„How-To Paint Project“ Michael Sanchez on Ull Hohn at Algus Greenspon, New York

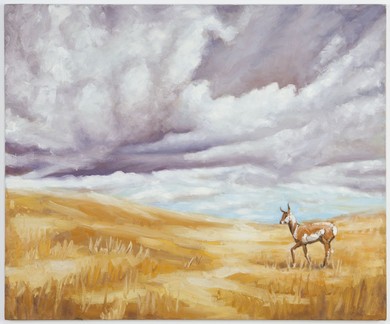

Ull Hohn, „In late October a prognhorn pauses briefly on a prairie, just before the wind becomes mixed with rain and snow", 1993

Algus Greenspon has chosen a tactful selection of works by the German artist Ull Hohn, produced from 1988 until the year of his death, from AIDS, in 1995. It is the first time Hohn’s work has been shown in New York since his 1993 exhibition at American Fine Arts. The exhibition proceeds with a minimum of direction for how to deal with Hohn’s brief period of activity, maintaining these early works, thanks to a brilliant and subtle hang, in a pressured suspense which suits them well.

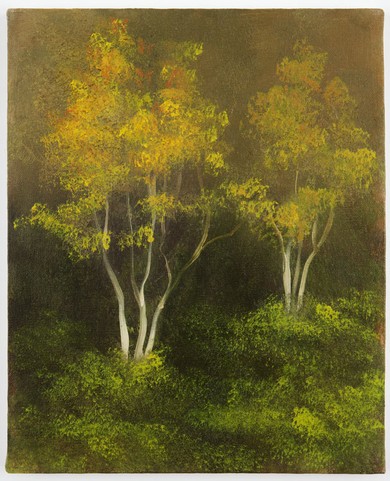

Pressure, in fact, is one possible way to begin thinking through Hohn’s work. Hohn was a student of Gerhard Richter in Düsseldorf before moving to New York in 1985, and the pressure of the teacher hovers over nearly the entire show. The ways in which Hohn positions himself in relation to Richter are perverse and unsettling. Take, for example, the untitled paintings of mountain landscapes, all produced in 1993. Formal tropes from Richter’s abstract series of the 1980s and 1990s are relentlessly downgraded through the formulae of a very different teacher, the TV painting instructor, Bob Ross. The smear in a Richter Abstraktes Bild turns into a little path leading up to a rustic bridge. Or the blurs from the „October 18, 1977" series, which Richter painted in 1988, are repurposed to render reflections of trees in pristine alpine lakes. While they can pass themselves off as overdetermined „blanks”, Hohn’s landscapes are surprisingly refined even in their badness, allowing for a density of reference not only to the landscapes of Albert Bierstadt and perhaps Caspar David Friedrich, but, piggybacking on Richter, to the Surrealist technique of decalcomania and the drags of Gustave Courbet’s palette knife (particularly in the woodsy scenes he churned out late in life).

And while the effect could be quite cute, it manages to avoid this. Hohn doesn’t allow himself an easy flippancy toward either Richter or Ross: an attitude of snobish indifference is, in fact, most often explicitly circumscribed within a given composition (for instance, the banks of a river sponged with a few brutally lame blobs of orange), leaving the rest to wallow in a scrupulous sincerity. Hohn displays no interest in either overcoming the influence of the teacher or trafficking in the prestige of his formation. Rather, he exacerbates the overbearing pedagogical influence by rerouting it onto a substitute (an amateurization of Richter which brings him down to a level below even what is encompassed by the term „deskilling”). In this sense, Hohn performs something closer to what Harold Bloom, in „The Anxiety of Influence", has called a kenosis, a repetitive ebbing or emptying of the Master. _1

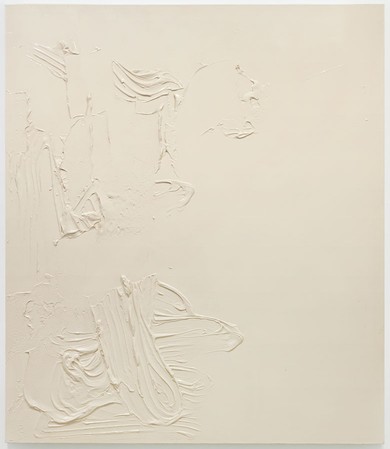

Ull Hohn, „Tan Enamel", 1993

Another low blow is delivered in the three „Tan Enamel canvases", also from 1993. To create these works, Hohn smeared modeling paste in sloppy arabesques across the surface of the canvas, but then, as if to apologize for the persistence of such a flagrantly expressive gesture, went back over the marks, partially cleaning them up with sweeping redistributions of the paste all too evocative of how icing gets spread across a cake. In one „Tan Enamel“, patches of moldy green are even visible beneath the beige enamel paint, an especially pointed example of Hohn’s insistence on the off. Comparisons are unavoidable to what, in the early 1990s, was promoted as the „abject”.

Hohn’s paintings don’t seem to enjoy their own informe muckiness too much, nor are they ever truly nasty. The surfaces of the paintings are tense, awkward in their abortive attempts to cover up their own tracks - the pressure of the half-muted. Although the most obvious similarity is with the series of five small plaster panels, also icing-like but painted a brown reminiscent of John Miller’s fecal reliefs, such tension is also visible in the landscapes, especially in the way the heavy skies push against the wispy evergreens, almost to the point of choking them.

Ull Hohn, Untitled, 1992/3

Shortly after he arrived in New York, Hohn attended the Whitney Independent Study Program, and the influence of identity politics is most evident in the group of untitled paintings - also beige, from 1991 - to which he affixed labels printed with adjectives associated with gay men: unrestrained, liquid, loose, debauched, cowardly, refined, weak-willed, delicate, gentle, licentious. While these works might be read in a rather textbook manner as counter-ideological demonstrations of the arbitrariness by which such terms, often contradictory, are associated with homosexuality, there is something about their beige matter which brings us back down. The transition from material to adjective is extremely tenuous.

A better behaved piece of identity art would be more transparently communicative. Hohn constructs a beige impasse in our attempt to transition from these signifiers to any signified. And this includes the notion of homosexuality as well: to use this concept as a way of decoding or controlling the work is to give into a logic which the works spill out from under. Flirting with its ability to be a receptacle for projections, this aspect of Hohn’s work should be considered in terms of debates on identity art in the early 1990s, particularly since it subtly avoids many of the traps which October critics identified with identity art around the Whitney Biennial of 1993 - not least of which being a "rush to the signified"._2

Ull Hohn, Untitled, 1993

But these are largely historical issues. And while this show amply proves that Hohn is deserving of historical attention, perhaps what is most interesting for the present is whether he is likely to be successfully put to work as an ”artists’ artist”. Through the previous activity of gallerist Mitchell Algus, Algus Greenspon is known for showing the work of artists’ artists, and the present exhibition has its speculative aspect. As Stefanie Kleefeld has argued, artists’ artists function as productive “lines of credit” to later generations._3 The irony is that, frequently, it is the claims made for them as “free spirits” which allow such filial lines of credit to be extended - Paul Thek and Lee Lozano, two of the most emblematic artists’ artists, are, after all, deeply anti-Oedipal figures.

Hohn has almost the opposite sensibility. Working within the Oedipal dynamics involved with „credit”, his work registers all the pressures of inhibition. That said, artists now (particularly young artists like Hohn who died at the age of just 35) are likely to find something interesting in this aspect of Hohn: perhaps the quietly twisted way he deals with the old problems of debt, inheritance and return, irreducible to either redemption or travesty, will strike a nerve.

“The Pressure of Inhibition: Ull Hohn” at Algus Greenspon, New York, November 13, 2010– January 8, 2011.

Notes:

1_ Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 87. The Politics of the Signifier, roundtable organized by Hal Foster on the 1993 Biennial, in October, 66 (Fall 1993).

2_ The phrase „rush to the signified" is from Rosalind Krauss.

3_ Stefanie Kleefeld, „On Credit: Notes on the vogue for the artists’ artist," in Texte zur Kunst,71 (September 2008).