ABSTRACTION, ACTIVISM, AND COLLECTIVE ENDEAVOR Daniel Sturgis on the Casablanca Art School at Tate St Ives

“The Casablanca School,” Tate St Ives, 2023, installation view

A huge photograph of the entrance to the Casablanca Art School (CAS) in 1968, decked out in brightly colored abstract wall hangings, opens the first museum exhibition in the UK dedicated to this radical art school, whose work is currently on view at Tate’s Cornish hub. The vibrant political optimism expressed in this photographic mural is visually startling after having walked through the permanent exhibition of tasteful British modernism, much of it produced locally in St Ives, which was an epicenter of British abstraction in the 1930s and ’40s. This exhibition on the Casablanca Art School reminds us that the language of abstraction is now often wrongly seen as non-political and detached from the urgencies of the day.

The Casablanca Art School developed out of the École des Beaux-Arts de Casablanca, which was set up by French colonial powers in the 1920s and followed the tradition of French academies, though the system in Morocco segregated students by both gender and ethnicity. In 1962, six years after Moroccan independence, the artist Farid Belkahia, who had studied in Paris and Prague, became the school’s director at the age of 28. He radically reimagined the school’s purpose, dismantling much of the old academic model. As a result, the CAS became the heart of a vibrant postcolonial avant-garde invested in developing its unique visual culture.

Farid Belkahia, “Cuba Si,” 1961

Curated by Zamân Books & Curating, a Paris-based research and publishing project that focuses on celebrating Arab, African, and Asian transcultural artistic heritages, [1] the show brings together the work of 22 artists associated with the CAS, alongside a wonderful collection of archival materials and photographs. These are drawn from an imminent Zamân Books publication on the Casablanca Art School’s archives, which has been edited by researchers Fatima-Zahra Lakrissa and Maud Houssais and will contain key texts from the leading artists and theorists associated with the school. It is a shame that this exhibition did not coincide with the publication, as it may have helped counter the lack of in-depth – and especially biographical – information in the galleries. Earlier iterations of Zamân Books’ presentation of the CAS included far more contextual information: there was, for example, a display on the school as part of the “Bauhaus Imaginista” exhibition in Berlin in 2019 that forefronted the interconnections between the Casablanca Art School’s pedagogy and that of the Bauhaus through the schools’ desire to interconnect art fully with society. [2] The artist Mohamed Melehi, known for his bold, decorative, and hard-edged paintings and central to the CAS’s history, was the focus of the show “New Waves: Mohamed Melehi and the Casablanca Art School” initially presented at the Mosaic Rooms in London the same year. [3]

Melehi was, along with the painter Mohammed Chabâa, hired by the CAS’s director Belkahia as a teacher in the mid 1960s, and through the Tate St Ives’s exhibition we can trace the development of this trio’s work. They created a shared visual language that was in dialogue with Western painting and the decorative iconography of traditional Moroccan arts, such as the design of Amazigh rugs and jewelry, or the marvelous wooden painted ceilings of the region’s rural mosques. In the first room we are introduced to their collective practice through a selection of early paintings. Belkahia, who was conversant in trends in Western painting through both his studies and his father’s art collection, initially employed a raw expressive figurative language. His painting of a figure with arms raised, Cuba Si (1961), openly proclaims revolutionary intentions through its title and art brut sensibilities. As the exhibition progresses, we see Belkahia move away from painting and figuration, using wood, plastics, and animal skins in a more diagrammatic and abstract language instead. This development is indebted to Chabâa’s and Melehi’s influence. Both artists are introduced working with bright flat acrylic painting from the start, but as the exhibition proceeds chronologically, we see Melehi’s material choices expand and become more industrial, with a high-octane palette, sprayed color, and cellulose paint. Chabâa meanwhile endows the making of his work with direct political intent as he moves between painting and graphic design, making posters which he described as paintings “accessible for all.” [4] He also codesigned with Melehi (and eventually took sole design responsibility for) the journal Souffles, with which they aimed to decolonize Moroccan art and culture through poetry, critique, and the bold graphic schema of waves, zig-zags, and ziggurats – forms which also populate both artists’ paintings. Within the exhibition we see designs championing Palestinian, Angolan, and Pan-Arab solidarity. The publication of Souffles eventually led to Chabâa’s imprisonment in 1972 for being a Marxist activist.

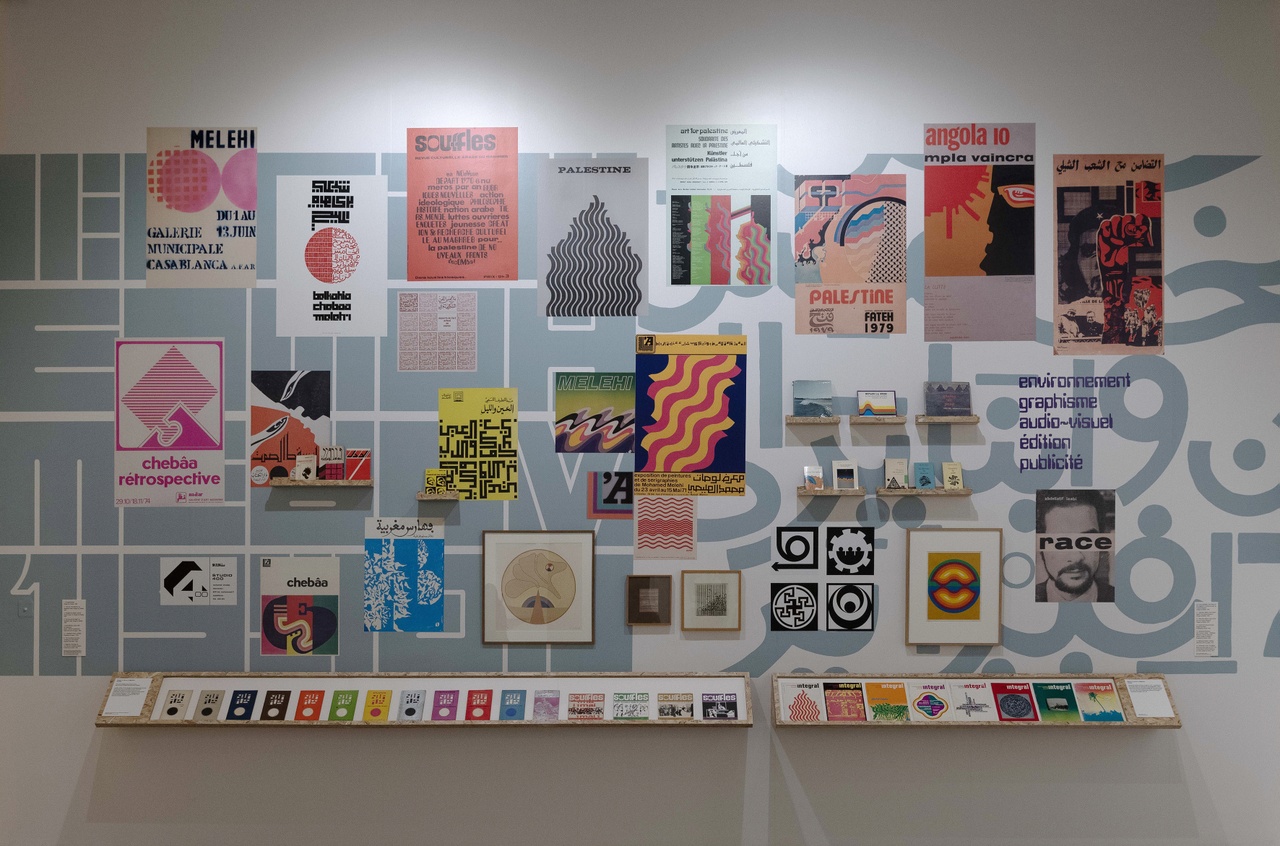

“The Casablanca School,” Tate St Ives, 2023, installation view

In January 1966, the Casablanca trio rejected showing in the traditional Academy exhibitions, and instead presented their work at the Théâtre Mohammed V in Rabat. It is the earliest example of how the CAS artists sought out new spaces that were less institutionalized and more public to exhibit in opposition to colonial norms. Just prior to that exhibition’s opening, Chabâa had published the manifesto “On the Concept of Painting and the Plastic Language.” [5] It is alas not available in Tate’s galleries. In the text, he proclaims how painting must distance itself from European modes of representation and embrace Arab and African traditions to avoid exoticism and instead demonstrate a “trace of Moroccan authenticity.” [6] This desire for painting to reengage with African and Arab vernacular traditions so as to build a corresponding aesthetic was the guiding force in the newly imagined Casablanca Art School.

Melehi and Chabâa knew each other by having studied together at the National Institute of Fine Arts in Tetouan and, like Belkahia, they had travelled and studied internationally. Both had worked in Rome in the late 1950s, and it was through conversations with artists such as Alberto Burri and Jannis Kounellis that Melehi states he found what he calls his “local identity” – his ability, as a North African contemporary painter, to develop paintings that materially and conceptually connect to Moroccan craft traditions and Amazigh culture. [7] Although one can assume that the interconnections with European avant-garde artists must have been formative for Melehi and Chabâa, they are not explained in the exhibition, nor is the fact that Melehi also drew inspiration from contemporary New York School painting. The earliest of his paintings on view, Minneapolis (1963), points to his time and experiences in the United States. It is important to understand that in the early 1960s, Melehi had studied at Columbia University on a Rockefeller Foundation scholarship and gone on to set up a studio alongside New York painters, such as Jim Dine. During that time, Melehi fully embraced hard-edge abstraction and first melded his use of increasingly bold colors with the iconography of his cultural heritage. The lack of these contextualizations is disappointing, given that previous iterations of Zamân Books’ curation on the CAS had provided them.

What is explained through artifacts and some wonderfully evocative photographs of classes and exhibitions in the school is how Belkahia invited the Dutch anthropologist Bert Flint and the Italian art historian Toni Mariani to join the CAS. One photograph shows a chicly dressed Mariani lecturing students in front a chalk board with a large, hand-drawn outline of the African continent on it. Together, this young internationally connected faculty merged interdisciplinary ideas associated with the Bauhaus, such as arts centrality, to society at large with deep research into local Amazigh and Arab architectural and archaeological heritage. Students worked collectively, going on field trips and studying traditional styles of calligraphy, jewelry, pottery, and weaving to create new works and a transnational understanding of what a Moroccan form of modernism might look like for a newly independent postcolonial country.

Asilah Cultural Festival, mural by Miloud Labied, 1978

Instead of drawing and painting from plaster casts of Greek and Roman antiquity, which had been the norm in the beaux-arts school, Flint encouraged students to draw from Arab and African textiles and jewelry, seeing his purpose as “questioning the teaching methods used in Europe by attributing an aesthetic value to the traditional arts of Morocco.” [8] The genuineness of Flint’s enthusiasm about such material culture and a pedagogy that stressed the interconnections between art and crafts is evident in this exhibition, but the complexity of introducing a European anthropological model is not addressed. A wonderful Amazigh rug and a carved painted wooden pillar from an unspecified building in Marrakesh have been brought into the galleries. Both exhibits can be seen in dialogue with individual works that visually relate to them, such as Mohamed Hamidi’s beautifully reduced painting Composition (1971), depicting a single floating yellow form on a bright orange ground, or Mohamed Ataallah’s more colorful, vibrant, and celebratory paintings of curving bands or contours of rainbow-like colors.

Both Hamidi and Ataallah, who were also professors at the CAS, took part with Belkahia, Melehi, Chabâa, and the painter Mustapha Hafid in “Presence Plastique” (1969), an important exhibition initially presented at Place Jemaa el-Fna, Marrakech. In its content and its display, “Presence Plastique” was a manifesto exhibition with all the paintings displayed outside as a way of protest and to engage more directly with everyday audiences. Films and archival photographs from the exhibition are projected onto Tate St Ives’s walls. The documentation of the fragile paintings with their crisp surfaces, exhibited on fences and temporary exhibition structures in the middle of a busy town square looks radical today. “Presence Plastique” exemplified the CAS’s desire to make art truly public and to act as a form of criticism of the dominant state-run systems of artistic support in Morocco. As such, it provided a stark contrast to the majority of exhibitions of the time, such as the state-organized “Salon du Printemps,” which still categorized and exhibited Moroccan painters, as opposed to European artists in Morocco, as “naïve.”

The curatorial strategy behind “Presence Plastique” of exhibiting bold formalist paintings imbued with latent signifiers from Arab and Amazigh culture in the public realm led to two related consequences: Firstly, artists associated with the CAS began to create public artworks for new hotels, banks, and civic buildings. At Tate St Ives, there is a gallery dedicated to the architectural firm Faraoui & de Mazieres, where we can see how Melehi and Chabâa as well as the Sicilian artist Carla Accardi designed site-specific artworks that were fully integrated into these new modernist spaces. Accardi had strong connections with the CAS group; she knew Melehi and Mariani from Rome, and was then in a relationship with Hamdi. In 1978, arguably propelled by the ethos of “Presence Plastique,” Melehi and the local politician Mohamed Benaïssa founded the Cultural Moussem of Asilah. For the festival, which included live art and musical performances, the walls of this Mediterranean town were conceived as a canvas. In the final gallery at St Ives, photographs of the artists painting their bold abstract designs directly onto Asilah’s traditional white buildings are displayed alongside later works that emerged from the CAS. The festival, which continues to this day, is rightly positioned as a very real and thriving legacy of the Casablanca Art School. On reflection though, the greatest merit of the CAS and its rich legacy lies not only in the wonderfully vibrant and life-affirming paintings and artifacts that were produced by artists associated with the school, but also in reminding us of the important role collective activism played in forming a unique understanding of a politics of abstraction.

“The Casablanca Art School,” Tate St Ives, May 27, 2023–January 14, 2024.

Daniel Sturgis is an artist and professor of painting at the University of the Arts London.

Image credit: 1. + 3. © Tate, photo Seraphina Neville; 2. © Foundation Farid Belkahia; 4. © M. Melehi archives/estate, photo Mohamed Melehi

Notes

| [1] | The exhibition was specifically curated by Morad Montazami and Madeleine de Colnet from Zamân Books & Curating in partnership with Anne Barlow and Giles Jackson from Tate St Ives. |

| [2] | The relationship between the Casablanca Art School and the Bauhaus was theoretical and pedagogical – with inspiration being taken from Walter Gropius’s interests in the interconnection of art and society, initially through craft traditions and then technological innovation – as well as aesthetic, with many of the CAS artists inspired directly by the abstract idioms of the Bauhaus painters such as Klee and Kandinsky. See “Bauhaus Imaginista: Learning from, Rabat,” 2018, Bauhaus Imaginista. |

| [3] | “New Waves: Mohamed Melehi and the Casablanca Art School,” Mosaic Rooms, London, April 12–June 22, 2019. |

| [4] | Gallery wall text. |

| [5] | Mohammed Chabâa, “On the Concept of Painting and the Plastic Language” (1966), trans. Kareem James Abu Zeid, reprinted in Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, ed. Anneka Lenssen, Sarah Rogers, and Nada Shabout (New York: MoMA, 2019), available online. |

| [6] | Ibid. |

| [7] | Oliver Basciano, “Mohamed Melehi Obituary,” Guardian, November 20, 2020. |

| [8] | Bert Flint, “How My Understanding of Moroccan Culture Has Evolved” [1957], reprinted in Bert Flint, exh. brochure (Marrakech: Fondation Jardin Majorelle, Musée Yves Saint Laurent Marrakech, 2021), 4–5. |