THERE WAS JUST THE MAYHEM THAT ENSUED IN REALITY Franziska Aigner in conversation with Paul Poet on “Bitte liebt Österreich” by Christoph Schlingensief

Paul Poet, “Ausländer raus! Schlingensiefs Container,” 2002

FRANZISKA AIGNER: Hi Paul! Europe and the world at large are currently undergoing a massive shift toward the right, toward populism, and a renewed kind of fascism. In many ways, the political climate we’re experiencing now mirrors the atmosphere in Austria in 2000 – when far-right politics entered the mainstream under the guise of democratic legitimacy. Before diving into the performance and your film about it, could you begin by recounting for us the political climate in which you found yourself in the year 2000?

PAUL POET: Politics was in a complete frenzy in Austria back then. Nowadays, we seem much more accustomed, frighteningly, to there being Nazis and criminals in various European governments. But in the year 2000, Austria was the first country in the European Union that had an extreme right-wing party in government in postwar Europe. The Freiheitliche Partei Österreich (FPÖ) derived directly from Austria’s National Socialist past and had retained its ideology. The Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) was power hungry, yet nobody imagined that they would actually form a coalition with the FPÖ, because of the extreme, blatant xenophobia that the FPÖ represented. After the elections, some European countries stopped their diplomatic and financial exchanges with Austria. The media was frightened, while politicians kept a stiff upper lip and said this is an elected government – as they always say. They didn’t give a shit. Following the elections and surrounding the coalition talks, there was a big uproar in the public, problematizing the FPÖ’s newfound official status after decades of being in the opposition. When the government was sworn in a few months later, there was a second uproar. The prospective government had to walk to the ceremony through an underground tunnel because a huge demonstration was blocking its path. But after a while it became clear that the demonstrations didn’t have the necessary efficiency to actually protest the government or the political issues at stake anymore. I was quite disillusioned.

AIGNER: How did the project with Christoph come about?

POET: Luc Bondy, the director of the Wiener Festwochen, essentially invited Christoph to do something during the festival that would protest the right-wing shift in Austria. First, Christoph had wanted to do a project called Der kapital-faschistische Oscar, an Oscar award ceremony for the biggest accomplishment of the military-industrial complex. He wanted to stage the celebration at the opera, but it was too expensive, and Ioan Holender, the head of the opera, was completely offended by the idea. Bondy told Christoph: You can still do something, but we have a very limited budget and can’t include you in the official catalog. So whatever we were gonna do was gonna be a quasi-underground project of the Festwochen. In the end, there wasn’t even an official announcement of the project. Christoph’s second proposal was to put up a Big Brother container in the city and have the Austrian public vote asylum seekers in and out of the container and thereby out of the country. He had been asked a few weeks prior to the whole thing by the Süddeutsche Zeitung, a Bavarian newspaper, to write something on the Big Brother phenomenon – which had initially passed him by because he was into Grindhouse underground extreme stuff rather than mainstream pop culture formats. But eventually he looked at this whole thing of living in the public and had this question: What would a concentration camp look like in the 21st century? And his answer was, like a Big Brother container, as in a freight container. Bondy insisted that there was no official mention of the concentration camp aesthetic, but it was obvious to everyone, of course.

AIGNER: Mounted on top of the container was a big banner that read “Ausländer Raus” (Foreigners Out), which articulated the fascist vision of a cleansed nation as promised to the Austrian people by the FPÖ during the election. That same slogan would also eventually provide the name for your documentary. The container itself was positioned right in front of the Staatsoper, the national opera in Vienna.

POET: That area of Vienna is a very in-your-face tourist spot. After trying everything in its power to cancel the project altogether, the magistrate of the city of Vienna itself proposed to put the container there. They probably thought that the container would be invisible there with all the tourists and Mozart impersonators swirling around. But they were very, very wrong, luckily.

AIGNER: You built up the website and the online voting system?

POET: Yes, I set up the homepage called www.auslanderraus.at and was responsible for both its aesthetic and the voting system. We had invited real asylum seekers from all over Austria to take part in the action. They were officially hired as actors impersonating asylum seekers, which was ultimately an illegal act by the Wiener Festwochen. We didn’t know how, once inside the container, the asylum seekers would cope with everything. There were fights inside the container, but people also invaded the container from the outside and there were people screaming at each other in front of the container all day every day. But I have to say, the asylum seekers seemed to have the most fun of all of us; they knew violence, they knew mistreatment. Sitting at the window, looking out and seeing others go berserk seems to have been fun for some of them. But for some, the pressure was too much, and we manipulated the voting system so that they could leave. There was a lot of pressure on all of us, but it was also a lot of fun: a sleepless week where we didn’t know if we were going to persist for more than one day.

AIGNER: The homepage allowed people all over the world to engage in this despicable process of voting people in and out of the container; by doing so, it enacted, in a very direct manner, the xenophobic fantasy that got the FPÖ elected in the first place. The real-life consequence was, of course, that whoever had to leave the container would be deported from Austria. And whoever was left in the end was going to get the right to stay. We can see in your documentary that the first two days of the action were relatively peaceful, especially in retrospect, considering what happened at the end.

POET: People looked at the action as high art at first. The Wiener Festwochen are a very posh, established art festival that is both connected with and financed by the state. But soon, whether it was the right, the left or the political middle class, everyone freaked out. And even more so after two days, which was when the media coverage began. Wolfgang Schüssel, Austria’s conservative chancellor at the time, personally told Bondy to shut the action down. But also the SPÖ, Austria’s social democratic party, told us to shut it down. They thought it was ugly and an affront to Austria. Bondy eventually went to lunch with Schüssel and blackmailed him into tolerating the event by asking him how to respond to an interview request for the front page of Le Monde if the action were to be cancelled. So it all slowly became more and more interactive.

Paul Poet, “Ausländer raus! Schlingensiefs Container,” 2002

AIGNER: What happened inside and in front of the container influenced Austrian political life on a day-to-day level. I remember reading about it all in the newspaper as a teenager at my mum’s house in Salzburg. Why, do you think, did people get so invested and upset about the container?

POET: The work was a public vessel, an open art system that mirrored society, including all its ills and its ugliness. In a way, the project did provide a safe space, because it’s still art that you can play around in. But at the same time, in order to participate in the performance, you were forced to reflect upon yourself and confront yourself with your own hatred. The work asked you who you really are, who you are politically. Christoph called it a social plastic. A social plastic forces you to confront yourself with yourself in order to, hopefully, change your ways. It could only have this impact because it was not a dogmatic work of propaganda. I mean, the bottom line of the action was clear: it was against xenophobia, against Ausländerhass, against right-wing aesthetics of hate. But at the same time, it was equally in opposition to the Green Party, who in some ways might be closer to Christoph’s own views, as it was in opposition to the FPÖ. There was this great openness that put everyone in a complete frenzy and fear about what would happen. Even 25 years later, the action is still a battleground; some are still afraid of it, how it unraveled, how it didn’t have a clear outcome. Politics loves it if you make a statement, if people can say yes or no. But here, there was never a clear yes or no. There was just the mayhem that ensued in reality. The nickname I gave the film afterwards was “democracy the hard way,” because you really had to go out there and interact. Nobody could know in advance where it would all lead.

AIGNER: What did this mean for you on an artistic level? How did you prepare the day-to-day proceedings of the action?

POET: There was no planning. I mean, we had prepared rituals and texts and invited different guests to speak at the container each day. But I think the important thing was really to let it loose. That’s what made it one of Christoph’s really important pieces, because he abandoned all artistic control, in a similar way to Chance 2000. Both works are so precious and unique because he let them loose. After Vienna, he asked me to do a second film with him, and I was following him for some years during the early years of Church of Fear (Die Kirche der Angst). He was feeling desperate, because he said he could never top it. Three days into the container, he was so confused with himself, he didn’t know how to control the container anymore. He felt the importance of losing control, of accepting that the proceedings of the action couldn’t be prepared and anticipated by anyone, even himself. It was really a democratic piece of art. There was no artistic genius pulling the strings. We had games and rules and tried to keep them in order, but at the same time, what really happened there, the explosion of political discourse and fights and the way it turned out worldwide through the media and the website was completely out of our hands. It was so beyond us – beyond our grasp.

AIGNER: Within the radical democratic openness of the action and the public space enacted by it, there was nevertheless one group who did not actively participate in this public forum, be it before, during, or after the action. And that were the asylum seekers, larping as performers impersonating asylum seekers. How did you conceive of this asymmetry?

POET: There were in fact a lot of asylum seekers, migrants, and foreigners within the crowd, participating in the quarrels. The ones in the container were intentionally not given a voice, in order to emphasize them as projection pieces on which the audience in front of the container could try out their differing levels of xenophobia. They had a relaxed time in the safety inside the container watching all these blood-red Caucasian heads going at each other’s throats. The whole project wouldn’t have worked if we had followed the usual white guilt narrative of click empathy for the fugitive, itself a form of privileged xenophobia, that smothers instead of beats up, but essentially just cares for itself, not the other. As Christoph says in my movie, we didn’t do Amnesty International.

AIGNER: In one of your interviews with Schlingensief in your documentary, he talks about how he has little understanding for the Austrian peace activists and that their image ought to be disturbed. He called the work of the container a Bildstörungsmaschine, an image disruption machine. What was your criticism of the Austrian left back then?

POET: After the election, Donnerstagsdemonstrationen were organized every week. Over time the demonstrations became something of a narcissistic exercise with no real impact on politics. There wasn’t any real interest or investment in political action. Both Christoph and I were disillusioned that this mode of protest would go anywhere. I mean, it’s always good if people go on the street to protest something. But it seemed to me that there wasn’t any interest or investment in real political discourse and action. So the image disruption of the container was about the production of a polarized image of both the left and the right while opening a real political discourse, a political exchange.

AIGNER: In 2000, the Wiener Festwochen took place in June, just three months into the new government’s legislative period. How did the fatigued political left respond to your image disruption machine?

POET: You mean the demonstration that destroyed the container for a short time?

AIGNER: Yes, one might imagine that the harshest backlash against the container would have come from the right, but I understand that wasn’t the case …

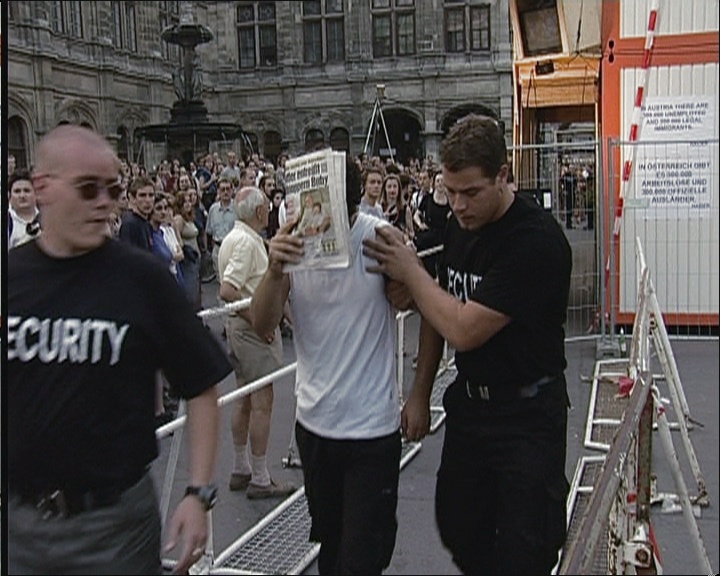

POET: Well, two nights earlier, some Nazi skinheads had already waited for us in front of the container. In fact, Nazi skins invaded the place twice. There were also acid attacks and people breaking into the container at night with knives. Everyone hated the project, the government, the officials, but also the police, who fully ignored everything happening at the container. Thank god we had our own security that worked. So it’s important to say that most of the appreciative audience that assembled in front of the container every day was from the left. But you are right. We had invited the Donnerstagsdemonstrationen to come and speak in front of the container and voice their side. But they didn’t want to participate because they saw it as art rather than a political action. And so, on Thursday of that week, when the weekly demonstration passed by the container, they got into this frenzy. The demonstrators climbed up on the container, nearly causing it to collapse. They set the banners on fire and wanted to free the asylum seekers as a statement, to transform the art piece back into a real political statement. The tricky thing was of course that all the asylum seekers were actual illegal aliens. And the moment the police would have gotten them, they would have been jailed and deported immediately. We had to evacuate everyone to a hotel nearby in order to avoid arrest. Basically, the demonstration tore the whole thing apart and Christoph eventually handed the container to the demonstrators in an act of capitulation and officially declared the art piece to be over. Then we went out for a drink and to bed. But at seven or eight in the morning, Christoph got up and said that he can’t keep this clean picture for the left. So he went back to the container, invited the asylum seekers to return, and we kept going for the rest of the week as planned.

AIGNER: The Austrian right wing is known for engaging with the public in a very direct and impactful manner. But after a couple of days, there were daily public assemblies in front of the container, giant demonstrations, and Schlingensief went on Austrian national TV during the evening news to publicly debate with local and national politicians. In a matter of a few days, the action became the focus of massive media coverage and public attention. How did the right respond?

POET: The two government parties, the FPÖ and the ÖVP, were invited to the container, but they never showed up and instead tried to shut it down by all means available to them. FPÖ politicians were open to being interviewed for my film afterwards – Jörg Haider and Peter Westenthaler, of all people. I guess they felt more secure to comment on the project in retrospect, but during the action itself, they would have been too anxious to become the clowns of the whole show. At the same time, I know just how important the action was and is for the FPÖ. They envied what we were doing, because they perceived it as a very successful manipulation of the public. They didn’t see the interactive or enlightening elements of the whole thing, but only how the action transfixed and engaged the public. I know that people like Martin Sellner from the Identitäre Bewegung Österreich or Johann Gudenus from the FPÖ studied my film in order to learn from the action and use it in a propagandistic way under different circumstances. It’s frightening. If you watch the neo-fascist movements of the past 20 to 30 years, they’ve all clearly studied left-wing art and subcultures in order to claim them. A piece of art is never innocent; you have to keep opening it up and severing any ties to political manipulation and parties using it as propaganda. So the right was, and still is, certainly there, and they were watching, but they would never have said that “Ausländer Raus” was a cool thing. And they are still trying to nourish themselves from it and take notes on how to use it at a later point.

Paul Poet, “Ausländer raus! Schlingensiefs Container,” 2002

AIGNER: How did the action end, how did it all end?

POET: After this fateful Thursday demonstration, the last day was more like: “Whoa, we lived through this.” Even if there were screams and it was violent to a degree, in the end, both the right and the left seemed to have appreciated going back to the roots of democracy, going to a square and getting at each other’s throats. There was dialogue.

AIGNER: Following the massive opposition and resistance to the performance from all sides, was your documentary film about the performance met with equal resistance?

POET: We tried to apply for funding for the film with a number of established production companies, but we were completely shut out. Apparently, the Austrian minister of art and culture at the time told the federal funding jury not to allocate any funding to our film. He walked into the meeting and addressed the jury directly. We had to do the film with almost no money. Christoph and I wanted to make another film later on, but we had no chance of getting funding for it either.

AIGNER: Both the action and your film ask a question of the art of assembly, of how something like parrhesia – of speaking truth to power – is possible in the present. The action was remarkable in how it brought about a temporary yet concrete political forum that could tolerate such a great deal of pressure and criticism.

POET: When I presented the film at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2014, it was really a shock to me. The basic reaction of this leftist intellectual elite of New York that was watching the film together with me was that if this had happened in New York, we would have been either shut down, jailed or shot within two days. I realized just how much the times have changed and how much the possibility of doing political art has changed. There have been several artistic projects that tried to learn from the container. Most obviously Das Zentrum für Politische Schönheit (The Center for Political Beauty). But they weren’t working on an open, democratic piece of art in the sense that no one knew what would happen. It’s important for the enlightening effect of political work that people work on themselves as if it were public therapy. But what’s healing is not the intention of the artist. Or maybe I should rather call it an exorcism or something like that. It’s up to the individual who participates in the work to find out about themselves. It’s about engaging in an interaction, a real interaction with the public, be it fun, be it thoughtful, be it excruciating – that doesn’t matter.

Paul Poet was initially an organizer, DJ, and punk singer in the Viennese underground scene. It was there that he met Christoph Schlingensief, with whom he collaborated on the performance project Bitte liebt Österreich (Please love Austria). From the filmed material of that project, he later made his first feature film as a director, Foreigners Out! Schlingensief’s Container (2002). Poet is currently working on, among several other projects, a filmic adaptation of Der Minusmann for the production company of Ulrich Seidl; the film tells the life story of the Viennese criminal Heinz Sobota. Poet’s most recent cinema release, the hybrid feature Der Soldat Monika (2024), is a genre-breaking biographical portrait of Monika Donner, an elite transsexual soldier, leading figure for gender rights, and book author celebrated by the political far right.

Franziska Aigner works at the intersection of performance, music, and philosophy. After studying at P.A.R.T.S., the school for choreography and dance in Brussels directed by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, she worked with Anne Imhof on the performances Deal, Rage, Angst and Faust (awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale 2017) and Natures Mortes, as well as performing for William Forsythe, Mette Ingvartsen, Alexandra Bachzetsis, Holly Herndon and others. Her own works have been shown at Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Brussels, Die Liste, Basel, Theatre de la Bastille, Paris,The Place, London, brut, Vienna, HAU, Berlin etc. She performs her solo music project (cello, vocals and electronics) under the name FRANKIE, with her first solo EP STYX released in 2022, followed by HEAVEN/HELL in 2023. She completed her PhD in philosophy at the CRMEP, Kingston University London, in 2020 and is currently a lecturer in philosophy at the New Centre of Research and Practice, teaching seminars on Modern European philosophy and philosophy of technology. Her monograph on Kant and technics was published with Bloomsbury Press in November 2024.

Credits: Copyright Paul Poet/Filmgalerie 451