DIS/CONTINUITIES Krista Bailie on Christine Schlegel at Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst (BLMK), Cottbus

“Christine Schlegel: Lärmende Stille,” BLMK, Cottbus, 2024

When she first accessed her Stasi files in 1997, Christine Schlegel was surprised by the mundane details the surveillance reports contained. As it turned out, she had underestimated the degree of scrutiny she and her daughter had endured as socialist subjects. [1] While aware that she was being monitored, Schlegel had assumed that the state’s interest in her was due to her connection with members of Dresden’s underground art scene, but she had not expected finding her everyday activities documented in her files, too. [2] Beyond this, the monitoring and preservation of many of her artworks as evidence revealed an unexpected irony: The Stasi had inadvertently been creating an archive of her collages and overpaintings that could not be exhibited publicly in the GDR. In an effort to process the unexpected extent of state surveillance and to regain control over her own work and life, Schlegel combined photocopied excerpts of her files with personal photographs, handwritten comments, small drawings, thread, pieces of metal, and the reproductions of her artworks. The resulting series, Eingeschweißte Überwachung (Shrink-wrapped surveillance), produced in 1999, is on display as part of the artist’s solo exhibition “Lärmende Stille” (Noisy silence) curated by Ulrike Kremeier, the director of Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst (BLMK) in Cottbus. [3]

One of the collages from this series, Stasiakten 000024 + 000026 (1999), is a particularly compelling example of Schlegel’s approach of weaving together personal experience, cultural critique, and historical specificities to create broader narratives about the ongoing violence inherent in systems of power and control. In the center is a surrealist photomontage Schlegel created in 1980, featuring a composite figure lounging in an ambiguous interior/exterior space serving as a focal point for the larger collage. Outside of this repurposed artwork, the artist has included Stasi file excerpts in which those informing on her claim that she is “frequently observed to be idle during the day,” and unable to fulfill her obligations, specifying that since her divorce, her home had assumed a “run-down” condition. These excerpts, juxtaposed with photographs of Schlegel surrounded by her artwork and combined with handwritten phrases such as “Hände in den Schoß legen,” an idiomatic equivalent to the English phrase “to twiddle one’s thumbs,” exposes the inconsistencies between her lived experience and the Stasi recordings. Despite the humor present in the collage, Durs Grünbein’s quote “…Worte, mit denen du leben mußt, sind nicht komisch” (Words you must live with are not funny), which appears on nearly every collage panel of Eingeschweißte Überwachung, provides a reminder of the enduring psychological impact of the systems of control in the GDR.

“Christine Schlegel: Lärmende Stille,” BLMK, Cottbus, 2024

Compiled from fragments of her life and her archive, Schlegel’s works seal together her key themes – personal trauma, collective memory, and artistic agency – to represent complex issues and transcend particular historical moments. The artist’s conceptual strategy of recontextualization is marked by repetition, temporal folds – the convergence of multiple points in time within a single composition – and what philosopher Karen Barad terms “agential cuts,” [4] as well as iterative reworkings that interweave disparate elements coalesced during her time at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. The curator Christoph Tannert, who was not involved in this show but has written extensively about Schlegel since they first met as students, notes that this approach emerged from her early rejection of the prescriptive aesthetics of socialist realism taught at the school: To counter it, Schlegel developed a methodology inspired by Dadaist collage techniques, juxtaposing disparate, often fragmented images and materials to create new constellations of meaning. [5] With almost 150 works on show, this exhibition reveals her application of these principles to her paintings, films, ceramics, artist books, and other intermedial explorations.

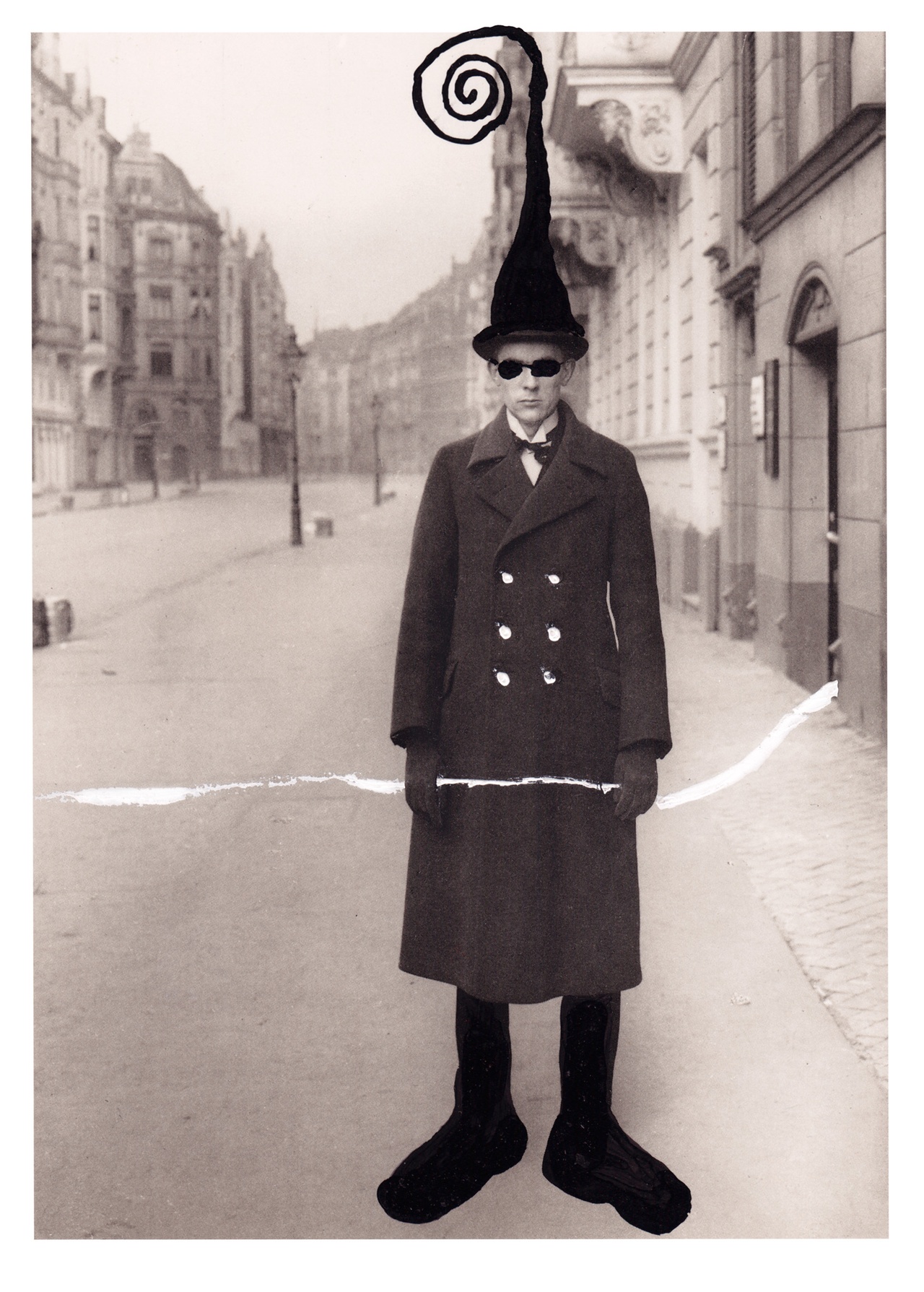

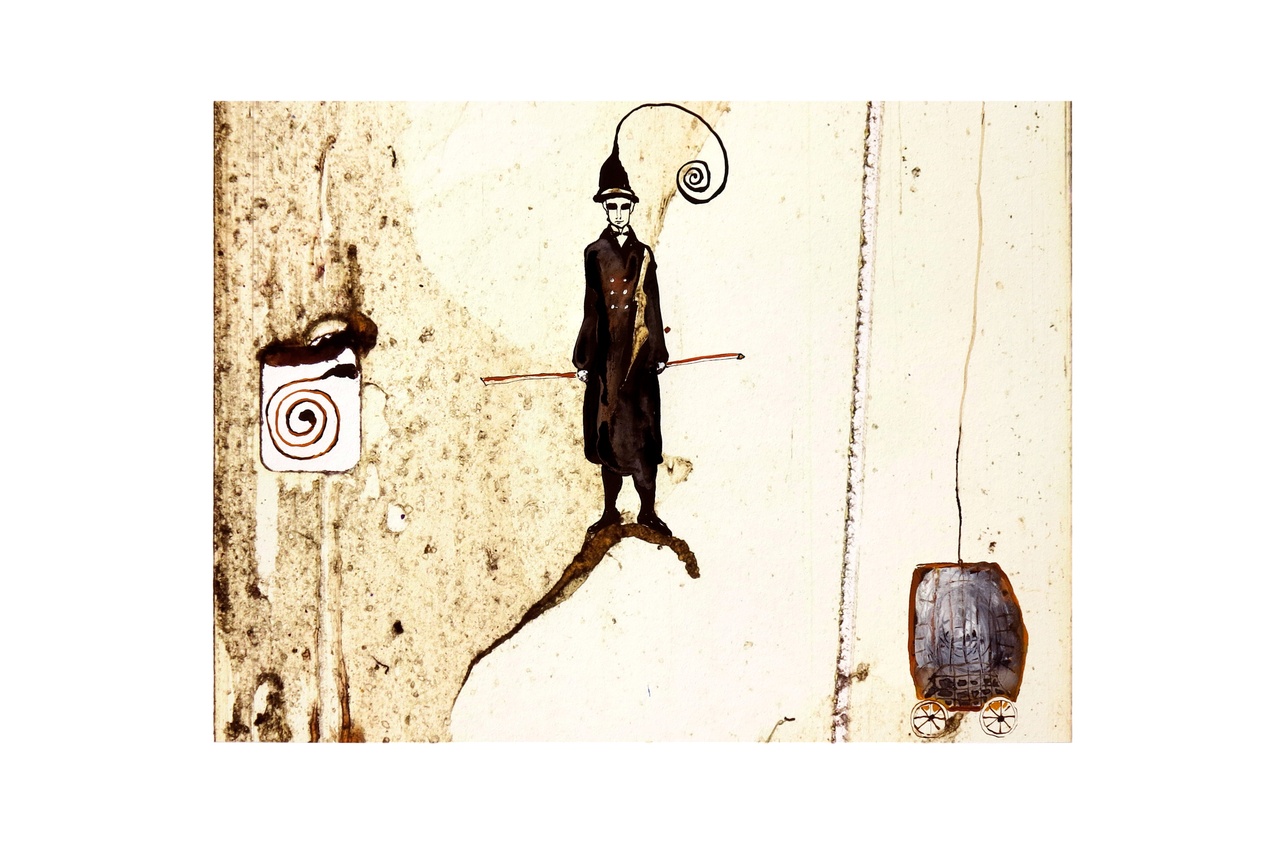

Reminiscent of the Dadaists, Schlegel frequently uses recognizable figures to entangle cultural and personal memory, embedding them within critical reflections that require specific background knowledge to untangle. A striking example of this is Postkartenübermalung (1988), her reinterpretation of August Sander’s 1927 portrait of Neue Sachlichkeit painter Anton Räderscheidt: Here, Schlegel appropriates a postcard featuring the classic portrait and transforms it into a surrealist composition by adding comically large boots, dark sunglasses, white jacket buttons, and an elongated hat topped with a spiral motif. In the original photo by Sander, Räderscheidt holds a cigarette, which Schlegel overpainted and extended to form a strip of white paint, which trails into the open doorway of a nearby building, mooring the posing painter to the environment. With this intervention, she appears to critique the New Objectivist commitment to unflinching realism, proposing that absurdity can reveal additional layers of truth beyond objective representation. As with Eingeschweißte Überwachung, Postkartenübermalung is part of a long-term investigation and closely linked to other works in Schlegel’s oeuvre. In 2023, she revisited her aforementioned rendition of the Räderscheidt portrait. In Strukturen 1, it reappears as a drawing, precariously balanced in the foreground on a thin branch of ink; the abstract scene behind the figure is marked by decay and composed through scratching and layering. The base material, a mixed media collage combining painterly with film montage techniques, seems to be the essential element in this work: Inspired by her past in the GDR, when she was forced to make use of what was available, following a method she describes as “cooking a good soup of out nothing,” Schlegel drew and painted over a still from her 1983 experimental film Strukturen in which she applied overlays, color, and scratch marks onto Super 8 film. [6] Her repurposing of materials appears to be a way of paying tribute to the deep time manifested in objects and of foregrounding their agentic potential. In the context of Schlegel’s artistic practice, it also relates to the conscious and subconscious creative cycles she performs, to her persistent returning to particular themes, to the revisitations of ideas and images.

While Schlegel’s approach of layering, fragmentation, and recontextualization is a rich conceptual strategy, it can sometimes obscure the historical specificities that contribute to the depth of her work. For example, the use of the film still from Strukturen as the base of Strukturen 1 refers to the artist’s collaboration with dancer Fine Kwiatkowski during the first Intermedia Festival that took place in Coswig (close to Dresden) in 1985. The festival, an event its co-organizer Christoph Tannert describes as a “survivor’s meeting” for those who had not yet left the GDR, [7] was a significant moment for East Germany’s nonconformist scene, bringing together artists, filmmakers, dancers, and musicians in a fleeting space of creative freedom. In the pair’s performance titled Strukturen und Wandlungen (1984–91), Kwiatkowski dances in front a projection of Schlegel’s film; her body appears to be dissolving into and resurfacing from the scratched and painted-over footage, creating a dynamic interplay of abstraction and embodiment. With this context in mind, the still in Strukturen 1, printed on high-quality Hahnemühle paper, carries significant historical weight. Without knowledge of its origins or its connection to the festival, the work is bereft of an important layer of meaning. The obscurity and rich referentiality of Schlegel’s work can be frustrating at times. But it also mirrors the complexity of historical memory, forcing us to ask what is excluded, concealed, or overwritten – and why?

Christine Schlegel, “Postkartenübermalung,” 1988

Zdenka Badovinac, curator of the Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana, observes that Eastern Europe’s historical “lack of a functioning art system” has frequently resulted in the uncritical adoption of Western frameworks for meaning-making within exhibition practices. While projects like Badovinac’s “Arteast 2000+ Collection” (2000) or “The Body and the East” (1998) sought to provide new curatorial approaches through the exploration of “micro-political situations” to recontextualize the Eastern European art system, such efforts remain largely confined to regional contexts. [8] Even ambitious exhibitions that explicitly aim to disrupt the art historical narratives of Eastern Europe through transhistorical juxtapositions, such as Centre Pompidou’s “The Promises of the Past” (2010), frequently end up reinforcing the “East/West” binary. Despite their progressive intentions, such curatorial projects often fall back on thematic groupings and simplified narratives of “experimental art” and “state resistance,” which are most frequently formed and told from a Western perspective. [9]

“Lärmende Stille” situates Schlegel’s practice within a broader art historical context by connecting it to a long avant-garde tradition of collage, where bridging reality with fictional worlds serves as a powerful form of sociopolitical critique. Contextualizing Schlegel’s ambition to create “pictorial counter-narratives” and disrupt conventional representations of reality with related Surrealist, Dadaist, and Cubist techniques, [10] Kremeier's curatorial approach contrasts previous presentations that simply framed Schlegel as one of several “radical” GDR artists. [11] Moving beyond such generalizations, “Lärmende Stille” reveals how Schlegel’s evacuation of her personal archive transcends temporal and ideological boundaries.

The exhibition offers moments of thoughtful curation, makes good use of transitional spaces, and establishes considered connections between works through proximity. However, as I navigated some of the more densely packed rooms in the gallery, I found myself troubled by the lack of space for contemplation. Schlegel’s practice is a kind of transhistorical hide and seek, which turns viewing her work into a durational exercise supplemented with numerous layers of information – a repeating image element, a historical reference or anecdote, a repurposed title – that often only become apparent on closer inspection and with the help of background information. The exhibition asks viewers to bring a good deal of broad cultural and specific historical knowledge – or to pay close attention to the ample information provided to decode deeper meanings and connections embedded in Schlegel’s work. Well-structured wall texts help to navigate each room, noting overarching themes and specifics, such as the way certain art historical figures “wander through the artist’s oeuvre as recurring narrative elements.” [12] But the sheer volume of artworks and backstories is a bit overwhelming. While the curators certainly succeed in presenting an impressive overview of Schlegel’s diverse practice, the show’s density at times limits opportunities for deeper engagement with individual, multilayered works.

Christine Schlegel, “Strukturen 1,” 2023

At a time marked by interconnected crisis and the resurgence of authoritarian ideologies, Schlegel’s polytemporal approach feels like a crucial intervention, inviting us to consider our own experiences alongside broader historical patterns. The accessibility of themes like Stasi surveillance, a violence enacted four decades ago, feels uncannily familiar in our current climate of eroding privacy and increasing governmental control. Through art that intertwines personal experiences with collective histories, Schlegel offers a strategy for engaging with the past – not as something to be looked back on, but rather, something which has always been and still is.

“Christine Schlegel: Lärmende Stille,” BLMK, Cottbus, November 30, 2024–February 16, 2025.

Krista Bailie is an artist, art historian, and writer. She lives and works in Vancouver.

Image Credits: photos 1.– 2. Bernd Schöneberger; 3.– 4. © Christine Schlegel / Antonia Schlegel

Notes

| [1] | Christine Schlegel, Hautlos: Eingeschweißte Überwachung (Berlin: Gerhard Wolf Janus Press, 2001), 39. |

| [2] | Schlegel, Hautlos, 39. |

| [3] | Christine Schlegel, “Stretch-Wrapped Surveillance,” in Von Ferne: Bilder Zur DDR = From Far Away: Images of the GDR, exh. cat., ed. Michael Buhrs, Sabine Schmid, and Museum Villa Stuck (Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2019), 381. |

| [4] | Karen Barad’s concept of “agential cuts” refers to the process of making distinctions while maintaining certain connections – a “cutting together/apart” that holds disparate elements in dynamic tension. This process can be seen in Schlegel’s practice of selecting, altering, and layering materials while preserving elements of their original contexts. See Karen Barad, “Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/continuities, SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come,” Derrida Today 3, no. 2 (2010): 265. |

| [5] | While Tannert was not involved in the curation of this exhibition, Schlegel and Tannert’s professional relationship began during their time in the GDR. Tannert, who served as the artistic direction of Berlin’s Künstlerhaus Bethanien from 2000 until his recent retirement in 2024, has been a significant voice advocating for a more nuanced understanding and recognition of East German art. See Christoph Tannert, “Fernab der Kolossalwahnproduktion,” in Schlegel, Hautlos, 8. |

| [6] | Christine Schlegel, Kind der weißen Henne: Reservate der Kindheit (Dresden: Sandstein, 2015). |

| [7] | Barbara Büscher, “Intermedia DDR 1985 – Ereignis und Netzwerk,” Perfomap, https://perfomap.de/map2/geschichte/intermedia-ddr. |

| [8] | Zdenka Badovinac, “Museum of Parallel Narratives,” in Post-War Avant-Gardes Between 1957 and 1986, ed. Christian Höller (Barcelona: L'Internationale Books, 2011), 19. |

| [9] | Ana Bogdanovic, Conference Report of “Mythmaking Eastern Europe: Art in Response,” Institute of Art History, University of Zurich, Oct 18, 2012. ArtHist.net, January 30, 2013. |

| [10] | Ulrike Kremeier, curatorial essay in Mondvogel: Katalog zur Ausstellung Christine Schlegel. Lärmende Stille (30.11.24–16.2.25), ed. Annett Jahn and Ulrike Mönnig (Cottbus: Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, 2024), 90. |

| [11] | “Medea Muckt Auf: Radikale Künstlerinnen hinter dem Eisernen Vorhang” [The Medea Insurrection: Radical Women Artists Behind the Iron Curtain], curated by Susanne Altmann (Dresden: Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, December 8, 2018–March 31, 2019). |

| [12] | Ulrike Kremeier, wall text for “Lärmende Stille,” exhibition at the Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst, Cottbus, November 30, 2024–February 16, 2025. |