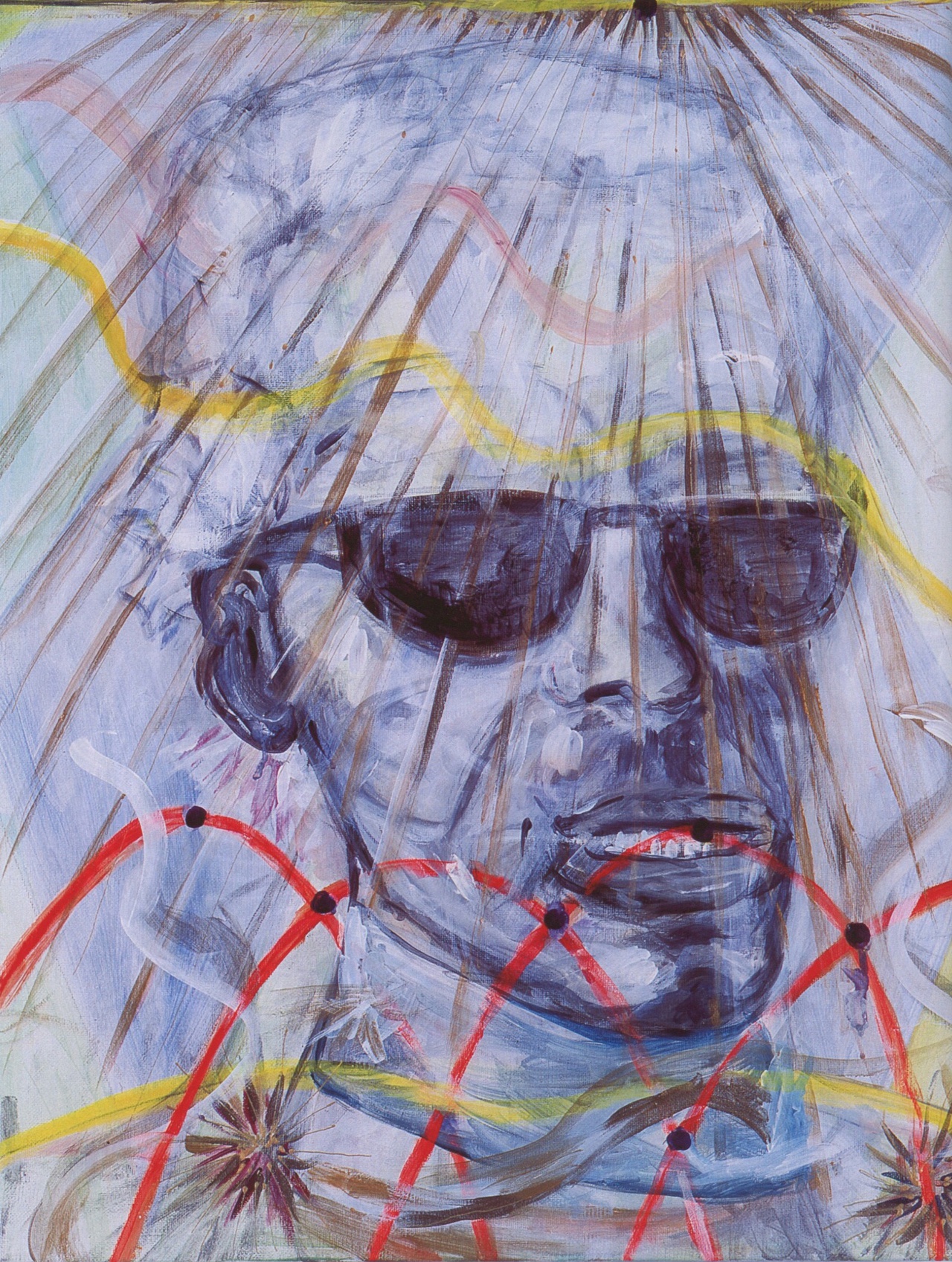

In Memoriam: Karl Lagerfeld (1933-2019) an interview with Jutta Koether

Karl Lagerfeld is currently probably one of the most public personalities. His portrait adorns entire building facades, marking his collection for the Swedish fashion company H&M. What the press has largely called a break with the classic couturier ethos seems to others to be a logical continuation of the Lagerfeld Universe, of which New York-based artist Jutta Koether has long been an observer. And this universe seems to be expanding right now, opening up to include his work as a fashion designer, his stagings, his look, his countless other activities as a photographer, author, and more – such as his work as a photographer.

Jutta Koether’s questionnaire is a kind of letter to Karl Lagerfeld. She tries to trace the rules, the mechanisms, the coincidences, and inspirations of his artistic working process, in which new invention seems always present.

JUTTA KOETHER: I’ve been following your work for many years. I regard the whole “Lagerfeld System” as an artistic work, an unremitting process; a continuous work with huge complexity, peppered with your own commentary; a system always in communication with other systems and thus never frozen, but rather always self-generating, so to speak.

I’ve always wondered: is there ever any doubt in the Lagerfeld Artistic Universe? There seems always to be non-stop reflection; is this built-in? Is there ever a “standstill,” or does the machine run constantly and without interruption?

KARL LAGERFELD: There are doubts, but doubts are like a cold – you can nurture them in this context, if you’re open (lucid) with yourself. Complacency is suicide. Eternal dissatisfaction creates a good climate for discussion with yourself.My life consists of never being satisfied with myself, and I think that this is also the key to a certain (professional) longevity.

KOETHER: Do you feel like a hybrid personality? Formed by systems, but having migrated away from them, or having overcome the system on the strength of affirmation? And now more led by dreams (as was recently expressed in DIE ZEIT)?

LAGERFELD: Such analyses are very dangerous. I do everything with my instincts. I don’t have any pre-prescribed ideas or principles. Rather than dreams, there’s more of a 100%-functioning “sub-conscience” or subconscious. I don't have the slightest feeling of being a hybrid personality. It all just coalesced, just like trees grow. It’s hard to explain and, for me, it’s not important to analyze it in personal terms. I don’t ask myself that question, I just try to find the right answers for myself and my work. Whatever I do, I have a self-confidence built on mistrust. I am merciless with myself and very “distanced” – even if everything is 100% personal.

KOETHER: It’s also mentioned in the Zeit article that even when you were a child, you had the vision of stepping out into the world, of doing and achieving something special (quote: “I always dreamed of Paris and its very special life, and I still do today. So I set off on my path early...”). So do you know where your place is?

LAGERFELD: I had a vision. A deep, childish conviction. I was different from everyone I saw around me (and wanted it like that), and I felt something special was waiting for me – whatever it was and however it was going to be. I was just deeply convinced of it. Less about myself, more just the sheer fact of it. I remember it very clearly. It was like being in pre-life exile. Very peculiar. I can still see the place, the room where I sat and thought about this for the first time. It was around 1945, in Gut Bissenmoor. The old manor house there has been torn down now. I was sat by the big bay window of the “ladies’ room” (as we still used to say back then), at my mother’s writing desk – which was obviously not my place – but I simply loved the adult world, the idea of an unknown, exciting, legendary, bright and faraway place where something good was waiting for me. Maybe I’d read too many fairytales, who knows?

KOETHER: For you, is the extreme affirmation of life, life in the moment, also a motivation to expose yourself to completely new situations, a desire to address new generations, to learn new things yourself – even things that are as difficult as the complete transformation of your own body?

LAGERFELD: It’s very important to think like that. You have to force yourself, otherwise you won’t keep up, you’ll lose your step, and so on. For me that’s simply logical, and it doesn’t require any extraordinary effort. I leave things and people behind if they can’t keep up. When it comes down to it, I understand. But I’m merciless. “Empathy is weakness,” my mother said to me when I was a child. That’s true for me and out there in the world. It sounds tough, but it’s true.

KOETHER: When did you become aware of the extent to which changeability can (perhaps even must) be elevated to a principle?

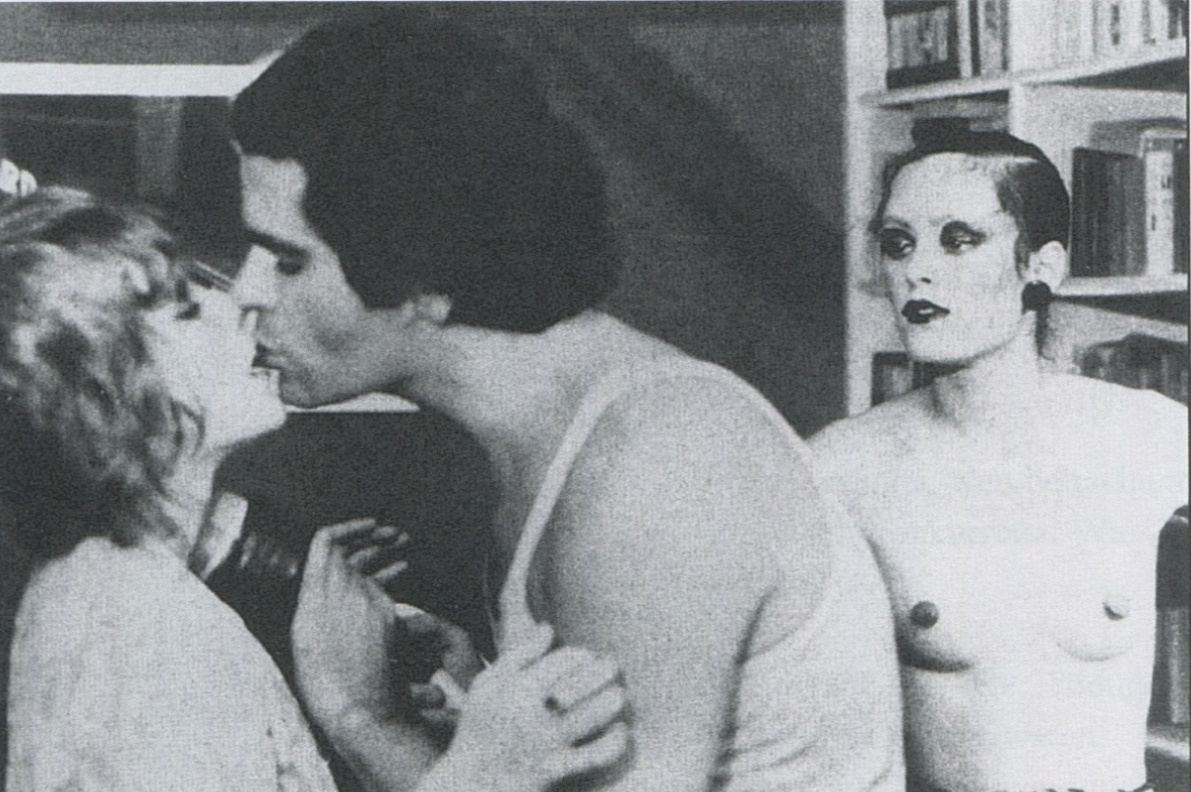

Karl Lagerfeld in Andy Warhols Film „Lamour“,1970

LAGERFELD: It was early on in life that I noticed you can “over-brand” yourself. There’s a certain moment when only a total transformation can change you, otherwise you become “vintage.” A “period piece.” I see myself as a kind of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (without the gender change that occurs in the book etc.).

KOETHER: What do you think of the artist Francis Picabia? Or Andy Warhol’s work and works?

LAGERFELD: I love the work Picabia did from 1915 to 1920. I hate his bad, later painting, but the man must have been wonderful in his day. I knew Andy Warhol well. There are people today who compare me to him, which is ridiculous. My world is a whole world – in his early years, he built a new generation on the ruins of the world and then transitioned over to a glamorous life (which back then wasn’t as dull as People is today). But his work remained wonderful, it kept on evolving and today is much more important than it was in the moment. He tried to avoid being politically correct. That is something that can make today`s world so boring. If you read Interview from 1969 to 1979 – no one today would dare to write or speak in such a way. That’s the difference with our time.

KOETHER: Did you yourself ever have “role models”? How was and is your relationship to Coco Chanel as a figure? And do you by any chance know who was the first to call you the “Kaiser”?

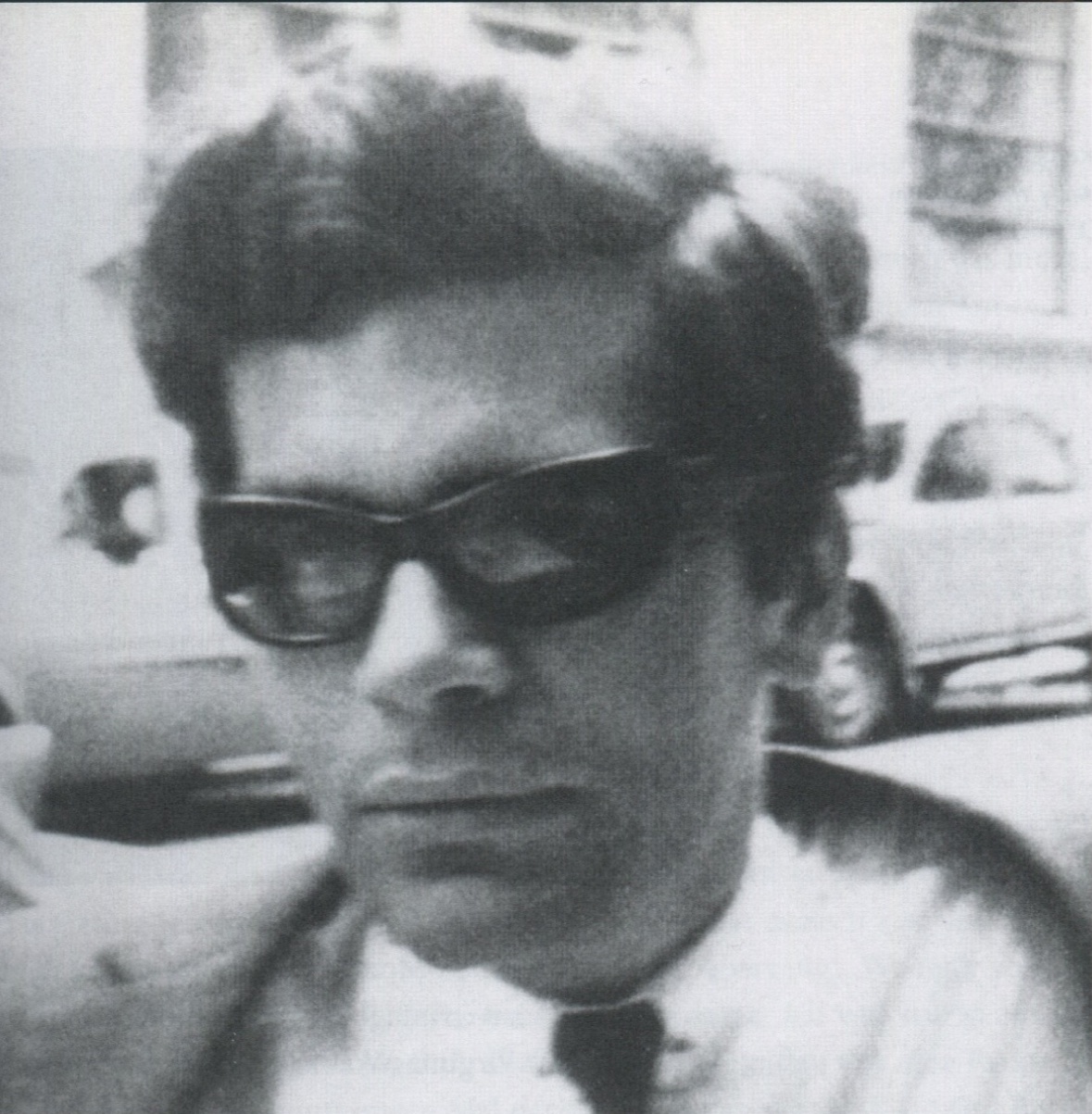

Karl Lagerfeld, Paris, 1960

LAGERFELD: To begin with, I had no relationship with Coco Chanel That wasn’t necessary back then. Back then too, personnage created an extra dimension. What we imagine, and what I liked about her, had maybe nothing to do with reality. Posterity is often more interested in the idea of the thing than the reality of what it was. This applies to people, places, and times. John Fairchild called me Kaiser before anyone else did. Was it a compliment? I`m not sure. Wilhelm II was a bad example of a final Kaiser.

KOETHER: How much chance and paradox is allowed when designing? Is everything you do planned in general terms, or are there moments when something can or even must lose itself? Does this vary depending on the comission/context or the company you are currently working for? Is it the work itself that inspires the work?

LAGERFELD: When there are no rules, it becomes a question of balance. “Inner voices” can help, otherwise it just becomes “marketing.” My motto is “doing for doing,” I forget about the goal and purpose. This is my idea of artistic freedom – as far I consider myself an artist.

KOETHER: You're known as someone who puts work above everything else. Is this a dandyesque form of a Prussian work ethic? Do you sometimes have to force yourself to work or is it always a pleasure? Do you even consider yourself belonging to a species of “international dandy”?

LAGERFELD: That’s the only way it works. People today have a negative vision of the word “work.” I am lucky that my work involves what interests me the most. Probably the motivations you have attributed to me are an unconscious part of it. I am lazy by nature and often find that I lose a lot of time reading and daydreaming. But maybe that’s also important and creative. The term “dandy” is alien to me as far as my personality is concerned. That poor word, that poor man - they’ve had to answer for everything.

KOETHER: Do you have a sense of competition, and if so, who do you consider your biggest competition? Is youth essentially competition? How do you define your relationship with the younger generation?

LAGERFELD: Youth is no longer necessarily competition. Too many “young designers” have proven that they are or were just “young.” Many quickly disappeared again. When I was young, youth was not required, you had to prove that you were good and not just young. Rivalry and competition are stimulating and vital – even if in today’s very capitalist fashion world the “game” is manipulated. But I, Chanel, LVMH (Fendi) etc., and even H&M also benefit from it.

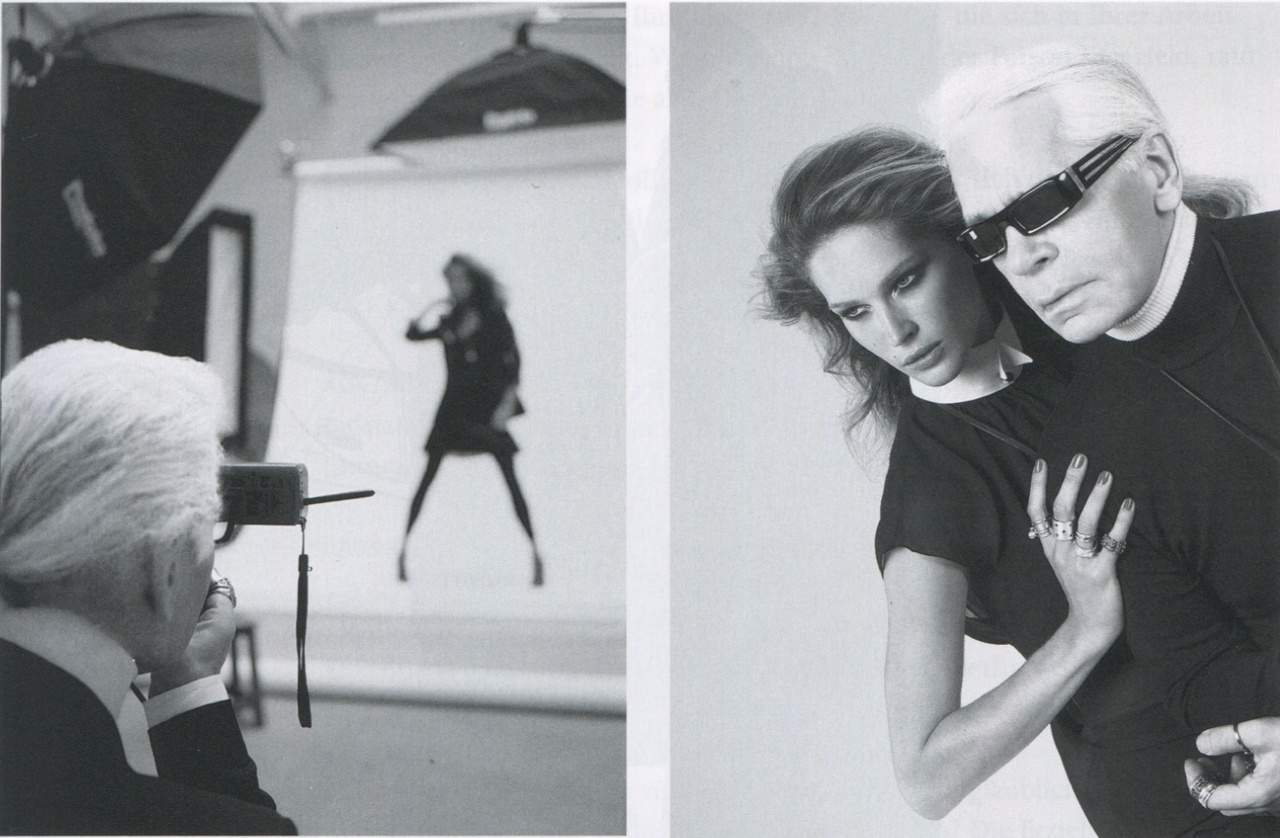

KOETHER: What impelled you to accept the commission for H&M? Did this commission give you a feeling of lightness, that you were able to play a game – even with your own personality, position, and empire? Or how else should one understand the Liquid Karl perfume and the Karl Rockstar T-shirt for €14.90?

LAGERFELD: There’s something true in all of your long questions. At the same time, however, it is simpler. H&M is a fashion phenomenon and someone like me cannot ignore it. Its success was unpredictable and has changed something in the world of fashion and the reception of fashion for many (and also for me). Suddenly we're in the 21st century in terms of the way fashion is spread. “Luxury” must redefine and justify its “position.” Which is ok by me. The middle, the mediocre, must be avoided. I am very happy with this success and would have liked more people to benefit from it.

KOETHER: If one were to see the Lagerfeld Universe as a (dysfunctional) family: what are the interrelations between your work for Fendi, Chanel, Lagerfeld Gallery and H&M? “Haute Guerilla”? I find it fascinating how you design as if there is nothing to lose and everything to win. In every era it’s always rather unstrained – “flung together” designs, rather than “built” ones...

LAGERFELD: I see this question as a great compliment and would like to say 100% yes to you. Even though things may be more complicated, it is part of my job (and my way of doing things) to make a certain sovereign impression of “lightness.”

KOETHER: As a contrast to the ever-changing products of work you spoke about, have there always been absolutely firm symbols? Ones that stand for principles (the hair, the glasses, the stiff collars, the look that is rigorously enforced and that seems to stand as a guarantee of something)?

Anzeigen für „Karl Lagerfeld for H&M“, 2004

LAGERFELD: Is it the statue of my version of the Commander in Don Giovanni? Maybe? People think I’ve always been like this – but it’s not true. Only the impression felt last is important – until the next “expression”... it’s not easy...

KOETHER: There was once a talk show in the eighties, back in the early days of cable television. I tried to find it again, but it wasn’t possible. I remember that at the time you presented a form that seemed to me to be a very original mixture of performance art, lecture, sales show and a kids’ story time. Could it be that this “procedure” in the broader sense still exists? (Now all available media and opportunities are a kind of stage.) I am extraordinarily interested in how you simultaneously jump back and forth between art, architecture, photography, interior design and fashion, while at the same time always being able to make very firm value judgements about EVERYTHING, i.e. the simultaneity of extreme flexibility and values.

LAGERFELD: Life, with my way of living it, is a stage, but if one is to be spontaneous and to not waste the performance, one often has to wait around for a long time in the dressing room or standing around the scenery. I also remember the TV show you mentioned.

KOETHER: What significance does fine art have for you? For you, does such a category exist? Or is that just a question of memory? Do you prefer to look at historical examples in the original or on photographs?

LAGERFELD: Today, catalogues and illustrations are so wonderful that they’re almost enough. You almost don’t need to see the original. All artists, the old, the new, the avant-garde, are “primordial” for me. I want and need to know, see, and learn everything. It’s kind of a ravenous appetite.

KOETHER: More than any other designer, you seem to resist the motto that one should create something and then remain silent. You create and you speak, which then ignites a new idea. Yet you never interpret, just allude, create points of entry. Among other things, you are also a conversation artist. Where did you learn that?

LAGERFELD: This is something I learned from my mother and refined via numerous lessons. I talk a lot so as not to say anything, because I think instead. In Voltaire`s words: “That which needs explanation – is not worthy of explanation...” A wonderful truth!

KOETHER: Do you really only distinguish between people who are bored and those who are not bored and do what has to be done? Your dream of eternal creativity is tied to an uninterrupted eagerness to work, one which seems to include all activities, from dancing to writing books to social commitments. Are there, despite this, any priorities? Even if there are no “distractions” for you, i.e. you work from morning to night, it seems that, in the nature of the work you do and the way you do it, “everything” is in there!

LAGERFELD: That is a tendency of mine. But you have to be one hundred percent behind everything, no matter what you do or how complex it is. That’s my nature. This is a kind of “talent” and predisposition, perhaps... I hope. I do it “effortlessly,” almost naturally. These are advantages that few of my colleagues share. But it is perhaps also a question of education and background.

KOETHER: In one text you said “the meaning of life is life itself.” Is that still true?

LAGERFELD: 100%.

KOETHER: Are you still interested in the 18th century? Was your interest in this what you called your fascination for the “material expression of architecture, painting, and clothing” a kind of matrix for your own work?

LAGERFELD: Yes, it’s somehow part of my way of thinking. “L’Europe des Lumières” is my ideal – not today’s Union without spirit and charm.

KOETHER: Where does your love of uniform come from, a love that is always present in your work? What does a uniform give to the Lagerfeld personality, and what does it give to those who wear it?

Unter den Linden, Berlin, November 2004

LAGERFELD: Uniforms should fit well. It’s about the ones you see in old photos and paintings. They had shine and color. Today they are all a little “dark” and without éclat, brilliance. That’s something I fight against. I hate the military, but I love uniforms.

KOETHER: What did you mean by the phrase “basically, my nature is one of the advisor to the royal court”? What kind of ideas are you driven by? Do you always have confidence in yourself or is there sometimes fear?

LAGERFELD: My mother had two ideal men that she found wonderful and wanted me to take as role models: Walter Rathenau and Graf Kessler. It’s all very “Wilhelmstraße” (especially Rathenau). My mother was a daughter and granddaughter of a high Prussian civil servant. I would have gone to Berlin if there hadn’t been war and the Nazis... “born too late,” she said...

KOETHER: To whom or what do you owe all this incredible self-confidence? Did growing up in material comfort have anything to do with it? Your upbringing? Friends? Do you need positive feedback? Are all your activities part of an ongoing self-realization process, which in turn is an interesting game with self-determination and external determination?

LAGERFELD: I can only answer yes. I owe a lot to my parents, including my well-balanced, almost puritanical, healthy nature, which is not something which is apparent to everyone.

KOETHER: There’s one medium which seems to accompany everything you do – drawing. What significance does drawing have for you? Do you keep all the drawings? Or are they obsolete once they’ve been used? Do you love drawing?

LAGERFELD: Drawing is the starting point. That’s how it starts and often ends. I can draw very well, which helps me to express myself quickly, clearly and unambiguously. A big advantage!

KOETHER: Are you interested in painting? Is there any picture that you have always liked and that has influenced your aesthetic perceptions?

LAGERFELD: Yes, it’s just that the time and talent aren’t there. My influences: Jawlensky, Matisse, Kandinsky, Feininger, all expressionists, Manet and Goya, Poisson, Philippe de Champaigne, and religious painting in 17th century France. I love the 18th century, but painting touches me more in the field of fashion.

KOETHER: Do you prefer to work “analogue,” alone, or in a team? Do you prefer an artistic form of organization, a studio, or rather a company?

LAGERFELD: Both. I prepare alone and then expand on it with teams. Studios within companies, companies as “companies”, it all bores, even in my own companies – except for KL, the shop, and the publishing house.

KOETHER: Is the sentence “you can’t order an idea” also the expression of a certain “ability to leave things open,” the lightness of inventiveness, which perhaps comes from experience but cannot be learned? Is that a romantic idea of creativity?

LAGERFELD: I think you are correct. It sounds wonderful – but it’s not always so weightless as that. The best work is often simply not that which had a difficult birth... Unjust, but true. Here, there’s no such thing as “deserving it.” It’s kind of a happy coincidence when it works.

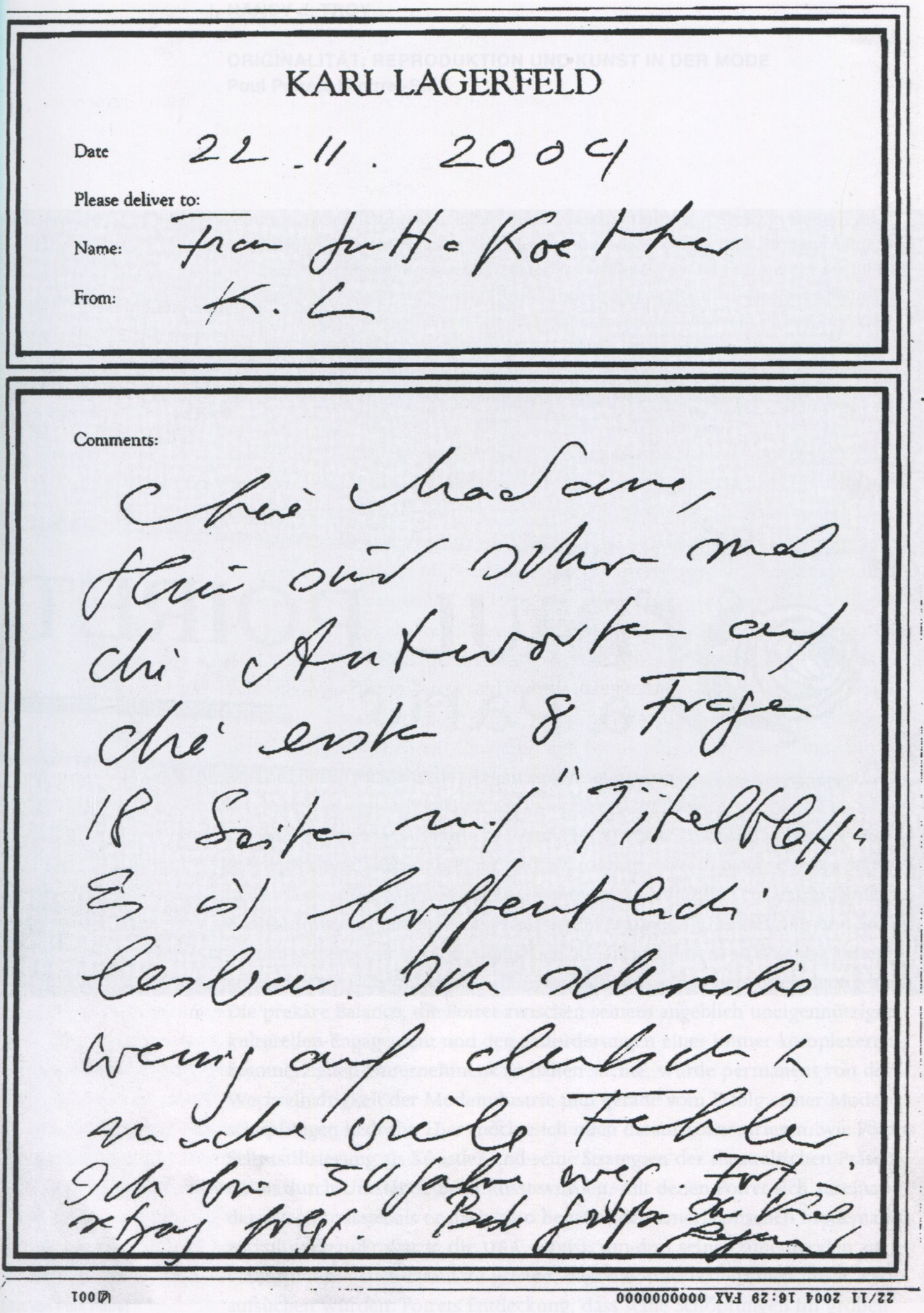

Fax an Jutta Koether

KOETHER: Are you fascinated by the effects of celebrity culture and the effects you produce yourself?

LAGERFELD: Putting it about is part of the craft. It’s true than ever... And fine by me.

KOETHER: In which legal form would you ideally like to exist?

LAGERFELD: I get along well in today’s environment. It’s our time, and we have the time and zeitgeist that we deserve.

KOETHER: Will there be another radical change of style in the near future? Or will it just stay the way it is for a little while?

LAGERFELD: I leave all doors open, come what may. And just what will come, nobody knows. I’m always ready.

KOETHER: Where does the name Lagerfeld come from?

LAGERFELD: I’ve not come across it anywhere in Germany, but I have come across it in Sweden. It’s there in some old papers too, but I don’t really care: “it starts with me and it ends with me!”

Translation: Matthew Scown