SKIN-DEEP Daniel Culpan on Jenny Saville at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Jenny Saville, “Hyphen,” 1999

A mountain range of flesh. Two vast heads – those of the painter Jenny Saville and her sister – with one’s chin resting on the other’s shoulder, like a pair of conjoined twins. The eyeline of one of the women stares intently off toward the right-hand side of the canvas, while the other appears to gaze down at the viewer with a kind of heavy-lidded indifference. Certain details seize the eye: the scarlet blemish beneath one sister’s lower lip; a patch of canvas next to the other’s mouth, where the paint has been scraped smooth.

Hyphen (1999) is the first work one encounters in “The Anatomy of Painting” at London’s National Portrait Gallery, the largest UK exhibition to date dedicated to Jenny Saville’s career. It bears many of the painter’s hallmarks: figuration that frequently pushes the proportions of the human body to extremes; a fascination with what can be seen on the skin’s surface; and a visceral realism that distorts and abstracts the body until it becomes a strange yet intimate landscape. If oil paint is Saville’s medium, then flesh is her material: stretched, sculpted, brutalized, caressed. As such, she finds herself in a line of painters who have made their names by turning a fastidious eye to the colors and textures of human flesh, from Raphael and Peter Paul Rubens in the Renaissance and Baroque periods, to Impressionists such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, to 20th-century artists such as Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon.

Born in England in 1970, Saville graduated from the Glasgow School of Art in 1992. Her vast female nudes, which force the viewer into a kind of submission, caught the eye of the collector Charles Saatchi, who exhibited a work by the painter in his now landmark “Young British Artists III” show in 1994. The painting in question, Plan (1993), is another of the early works that occupy the opening galleries of the show, which organizes Saville’s oeuvre in broadly chronological order. Monumental in scale, the self-portrait depicts the painter as nakedly contorted within the expanse of the frame: her head cut off slightly by the top edge of the canvas, she gazes down at the viewer with clenched teeth, arm clasped around her breasts. The scale renders her thighs a vast expanse, with geometric rings painted around the legs and stomach that make her body appear like a mapped land mass.

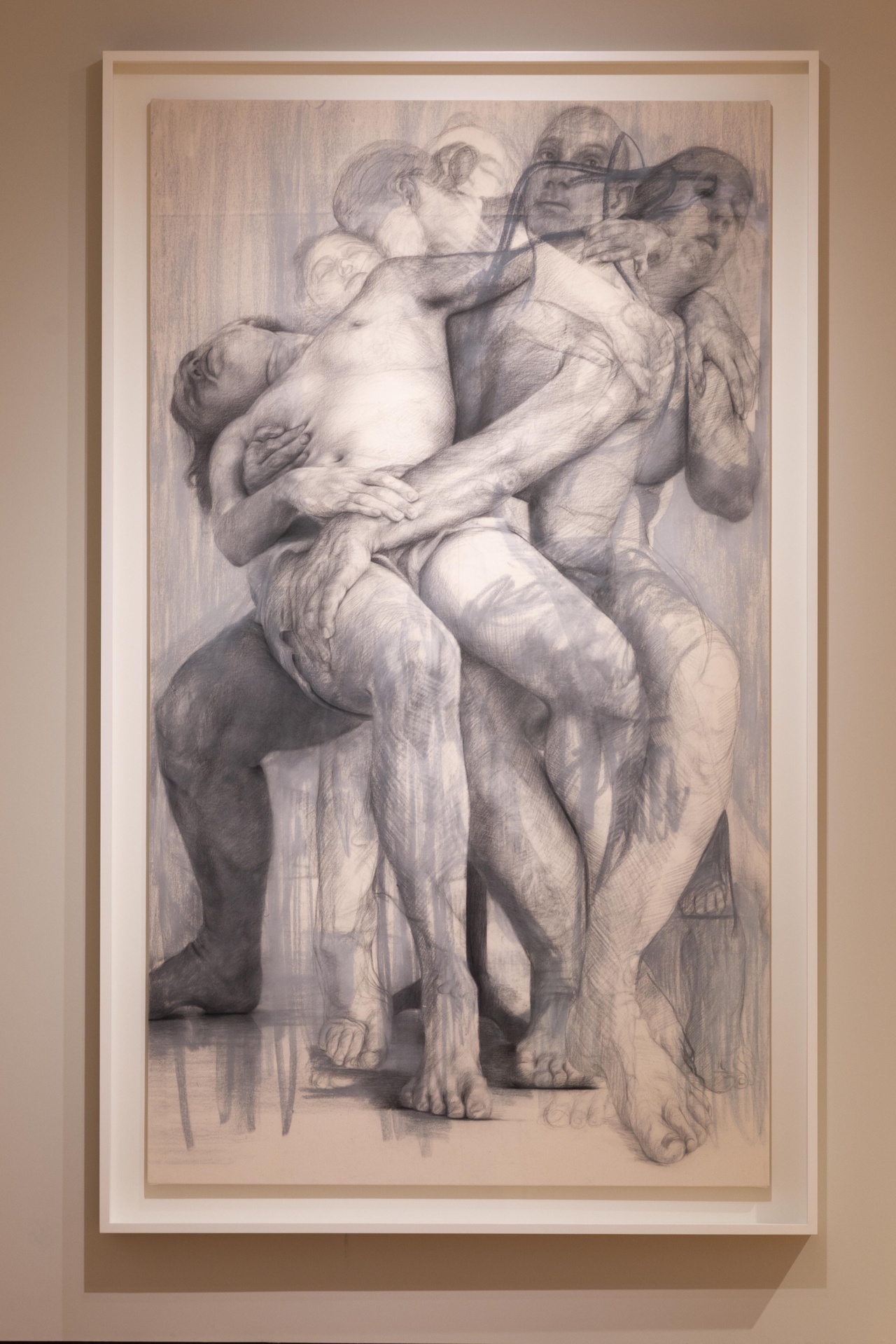

Jenny Saville, “Ruben’s Flap,” 1998-99

Saville pays forensic attention to the pigments and texture of flesh. The mottled ochres in the folds of a chin; the raw scarlet of a nostril; the faint, bluish suggestion of a vein or the umber coloring of a nipple. In Interfacing (1992), impastoed paint emphasizes the model’s warty-looking skin and almost cratered cheek, which bears a crescent of purple under the eye. Ruben’s Flap (1998–99) combines the hyperrealism of the female nude with a kind of hall-of-mirrors discontinuity; corporeality is fractured, with a single body reconfigured into three strangely overlapping angles. (The title is taken from the name of a breast reconstruction technique, yet also points to Saville’s feminist re-examining of the fleshy female form, in a playful allusion to the Old Master Rubens himself.)

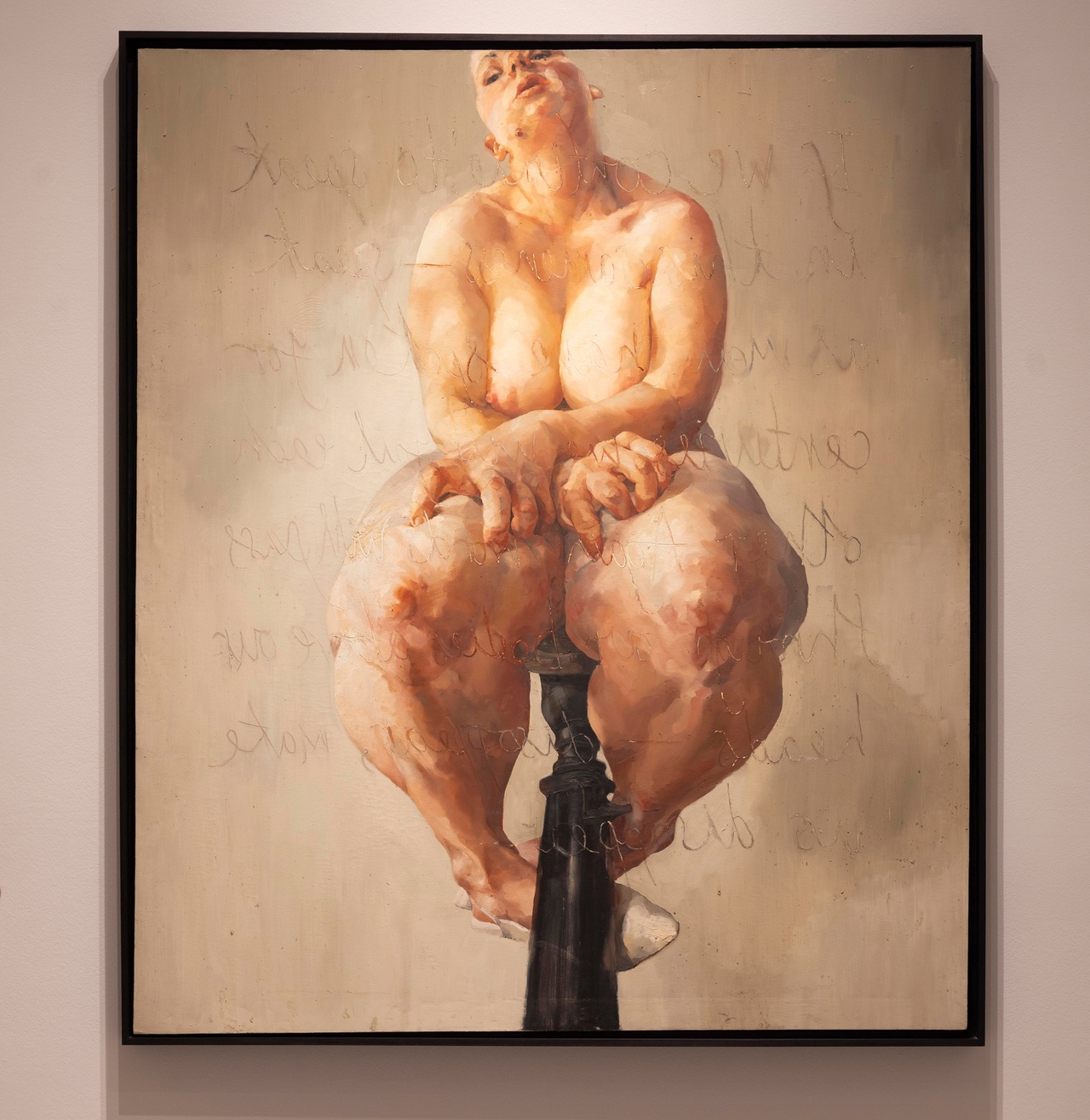

Faced with the vertiginous expanse of these canvases, the viewer can end up feeling like a fly trapped inside a meat freezer. The force of these paintings is generated from the way Saville translates oil paint directly into sensation – she pours movement into these bodies, making them suffocate, envelop, mutate, transform. In 1992’s Propped, a woman perches on a stool, her thighs rendered like monoliths. There’s a physical directness, both fragile and mighty, to the way her fingernails dig into her legs. The model’s seeming monstrousness (certainly in contrast to the waiflike heroin chic that reigned on catwalks and magazine covers as the aesthetic ideal of the ’90s) is paired with the delicacy of her white slip-on shoes. A quote from the Belgian-born French feminist and philosopher Luce Irigaray ribbons backwards across the canvas, designed to be decoded by the mirror that was originally displayed facing the work: “If we continue to speak in this sameness – speak as men have spoken for centuries, we will fail each other.” While this quote implies a certain feminist agenda to the exhibition, the question of how exactly it relates to the works on display and Saville’s practice in general remains unclear.

Jenny Saville, “Propped,” 1992

From the late ’90s onward, there’s a shift in Saville’s focus. While the gaze remains as surgical and dispassionate as ever, the scope frequently tightens to portraiture, with a new ferocity creeping into the palette. 1997’s Figure 11.23 is nothing short of terrifying. Its subject appears to be a victim of some horrific fire or accident, its skin burned to a deep, flinch-inducing crimson. Hair sticks out in scorched wisps, while haunted, desperate eyes seem to dare the viewer to both look and look away. Hung nearby, Stare (2004–05) further develops this theme of disfigurement. Based on a photograph taken from a medical textbook, the painting (later used as the cover art for the Manic Street Preachers’ 2009 album Journal for Plague Lovers) depicts a woman with a “port-wine stain” birthmark on her face, the paint built up in layers of scarlet and deep pinks that bleed into each other. This contrasts with the cold, aqueous tones of blue and green that wash through the portrait’s background, emphasizing the woman’s loneliness.

For Saville, mouths and eyes appear to operate much like what Roland Barthes called the punctum: the singular detail of an image that pierces the viewer. (That Saville works primarily from photographs only serves to emphasize this correspondence with Barthes’s trenchant 1980 study of photography, Camera Lucida.) 2009’s Witness depicts the figure’s mouth as a chaos of brushwork, gaping and violent as a wound. In 2019’s Self Portrait (after Rembrandt), a glossy, raw corner of paint on the artist’s lip makes it appear almost as if the flesh has been chipped off, exposing a painful and bright streak of vulnerability. Saville’s work frequently commingles a kind of tenderness with a sense of suffering, so that it’s impossible to know where one starts and the other ends; indeed, it can often feel as if her subjects (including herself) are being punished as much as glorified. Reverse (2002–03) captures the painter’s head, pressed up against glass like a medical specimen. The field of vision seems voyeuristically compressed and magnified, her mouth parted to show teeth in a way that somehow feels painfully close.

Jenny Saville, “Pieta I,” 2019-21

As “The Anatomy of Painting” goes on, more art historical references are pulled in, bolstering the titles of Saville’s paintings or seemingly lending intellectual import to the wall texts. Increasingly, however, they provide a sense that the works are no longer trusted to stand alone. The impact of the earlier paintings – which one often registers as a physical force – is replaced by the imprimatur of outside sources. Rosetta II (2005–06) is, according to the artist, intended to evoke “the classical idea of the mysticism of a blind person’s stare,” with Picasso’s La Celestina (1904) as a forebear. The result, both slickly painted and strangely uncanny, seems to pride itself more on its referential qualities, a tendency that only becomes more pronounced as the show progresses.

The mid-section of the exhibition focuses on many of the artist’s works exploring motherhood. It also marks a move away from oil paint, introducing charcoal and pastel. Study for Pentimenti IV (after Michelangelo’s Virgin and Child) (2011) is a palimpsest-like flurry of linework, dexterous and energetic, in which Saville cradles her naked child, who rests upon her pregnant stomach. We see the ghosts or after-impressions of other poses within the mark-making, as if capturing the motion of trying to pose with a restless toddler. Yet this study (along with neighboring versions) lacks the solidity of the preceding works. Aleppo (2017–18), its title a reference to the Syrian capital, under siege by Turkish forces during the years of the work’s creation, feels oddly weightless. Depicting an obscured figure carrying two children aloft, its softened hues of turquoise and red pastel convey a muting effect. Another charcoal and pastel work on canvas, 2019–21’s Pieta I, is in conversation with Michelangelo’s great sculpture The Deposition (1547–55). Yet its sober classicism represses any sense of ambivalence under the drawing’s smooth surface.

Jenny Saville, “Rosetta II,” 2005-06

The final room of the exhibition showcases Saville’s most recent works. Made from 2020 onward, they see her change tack once again, returning to close-up studies of the human face and injecting them with a bold, effervescent new palette. The canvases are overloaded with a sugar-rush confection of colors, from sizzling candy pinks to streaks of egg-yolk yellow to fizzing scribbles of magenta. These contemporary works also betray the influence of their era, their surfaces seeming to mimic the fractures and digital mediations of our screen-based reality.

In Stanza (2020–22), the visual plane seems disrupted, out of sync. The three sections of the subject’s head, described in oil and oil stick, appear slightly out of alignment, as if performing a technical glitch. Moreover, the recursiveness of this study (“pivoting between a portrait of painting and a painting of a head,” as Saville is quoted as describing it in the accompanying wall text) is emphasized by a painted fragment of another eye, seemingly superimposed next to the subject’s mouth. Virtual (2020) replicates this collage effect, while turning the entire head upside down in a kind of visual gimmick. (Saville has spoken in interviews of taking selfies which she then cuts up and reassembles as source material for her more recent works.)

Yet for all this experimentation, a repetition – even a shallowness – begins to assert itself in this later work. Saville’s tendency toward a certain kind of stylized effect, rather than amplifying her figuration, begins to offer gradually diminishing returns. It’s difficult to feel anything like the torrents of attraction and repulsion produced by those monumental early canvases, in whose presence one is made to feel so awe-struck. Now, the viewer is flattered into feeling they are “in” on Saville’s design, the nakedness of her earlier subjects superseded by bare proficiency. One marvels at the undeniable skill of the paintings’ execution, the sureness of their facility. Yet if they succeed as displays of finesse, they offer increasingly little beyond this. What happens when a careful scrutiny of surfaces hardens into a style, retreating into the merely skin-deep? In 2020’s Chasah, the painter herself appears as a small reflection in the subject’s eye. If the artist remains firmly present, her diminution is an object lesson indeed.

“Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting,” National Portrait Gallery, London, June 20– September 7, 2025.

Daniel Culpan is a writer based in London.

Image credit: 1 + 3: courtesy Gagosian, private collection; 2: courtesy Gagosian, the George Economou Collection; 4: courtesy the George Economou Collection; 5: courtesy Gagosian, private collection; all images © Jenny Saville, photos David Parry