As Stefan Germer noted in the 1996 issue of TEXTE ZUR KUNST on exhibition politics, it was not the growing reliance on private sponsorship that transformed cultural institutions following the budget cuts of the early 1990s, but rather the shift toward evaluating economic profitability and visitor metrics as criteria for public funding. Against that historical background, the current museum landscape in the Norwegian capital offers an interesting case study: Although cultural funding remains a pillar of the welfare state – and has even increased alongside the state’s wealth – Norway’s museums have been consolidated and subjected to New Public Management practices, extending beyond administration into curatorial strategies. Live Drønen reports on how destination-building efforts and the expectation of a return on state investment – particularly in the form of a striking waterfront skyline – shapes exhibition politics in Oslo today and how mid-sized institutions and artist-run spaces counter this development.

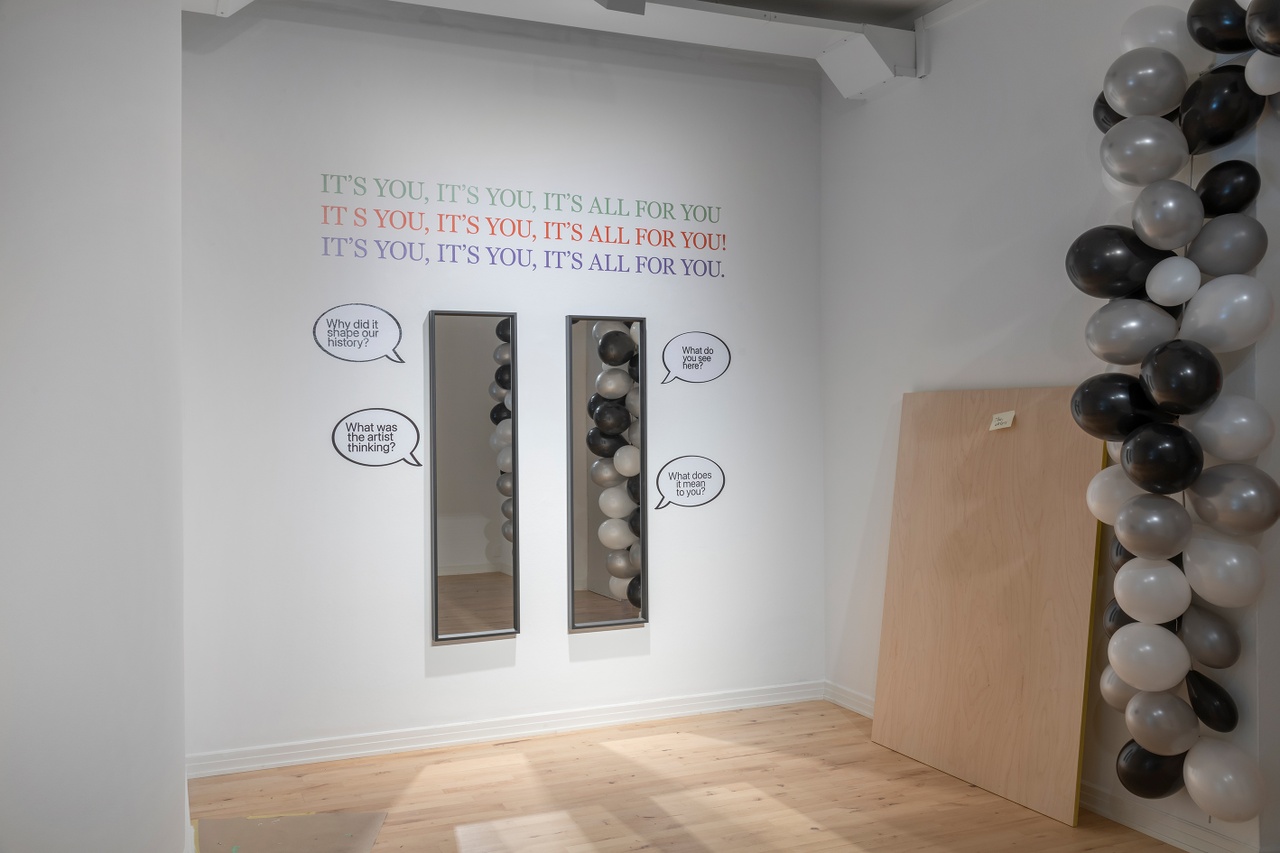

With the 2024 exhibition “Arbeidstittel: The Workers” at Haugar Kunstmuseum, a public art museum an hour’s drive from Oslo, curator Erlend Hammer broached a merciless criticism of certain neoliberal, bureaucratic, and cultural mechanisms affecting art institutions in Norway today. Having worked as both a critic and curator in Oslo over the past years, these themes were highly familiar to me, and the project encapsulated many discussions which were buzzing. The exhibition poked fun at an increasing focus on branding, visitor numbers, and mediation, staging exaggerated interventions and exhibition props amidst works of both historical and contemporary artists form Norway and abroad, ranging from Christian Krohg and Edvard Munch to Allison Katz, Merlin Carpenter, and Vibeke Tandberg. The parodic exhibition design included mirrors with speech bubbles containing blunt questions, such as “What was the artist thinking?,” intended to make visitors reflect on the show. An immersive corridor, made up of cheap blinking lights and wind fans, mimicked a sound and light installation in an Edvard Munch and Francisco Goya exhibition at the Munch Museum in Oslo – an institution which, together with the National Museum, was particularly under scrutiny in the show. In the local art scene, Hammer’s exhibition was perceived as a breath of fresh air by those agreeing with its critique and a cause for annoyance by those who advocate for visitor interaction; finally, it was criticized for being too self-referential and uncomprehensible for non-art-world audiences.

Since rebuilding the country after World War II, Norway has had a strong tradition of generous cultural funding as part of its democratic welfare state model. Schemes for government grants for artists date back to 1948, the Arts Council was established in 1965, and since the country’s discovery of oil in the 1970s, the sums spent on culture have proportionally increased with the state’s riches. Working grants for visual artists are awarded as an annual salary for one to five or ten years, there are support schemes for artist-run spaces, exhibition projects, and publications, and most public art museums get more than 70 percent of their funding from the state, county or municipality. Yet although cultural budgets have, by and large, continued growing over the past years, in the municipalities, they are declining, budgets are increasingly centralized, and visual arts are being downgraded.

In the early 2000s, the cultural ministry of Norway initiated a reform through which 300 museums of vastly different disciplines were consolidated under 60 joint administrations. The aim of the reform was to “establish strong professional environments that would strengthen museums as active and relevant arenas for knowledge and experience.” It was met with criticism from art museums for weakening their economic and administrative autonomy, blurring their distinct identities, and adding unnecessary bureaucracy. Hammer’s exhibition grew out of his frustrations from two years of working in a consolidated art museum: “Haugar Kunstmuseum had been lumped together with institutions from such wide and unrelated areas as the Viking ages, whaling, Pacific explorations, and aluminum. I wanted to highlight the absurdity of art museums being forced into consolidated structures like this.” In his experience, one of the most problematic consequences of the reform has been the creation of institutions that are expected to run like efficient private companies. In a country where cultural funding still has strong public support, the tendency of museums to adapt corporate strategies and to serve entertainment purposes seems counterintuitive, yet it is a shift connected to both global developments and local concerns.

In a recent government report on Norway’s cultural politics, culture-based tourism was stated as a priority. Likewise, internationalization has been a long-standing ideal in cultural politics and focuses on both promoting Norwegian artists abroad and inviting international agents and audiences to the country. Since around 2013, there has been a demand for museums to acquire more private funding and sponsorship – a trajectory originating in the conservative center-right’s market-liberal cultural politics, and which has gained public momentum through several polarizing debates around public support for the arts over the past years. “Arbeidstittel: The Workers” considered these complex factors that seem to have thrown many institutions into an identity crisis resulting in an emptying out of content.

Nationalist Turns

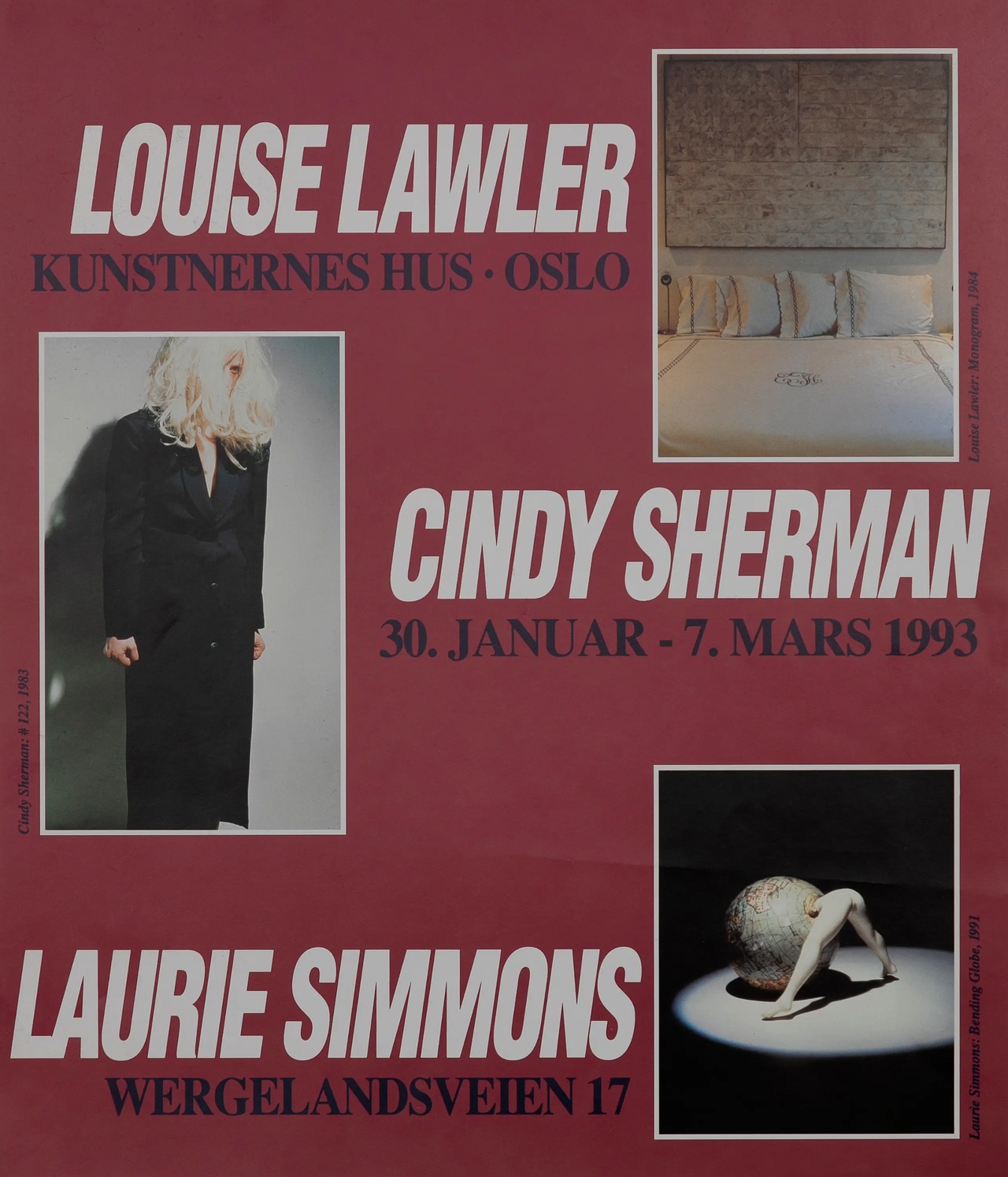

After prolonged construction periods, the aforementioned Munch Museum and National Museum opened in new, massive buildings in Oslo in 2021 and 2022 respectively. As the museums have grown bigger, funding has become sparser for the mid-sized institutions. Several of the latter have a long history as political advocates and artists’ unions that have lobbied for the field’s existing support structures. One mid-sized institution is Kunstnernes Hus (The Artists’ House), founded by artists in 1930, with a tradition of contributing to merging the local scene with international impulses. Its current artistic director, Sarah Lookofsky, tells me that presenting an international program will get more difficult in the years ahead: “The focus on the largest institutions has made it difficult to compete for funding and attention.” She also adds another shift: the introduction of fees for non-EU students across Norwegian higher education, which were implemented in 2023. “The recent nationalist turn to introduce astronomical fees at the art academies means that major parts of the world will no longer be represented in the student body.” In a country that is already at the periphery of the international art world geographically, this leads to a loss of importantly diverse perspectives and talent. The admission of new students from outside the EU/EEA is estimated to have already fallen by 80 percent since the introduction of the fees. Very recently, the Labour Party announced that it is proposing to reverse this decision. Elisabeth Byre, the director of Oslo Kunstforening – founded in 1836 as an exhibition space and members association to support contemporary artists – has similar concerns: “The basic funding for operations is not enough, and we are left working on a project grant basis, which in practice means that artists apply for production subsidies themselves. These grants are hard for international artists to get,” she says.

For Kunstnernes Hus, these conditions have led to not only showing art but also being a gathering space. “We are focusing on that mandate, hoping that human scale and social settings will help stave off the threat of a downward spiral where less money and attention leads to even smaller means to do proper exhibitions and to promote them,” Lookofsky explains. Similarly, the artist-run institution UKS (Young Artists’ Society) has reverted toward focusing more on conversational and collective formats, as well as discussions around infrastructure, and abandoned the format of solo exhibitions altogether. While precarious working conditions and a sense of powerlessness in the face of the new museums make it necessary for these institutions to rethink and reevaluate their programming, self-questioning is rooted as a spinal reflex in the institutions’ history of experimentation and opposition. As such, to foster a healthy dynamic in the field and opportunities for early-career practices, such spaces are vital to keep afloat.

“A Particularly Norwegian Trend”

Both the Munch Museum and National Museum underwent redesign processes upon opening in new buildings, resulting in new visual identities and a rebranding as MUNCH and Nam. In Hammer’s opinion, the New Public Management thinking that was brought into the sector with the museum reform has made both institutions favor quantitative goals over qualitative: “There’s a poor understanding of artistic expertise, quality, and importance. Curators have to make exhibitions that adhere to the ‘strategic visions’ of directors and boards who are mostly interested in visitor numbers and ‘destination-building,’” he says. Another person who has openly criticized institutional politics is Ina Blom, professor of art history at the University of Oslo and the University of Chicago. She has been outspoken about the tendency in Norwegian museums to privilege general leadership experience over artistic and art historical competence in directorial positions, which she has dubbed “a particularly Norwegian trend.” On the question of why she thinks this is so, Blom sketches out a complex set of factors – one being political signals from the Ministry of Culture and the City of Oslo:

The state and city’s massive investments in new museum buildings and the sizes of the organizations of consolidated museums have led to a heightened emphasis on audience numbers and various types of strategic initiatives, and there seems to be a widespread idea in Norway that such processes cannot be led by an art historian. Yet in major museums around the world art historians serve as directors of enormous institutions which face far greater economic, organizational, and cultural challenges than the Norwegian ones.

What is clearly at stake once the specific competence on art – what these museums exist to manage – is not rooted in the directorial teams is the artistic integrity of the exhibits and the institutions’ programming as a whole.

Draining Energy

How do these circumstances affect what is being shown in the museums? In the National Museum, exhibitions are made on the basis of a so-called core group model, in which a project manager, a curator, and an education curator work together to develop the overall vision for the exhibitions. Education curators are responsible for all activities connected to art mediation. The position was created at the museum in 2005, around the time when the formerly separate museums were consolidated. At MUNCH, curators lead the development of exhibitions in close collaboration with other departments, while operating according to programming strategies and audience goals. “When the curators no longer have clear leadership in the exhibition-making process, the time and space needed for more substantial art historical and curatorial conversations is also given less priority,” says Blom, and in Hammer’s opinion, these constructs have led to a “dumbing down of both programming and mediation.” The director of MUNCH, Tone Hansen, does not agree with the criticism. She highlights that the museum is still under development and has recently hired a Director of Collection, a research curator specialized in Indigenous cultures and two new curators specialized in modern and contemporary art respectively; “Curators and art historians are at the core of our program development at MUNCH. We work actively to balance curatorial depth with strategic leadership and audience engagement. But even more importantly, we work with artists or the artworks as a core,” says Hansen. The National Museum’s director, Ingrid Røynesdal, believes the museum needs people with a broad range of backgrounds: “Artistic knowledge and experience are essential for us as an institution to succeed in managing Norwegian cultural heritage while creating new and exciting experiences for a broad audience. However, running the National Museum on the scale and in the format that we do today requires a diverse range of expertise.”

Last year, Norwegian critic Nicholas Norton wrote a comment on the emptying out of content in museums. He particularly focused on an exhibition at MUNCH revolving around the young Norwegian rapper Arif. It featured a music video and recording studio, where the rapper occasionally worked, as well as a range of light, sound, and live-image interventions. Norton noted that most of the content seemed to function as “a supplement to the development of Arif as a brand rather than a work of art.” He further criticized that the exhibition did not relate to Munch’s oeuvre but appeared to be a “sophisticated product launch.” The show was a popular success and attracted a record of “young audiences.” Norton questioned why the museum couldn’t reach its goals by exhibiting young Norwegian visual artists. This is a lingering concern of my own: that the public museums have gotten so prone to applying commercial tactics above having confidence in artworks or unexpected curatorial concepts.

The critic and Norwegian editor of the Nordic art journal Kunstkritikk Stian Gabrielsen tells me he thinks that Oslo’s museums are plagued by risk aversion and sameness: “I see a general lack of ingenuity and playfulness.” Gabrielsen points to reasons behind this being a cultural policy shift across the political spectrum over the past decades that incentives museums to prioritize communication and the generation of measurable values: “I think this has to do with a culture-wide imperative to increase the influence of administrative bodies over the way publicly funded institutions spend their resources.” Gabrielsen also ties it to a devaluation of aesthetic complexity, driven by general information fatigue, and sees a politicizing of programming, where exhibitions call upon a sense of moral urgency around certain issues typically revolving around the environmental crisis, marginalized groups, and postcolonial thought: “To be clear, I have no objections to these themes per se – my point is that in the current climate their perceived moral urgency can stymie the creativity of those who are tasked with organizing exhibitions. All these factors seem to collectively drain the exhibition form, and the curator, of energy.” While political issues can be highly generative for curatorial work, when these topics are imposed from different sides, but watered down by the organizational processes and requirements of exhibition-making, the results risks appearing diluted or not genuine. The opening exhibition at the National Museum, for example, under the title “I Call It Art,” showcased around 150 Norwegian or Norway-based artists who were not already represented in the museum’s collection. Works of different mediums were hung closely together, and mirrors reflected the already dense visual noise of the space. The exhibition was an attempt to address the question of what and who is excluded from a collection, but in the end, it appeared convoluted and without sufficient curatorial care for the works and artists presented.

While the National Museum and MUNCH are changing the institutional dynamics in Oslo (Nam is now the largest museum in the Nordic region), they also contribute to a newfound and increasing interest in the city internationally. Together with the Astrup Fearnley Museet, the Oslo Opera House, and the new public library, they comprise cultural and architectural attractions with the distinct and deliberate character of spectacularity by Oslo’s waterfront – baiting tourists en masse, especially after the weakening of the Norwegian kroner. Solveig Øvstebø, the director of Astrup Fearnley Museet – now the city’s only museum dedicated exclusively to contemporary art – says that the expansion of the flagship museums in Oslo has undeniably spurred renewed public interest in art and attracts international audiences, but she points to how this also has its challenges: “For me, institutional flexibility and remaining artist-centered is key. In an art world preoccupied with scale and attendance metrics, museums risk losing sight of their core purpose. Our audiences are crucial, but an overemphasis on visitor numbers can lead to attempts to make art more ‘manageable,’ diluting art’s complexity and challenging qualities.” Since taking the post in 2020, Øvstebø has put on shows with the artists Synnøve Anker Aurdal, Nicole Eisenman, Frida Orupabo, Leonard Richard and Cauleen Smith, amongst others; the program has had a great sense of timing and intelligently managed to create a dynamic dialogue between Norwegian and international positions. The role of giving Norwegian artists their first museum survey was something the old Museum of Contemporary Art had a part in – before closing its doors in 2017. In May this year, the National Museum opened what it’s advertising as the first exhibition in the new building with a contemporary Norwegian artist (A K Dolven) – a fact many people in the scene believe the museum shouldn’t be proud of, because that means it hadn’t done so sooner.

Artist-Run Vibrancy

The streamlining of exhibition-making in the large public institutions in Oslo and the reduced muscle of the mid-sized ones contrasts with the energy of the artist-run scene. Øvstebø highlights its importance and describes the current moment as a vibrant resurgence, “reminiscent of the fertile 1990s and early 2000s” ; Gabrielsen calls it “glimmers of hope on the margins, where a more playful and desire-driven approach to artistic and curatorial practice persists.” One of the agents in this part of the field who has been highly active over the past years is Kristoffer Cezinando Karlsen, whose Borgenheim Rosenhoff has hosted and organized a number of exhibitions and parties in two different industrial spaces on the outskirts of the city, often presenting emerging artists as well collaborations with spaces abroad. Norwegian artist Mickael Marman, who recently returned to Oslo after 15 years abroad with his nomadic space bbberlin, brings up the artist-run scene’s vitality and willingness to bring in an international view. “Both Borgenheim Rosenhoff and Centralbanken are doing a particularly good job,” he says. Hedda Grevle Ottesen, who runs two smaller spaces, Podium and K4, tells me that this energy is partly possible due to public funding (from both the state and city), which lets these spaces remain non-commercial: “It’s quite easy for new establishments to pop up from nowhere, and we see solid artist-run spaces come and go. I like the idea of different spaces that build a scene, have momentum, and then – poof! – they die. This makes Oslo’s scene eclectic. It’s a restlessness that goes in waves.” This restlessness has its downside: Artist-run spaces, as the city’s artists’ studios, often occupy temporary empty spaces and operate within a larger framework of gentrification in Oslo. Paired with the current downgrading of visual arts within both budgets and public opinion, as well as bleak prospects if there were to be a government shift in the coming election , these spaces are balancing on a thin line, highly susceptible to being pushed out of the city’s infrastructure both literally and discursively. Circling back to Hammer’s exhibition “The Workers”: During the exhibition period, Karlsen’s Borgenheim Rosenhoff was invited to have a strange pop-up in a small wooden shed right outside the museum. It hosted various aberrant concerts and events without any clear explanation – in line with the exhibition itself, which, as if resistant to the over-communication of today’s institutional reality, made visitors work quite hard to make connections between the different elements in it. Reflecting on the show’s themes today, Hammer arrives at a concerning conclusion: “In one sense it’s perhaps simply so that we’re seeing the collapse of the previously privileged Norwegian welfare-state model for the art world. It only took 20 years from Elmgreen & Dragset’s exhibition ‘The Welfare Show’ at Bergen Kunsthall, but now it seems like we’re finally here.” Only time will tell if this stark prediction turns true, but the connotation to entertainment in the exhibition title now appears to have been a prophecy.

Live Drønen is a writer and curator based in Oslo. She currently works as the assistant curator at the Kistefos Museum, Jevnaker. She holds an MA in contemporary art theory from Goldsmiths, University of London, and has a background in journalism and media studies. Her work has appeared in outlets such as Kunstkritikk, Artforum, and Various Artists. In 2023–24, Drønen held the position of interim artistic director at UKS (Young Artists’ Society) in Oslo.

Image Credits: 1. Public domain; 2. Courtesy Haugar Art Museum, Øystein Thorvaldsen, 3. © Kunstnernes Hus, 4. © Munchmuseet/ Ove Kvavik, 5. courtesy Nasjonalmuseet, Frode Larsen, 6. courtesy Podium, Erik Mowinckel, 7. courtesy Borgenheim Rosenhoff, Lea Stuedahl

Notes