THE OTHER DIMENSION Ian Wooldridge on Isabel Waidner's “Sterling Karat Gold”

Sterling Karat Gold tells the story of Sterling Beckenbauer. Chased by bullfighters, placed in a detention center and put on trial, Sterling, with the aid of their bestie, Chachki Smok, hacks Earth’s space-time dominion in pursuit of freedom. With the underlying suspenseful reality of queer bodies hounded by systematic state violence, Sterling Karat Gold terraforms a contemporary version of Franz Kafka’s The Trial (1925) through the compressed hermetic lens of the queer working class. Waidner’s formal innovations, influenced by the New Narrative movement, create space, lineage, and empowerment for the disenfranchised. [1]

We begin with Sterling Beckenbauer outside their flat on Delancey Street in London, wearing a bullfighter-footballer fusion look designed by Ibrahim Kamara. Bullfighters chase Sterling. Waidner maps a psychic territory with minute-by-minute football-style commentary meshed with associative thoughts. Dribbling familial recollection with the real-time bull game, Sterling thinks of their father, the famed football player Franz Beckenbauer. [2] The football-bullfight gameplay forms a triptych of escapism, trauma, and imminent violence. Then frivolousness takes agency with the focus shifting to body adornment. I think of Shamiran Istifan’s text “ALL YOU GET BACK IS THAT FLUORIDE STARE,” whereby fashion warrants inner gnosis: “I never mention the She in the system but honestly I know it myself and I am bored. ‘MOOO, I ain’t a moose bitch, get out my hay bitch get out my hay,’ while walking straight to the slaughter house, but at least in those Tabi boots.” [3]

Waidner actively collaborates and platforms their contemporaries and within the fictional narrative of Sterling Karat Gold skews authorship by featuring real-life writers Caspar Heinemann and Sophia Al-Maria. Protagonist Sterling, a fictional character in first person, details a feeling of strength through connecting with Heinemann and Al-Maria. The fictional character’s relationships to actual fiction writers awakes an epistemology of book form that disables the notion of the “auteur” by use of magical realism. [4]

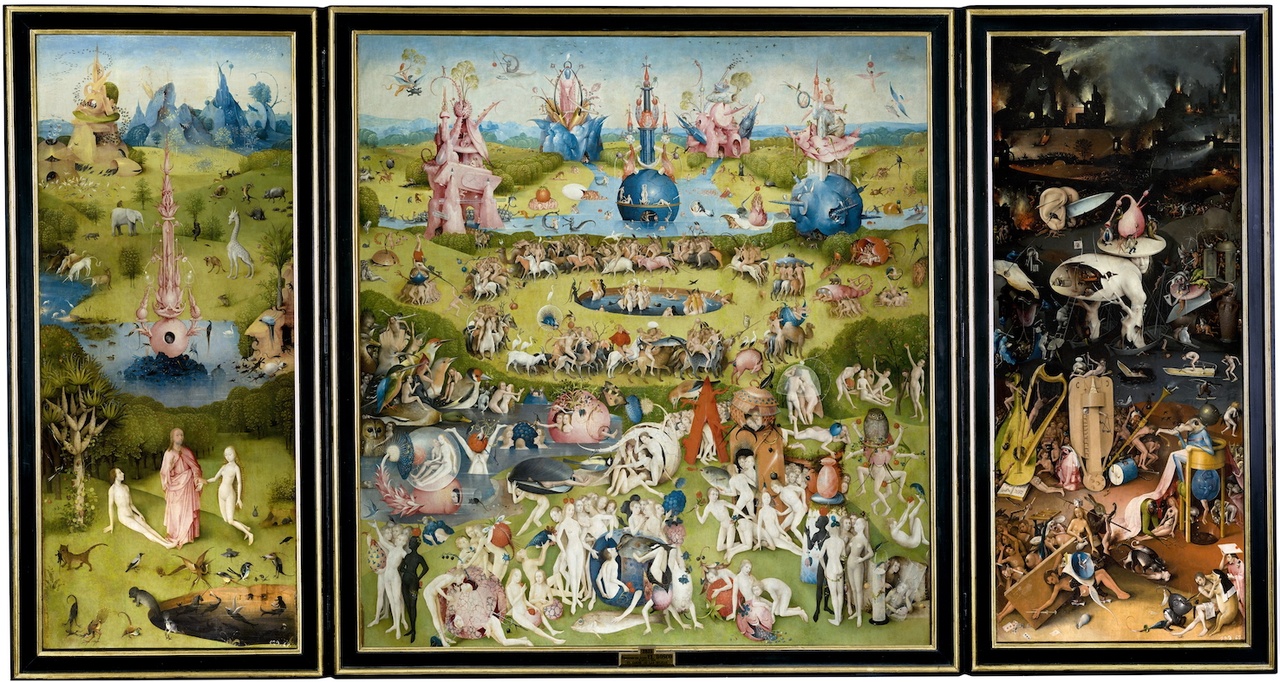

Hieronymus Bosch, “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” 1490–1510

Reality continues to position itself within the novel through the pictorial past. Sterling reflects on the cycle of a single motif – the motif being the end of a chase. The cycle begins with the cover art of the album Surf’s Up (1971) by the Beach Boys, featuring an anonymous painting of the sculpture End of the Trail (1893) by James Earle Fraser; both depict a Native American man slumped and fatigued on horseback, one a 2D reproduction and the other a 3D public monument. The final evolution of the motif is Robert Colescott’s painting End of the Trail (1976), the figure now Black, wearing Converse, tight briefs, and a tighter grin. The motif shifts from the emo musings of the Beach Boys’ appropriated depiction of suffering and exhaustion to reclamation via trickster cachet by Colescott. “THEY ARE SMIRKING DEVILISHLY. As if to say, ‘BOO’! ‘GOT YOU,’ and ‘Thought I was done for? Uh-uh, I got tricks!’” (p. 19). The mouth of Colescott’s figure flips to Smiley Smile (1967), another damp, somewhat sinister Beach Boys album. In turn, the cover art of Smiley Smile reveals itself as a softcore rendering of Hieronymus Bosch’s oil painting The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510). Bosch’s painting chimes with the start of the genocide of indigenous Americans in 1492, a genocide which Fraser later depicted in End of the Trail (1893), and which circles back to the Beach Boys album, Surf’s Up from 1971. The varying reproductions of motifs circulate with increased weight as Waidner shifts perspective with logical semantics displacing first-glance reception with lineage: a cyclical clearing of who gets to depict what and how.

Sterling is arrested and taken to Margate, the home of dreamland, a grotesque entropic landscape scanned by spaceships that travel through time via Google Earth Street View. Keyhole technology creates a systematic glitch. Waidner is a gamer. I notice a link to Daniella Brathwaite-Shirley’s online computer game Resurrection Lands (2020), about the effects of trans tourism. “AFTER WE HAD DISCOVERED THE TECHNOLOGY – TO SCAN THE EARTH – AND BRING BACK YOUR MEMORIES – BURIED WITHIN ITS HISTORY – WE DECIDED TO BRING YOU BACK – WE DIDN’T KNOW WHAT TO DO WITH YOU AT FIRST – WE THOUGHT – HOW WAS IT POSSIBLE TO STORE YOU – IN A WORLD THAT HAD ONCE ERASED YOU – SO WE BUILT THIS PLACE – THE RESURRECTION LANDS…” Both Brathwaite-Shirley and Waidner construct an anarchistic archiving through the action of scanning earth to evoke the past, resetting a system not made for the “other.” [5]

James Earle Fraser, “The End of the Trail” (replica), 1918

Sterling’s trial takes place at home, the bedroom a courtroom: “The authorities took control of the set design as there’s a protocol to be observed, apparently” (p. 87). Trails flow on a digital plane; trials, on the other hand, are held in suspension. The authority, the audience. A network, the ally. “At the head of the courtroom, the judge’s highchair. Half-throne half-toilet, it’s set up above a perfectly circular hole in my floor [...] A person under the highchair – a court reporter?” (p. 87). The judge’s highchair, with the hole in the floor, is a detail taken from the right panel of Bosch’s aforementioned triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510). The hole in the floor, a portal to another dimension, draws me toward the work of Julia Becker and her unfinished project Whole (1999–). Becker had a deal with her landlord, California Federal Bank: no rent in exchange for sorting out the previous occupant’s stuff. The tenant before her had died of AIDS with no inheritors. Becker created a cosmology whereby the building she lived in became both studio and stage. For Federal Building with Music (2002), Becker cut a hole through the ground floor into the basement and lowered a maquette of the bank, her landlord, into the basement with the stored belongings of the deceased previous occupant. Scaled models, pully systems, and ties built an energy flow of surveillance and embodiment, from living to storage. In both Waidner’s and Becker’s work, working-class domestic coding warps otherwise given infrastructure: real estate in unreal states.

The magical within Sterling Karat Gold occurs like glitches to a system grounded by the reality of segueing life from the position of being game. Encryption and transient spatial conditions merge fiction with iconography and actuality. [6] A sensibility of narrative is shaped whereby the everyday, for the “other,” is a hyperobject and queers hyper-navigate, like fight or flight in an infinite loop. [7] “Being startled out of complacency by a spaceship is one thing. Breathing spaceships like air, quite another” (p. 104). Heat, pressure, and asteroid bombardment bring to the surface precious mass; in this case: Sterling Karat Gold, a strategy game of queer realities set to Waidner’s acute perception of the now.

Isabel Waidner, Sterling Karat Gold, London: Peninsula Press, 2021.

Ian Wooldridge is an artist and writer.

Image credit: 2 public domain; 3 Sean Pathasema/Birmingham Museum of Art

Notes

| [1] | “New Narrative is a movement and theory of experimental writing launched in San Francisco in the late 1970s by Robert Glück and Bruce Boone. New Narrative strove to represent subjective experience honestly without pretense that a text can be absolutely objective nor its meaning absolutely fluid. Authenticity is paramount in New Narrative, and is possible with a variety of devices, including fragmentation, meta-text, identity politics, explicit descriptions of sex and undisguised identification with the author’s physicality, intentionality, interior emotional life and external life circumstances” (Wikipedia, s.v. “New Narrative,” last modified August 2, 2021, 18:16, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Narrative). |

| [2] | Franz Beckenbauer is a German former professional footballer and manager who once commented in regard to a professional football player coming out: “reactions in the stadium could not be predicted. Football fans are not opera fans, they aren’t so sensitive” (Thomas Winkler, “Homophobia Is Not Confined to the Terraces,” Goethe-Institut e.V., February 2014, https://www.goethe.de/en/kul/mol/20382435.html). |

| [3] | Istifan’s text is available at the Swiss Institute website for the 2020–2021 Emmy Hennings/Sitara Abuzar Ghaznawi exhibition: https://www.swissinstitute.net/exhibition/emmy-hennings-sitara-abuzar-ghaznawi/. |

| [4] | Magical realism’s trope is inclusivity, often used by the working class as a mechanism of escape. |

| [5] | See the Resurrection Lands website at: http://resurrectionland.com. |

| [6] | “Encryption, as a process, indicates the encoding of a message, rendering it unreadable or inaccessible to those unauthorized to decipher it.” Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (London: Verso, 2020), 84. |

| [7] | “Hyperobjects force us to acknowledge the immanence of thinking to the physical.” Straining normal ways of reasoning. Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 10. |