UNLEASH THE DOLLS Marie Arleth Skov on Penny Goring at Galerie Molitor, Berlin

“Penny Goring: Chronic Forevers,” Galerie Molitor, Berlin, 2023, installation view

The work of London-based artist and poet Penny Goring is painfully private. I am not sure, as I enter the somber rooms of Galerie Molitor in Schöneberg, if I am needed here, if it is actually necessary to finish the message transmission between artist and viewer. These works seem to live on their own. But oh, what a privilege, that I can be here, that these intimate and fierce works are finally on view in Berlin. The exhibition Chronic Forevers presents the latest iterations of the visual output that Penny Goring has developed since the 1980s. The core of the show consists of ten acrylic paint-on-paper images from her ongoing Amelia series and thirteen of her Forever Dolls (all 2023).

“I explore themes that are close to me. That covers quite a lot of ground. I’ve experienced lots of highs and too much rock bottom gutter-level traumatic, dangerous, death-bringing, emotionally abusive and actual physically violent lows. I lived reckless until I got sober,” Penny Goring said in an interview a few years back. “I’ve lost a lot of friends and most of my lovers – these people are still with me in strange ways, and I honour them, use them, make them work with me.” [1] This seems to be particularly true of the Amelia series: “Amelia” is Penny Goring’s alter ego and at the same time stands for people the artist loved and lost, people with whom she still feels connected. The series began in 2017, with the fatal heroin overdose of one such love; over time it evolved into a visual mythology, while also developing materially from ballpoint to felt-tip pen, then to acrylic. [2]

The Amelia pictures look like fairy-tale illustrations: carefully executed, symbolic, strange, somehow both cute and cruel. One image, with the title Double Suicide, shows two naked women, hair black as ebony, strangling themselves while lying entangled in a straggly bush of rosebuds, soon to be forever Sleeping Beauties. Another image, Curse Flower Mountain (Heavy Sky), shows a naked woman, wrapped over herself in a knee-to-chest position, blue lips, red feet, seemingly about to be squished between earth and sky.

The figures are freaky and fragile, sad and violent. Their agony is breathtakingly real, their settings dreamingly unreal. When Goring talks about the recurring motifs in her images, she gives them names, like “the butt roses” and “the grief flowers.” [3] Dark humor flows through her oeuvre. While her work is soaked in hurt and anxiety, it is full of strength and empathy, too.

Goring works with cheap, accessible materials: reused fabric, spandex, salt dough, food dye, or if digitally, with free computer programs such as Open Office. She doesn’t work in a studio, but from her bedroom. “I only want to make things that I can do in my room, with no help from anyone else. I like to think that I’m slyly poking fun at the big boys and grand gestures,” [4] she told the Guardian.

Penny Goring, “Double Suicide,” 2023

Born in 1962, Penny Goring grew up in a tough neighborhood in southeast London. Feeling like a misfit, odd and alone, she skipped school to avoid company. Like so many outsiders, she felt saved by David Bowie, joined his fan club at age nine, and went to see him play at Earl’s Court when she was ten: “He showed me that there was another world, apart from this harsh, scary place where I was getting beaten up.” [5] Turn and face the strange. She began creating, writing.

Goring is the same generation as the “YBAs,” the Young British Artists. Sarah Lucas was born the same year as she was, 1962, and Tracey Emin one year later, in 1963. Goring’s work exhibits a raw intimacy like Emin’s provoking revelations, and her weird bodily figures relate to Lucas’s abject-feminine dolls. The artwork of these three women surely seems kindred in spirit, though both Emin and Lucas do seem more transmission-conscious. For decades, Goring showed her work only to herself, her daughter, and close friends. She graduated in 1994 with a BA in fine art from Kingston University, London, even though that info seems beside the point. She never felt comfortable in the formal art world, considered it too posh, too schmoozy. Her first public institutional show was at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London in the summer of 2022, at age 60. Being an artist is not a career choice for Goring; she does not work for the purpose of display, but compulsively. She makes art because she must.

Chronic Forevers at Galerie Molitor is Penny Goring’s first exhibition after that ICA retrospective and her first in Germany. It is a concentrated show, which relies on – you might write, trusts – the art (and rightfully so). In and of themselves these artworks force your eyes open. The calm presentation at Molitor suits the works: black frames, natural and neon tube light, béton brut.

When entering the world of Penny Goring, the old 1970s slogan “the personal is political” becomes more than a societal, organizational argument; the motto becomes self-evident, accusatory, a slap in the face. The intimate honesty of Goring’s art shows the abyss of poverty and neglect. In Penny’s tale, the crassness of UK austerity politics of the last decades cuts sharp like a knife. This political aspect of her work manifests intensely in her use of words: in her poems (two collections, Fail Like Fire and Hatefuck The Reader, were republished by Arcadia Missa in 2022), as well as in the writing that forms part of her visual art, from the evocative titles she gives her works to the letters she writes across her digital posters or embroiders onto her various dolls.

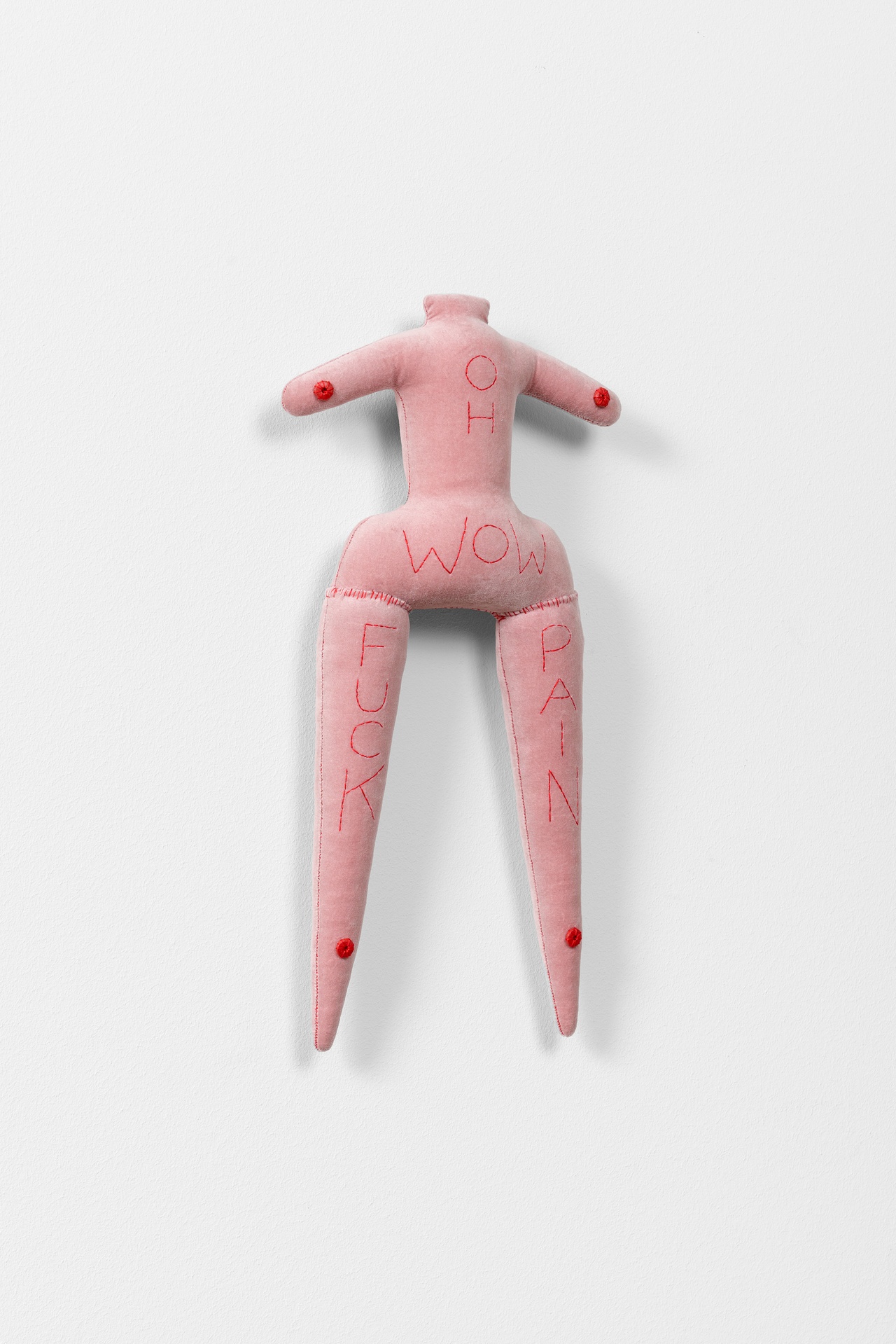

At Molitor, her Forever Dolls hang in the basement, their soft, satiated plushness contrasting the bare grey of the concrete wall behind them. I want to touch both: the cold (I feel) concrete; the fluffy-warm (I imagine) fabric. I can almost sense them in my hand. Good art will do that to you – can make things felt.

“Penny Goring: Chronic Forevers,” Galerie Molitor, Berlin, 2023, installation view

Penny Goring’s dolls are embroidered with needlestick messages: on the grey one, “forever open arms”; on the turquoise one, “we was wild lies”; on the pink one, “oh wow fuck pain,” on the white one, a simple signal-red “NO.” Goring likes to make the process arduous for herself; the dolls are handsewn with a tiny needle. They are headless and handless, forced into open position, broad hips, stretched arms, pointed stumps, ending in no feet. The limbs of the dolls are stuffed full, almost bursting. Voodoo dolls are stiff like that. Goring uses colors to the full: the green is deep dark, the brown is golden, the white is like snow. The accessories stitched onto the dolls taunt the eye: tiny pieces of faux jewelry, small lace thigh garters, cheap mini-pearls, and synthetic silk ribbons. In the middle of this row of dolls hangs the royal red queen. Double in size compared to her cohorts, she seems the leader of the gang. On her torso, pelvis, and legs the message Is sewn: “For / ever / murder In my heart / love♥ in my hands”. Dolls represent a long-burning cultural issue, most recently reiterated due to the curious mix-up of the hyper-consumerist and truism-feminist blockbuster movie Barbie (2023), directed by Greta Gerwig. Dolls are proxies; they are fetish objects onto which ideals, fears, and wishes are projected. Dolls have always been a teaching instrument too, showing small girls how to emulate role models of perfect wives and mothers. While playing, we wonder and plan what we might become. Pink dreams, plastic-fantastic, emancipated?

The surrealists knew the atrocious attraction of dolls. Think of Hans Bellmer’s doll sculptures from the 1930s or Frida Kahlo’s painting Me and My Doll (1937). Goring’s work has something surrealist to it too – in the combination of flamboyant precision with deeply dark content and visual terror. Her textile work calls to mind, more than anyone else, Louise Bourgeois: poetry made manifest, scary, beautiful, aberrant, figures with bizarre proportions. Like those of Bourgeois, Goring’s strange bodily works channel awkward, messy feelings with both warmth and horror.

Penny Goring, “Pale Pink Forever Doll,” 2023

For the show at Molitor, Goring wrote about the Forever Dolls: “in essence they are velvet poems – together they form a chorus – apart each sings its own song. Placed centrally, cherry red double forever seems like an avenging angel leading her chronic army – I can see all 13 of them swooping from the wall – holding the line – gliding towards you – serenely but deadly – to battle with worser world.” [6]

Max Ernst wrote of a hundred headless women in La Femme 100 têtes, his first surrealist collage novel, published in 1929, in which he altered 19th-century illustrations into uncanny surrealist collages. Ernst and Goring both make use of old-fashioned visualizations, steeped in tradition and memory, but they change the formula and release the (splendid!) strangeness and inherent carnage of the original image. Although I suspect Penny Goring’s 13 headless women could take down 100 of Ernst’s on any given day. Goring depicts the female gender with ferocity.

Beyond (or inside) “A Room of One’s Own” (Virginia Woolf), Penny Goring (just like Frida Kahlo or Louise Bourgeois) creates A World of Her Own. An artistic cosmos, full of inner meanings and symbols repeated across bodies of work. What Goring has in common with artists such as Kahlo and Bourgeois is the creation of a unique and sometimes terrifying, bloody but also healing, artistic cosmos. Personal trauma turned into art. Hers is a satisfying reminder of the explosive power of poetry and art (and Bowie) let loose. Of poetry, Goring once said: “I reckon it could save us if we let it off its leash. Unleash it. Let it rip throats out. Those throats that need ripping. And let it save those of us who need saving.” [7] I imagine her army of Forever Dolls would do just that, fighting evil with evil, saving with mercy – once unleashed from the gallery wall.

“Penny Goring: Chronic Forevers,” Galerie Molitor, Berlin, September 7–November 11, 2023.

Marie Arleth Skov is a Danish art historian, writer, and curator living in Berlin. Her new book Punk Art History: Artworks from the European No Future Generation is published by Intellect Books (2023).

Image credit: All images Courtesy of Galerie Molitor, 1, 2, 4. photo Marjorie Brunet Plaza, 3. photo Julian Blum

Notes

| [1] | Penny Goring, “tower block 55: a poem by penny goring,” interview by Sarah Roselle Khan, The Fifth Sense, i-D, 10 June 2017. |

| [2] | Conversation between Marie-Christine Molitor and the author on October 5, 2023. |

| [3] | Ibid. |

| [4] | Penny Goring, “Artist Penny Goring: ‘David Bowie showed me that there was another world,’” interview by Hettie Judah, Guardian, June 21, 2022. |

| [5] | Goring interview, Judah, 2022. |

| [6] | Statement by Penny Goring provided by Galerie Molitor, October 2023. |

| [7] | Goring interview, Khan, 2017. |