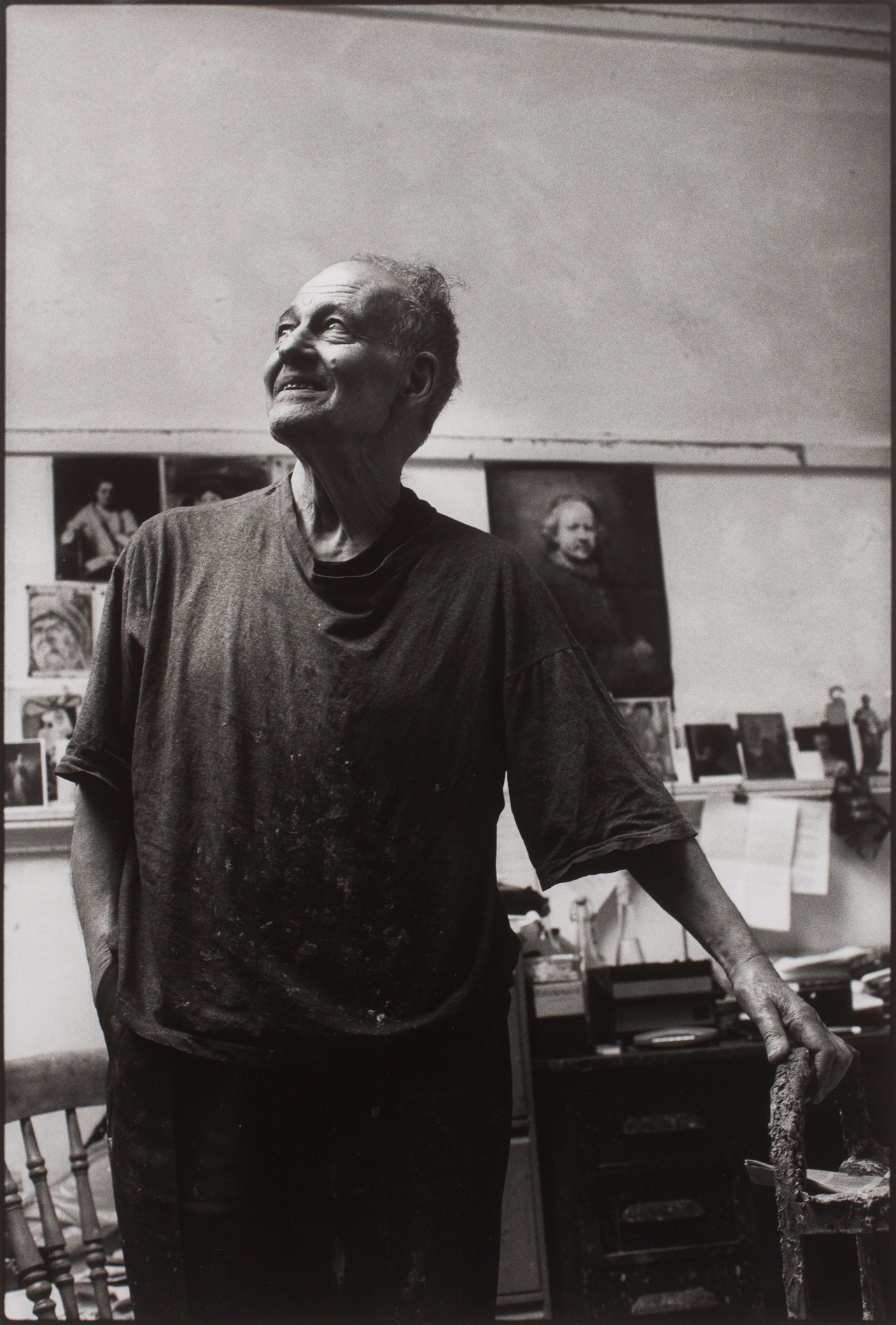

FRANK AUERBACH (1931–2024) By Invar-Torre Hollaus

Frank Auerbach in his studio, 2015

In a career spanning seven decades, Frank Auerbach became known for his lively portraits of a handful of people close to him and for vibrant cityscapes from the immediate vicinity of his studio in Camden, North London. He was also known for his reclusive lifestyle, the intensity of his working method, and the strict schedule according to which he drew and painted his models. When it was not possible for him to meet his sitters during the Covid-19 pandemic, he resorted to his own likeness. These self-portraits are surprising in their life-affirming and jaunty choice of colors, as well as in their awareness of the evanescence of life: Advanced age and physical decay are clearly visible and perceptible in many of these late paintings. In them, an uncompromisingly lived life comes to a dignified conclusion: Auerbach subordinated everything to his painting.

Auerbach was born in Berlin on April 29, 1931. He grew up in a liberal, assimilated Jewish family with an affinity for the arts; the literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki was one of his cousins. Shortly before his eighth birthday, his parents were able to send him by ship from Hamburg to England, thus saving him from the racist and antisemitic reprisals of the National Socialists. The writer Iris Origo acted as guarantor for him and five other Jewish children. The farewell from his family was forever. Auerbach’s parents were deported to Auschwitz in March 1943 and murdered there. [1]

In 1947, Auerbach became a British citizen and settled in London. He hardly ever left the city again. From 1947 to 1955, he studied painting and drawing at Saint Martin’s School of Art, the Royal College of Art, and Borough Polytechnic, where his lessons with David Bomberg, together with his student friend Leon Kossoff, left a lasting impression on him. Especially Bomberg’s idea of the “spirit in the mass,” aiming to capture a sense of structure and immanence through the painter’s thorough engagement with the physical world, based on the further development of Paul Cézanne’s painterly legacy to rid the subject of extraneous details through vigorous brushwork, decisively shaped both Auerbach’s and Kossoff’s vision of painting. At the Royal College of Art, Auerbach met Julia Wolstenholme, whom he married in 1958, only to separate from her soon afterwards; their son, Jake, was also born the same year. [2] The family reunited in 1976, and Julia became Auerbach’s most important model until her death in January 2024. In 1954, Auerbach took over the aforementioned studio in Camden from Kossoff, where he worked until the end of his life.

In 1956, the art dealer Helen Lessore included the young Auerbach in the progressive program of her Beaux Arts Gallery, which was one of London’s key galleries of the postwar period, along with Erica Brausen’s Hanover Gallery. From 1964, Auerbach was exclusively represented by the international gallery Marlborough Fine Art, only changing to Frankie Rossi Art Projects in 2023. By the early 1960s, he was highly regarded by then already famous fellow artists such as Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, and he received much praise and recognition from various influential critics, including David Sylvester, John Berger, and Michael Podro. In his review, Sylvester welcomed Auerbach’s first exhibition at the Beaux Arts Gallery as the “the most exciting and impressive first one-man show by an English painter since Francis Bacon in 1949.” [3] Nevertheless, it would take until 1978 for Auerbach’s artistic breakthrough, when Catherine Lampert curated his first institutional solo exhibition, at the Hayward Gallery in London. [4] International recognition came eight years later, when Auerbach represented Great Britain at the 1986 Venice Biennale and was awarded the Golden Lion alongside Sigmar Polke. Auerbach is associated with the “School of London,” a term invented by fellow artist Ronald B. Kitaj in 1976 describing a group of London-based artists who were working with figurative painting and especially the human form in response to postwar abstract art. The core group included the aforementioned Bacon, Freud, Kossoff, Auerbach, Kitaj, and Michael Andrews. However, the alleged group members, because of their stylistic differences and autonomous working methods, did not subscribe to this homogenizing notion.

Characteristic of Auerbach’s early work is a thick, impasto, multilayered paint application, as well as a reduced tonal range of mostly browns, ochres, yellows, and reds. The surface of the motifs is built up and relief-like, evoking a visually and physically dynamic tactile texture. From the mid-1960s, his palette significantly changed and brightened up, as this was also when he was able to afford more expensive colors. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, he decisively changed his technique. Instead of successively adding countless layers of paint, he started scraping off the material after each session, beginning anew on those remnants in the next. What remained in this process is a palimpsest of traces of color and of the composition, which are interwoven and condensed into an increasingly coherent representation until, ultimately, the image is completed in one final session.

Auerbach was considered a workaholic who painted tirelessly from dawn to dusk, almost 365 days a year. Photographs of his studio show an orderly chaos with a paint-encrusted easel, painting utensils, and a floor from which remnants of paint grow upward like stalagmites. His concentrated, slow, and painstaking way of working meant he took months, sometimes years, to complete a picture. [5] This critical, doubting attitude recalls Cézanne’s countless attempts to finish the Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1899); or Pablo Picasso’s nearly one hundred sessions with Gertrude Stein, until he stopped working on her portrait in 1906; or Alberto Giacometti reworking the same image over and over again to find an appropriate depiction of the energy of his sitters – all three artists being key references for Auerbach. In addition to his wife, Julia, and his son, Jake, the other people who sat for him patiently, week after week for 20, and some for over more than 40, years – he called them “persistent sitters” – were much more than just that: they became lifelong friends.

The many years of lived experience with this other person, the striving for depth and truthfulness, allowed Auerbach to reduce the motif to its essence and to abbreviate it. Even in traces of scraped-off layers of color, all these experiences still resonate like echoes. This working process led neither to schematized rigidity nor to a faithful reproduction, but to a dynamization of each individual brushstroke. Despite the emotional closeness that Auerbach associated with their respective people and places, the pictures are free of nostalgia, romanticizing, or voyeuristic kitsch.

This certainly unusual way of life was repeatedly reduced to cliché in reviews. Anyone who had the privilege of getting to know Frank Auerbach encountered a person who was intellectually and empathetically extremely alert, without airs and graces, and who was warm, humorous, and generous; he had an immense knowledge of art history, engaged in lively discussions, and could recite entire poems off the cuff.

Auerbach is still regarded as an artist’s artist: highly esteemed by many – stylistically very different – artists, including Georg Baselitz, Cecily Brown, Peter Doig, Glenn Brown, Sean Scully, Celia Paul, Helmut Federle, Eberhard Havekost, and Jutta Koether but still overlooked by large sections of art critics and the public. [6] This is particularly true in his country of birth, Germany, where he was long denied recognition. Auerbach was introduced to the German public for the first time only in 1986–87, when the Kunstverein in Hamburg and the Museum Folkwang in Essen took over his Biennale presentation in substantial parts. However, almost 30 more years were to pass before his next institutional solo exhibition in Germany, in 2015, when the Kunstmuseum Bonn co-organized with Tate Britain the most comprehensive and highly acclaimed retrospective on Auerbach to date, comprising both his portraits and his London cityscapes from all periods. In 2018, Frankfurt’s Städel presented a finely curated double exhibition of etchings and drawings by Auerbach and Freud. His native city of Berlin has so far remained a blank spot over all these years, yet Galerie Michael Werner is now making a start to rectify this, as it will honor Frank Auerbach posthumously with an exhibition in May of this year. [7]

Invar-Torre Hollaus is an art historian. Since 2010, he is a lecturer at the Institute of Digital Communication Environments IDCE at the Hochschule für Gestaltung und Kunst (FHNW) in Basel. Author of numerous publications on contemporary artists including an extensive monograph on Frank Auerbach (Piet Meyer Verlag: Bern/Vienna 2016).

Image credit: © Nicola Bensley, courtesy of Piano Nobile

Notes

| [1] | At Güntzelstraße 49 in the Berlin district of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, Stolpersteine commemorate the fate of his parents; see here. |

| [2] | Jake Auerbach has made a name for through by his subtle documentaries on various artists, including on Frank Auerbach: Frank Auerbach: To the Studio (2001) and Frank (2016). |

| [3] | David Sylvester, “Young British Artists,” The Listener, January 12, 1956, 64. |

| [4] | Catherine Lampert sat for Auerbach on an almost weekly basis from 1978 to 2024, and she is the most important curator and author of key monographs on Frank Auerbach. Recommended reading: Catherine Lampert, Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting (Thames and Hudson, 2015) and, edited together with Mark Hallett, Frank Auerbach: Drawings of People (Yale University Press, 2023). |

| [5] | His oeuvre is correspondingly small. The catalogue raisonné of paintings and large-format drawings, updated in 2022, lists 1,236 works, see: William Feaver, Frank Auerbach (Rizzoli, 2022, 2nd revised edition). |

| [6] | Koether authored a very personal obituary to Auerbach in this magazine; see Jutta Koether, “Frank Auerbach (1931–2024)”, TEXTE ZUR KUNST, January 27, 2025. |

| [7] | Instructive in this regard is Cornelius Lüttke, “Vom Hochheben, Fallenlassen, Vergessen und Ehren,” Kunstzeitung, no. 294 (August/September 2021): 13. |