With its clean white, the windowless skylighted gallery room is aesthetically not far removed from the interior of a medical facility. Moreover, public art and health care institutions in the UK both find themselves in critical condition following economic developments in the country over the last few years. Abbas Zahedi interlocked these different spaces in his recent show at Nottingham Contemporary by bringing machines and practices of life support into the gallery. While creating space for care and contemplation, the artist also incorporated an impending risk into his show: if the hospital from which Zahedi loaned his central exhibit – professional extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) equipment – needed it, medical necessity would have pulled the plug on “Holding a Heart in Artifice,” as art historian Maximiliane Leuschner details in her review.

Recently, a strategic leadership change took place at Nottingham Contemporary in the British Midlands when, in March 2023, Salma Tuqan took over the reins from Sam Thorne. As an art critic, I’m particularly drawn to the exhibitions taking place on such strategic cusps: such shows mark the outgoing director’s last hurrahs – a carte blanche of sorts. In this case, it also provided us with a taste of what’s to come, as Tuqan and Thorne created this transitional moment together. Foregrounding the notion of grief and its related dynamics (e.g., absence and loss), Nottingham Contemporary’s three recent solo shows – all conceptual in nature – redressed colonized, female, and sick bodies by freeing them from different forms of abuse, exploitation, and invisibility that had been inflicted on their physiques in the past.

Especially in light of recent special reports on the “increasingly perilous state” of the UK’s visual arts sector, weighed down by the triple whammy of Brexit, Covid-19, and the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, it was Abbas Zahedi’s institutional critique, “Holding a Heart in Artifice,” placed thoughtfully in the center of Nottingham Contemporary, midway between the exhibitions “Kresiah Mukwazhi: Kirawa” and “Eva Koťátková: How many giraffes are in the air we breathe?,” that caught my attention. It was a potentially “provocative” placement within the kunsthalle-style institution’s anatomical-heart-shaped ground floor, whose slightly staggered and inter-connected configuration of foyer and exhibition galleries allows visitors to flow through the exhibition(s) like blood pumping through arteries and veins. The middle gallery took on a supportive role and appeared to figuratively sustain both the adjoining shows, as well as the visual arts sector as a whole: For Zahedi hooked Gallery 2 to a humming life-support machine.

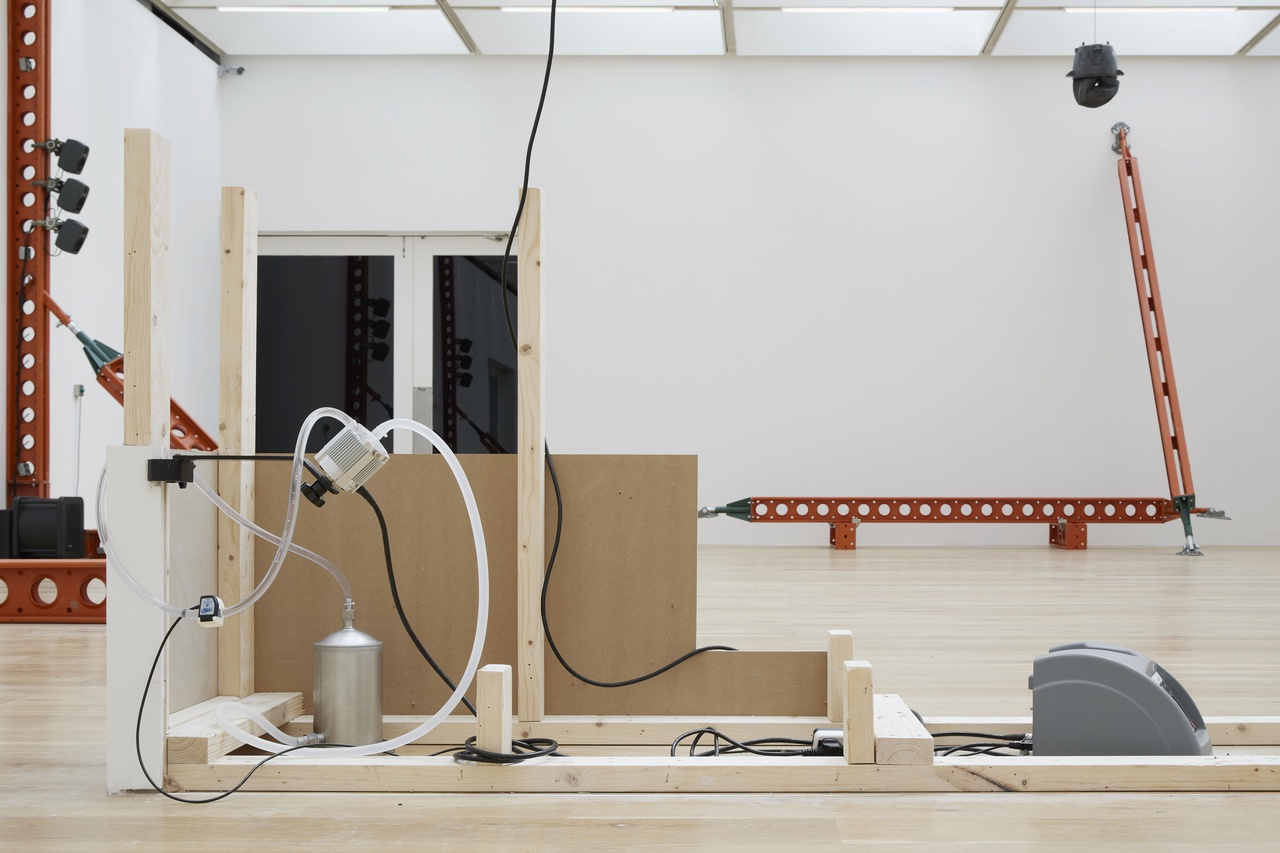

Fifteen burnt-orange and slightly used steel buttresses – forms which usually hold together train stations across the UK, including the one in Nottingham whose ceiling features a white-and-racing-green configuration – were borrowed from the local manufacturer RMD Kwikform for the duration of the show and placed intermittently along Gallery 2’s perimeter. With their perforated structure, they resembled cardiac stents in this context. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) equipment, loaned from the nearby Glenfield Hospital, in Leicester, which is home to Europe’s largest ECMO unit, lay at the heart of the exhibition. Sheltered by an upcycled wooden structure from a previous exhibition, this complex heart-lung life-support machine pumped the gallery’s stale air through its system, replenishing it with oxygen. Yet, like in real life, the outcome of ECMO use was not without risk: per loan agreement, Glenfield Hospital could decide to withdraw the life-saving readymade at any given moment of the show’s duration and, resultingly, cause a premature ending. At the back end of the gallery, a “press-to-exit” button – another staple of British public infrastructure that often graces the exits of all different kinds of public buildings, from offices and schools to gyms, hospitals, and museums, but also public housing, like the Grenfell Tower in North Kensington, in whose vicinity Zahedi grew up – played a spherical music sample, composed by the artist in the style of meditative white-noise music, on command. Nearby, the charred remains of a rice cooker cast in bronze dangled forlornly from the ceiling.

Like all of Zahedi’s site-sensitive interventions in both public and private spaces, “Holding a Heart in Artifice” was contingent on the British artist’s personal path into art – namely, the fact that Zahedi trained as a medic at University College London before pivoting toward the arts by way of spoken word performances, a philosophical colloquium, and community work. He quit his medical studies during his final year, after losing his younger brother to a failed heart transplant. “Narrative re-telling” afforded him the necessary holding environment to anchor his personal and lived experiences in his art and explore new confluences without mitigating or pathologizing his past. Arsalan Isa has described this format as “Dissociative Realism,” which has allowed Zahedi to hone his artistic practice outside of the traditional settings in which art is usually made and shown. For instance, he intervened in public and quasi-public spaces like the basement of a chip shop (Fishbar Symposium, 2010–15), a nomadic pop-up bar for soft drinks across London (Barbedoun, 2015–17), or even the busy Hyson Green/Radford Road junction in Nottingham (Sermons, 2018) to stage institutional-critique-worthy propositions for a reformed art world.

Yet, Zahedi didn’t eschew institutional settings in the process. He did, however, use them to stage interventions, primarily through gestures of visibility or expansion. While invited to respond to the 2022 “Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945–1965” show at the Barbican in London as an associate artist, he expanded the institution’s brief and asked fellow artists to join his public program, “Age of Many Posts.” The residency metamorphosed into a public forum to discuss the notion of “post” in postwar, especially in light of the art market’s “postwar/contemporary” category and its implications for our institutional understanding of art after 1945, and prompted the artist’s reflections on the notion of “contemporary” in Nottingham Contemporary’s name. As such, “Holding a Heart in Artifice” presented a continuation of the new format begun at the Barbican. By forgoing the prevalent “ethnographic” exhibition format, Zahedi conceptualized a “walk-in” spoken-word performance, dynamic and processual in nature. “Holding a Heart in Artifice” functioned first and foremost as a proposition of what a contemporary art institution in 2023 could entail: a creative environment that honors sustainability and positive risk-taking, engages a diverse audience and provides a communal safe space to gather, eat, drink, dance, heal, and share opinions on a host of current topics. Extensive private and public programs, including not-publicized visits/tours for members of Glenfield Hospital’s ECMO unit community and hospital staff, brought Gallery 2 to life. “A Space for How to” (devised in a monthly succession with the verb prompts Wait, Breathe, Share, and Grieve), activated the healing and communal aspect through a philosophical mediation on waiting, breathwork and sound meditation, a dumpling party, and a writer’s crit on grief. Meanwhile, an open mic at the end of June, as well as Nisha Ramayya’s and Zhuo Mengting’s performances at the closing ceremony, promoted the generation and presentation of new ideas and art.

With “Holding a Heart in Artifice,” Zahedi also initiated a new direction: for the first time in his practice, he worked in a differently transformative way and risked an early closure of the show, in the form of the ECMO equipment’s potential withdrawal due to a patient in need. This gesture echoed the unprecedented museum closures during the Covid-19 lockdowns whilst amplifying the art institution’s function as a living organism, a notion that was first put forward in Clémentine Deliss’s essay “The Metabolic Museum.” In his conversation with Eva Wilson, Zahedi drew parallels between the life-support readymade’s interaction with the stale gallery air and Teresa Margolles’s installation En El Aire (2003) at the MMK in Frankfurt am Main, where the installation’s soap bubbles thrived on water sourced from a morgue in Mexico and then distilled, “imbibing” invisible lives of deceased people in the process. Zahedi referred to this gesture as a form of “re-wilding,” as a reintroduction of grief into the fold of art institutions beyond the well-known tropes of Christian iconography (e.g., memento mori; crucifixes) that have existed in the canon for centuries and of institutionalized grief’s place in our society and cultural centers. Embedded in this context, the life-support readymade on display in Nottingham acquiesces its medical use for a broader therapeutic function, engaging a real audience (e.g., the ECMO community, as well as other hospital patients and staff, amongst others) beyond what Clare Barlow calls the “fictitious audience,” which is often still prevalent in today’s art institutions and “has been created out of assumptions and expectations about who might be looking, what experiences and identities they might have and what might be familiar or unfamiliar to them.” By way of collaborating with members of Glenfield Hospital’s ECMO unit and hospital staff, Zahedi counteracted this notion. This echoes a similar action by British filmmaker Steve McQueen, who, earlier this year, presented his tribute to Grenfell at Serpentine South, London, following a period of private viewings for members of the Grenfell community. These formats evoked a sense of therapeutical reciprocity or empathy and relayed a safe space to new audiences. Another supportive measure was the fact that, unlike other contemporary art institutions across the UK in times of the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, Nottingham Contemporary’s National Portfolio Organisation status, awarded by the UK government’s funding body, Arts Council England, allowed the venue to offer entrance to its entire temporary exhibition program free of charge, with the option of a three-pound donation.

With “Holding a Heart in Artifice,” Zahedi has thus intuited an institutional critique that, with little means, has made visible the essential and life-affirming symbiotic interplay between an art institution and its audience. While kunsthalle-style institutions like Nottingham Contemporary lend the British art scene a new lease on life, “Holding a Heart in Artifice” has also shown that their success is contingent on the pluralistic voices and explorations of Zahedi and his generation of artists that bring these institutions to life by repeated questioning existing structures of care and confrontation. Zahedi’s unique experience in medicine, art, and philosophy corroborated the observation that care has become political again. Billed as Thorne’s last hurrah, “Holding a Heart in Artifice” was a first step in a new direction, which, moving forward, will hopefully become the norm rather than an exception.

“Abbas Zahedi: Holding a Heart in Artifice,” Nottingham Contemporary, May 27–September 3, 2023.

Maximiliane Leuschner is an art historian and writer based in London.

Image credit: 1–3 Courtesy of Nottingham Contemporary, photo Stuart Whipps

Notes