FROM PRIVATE VIEW TO PUBLIC EYE Reflections on Making Sexualized Violence Visible in the Art Field with Sabeth Buchmann, Christina Clemm, Iris Dressler, and TEXTE ZUR KUNST

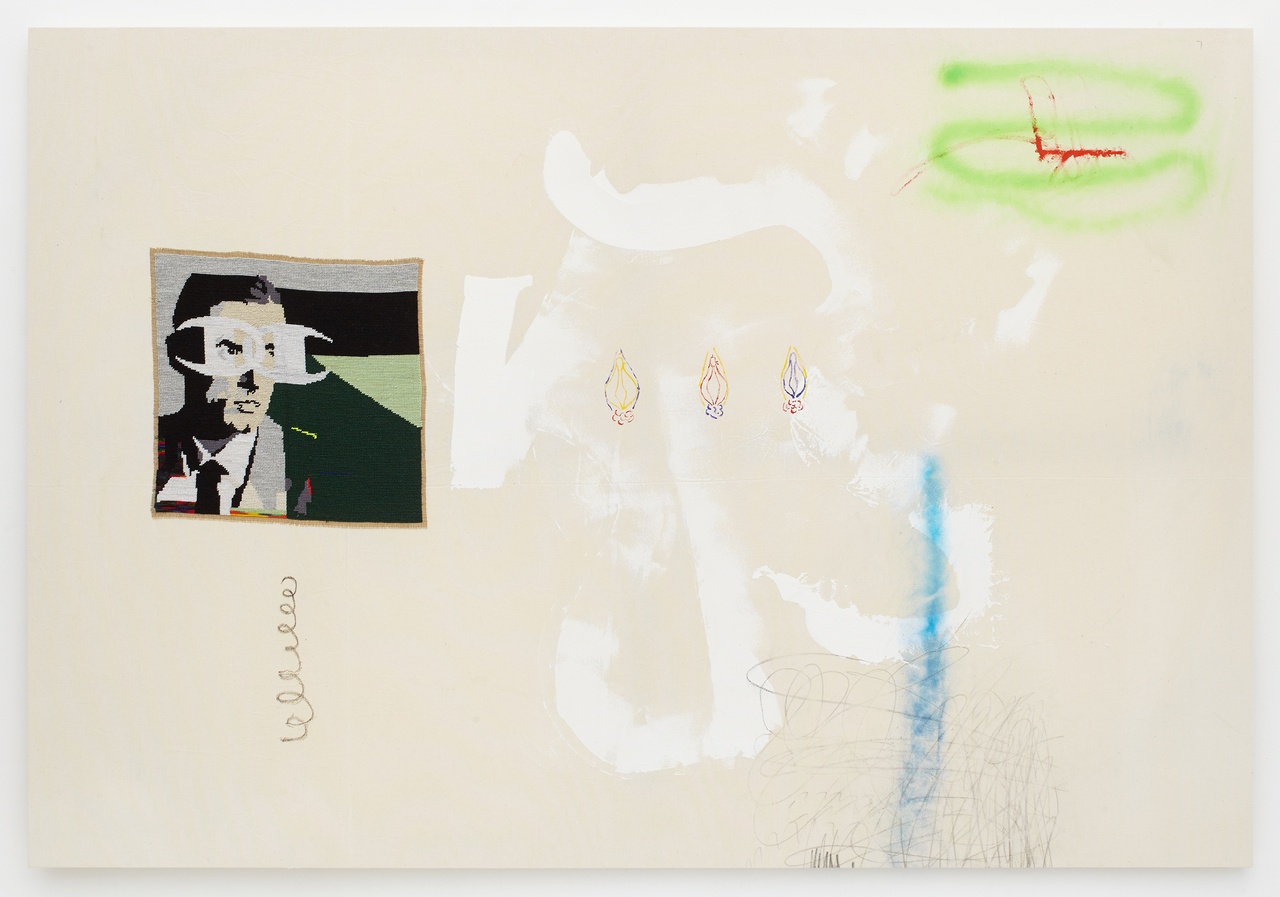

Verena Dengler, „Young male painter channelling Falco gazing at Keith Farquhar’s Neon Vaginas through Chanel-style Champion Logos”, 2015

TEXTE ZUR KUNST: This roundtable was prompted by a discrepancy we have noted in how sexualized violence is dealt with in the art field: while many art-field protagonists are keen to present themselves as progressive and extol the importance of #MeToo, the movement has had comparatively little impact in the art milieu. Any isolated cases of sexual assault and violence that did become public knowledge were quickly forgotten – as were the people who had experienced it. In her recent book Backlash: Die neue Gewalt gegen Frauen (Backlash: the new violence against women), journalist Susanne Kaiser describes something perhaps especially true of the art world: even while the patriarchy is being dismantled in discourse, it continues de facto to exist. And this is precisely the tension, says Kaiser, in which “hatred and violence against women flourish.” [1]

Iris Dressler: I find it interesting how in 2018 ArtReview placed #MeToo third on its Power 100 list – the first time a movement was included in its ranking – arguing that it had now arrived in the art world just like elsewhere, that it was set to really take hold. [2] As you say, back then only a few cases of sexualized violence in the art world had been brought to public light, mostly in the US. [3] The magazine’s power ranking had little to do with reality.

Christina Clemm: Understood as the making-public or making-visible of sexualized violence and power structures in work environments, #MeToo has changed staggeringly little in Germany. I agree with the thesis of Susanne Kaiser’s Backlash: it’s true that there’s a nominally liberal, feminist public sphere where people speak out against gendered violence. But in the cultural sphere, for instance in spaces like the theater, where the issue of gendered violence is addressed pretty often and feminists are represented, there is literally no one looking at what goes on behind the scenes, where harassment is happening. The progress that’s communicated externally is not taking place internally. I’m also seeing a backlash in the legal sphere: for one, there’s an increasing sentiment of, “honestly, enough’s been done already, equality has been achieved” – even though violence is increasing and conviction rates are catastrophically low. And I’m also seeing the Right getting stronger across society, even in the judiciary. Is that something you all are seeing in the art field?

ID: It is certainly possible to discern an increase in violent right-wing attacks across the cultural sector. There’s a project that was recently launched at a temporary space in Stuttgart. It involves artists, queer and anti-racist groups, initiatives by and for refugees, and many others. A little while ago, a group of Identitarians turned up there and set fire to posters. And at our outdoor platform at the Kunstverein, another person intentionally rode their bicycle into an installation about the racist murders in Hanau. As art institutions, we have to rethink how we protect our spaces. But back to the problem of sexualized violence: it’s common knowledge that it’s largely about maintaining power and systems of oppression. And this applies just as much in the art world. Change is needed at the structural level – by looking at the workings and mechanisms of the sector as a whole.

TZK: We’d like to expand on that thought with you all by investigating how far structures specific to the art field – from the education stage to the career stage – are breeding grounds for sexism and sexual assault. Power and capital are markedly imbalanced in the creative industries: leadership roles are mostly occupied by men, while women largely work in financially precarious situations. [4] One thing that seems particular to the art field is that networking isn’t just central to professional success – business relationships actually operate with an extremely high degree of discretion and often flourish in utmost privacy. It’s something that begins as early as the art-school stage. Before returning to the conditions under which education operates, we’d like to ask: Do you see the gendered abuse of power in the art field as ideologically rooted as well?

Andrea Fraser, „Untitled”, 2003, film still

Sabeth Buchmann: The idea of freedom – or of the libertine – is key here. Living the life of Eros is central to this. Feminist artists like Andrea Fraser and Lucy McKenzie have explored this by addressing the structures of desire in art and the art world. And these are structures that they help shape, structures that cannot be so easily eradicated or overcome by individuals.

TZK: Fraser’s Untitled (2003) is a perfect example of the radical approach she takes to her own enmeshment. But in the work’s reception (by men at least), the moment of empowerment that is central to the work quickly turns to disempowerment. Jerry Saltz’s comment about Fraser’s attractiveness would be a good example. [5]

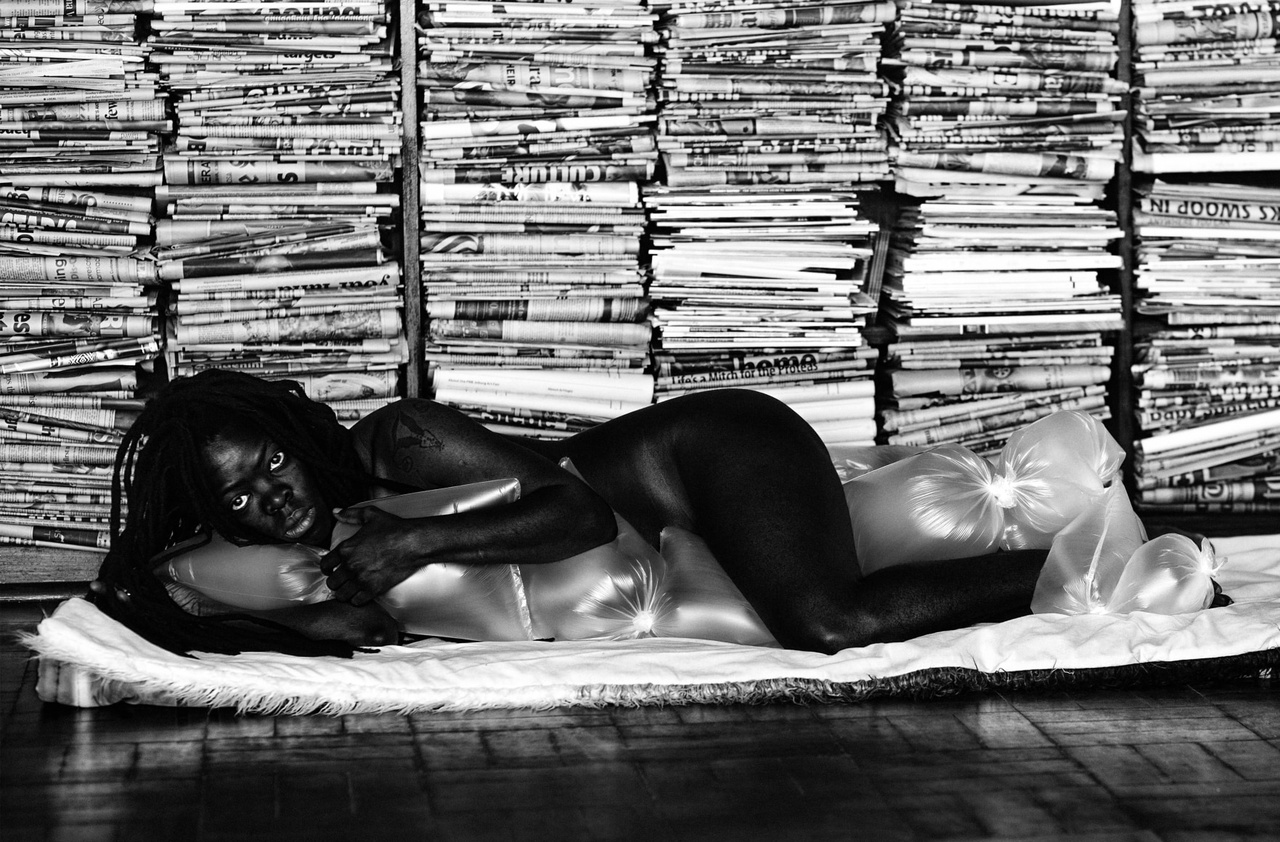

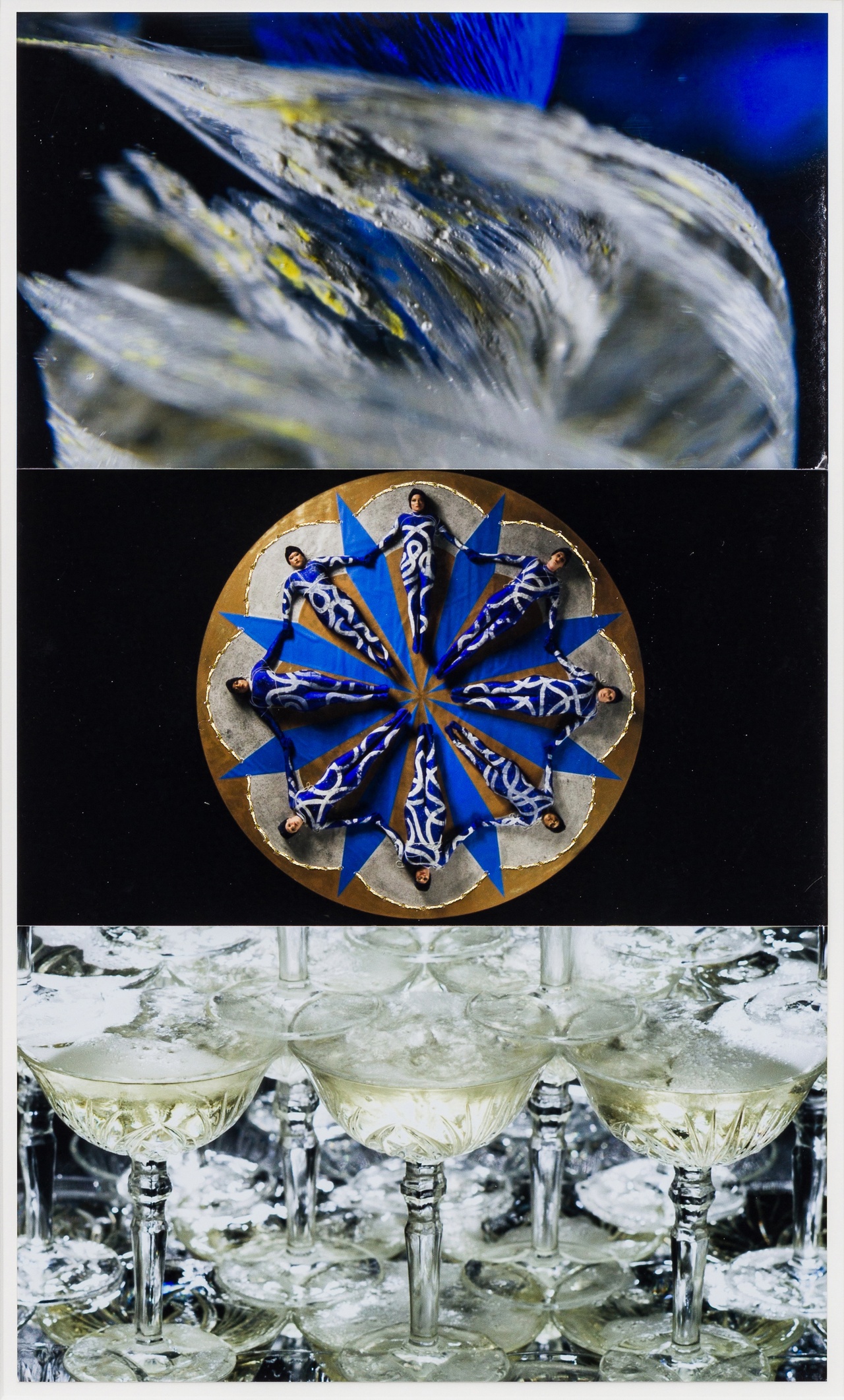

SB: Fraser’s work refers to the explicitly or implicitly sexualized structural relationships in which artist, gallery owner, and collector operate. In addition to this there are modern art’s constitutively sexualized and at times deeply misogynistic tendencies, which reveal themselves in fetishistic iconographies. These have historically often come hand in hand with real cases of abuse – something art history has long knowingly ignored and which has to this day still not been adequately reckoned with. Corresponding modes of representation have become firmly inscribed into art’s imaginary. It seems fitting to assume this is one of the reasons it’s so difficult to break beyond suspicions of moralism, puritanism, and censorship and to actually address the abuse problem at a structural level. This might be one reason why some of Fraser’s works, like Untitled and Official Welcome (2003), address the difficult-to-overcome dependence on feeling desired – and do so at the most acute extremity of discomfort. Correspondingly, it’s largely queer-feminist, non-binary and trans artists – like Yvonne Rainer, Zanele Muholi, Antonia Baehr, Katrina Daschner, and others – that have explored how hierarchical structures of desire can be changed on a formal, aesthetic level. Or to put it another way, they explore how sexuality can be imagined as something that doesn’t function along the poles of power and submission.

ID: In my view, concepts and practices of sexuality and desire involving submission, power, violence, or pain do not necessarily have anything to do with what I would designate as sexualized violence. The central point – but also the most complex and difficult one – is about mutual consent between people engaging in sexual activity with one another. Consensual BDSM – which to my understanding is a deeply aesthetic practice – is centered on boundaries. And dedicated feminist (and queer-feminist) forms were developed to handle these boundaries in a way that critiques power. There are artists like Monika Treut, who picked up on this back in the ’80s. Sexualized violence, on the contrary, maintains hierarchical power over sexuality by consciously violating the boundaries between the consensual and the non-consensual. Adina Pintilie’s film Touch Me Not (2018) was the start of a collective research project on non-binary and non-normative forms of intimacy and sexuality, addressing the hierarchical power structures of the film industry. [6] Right from the start, one of Pintilie’s key motives was to experiment with participative forms of collaboration between the filmmaker and the film’s diverse protagonists, who worked together with her on the long development process. Among other things, there was a “panic room” installed on the film set as a safe space.

Elfi Mikesch and Monika Treut, „Verführung: Die grausame Frau / Seduction: The Cruel Woman”, 1984, production still

SB: Feminists articulating their own enmeshment in sexualized or sexist visual language and forms of desire is something that has to be clearly demarcated from sexualized violence.

CC: And that demarcation is also important because of how often violence is palmed off as desire. Violence can thrive especially well in disguise. So it’s important to ask, what’s really at stake here? Sex or power? When we talk about sexual desire, whose desire are we talking about? Who is playing out what desire? So – is sexual violence actually about sexuality or is it, as I believe, a form of degradation enacted using sexual means?

SB: You’re absolutely right – we have to make clear distinctions if we also want to examine the gray areas – such as common demonstrations of power and “recognition imperatives,” to conflate a few phenomena Isabelle Graw discussed in relation to the art market.

CC: If I as an outsider to the art world could add something here: I don’t believe at all that it’s so different from other realities. Women who speak up about the sexual harassment they suffer, even about physical assaults, always get the same reaction: “It wasn’t meant like that,” “she just took things the wrong way,” “she loves it really.” Perpetrators make creative excuses, people believe them. Even beyond the art field, victims and opponents of sexualized violence are accused of suppressing desire, of being unerotic prudes, having no creativity, hating freedom, whatever. It might be the art world’s celebration of Eros as a creative force that has made such accusations particularly prevalent there, but it exists in modified form everywhere. Demanding respect for boundaries is constricting, transcending them is creative. But this is of course only true for perpetrators: it’s about their freedoms, not about everyone’s freedoms.

ID: What really sets the art world’s power structures is a distinctive lone-warrior mentality that secures itself through an “old-boy network” that has actually long since ceased to consist solely of white cis-hetero men. Anyone challenging the unwritten rules of these structures – especially the codes of silence about abuse – faces a lot of friction and is at risk from threats. I experienced this myself after going public on a case of censorship. [7] “We deal with this kind of thing behind the scenes,” some of our colleagues told us. And in all this I noticed some parallels to the way sexualized violence is dealt with – victim-blaming, for instance. One claim was that the artist had brought the censorship on herself. The man who tried to censor the work, on the other hand, was said to be an innocent and universally respected colleague, so the accusations couldn’t possibly be true. On many levels, the art world operates by concealing power structures and conflicts, on a basis of fear and high psychological pressure.

Zanele Muholi, „Julile I, Parktown, Johannesburg”, 2016

SB: This phenomenon is, unfortunately, still not being tackled in a way that can genuinely, sustainedly affect change in the social structure of the art world. Apropos – I feel like acknowledging the problem, both in the art field and beyond, means also recognizing the collective traumas of cis and trans women and non-binary people, of lesbians and queer people. These are people who haven’t just had and continue to have hurtful experiences – they also sense and know that articulating them is extremely painful. This reinforces an already-existing sense of powerlessness, of Ohnmacht.

CC: This turning a blind eye is also collective. Everyone knows who is prone to commit abuse – and everyone turns a blind eye.

TZK: Last summer, Die Zeit published anonymous accusations made by several alleged victims against the Berlin gallerist Johann König, [8] but once again this didn’t lead to any base-level discussion. In Die Tageszeitung, the journalist Sophie Jung described “something of a sigh of relief. The accusations,” continued Jung, “had been in circulation for a number of years, with König’s lawyer’s initiating proceedings against them just as long.” [9] Art magazines like Monopol and Artforum didn’t go any further than brief news reports and provided no analysis of the case. We have also not spoken on the case. The publication organs of the art field – we included – do not exist beyond the field’s networks and their power structures. To provide an example: such publications are situated in positions of financial dependency on art-market stakeholders. Which is far from secret – it’s readily apparent.

SB: Though not in printed form, there were quite a lot of reactions to the case. They were astonishing, I felt. On some sides I’d hear, “it’s great and absolutely right that it’s finally coming to light,” on other sides “oh come on, it’s just an isolated case,” but also “it’s not just about Johann König, you could also name 50 others at the same time.” One of the critiques I’ve heard from feminists is that this approach doesn’t address the structural power relations. The “where do we start” question is typically followed by “none of this is enough.” And sooner or later, the collective, combative spirit just fizzles out.

TZK: But where do we start? Do you have any ideas on what underlying conditions need to change? What policies are needed so that people – even ones in precarious situations – can take the first, vital steps toward visibility and talking openly about the issues?

ID: I think we need to start building institutional-level structures and networks that offer victims and other affected people a suitable framework for protection and trust. This would also involve building a database of all the already-existing support points and counselling centers. There’s the example of the model project Fair Stage, launched in 2021 by the Berlin Senate Department for Culture and Europe. It joins up all the existing structures in the performing arts and uses that as a basis for developing guidance. [10] Things are still a bit more sparse in the art world. In 2020 the Baden-Württemberg Ministry for Science, Research and Arts appointed an ombudsperson for sexualized discrimination, sexual harassment, and violence, for instance. All institutions funded by the ministry can call on her. And as far as I know, BBK Berlin [a Germany-wide professional association for artists – Translator’s note (TN)] is working on models for freelance artists who aren’t protected by equality law. But it’s not just about protection and trust. It’s also about transparency and about making sexualized violence a political issue. We need safer spaces that generate awareness and solidarity, but which also allow people to stay anonymous. How can visibility and anonymity, protection and politicization be brought together? On the subject of sex work, Petra Bauer’s film Workers! (2018) did this impressively on an aesthetic level. But if sexualized violence remains an open secret, that says a lot about the unresolved power-political relations of a community.

Petra Bauer, „Workers!”, 2018, film still

CC: I’m also a big fan of counselling centers that are easy to access and offer full anonymity. They have to be absolutely diligent in acting in the interests of victims and with their consent. There’s cases where instead of aiming immediately for a public hearing, it’s proven worthwhile to send out an offer of dialogue, maybe to confront the accused, even just to talk. Grievances can be addressed at an early stage, before major consequences arise. Counsellors have to be well trained for this, and the offices also have to be well equipped. They need funding and proper capacities if they’re going to be able to do their work properly. This can’t be something they just offer on the side or that women’s representatives [special commissioners for women’s issues in Germany – TN] just take on as part of their normal roles. And work with perpetrators is needed, too. One key thing is to finally stop treating sexualized violence as just a women’s issue. We have to talk about concepts of masculinity, about violence and dominance. The current discourse only reacts to scandal. But there’s no discussion about the perpetrators, nor about the structures that sustain and protect them. We talk about victims, how there’s an incredible number of them and how they should behave. But we don’t address the questions of who the perpetrators are, how they act, and why they don’t stop. There are hardly any services that work with perpetrators, no voluntary or compulsory courses. Perpetrators are tolerated until it’s no longer sustainable. And if someone speaks out in public about a perpetrator – well, ideally if several people do so – and it becomes impossible to turn a blind eye, then the approach is to make sure the individual perpetrator just disappears and the scandal gets brought to a close as quickly as possible. There’s a lack of ideas on how to intervene at an earlier stage, either institutionally or personally. For me, this is about a culture of looking closer, of drawing attention to problematic behavior, and intervening. Because why do sufferers always have to come forward when everyone else knows what’s going on too? How come everyone always knew, but no one said anything? The fact that even people not affected remain silent makes it pretty obvious how difficult it is for people affected by abuse to openly talk about their experiences of violence. My point isn’t that decisions should be made over the heads of people who’ve put their trust in us. Rather, it is to ask: If the abuse is an open secret, what is it that’s stopping people from speaking up, from addressing the issue?

TZK: Perhaps their own professional situation, often experienced as precarious, holds back even those who see themselves as feminists from speaking out about sexualized violence in general. Sabeth, you teach at an art school yourself: As a professor, have you seen any structural systems being put in place or the development of a “culture of looking closer”?

SB: There’s actually been a working group for equality with a support point for grievances, complaints, and problems at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna since the early ’90s. It offers solidarity and is effective as a body. It’s also committed to working with discretion. Its recommendations don’t always manage to claw their way through the administrative jungle, which reminds us time and again of its frustrating powerlessness. There’s also the fact that what Christina spoke about – personal intervention by work colleagues – is incredibly difficult, especially when those colleagues have to work on a collaborative basis or have good relationships with those accused of abuse on other levels. If maybe you as a teacher, especially an older teacher, notice that work colleagues are lusting after students, alluding to that fact will often lead to outraged reactions per the motto “they’re fully grown adults! How can you take away their autonomy like that?” These are often incredibly delicate situations that need the kind of safe space provided by the working group just mentioned. That makes it possible to speak about incidents – often enough only semi-perceived – and to reflect on them without the threat of immediately being punished for maternalistic/paternalistic behavior: safe spaces for people who’ve been affected by abusive behavior, but also for the ones sticking their heads above the parapet to call attention to abuses of power. Because how do you even formulate your discomfort about all this without prematurely sticking the knife into someone and ending up being seen as disloyal?

Katrina Daschner, „Collective Energy (Basic Position)”, 2021

CC: I also think it’s imperative that male staff finally get involved. Why is it they all think it’s nothing to do with them so long as they’re not committing abuse themselves? Is it because really every one of these men is afraid that something about him might be exposed? If that’s the worry, the problem would be relatively easy to solve. Or is it lack of interest? Do they have more important things to do than worry about the safety and well-being of female-read and trans people? Why isn’t it in their own interests to create and secure violence-free spaces? It’s important for educational institutions to constantly address with their students the issue of abuse of power and sexualized violence, even during the introductory stages of students’ studies. The position should be, “Sexualized violence happens everywhere, including here, and it’s not okay. We want to combat it together, and we need everyone to be on board.” Spaces need to be opened up, and sufferers who speak up need to be given moral support – they need to be told that they’re not alone and that this isn’t just their problem, it’s collective. No defensiveness: it’s about acting in solidarity, being grateful to those who speak up, and making sure that change happens.

TZK: Another good reason, we feel, for paying particular attention to art schools is because the central structures and role models of the art field are established there. What are in Germany still called Meisterklassen [special “master class” postgraduate courses offered to select students by leading art professors, with the word Meister appearing in the grammatically male form – TN] are paradigms of this: students’ success is heavily dependent on their relationships with the professors.

SB: This is why – not only as a result of the Bologna reforms – many art schools are promoting the idea of students not just staying in one professor’s class throughout their studies, but of switching professors from time to time. And it’s happening now, too. But there’s always been a rejection of decentralized art teaching. Teachers and students are attached to the family-like structures of these groups – and this is true of the theory department too, like with doctoral supervision. Education at an art school – so one of the arguments goes – doesn’t function primarily through course-based input of teaching content, but through personal exchange and at-times uncomfortable confrontation. Students have to “grate” against authority ...

TZK: Art professors usually come directly from the art world. They have pretty much no expertise in working responsibly with young people: they actually come from environments where the boundaries between profession and party don’t seem to exist.

SB: When we put out job listings, we make sure that they say “didactics” [as the art and science of teaching – TN], not “pedagogy” [as the all-round education or nurture of a child/person – TN]. In 2017 Coco Fusco described the still-widespread resistance to a culture of pedagogy that continues, somewhat irresponsibly, to be seen as the natural enemy of Bohemianism. [11] Pedagogy just doesn’t sound sexy. It sounds moralizing. Still, I don’t want to conceal the fact that I have a bit of a thing for unacademic or de-academicized formats, too.

TZK: Might it be possible to come up with a structural counter to this – by making teaching staff attend compulsory training courses, for example?

SB: Definitely. And it’s coming. Among my colleagues, pretty much everyone recognizes the need for this kind of awareness-building – discrimination in all its manifold forms is virtually constitutive of art school, after all. We have to realize that only a maximum of around five percent of graduates end up finding a place in the so-called art market and that, while the Abitur [German high-school diploma generally required for university studies – TN] isn’t an entry requirement, hardly anyone from educationally disadvantaged backgrounds makes it into art school. Not to mention the disadvantages faced by many applicants read as migrants or from so-called third [non-EU] countries. Queer, non-binary, trans, and disabled students are bringing structural and day-to-day discrimination to our attention. Finally: What does the principle of selection do to the subjectivity of students if professors are signaling, “I chose you! And I will support you”?

Adina Pintilie, „Touch Me Not”, 2018, film still

CC: If everyone in the art schools sees the need for structurally embedded services, then there’s reason to be optimistic. Would you say that the backlash suggested by Kaiser isn’t really discernable in this context?

SB: No, it’s happening, even at the Academy of Fine Arts [in Vienna]. The supposed political correctness at our art school also gets met with defensive and reactionary responses, of course. Artists and theorists ultimately want to be recognized as non-conformist – and while the art market likes to posit itself as “woke,” the systematically “non-correct” or “anti-correct” ones are often the most successful because, in keeping with what was said at the start, they are seen as the freer, more artistically interesting spirits. Making those kinds of claims – of being distinct – still pays off. In my experience, the backlash is the serial primal scene of the art school.

CC: We could also look at it in a totally different way and say, “art school is, from a legal perspective, a dangerous place.” Schools are responsible for ensuring that specific dangers don’t become realities. They have to ensure that the roof doesn’t collapse in the middle of class, and likewise that no sexual assaults happen. This isn’t just something that individuals are responsible for – it’s also the responsibility of the institution, which has to recognize these responsibilities and create structures to minimize the dangers. In just the same way that the structural soundness of the roof has to be checked, people have to be informed of what is and is not allowed. Meaningful rules have to be established and enforced, and there have to be consequences – even letting people go, if necessary. Otherwise the art school could be sued when assaults happen – because, ultimately, it failed to ensure the health and safety of all its members. Ultimately, there is a lack of consequences, and in my view these have to be faced not just by individual perpetrators but also by the institutions in which perpetrators are active. Making things public is key to making sure that there are consequences. How can everyone learn to call out misconduct, given that time and again – as Sophie Jung suggests in the König case – people in the know say nothing? I wouldn’t say that this makes them guilty – as it’s the perpetrators themselves and the structures that fail to prevent assault that bear the guilt. So those structures have to be made liable. Consequences for them – whether in the form of damage claims or whatever else – have to be demanded. They have to be public denouncements. The Hamburg Higher Regional Court issued a decision in December that really points the way forward. [12] On the essential principle of reporting on alleged offences, it said that with regard to prominent public figures, reporting is permitted if a larger number of victims are affected, if the reporting is of a serious nature, and if the reporting is not merely concerned with denouncement and is genuinely in the public interest. As important as this decision is, it’s also a good example of a particular problem: the discussion gets bogged down in negotiating the limits of reporting, which distracts from the real problem – sexualized violence. Journalists and victims often end up being discredited, even held liable.

ID: It’s a paradox: as soon as it was finally decided that it’s legally permissible to speak publicly about the König case, little more was said about it. The conversation seemed to be over. There was a lot of noise, then that was it already. Any chance of taking this affair as an opportunity to finally speak publicly and more broadly about structural sexualized violence in the art world was wasted. It was as if Johann König were just one isolated case. Silence in this context is extraordinarily eloquent. It’s probably on social media that the König debate was conducted most comprehensively …

TZK: Soup du Jour, an anonymous feminist collective, ran a Facebook campaign that was prominently supported by Candice Breitz and extremely public in its efforts to show solidarity with those affected in the König case. Let’s just say the medium they chose didn’t exactly contribute to a nuanced debate. How did you feel about their repeated statements?

SB: More than anything, I was impressed by the careful way in which Soup du Jour initiated and conducted the campaign. But I gradually began to feel ambivalences, because the campaign cannot, of course, be divorced from the market logics – the keyword here being attention economy – in which Johann König’s gallery is obviously an upper-tier player. As are some of the artists he represents. In the art world – which operates somewhere in between the traditional and neoliberal markets, and increasingly on social media – I can’t ignore the increasing pervasion of what theater scholar Kai van Eikels has called collaboration-competition. Feminist collaboration can be about competition and contest, too. The call-outs directed at Monica Bonvicini and other artists honestly gave me a headache.

ID: Soup du Jour’s focus on Bonvicini was, to my understanding, mostly about her presenting herself in the international art world as a feminist artist – something she earns capital from. The fact that instead of leaving the gallery she just put her working relationship with it “on pause” led Soup du Jour to believe she was trying to keep all doors open – both to the market and to feminists. So for their part, they gave her a clear no. [13] But the extent to which it’s useful to put someone under pressure publicly is another question.

SB: There’s also the question of the motivations of the female artists who pulled the ripcord extremely quickly following the Die Zeit accusations and the first calls for solidarity. Is that something they did out of political conviction or moral indignation? Or because they had offers or were already represented by other powerful galleries? Was it about sending signals to the “woke” art world of the US? There are some for whom quitting would result in losing their means of earning a living. So, from the outside looking in, how am I meant to assess their decisions? How am I meant to judge that? I’m extremely ambivalent here, if I’m being honest, even if I of course want to see everyone – not just female artists – positioning themselves in solidarity against sexual abuse of power. It’s also striking that no one in the art scene openly expressed solidarity with König – or maybe it’s just that I didn’t notice. Various interpretations are possible here, too: this non-expression of solidarity could be understood as the manifestation of a culture of silence, but also as relief at seeing the weakening of a professional competitor – one who has been so successful for such a long time. It’s also known that König isn’t the only one who has allegedly committed assaults – so who would want to make themselves conspicuous here by speaking out loud? This once again forces the question of how to deal structurally with problems and conflicts, not just with individual cases.

ID: Alongside a more nuanced debate, I feel there’s a need for more transparency and that over the long term, these kinds of conflicts have to be made political at a fundamental level.

CC: I’m often surprised, actually, about how things work in this country, about how so few victims get furious. Why does the problem keep getting swept back under the rug? Why doesn’t it become a genuinely public discussion? Within the current structures, the issue only ever flairs up for a second. Then things go right back to how they were.

SB: How can anger be articulated in a way that, instead of burning out in the short-term rhetoric of indignation, generates tools that help us to critique power, tools that victims of sexual abuse can use without fear of betrayal, shame, or failure, under conditions of solidarity and anti-discrimination, within the framework of the groups and institutions that are there to protect them? That’s what the Soup du Jour campaign stood for first and foremost.

Translation: Matthew James Scown

Other recent contributions on the topic: “When Silence Speaks”: Soup du Jour on feminist solidarity and taking action against structural disparities.

Sabeth Buchmann is a professor of modern and postmodern art history at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna and coeditor of PoLYpeN, a series on art criticism and political theory (b_books, Berlin). Her most recent publications are: Kunst als Infrastruktur (forthcoming) and Broken Relations: Infrastructure, Aesthetic, and Critique (coeditor, 2022).

Christina Clemm is a lawyer specializing in family and criminal law. She has represented victims of gender-based, anti- LGBTIQ, racist, right-wing, and anti-Semitic violence for many years. Her book AktenEinsicht: Geschichten von Frauen und Gewalt (Inspection of the record: Stories of women and violence) appeared in 2020. Her book Gegen Frauenhass (Against hatred of women) will be published in September 2023.

Iris Dressler is joint director of the Württembergischer Kunstverein (WKV) Stuttgart, alongside Hans D. Christ. In 2019, she and Christ were artistic directors of Bergen Assembly. A current exhibition series is dedicated to artists dealing with intersectional feminist perspectives; it includes Carrie Mae Weems (2022), Trinh T. Minh-ha (2022), Delphine Seyrig (2023, curated by Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez and Giovanna Zapperi), and Adina Pintilie (2023, curated by Viktor Neumann and Cosmin Costinaș). Her most recent publication (coedited with Hans D. Christ) is 50 Jahre nach 50 Jahre Bauhaus (50 years after 50 years of Bauhaus, 2022).

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of Verena Dengler, photo © Thomas Duncan Gallery/Ruben Diaz; 2. © Andrea Fraser; 5. Courtesy of Monika Treut, distribution Edition Salzgeber, photo Hyena Films; 4. © Zanele Muholi, courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson, New York; 5. Courtesy of Petra Bauer and SCOT-PEP, production Collective/Frances Stacey; 6. Courtesy of Katrina Daschner; 7. © Adina Pintilie

Notes

| [1] | Susanne Kaiser, Backlash: Die Neue Gewalt gegen Frauen (Munich: Tropen, 2023), 51. |

| [2] | “The 100 Most Influential People in the Artworld in 2018,” ArtReview, November 8, 2018. |

| [3] | See Irina Aristarkhova, “#MeToo in the Art World: Genius Should Not Excuse Sexual Harassment,” The Conversation, May 3, 2018; “Is the Art World’s #MeToo Reckoning Coming?,” Art Critique, March 10, 2020. |

| [4] | See, for example, Sascia Bailer, “Wie es um Geschlechtergerechtigkeit in der Kunst steht,” Monopol, March 8, 2023; Sophie Jung, “Sexualisierte Gewalt im Kunstbetrieb: Hierarchien im Schönen,” Tageszeitung, Sept 11, 2022. |

| [5] | Jerry Saltz remarked in Artnet that Fraser is “in excellent shape for a 39 year old” and “gives an attentive blow job.” Quoted in: “Have We Finally Caught Up with Andrea Fraser?,” New York Times Style Magazine. Andrea Fraser on her work: “Andrea Fraser,” Brooklyn Rail, October 2004. |

| [6] | See You Are Another Me: A Cathedral of the Body, https://www.cathedralofthebody.com |

| [7] | See The Beast and the Sovereign / Die Bestie und der Souverän, exh. cat., ed. Hans D. Christ, Iris Dressler, Paul B. Preciado, Valentín Roma (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2018). |

| [8] | Luisa Hommerich, Anne Kunze, and Carolin Würfel, “Ich habe ihn angeschrien und beschimpft, damit er weggeht,” Die Zeit, August 31, 2022. The online version of the text differs from the original print version; König took legal action against Die Zeit, forcing it to change a number of passages (see footnote 12). |

| [9] | Sophie Jung, “Sexualisierte Gewalt.” |

| [10] | “Initiative FAIRSTAGE” press release by the Senate Department for Culture und Europe, Berlin, May 12, 2021, (in German). |

| [11] | Coco Fusco, “How the Art World, and Art Schools, Are Ripe for Sexual Abuse,” Hyperallergic, Nov 14, 2017. |

| [12] | Editor’s note: The Hamburg Higher Regional Court’s decision is available online. |

| [13] | “König Galerie und Künstlerin Bonvicini gehen getrennte Wege,” Monopol, November 11, 2022. For a commentary on the feminist conflict, see Gürsoy Doğtaş, “MeToo: ‘I won’t shut up,’” Freitag, issue 47/2022. |