jazz musicians honored in his paintings – such as John Coltrane or Bud Powell – ultimately represent the success story of that art form, to which Whitten then ties his references. Within the history of painting, there had at that time still not been a comparable rise to prominence for black artists. Whitten was instead confronted with a double exclusion: firstly, around 1971, his politically committed colleagues considered it to be “hugely unfashionable” [8] to paint in a non-representative manner; secondly, the art market – which is still today dominated by white actors – and the majority of art institutions remained for a long time largely closed off to him. [9] Forced for many years to earn his living as a teacher, debate and discussion with his students became enormously important to Whitten. Nevertheless, he did not correspond to the clichéd image of the obsessive painter genius who devotes his time exclusively to painting. [10] That Whitten necessarily had to approach his heroes of postwar art – such as Andy Warhol, Cy Twombly, and Ellsworth Kelly – from the outside because of his social marking as a “black artist” is made clear in paintings such as the homage to Ellsworth Kelly, One Hundred Ninety Pieces of Color: For Ellsworth Kelly #2 (2016), an image in which Whitten’s distinct approach to modernism is formally echoed. Kelly’s predilection for ready-made colors is built upon here in the form of colorful, glossy clusters of paint pressed directly out of the tube. Kelly’s impersonal recourse to commercial color charts has been replaced by a physical process of pressing that moreover results in pure material. Unlike Kelly, who sought to minimize the sensual potential of color, Whitten uses his Kelly homage to demonstrate the haptic and vivifying effect of color that is central to his work. Whitten thus refers to Kelly’s method in a way that both captures and – in so doing – transcends its exemplary character.

Even when Whitten appropriates the modernist topos of the grid, his position as being “from the margins” [11] is always latently in operation. Or, to go even further: in his variations on this motif, the modernist myth of the grid is taken, ad absurdum, as a guarantor of “flatness.” This is the case in Totem VI Annunciation: For John Coltrane (2000), for example – a multipart work that features clusters of mostly greyish pieces of acrylic paint. Both these color pieces and the grid formations they make up appear extremely crooked and slanted here. As with jazz, Whitten has used a strictly formal model – the grid – in order to simultaneously liberate himself from it. Omnipresent in his work are grids that appear organic, that curve, or whose outer forms have been rounded off, as evidenced by images such as Yankee Clipper: For Joe DiMaggio and Quantum Wall, VIII (For Arshile Gorky, My First Love in Painting) (2017). When Whitten takes the liberty in these works of producing crooked and slanted grids, it signals two things: that the tradition of the grid is not something he can take for granted, and that the modernist claim of the grid to overcome the figure-ground relation does not reach far enough. Whitten’s grids do not create the impression of flatness; rather, they suggest a three-dimensional, bodily form of vitality.

Jack Whitten, „One Hundred Ninety Pieces of Color: For Ellsworth Kelly #2“, 2016

5. Traces of Doing It Yourself

Alongside the titles, the color pieces, and those things cast with paint, visible traces of work in Whitten’s oeuvre also ensure that the latter is symbolically enriched with something of its creator’s lifetime and working period. In his seemingly graphical target painting Red Black Green (1979–80), and in the painting Zulu Tea Party (1979), with “wounds” on its surface, clear tool marks give evidence of Whitten’s working process. On the surface of Red Black Green, for example, the paint has been spread horizontally with an Afro pick. In Zulu Tea Party, one of Whitten’s homemade notched squeegees has torn visible stripes into the surface. It is therefore not only an “inscription of events and persons” (as per curator Sven Beckstette) that takes place in these paintings; they also bear witness to Whitten’s specific working method. [12] The fact that Whitten liked to resort to self-made or unconventional tools – such as giant squeegees (calling them “developers,” in reference to photographic processes), Afro picks, planes, saws, and wall trowels – articulates first and foremost the do-it-yourself character of his method. These tools are not only means to an end; they are significant in themselves, which is why Whitten occasionally presented them in exhibitions (such as at the Daniel Newburg Gallery in New York in 1994). The peculiarity of these tools seems to me to lie largely in the fact that they bring about both mechanization and an idiosyncratic form of personalization of his working method. With the Afro pick, for example, the significance of the hand is relativized and the painterly process mechanized, while at the same time, it also feeds a personal/identity-political moment into his work. Similarly, the self-built, monumental squeegee with which Whitten produced “slab paintings” such as Zulu Tea Party in one go does not merely perform the mechanization of the working process; it also performs its individualization. With the self-made squeegee, Whitten ultimately informs us that an artist must do everything themselves if they are not clearly embedded in the (characteristically Eurocentric and racist) tradition of painting. But at the same time, the self-made squeegee also signals Whitten’s affiliation to postwar modernism, in which squeegees were after all common among artists such as Ed Clark, K. O. Goetz, and Gerhard Richter. Whitten had in fact always claimed such modernity as a matter of course, typified by his declaration in the title of one of his images that the painter Ashile Gorky was his First Love in Painting.

6. Gifts with Obligations to Reciprocate

As suggested above, it seems to me that there remains an essential connection between the “dedicatory character” of Whitten’s “Memorial Paintings” and the proposition of their animated-ness (by way of color, title, color imprints, and traces of work). That Whitten characterized his paintings as “gifts to the people who inspired them” [13] can help point us in the right direction: according to the anthropologist Marcel Mauss, gifts are less inanimate things and more animated objects of exchange. [14] By examining archaic institutions, Mauss has shown that gifts must be returned on the assumption that a piece of their giver was contained therein and lived on with them. According to this, gifts are animated and must therefore be passed on. Whitten then modifies this animistic principle to the effect that it is not the soul of the giver but the soul of the recipient that his “Memorial Paintings” appear to transport. And it is precisely because they also function as quasi-magical ritual objects that they must, per Mauss, be exchanged. From this anthropological perspective, one could then interpret the gift structure of Whitten’s paintings as an attempt to force their entry into the economic cycle of the art market. Or, to put it another way: by presenting themselves as gifts – to Robert Rauschenberg, for example, as in the digital-looking Bar Code IV Lotto (A Gift for Robert Rauschenberg) (2008), or for Louise Bourgeois, as in Sainte Louise AKA The Tittie Painting for Louise Bourgeois (2010), which regrettably reproduces sexist clichés – they also make a claim on their participation in an exchange system that marginalized them for a long time. In the 1970s, Whitten himself is said to have been indignant about the fact that his paintings were traded below their value. [15] With these manifold animation methods, he took the risk of drawing back from the ideal of a serially and/or mechanically produced appearance of lifelessness (as aspired to by Minimal art and Pop art). At the same time, however, it was via the very dedication of his paintings to artist colleagues that he asserted his membership in the postwar canon. The fact that Whitten’s paintings now have institutional recognition and increasing market value is also due to structural reasons (such as the long-overdue commitment of numerous art institutions to “diversity”) and, consequently, cannot be attributed solely to the animistic potential of his works. Nevertheless, I believe that the various methods of animating them, including their presentation as “gifts,” have been symbolically conducive to their circulation and interchangeability.

It is at this point, however, that the question could be posed, with reference to Samo Tomšič’s critique of vitalism, as to the extent to which we are in Whitten’s case dealing with a “positive vitalism” – in the form of vivifying titles, materials suggestive of aliveness, and animated gifts – in which “negativity” falls by the wayside. [16] First and foremost, however, negativity seems to me to be something an artist must be able to permit themselves. As long as what a person is and does counts less than the identities and actions of others, procedures of positive-vitalistic self-assertion may be the order of the day. More so, if one understands the majority of Whitten’s “Memorial Paintings” as a kind of cult of the dead, then the absence of the honored could actually be interpreted as a sign of negativity. And the strength of Whitten’s “positive vitalism” seems to me to lie in the fact that it is not the artist himself who is celebrated as something quasi-living, but rather his social-artistic system of reference. Whitten himself is to some extent declared to be part of this vital structure; the others are thus always implicated in his “I.”

“Jack Whitten: Jack’s Jacks,” Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, March 29–September 1, 2019.

Translation: Matthew James Scown

Notes

| [1] | See some of Whitten’s remarks regarding this in Katy Siegel (ed.), Jack Whitten: Notes from the Woodshed, Zurich 2018, p. 176. A 1984 entry states “I must be careful not to depend upon conceptual thought.” Or an entry from 1986: “I don’t believe in Conceptual Art; if you can conceive of it then it’s not art but an illustration of an idea,” p. 190. Or on p. 233: “I must work against Sol Le Witt. Saw the ACE Gallery Show, 100% conceptual. Work against the conceptual.” |

| [2] | See his oft-quoted statement about his painting of black Congresswoman Barbara Jordan: “She is in that bucket.” The person portrayed would therefore be in the paint pot themselves. Quoted per Jeanne Siegel, Painting after Pollock: Structures of Influence, Amsterdam 1999, p. 40. |

| [3] | See the catalogue focused on his sculptures: Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture 1963–2017, New York 2018. |

| [4] | See the preface and acknowledgment in: Norman L. Kleeblatt/Stephen Brown (eds.), From the Margins: Lee Krasner/Norman Lewis, 1945–1952, New York/New Haven, CT 2014, pp. 11–13. |

| [5] | See Mia L. Bagneris, “Loner in the Dark: The Singular Vision of Norman Lewis and the Evidence of Things Unseen,” in: From the Margins, pp. 78–89, here p. 81. |

| [6] | For Whitten`s remark that "Abstract Expressionism was my academy," see the unpublished interview by Judith Olch Richards from 2009, "Oral history interview with Jack Whitten," https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-jack-whitten-15748. |

| [7] | See above, where he once again states how no one gave him support: "There was no encouragement from nobody." And on the 1970s: "The idea of a black artist doing these works and thinking that way, nobody paid attention to you." Richards, "Oral history interview with Jack Whitten." |

| [8] | See Darby English, 1971: A Year in the Life of Color, Chicago 2016, p. 73. |

| [9] | See an entry from 2012 in Katie Siegel (ed.), Jack Whitten: Notes from the Woodshed, Zurich 2018, p. 392: “I have survived with very little help from the ‘artworld’ the white artworld simply denies my existence.” |

| [10] | This was also due to the painting breaks Whitten took in the summer, during which he exclusively produced his wooden sculptures on Crete. |

| [11] | “From the Margins” was the title of the aforementioned Lee Krasner and Norman Lewis exhibition at The Jewish Museum in New York from 2014–15. |

| [12] | See Sven Beckstette, “Die Bedeutung der Abstraktion erweitern,” in: Jack Whitten: Jack’s Jacks, exh. cat., ed. by Udo Kittelmann/Sven Beckstette, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, Munich/London/New York, 2019, pp. 46–63, here p. 50. |

| [13] | Quoted after Katy Siegel (ed.), Jack Whitten: Notes from the Woodshed, Zurich 2018, p. 418. |

| [14] | Marcel Mauss, The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies, London 1990. |

| [15] | See Zoé Whitley, “Brotherliness: Melvin Edwards Reflects on 50 Years of Friendship with Jack Whitten,” in: Jack Whitten, Jack’s Jacks, pp. 129–137, here p. 136. |

| [16] | See Samo Tomšič, The Labour of Enjoyment: Towards a Critique of Libidinal Economy, Cologne 2019, p. 204. |