THE CONVENTION OF THE PRESENT, THE ART OF THE PAST Joseph Henry on virgil b/g taylor at Artists Space, New York

“virgil b/g taylor: Minor Publics,” Artists Space, New York, 2022, installation view

Most recent photographs of Sol LeWitt’s Black Form: Dedicated to the Missing Jews (1989) show the sculpture in contradistinction to its municipal backdrop, the Altona city hall in Hamburg. In one image from the official “Memorials in Hamburg” website, Black Form’s dark mass of bricks sits obdurately in front of the building’s pedimental façade. It complicates access, blunts the architecture’s authority, intrudes on the fantasy of a smooth flow of German history. A recent photograph taken by the artist virgil b/g taylor, however, captures LeWitt’s sculpture from the obverse angle. The camera has to look past two climbing branches in the foreground to catch LeWitt’s sculpture, almost surreptitiously. The charcoal-colored monument dwells in the background behind rows of foliage, no longer sentinel in civic space but now furtive somewhere off in the distance.

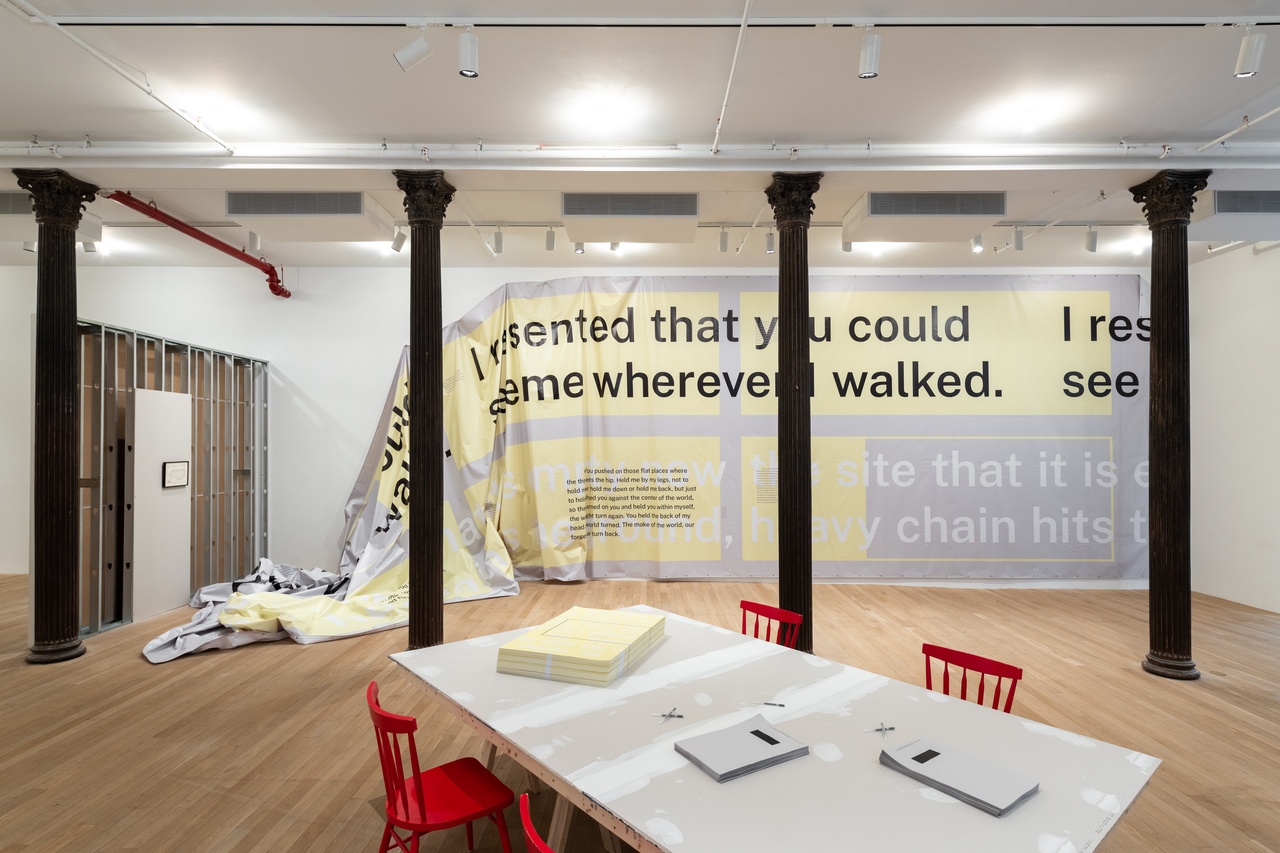

This inverted perspective on Black Form expands into an ethos and an epistemology in taylor’s “Minor Publics” installation at Artists Space. Motivated by but not strictly about LeWitt, the project looks to the story of Black Form as an occasion to think through both abstract form and abstracted modes of sociality. Documentation of LeWitt’s work, from a preparatory sketch to taylor’s photograph, only sparsely populate the gallery. A cluster of related catalogues and scholarly books line two windowsills, while geometrically styled posters dot the walls at uneven intervals. What dominates “Minor Publics” are two skeletal barriers, one a half-exposed piece of drywall and the other a metal scaffolding. A large swath of vinyl mounted to the wall crumples onto the former, and a length of fabric droops down off the latter. Text and language become the primary instruments across these materials, whether the declamatory statements impressed on the vinyl, the bibliographic research compiled in the gallery, or a poetic “script” both available as a printed copy in the gallery and uploaded online.

It’s in this broadsheet that taylor proposes the central apparatus or concept of his exhibition, based on the synagogal platform from which the Torah and haftarah are read during Jewish religious service. “Bima, or בימה, or βήμα,” its first line goes, “or other words asking you to bring yourself forward and name the lines that hold you in place.” A bima was also the tribunal from which orators in ancient Athens addressed their audiences, and taylor seems, with LeWitt, invested in a new configuration of a bima that can gather the “minor publics” of his title. Yet this configuration is only ever a desire at Artists Space, where taylor’s texts and installation never really induce a sense of clear, self-possessed articulation. Speech acts falter and conversations mire in their own voices, leading to a certain ambivalence regarding cultures of memory and monumentalization.

Sol LeWitt, “Black Form: Dedicated to the Missing Jews”, 1989

These cultures still propel politics and aesthetics in Germany today, where LeWitt first set up his edifice in 1987 in Münster, and where taylor, a “US faggot living in Germany,” as he puts it, now works. Black Form belongs to the distinct tradition of the counter-monument (Gegendenkmal), which beginning in the 1980s proposed sculptural interventions that refused both a rehashing of imperialist 19th-century styles and a concomitant melancholia that mourned war atrocities without insisting on political accountability. [1] For a commission from Skulptur Projekte Münster, LeWitt stationed the work directly in front of an 18th-century Schloß that, since the 1950s, had been repurposed by the city’s Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität. [2] Black Form was to be “a piece that was completely different from the lacy architecture behind it,” as LeWitt recalled. “I made it in a sort of ungainly block. I wanted it to be hard to swallow in terms of form and completely antithetical to its site.” [3] And antithetical it was: after LeWitt officially donated Black Form to the city of Münster, university administrators repined over its inconvenient location and city inhabitants bemoaned its hard smack into the Baroque surround. Despite pleas from LeWitt and the Skulptur Projekte curators, the university jackhammered Black Form to pieces in March 1988. In the months prior, the Altona district council and Hamburg Kunstkommission had already discussed duplicating Black Form for their own monument to the region’s Jewish history. When the bricks tumbled in Münster, Altona presented an opportunity to resurrect LeWitt’s sculpture in even larger dimensions. [4] This was in November 1989, as a second bit of masonry fell in Berlin.

Part of taylor’s inquiry is to revive the politically committed, even religious quality of LeWitt’s oeuvre, which typically persists as classic art historical conceptual art or quasi-apocalyptic wallpaper, as seen in the eager all-in presentation of LeWitt’s wall drawings by most contemporary art museums. [5] So too does taylor want to cast the German counter-monument within current disputes of historical commemoration, whether those involving the United States’ white supremacist legacy or Germany’s extremely belated colonial reckoning. [6] Yet as central as the history and function of Black Form is to taylor’s project, these specificities don’t materialize so readily in gallery space. Moments in Black Form’s biography – its designing, demolition, and relocation – appear only in scant documentation. The narratives of LeWitt’s project get outsourced to the catalogues and art historical texts taylor lays out (much of this review’s research thus occurred “on-site”).

Yet even these materials play a supporting role to taylor’s primary text, the script for “Minor Publics.” Riffing on LeWitt’s own strategy of serial variation, taylor stylizes the monument into alternating bands of black and white that demarcate each expansive page into upper quotations typically explaining Black Form or the bima and lower passages written in intimate second-person narration. The latter soliloquizes to an unidentified addressee through the talk of both performance-studies theory (“There is a stage where we find ourselves present, presented, presenting”) and dark-room phenomenology (“Another slipped in and then there were three of us, undressed and feeling that nothing as yet another body, pressing”). From the exhibition’s half-built walls to its evocation of LeWitt to its erotic prose, “Minor Publics” allegorizes these modes of encounter and deliberation into its own bima in the expanded field.

“virgil b/g taylor: Minor Publics,” Artists Space, New York, 2022, installation view

One qualm could be uttered: that this is all abstraction as over-generalization rather than potentialized form. Taylor evokes art historical abstraction only in the glyphs of his script, instead opting for a scenography of wordy banners and provisional printed matter. Something is really lost in the flattening of LeWitt’s monument into a mere organizing concept or, even worse, a good-design trademark. (A friend pointed out the ready use of sans serifs akin to the fonts Favorit and Karla – the frequently chosen typography of digital app interfaces.) [7] The sculpture’s force resides partly in its additive manufacture and pained agglomeration of bricks; this piecemeal laboring distinguishes Black Form from the direct slice of a cognate work like Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc (evoked by taylor in the gallery library, no less). The project’s overall enervated tone, especially compared to the probing cheekiness of taylor’s online project fag tips, raises a question: What kind of participation or collectivity thrives around this new bima? Although taylor shrewdly avoids a literalized understanding of expression as social participation (think of all the art inviting passersby to speak into an unassuming microphone), acts of reading and study bind each subject to the next in “Minor Publics.” But not study in the vitalized sense Harney and Moten celebrated in The Undercommons, “talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three.” [8] At Artists Space it’s study as institutionally sanctioned research, as quiet consultation and all those exhibition catalogues arrayed for perusal. Even the speaker of the exhibition’s script feels privatized, hermetic, tethered to the self’s perspective as they try to limn new kinds of worldmaking.

What comes across in “Minor Publics” is the collapse of a viable bima as much as its instantiation. One detail is telling: the yellow and gray vinyl that streaks across a gallery wall ultimately crumples on the left side and, with it, the lines printed thereupon. In “I resented that you could see me wherever I walked,” “see me” buckles to the floor in an alienated, almost defeated interaction. For taylor, publicity occasions misrecognition and overexposure as much as acknowledgement. Histories get buried, speakers try to make themselves heard, and even the clearest of forms obscure. LeWitt’s own monument, given its reputation as an icon of counter-memory and historical admission, is constantly defaced by voices seemingly sympathetic to its politics. As much as fascists carve swastikas into the brick, so too do other actors graffiti complaints against municipal austerity and disinvestment. And then each year, citizens paint the bricks in a new coat of black. [9]

“virgil b/g taylor: Minor Publics,” Artists Space, New York, February 4–April 23, 2022.

Joseph Henry is a PhD candidate in the art history program at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY), where he’s writing a dissertation on German Expressionism.

Image Credits: 1. + 3. Courtesy of Artists Space, photos: Filip Wolak; 2. CC BY-SA 2.5 , photo: Gunnar Ries

Notes

| [1] | For an early overview of these projects, see James E. Young, “The Counter-Monument: Memory against Itself in Germany Today,” Critical Inquiry 18, no. 2 (Winter 1992): 267–96. |

| [2] | On the history of Black Form, see ibid., 267–67; David S. Areford, “Voices beyond the Wall: On Sol LeWitt’s Jewish Art,” in Locating Sol LeWitt, ed. David S. Areford (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021), 231–65; and Angeli C. F. Sachs, “Neue Formen der Erinnerung. Zwei Mahnmale von Jenny Holzer und Sol LeWitt in Deutschland,” Kunsttexte.de, no. 3 (2002): 4–6. |

| [3] | Sol LeWitt quoted in Martin Friedman, “Construction Sights,” in Sol LeWitt: A Retrospective, exh. cat., ed. Gary Garrels (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2000), 57. |

| [4] | For the Münster exhibition, LeWitt also created a work titled White Pyramid on the other side of the palace. LeWitt stages the affects of black against white, modernist sculptural form against a venerable Egyptianizing tradition. |

| [5] | On the religious dimension in LeWitt’s art, consider even the very opening words of his 1969 “Sentences on Conceptual Art”: “Conceptual Artists are mystics rather than rationalists.” In 0–9, no. 5 (January 1969): 3, reprinted in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 106. |

| [6] | In reviving the concept of the bima, taylor may also be after a new politicization of a Jewish heritage in the midst of Palestine’s occupation. |

| [7] | Thanks to Asha Sheshadri for this observation. |

| [8] | Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Brooklyn: Minor Compositions, 2013), 110. |

| [9] | Areford, “Voices beyond the Wall,” 238. |