SEND IN THE CLOWNS Sasha Rossman on Amy Sillman at the Kunstmuseum Bern

“Amy Sillman: Oh, Clock!,” Kunstmuseum Bern, 2024

Switzerland is known for its mountains, chocolate, money (laundering), and clocks. Amy Sillman takes up one of these associations in the title of her current exhibition “Oh, Clock!” at the Kunstmuseum Bern, which will travel to the Ludwig Forum Aachen in spring. Almost in spite of the amusing Swiss reference, the deceptively exuberant phrase poses several questions to the visitor: Oh, Clock. O clock. O’clock! Does the tone go up or down at the end of the expression? Is it a wistful “Oh clock” (as in “Oh dear”), or an upbeat “Oh! Clock!” (as the exclamation point might indicate)? Since a clock’s face goes round-and-round, it could likely be both: sometimes up, sometimes down; sometimes bottoming out, sometimes on top.

The exhibition’s title, moreover, takes a specific rhetorical form: the apostrophe. Apostrophe is the vocative “O” that can be heard in “Oh, Clock”; it is a poetic device that interpolates the listener, or reader (or in Sillman’s case, viewer) in the present. The apostrophe is so self-conscious that it deliberately draws attention away from the pretention of narrative and speaks to us in a form of direct address. In doing so, the apostrophic does not point to a specific word, as Jonathan Culler has observed, but to the very “circuit or situation of communication itself.” [1] Apostrophe is a kind of punctuation (but not to be confused with the eponymous punctuation mark); it places us in a moment of suspension, where we oscillate between the descriptive temporality of narration and the instant in which we find that narrative to be self-consciously suspended in the now – like the moment in which a clown looks plaintively, or with an exaggerated smile, at an audience before performing a trick or routine. An apostrophe is, to use W. H. Auden’s words, “A way of happening, a mouth.” [2] O clock!

“Amy Sillman: Oh, Clock!,” Kunstmuseum Bern, 2024

For Sillman, this form of address offers a rich territory to mine: Her work is filled with varied explorations of temporality and its manifestation in painting particularly, but also in drawing, printmaking, and animation, all media that find a place in the Bern exhibition, which includes a selection of works made over the past 15 years. Recent writing by the artist, as well as by commentators on her work, has addressed the temporal dimensions of Sillman’s practice. [3] She engages deeply in art history, plumbing its depths to gestate and reanimate elements of reputedly outmoded painterly expression. Parallel to this, temporality finds expression in her paintings through surfaces that show off the time it took to paint them (or scrape them, or rub them, or delete them). Moreover, Sillman also likes to work in series, either in deceptively quick gestural drawings made over extended periods of time, or in prints with many layers, animations, or even digital renderings of different stages of a painting as it emerged. In this manner, the pronounced nowness of Sillman’s works – their apostrophic “O” – rubs up against her obvious interest in the time it takes to make them. This moment of suspension manifests itself in various ways, including vibrant contrasts in color, self-conscious mark-making, and juxtapositions of sign systems that produce humorous, and sometimes awkward, friction-filled physical viewing experiences. The slapstick nature of this insistent present-ness threatens to collapse linear time even as the paintings (and drawings and prints and animations) lay the durational process of their making bare. All of these aspects of the artist’s practice are on display in Bern.

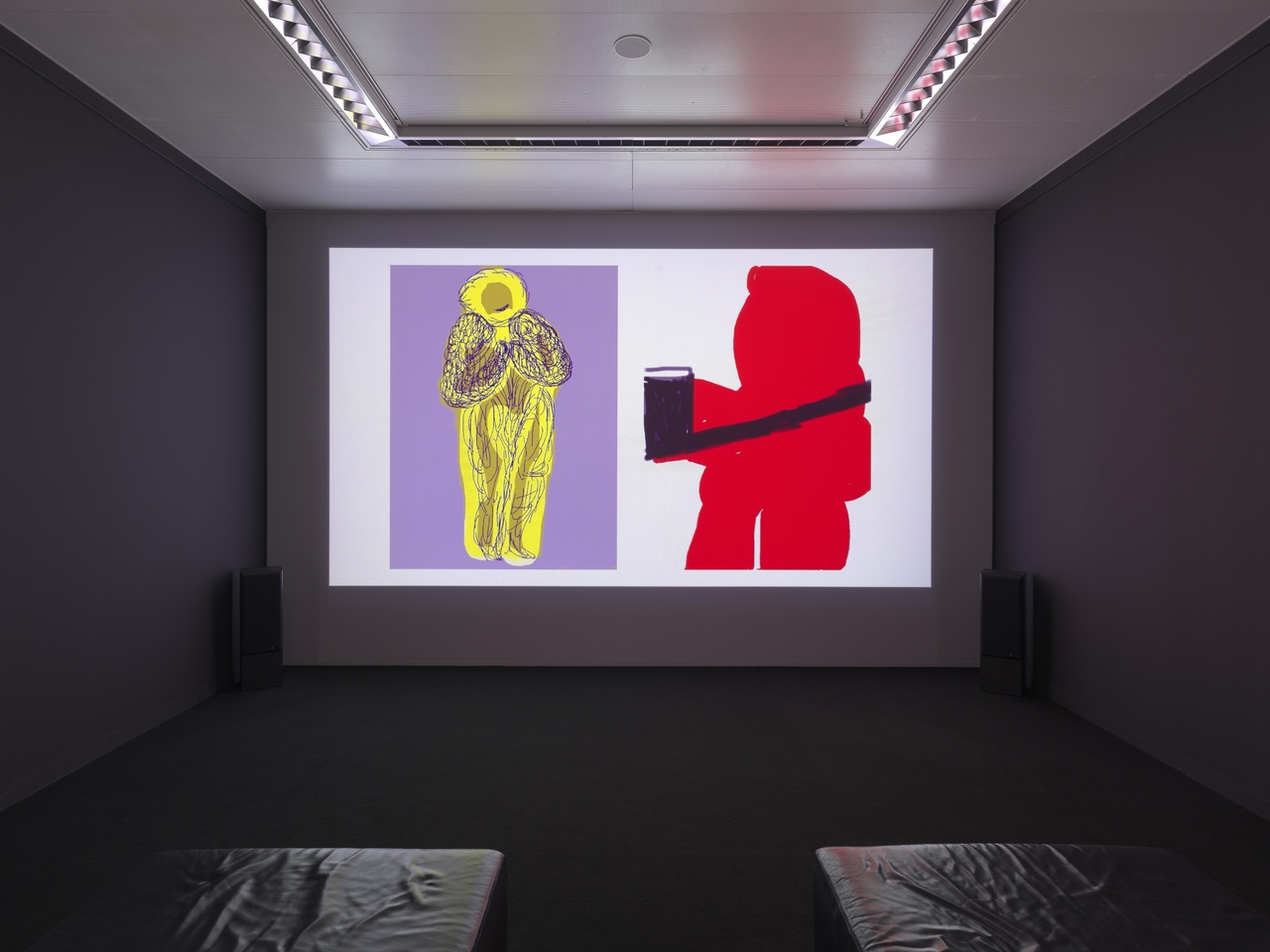

Walking into the show, to the left, one encounters two of Sillman’s animations with a whirring, ticking soundtrack by Marina Rosenfeld. As their titles indicate, Spring: Abstraction as ruin (2024) and Summer: Abstraction as apprehension (2024) bear some relation to the passing of time. In spite of the formal and narrative differences in both short sequences, elements of figuration and abstraction collide, as do words and utterances with gestures. A mouth opens as a line of paint, then becomes a text, but also a kind of gurgle or gagging (think Auden). Speech acts become gestural marks, which both embody and obfuscate meaning. Figures are engulfed by what appear to be holes, or pipes, as well as lines and shapes. The clock winds around, like the rotation of seasons, moving forward, but also erasing what preceded.

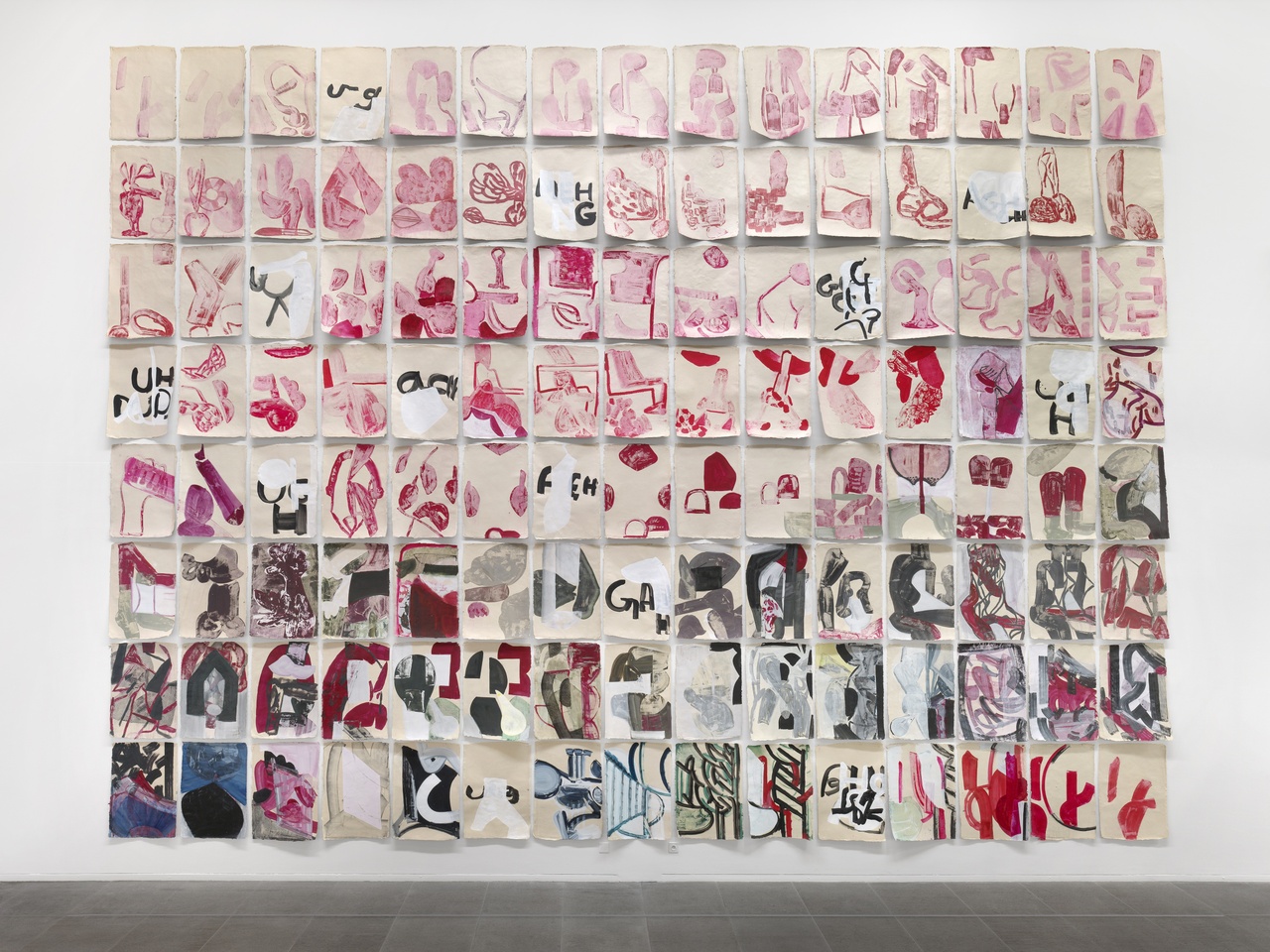

Amy Sillman, “103 UGH for 2023 (Words)” and “195 UGH for 2023 (Torsos),” 2023–24

To the right, on a soaring wall of the double-storied building, hundreds of individual sheets of paper climb up toward the museum’s roof. As in the animations, the series 103 UGH for 2023 (Words) and 195 UGH for 2023 (Torsos) (both 2023–24) are scrawled with gestures as well as utterances. Onomatopoeic sounds tumble across the sheets: “ohg” and “uqh” in layers of gray, pink, red, black, and white. The act of making them seems like a daily exercise in which gestures layer into words, erasing the fixity of the sounds’ already ambiguous meanings. As a consequence, a both verbal and pictorial signage appears to take form and destroy the underlying language. Here, as in the rhetorical apostrophe, narrative is suspended in spite of the gridded rows of drawings; the information the group conveys does not progress from left to right, or top to bottom, as in a telos-driven text: at every instance the individual drawings, as well as the ensemble, seem instead to cry out “O” to us in the present; a moment that we know has passed is nonetheless figured as a kind of viscerally suspended ugh.

Following these painterly pronouncements up the museum’s cantilevered, open staircase, one also comes into contact with colorful paint, which seems to be escaping from the exhibition’s second floor. The two-story structure is key here to the artist’s play with temporality and the circling of o’clocks. On the bottom floor are works by Sillman. On the top floor, Sillman has curated a selection of artworks from the museum’s collection, which she has layered on top of her own gestural, colorful wall paintings. These ensembles, which are unlabeled like the works by Sillman downstairs, form associative constellations. An olive-green stripe on the wall brings together slithery surrealist paintings by Kurt Seligmann, Meret Oppenheim, and Paul Klee that feature corporeal shapes peppered with orifices and a plaster by Auguste de Niederhäusern featuring a figure, mouth agape, howling against the avalanche of plaster. The conjoining features between these works are color, roiling shapes, gaping holes, mottled and rough surfaces: Niederhäusern’s crusty Avalanche (1890–91) spills right into an abstract Sigmar Polke black-and-white photograph, and then into more Sillman wall gestures, and finally into a heavily impastoed small colorful croûte of a painting by Pia Fries, building a non-linear chain of formal associations and nods to embodied states like pressure, collapse, convulsion, or tumescence. In another room, a Fernand Léger composition peers across the wall at a Monika Baer stitched painting of a breast spurting milk. The rounded forms in Léger suddenly appear uncharacteristically funny, and remarkably boob-like. “Ohg” or “Gikmfk” seem like more appropriate descriptors in this display than any kind of plotted art historical narrative. Instead of timelines, Sillman has displayed objects from numerous historical periods that share an interest not only in shape and color, but also certain specific types of forms, particularly holes, gaps, and reversals of top and bottom positions.

“Amy Sillman: Oh, Clock!,” Kunstmuseum Bern, 2024

This interest in embodied “vers-ness” – a flipping of sexual roles and binary positions between dom–sub, top–bottom, up–down – courses throughout the show alongside the interest in temporality. On the “top” floor, Sillman has carefully orchestrated both her colored murals and the works on view in ways that play on formal reversals. A Franz West sculptural “white room” is matched by a “black box” in which Leidy Churchman’s video Painting Treatments (2010) unfolds. In the latter, the viewer encounters bodies and body parts being slathered in skeins and pours of viscous colorful paint, which flows over them and onto the ground. This corporeal painting, in turn, seems to squirt from the top floor into the exhibition’s “bottom.” On the one hand, the visitor finds certain elements of the second floor echoed below it: lemon-like shapes that Sillman painted on the wall beside the Léger appear in the painting She/They (2021) downstairs at the same spot in the floor plan as the lemons above. Here, however, they seem to have been associatively and literally ingested by a semi-figuration. A kind of rumbling drum pedal below the fruits seems – as in a Rube Goldberg machine – to be boinging them, and threatening to eject them into an orange tubular shape – or is it a tinny tuba with its musical “oooh”? Flip-flopping finds expression, on the other hand, in Untitled (Frieze for Venice) Large 29 (2021), for instance. Here, Sillman pairs horizontal frieze-like bands of smaller images above individual vertical silkscreens that are simply nailed onto the wall below. The landscape format here tops the portrait format in a reversal of traditional genre hierarchies. In the lower register of the prints, elements from the upper frieze drop in, where the legibility of their already mercurial meanings is further confused by Sillman’s cavalier play with the silkscreen medium. In the prints, Sillman layers gesture and rasterized elements unique to the silkscreen in ways that confound any attempt to figure out how they were made. Everything that seems on top could well be on the bottom, and what is underneath also simultaneously appears to be on the surface. This space of oscillation seems to be what makes Sillman’s clocks tick.

Vers-ness and time conflate in this show in a way that produces a form of painting (and drawing, and printing) that asserts itself as a vibrating friction imbued with corporeal, semantic, and temporal dimensions. Apostrophe, Culler reminds us, “may raise or be used to raise questions about who or what is the speaker and who or what the addressee” just as Sillman’s works like to capsize differences of top and bottom, as well as words and shape. In numerous works in the show, the differences between word, gesture, and material form become conflated, disrupting clear distinctions between them. This is the case in Sillman’s animations and drawings clearly featuring text, but also in those that do not even include writing, such as The Banana Tree (2023). Here, black gestural marks are layered upon colors including a banana yellow. The color connotes “banana” in one manner, but so do the black gestures, with their clusters of curving banana-sized shapes. Words and figures of thought morph into shapes and colors in a manner that eschews categories and hierarchies, preferring instead to flip-flop. It’s a stretchy, almost elastic energy, and one that snaps with humor.

Leidy Churchman, “Painting Treatments,” 2010

Like Sillman’s works, apostrophes are, according to Culler, somewhat “embarrassing: embarrassing both to the author and his reader.” [4] There is something so self-consciously artificial, nearly clownish about them. How can we take an artist seriously who calls out to us in such an earnest fashion, which simultaneously connotes a real belief in the power of the work of art with such deliberate artifice? “Send in the Clowns,” to quote the famous showtune. Wait! They are already here – in the paintings Clown (2023–24) and Clownette (2024), for example, to name just the two most direct references.

These paintings and, indeed, all of the works in the show, directly position the artist – but also painting itself – as a clown, a comic entertainer who speaks in a language comprised of codified movements, gestures, and costumes rather than a narrative syntax. Clowns are not only scary, but also often embarrassing for the manner in which they so frankly appeal to their viewers’ emotions. Sillman’s clowns, however, occlude any clearly legible readings, or even figures. In Clown, a scumbled, or perhaps scraped, rectangle of white on black, defined by blue and gray lines, may be a pair of clown pants viewed from behind; there may be a clumpy set of fingers in the painting’s center, and vibrating orange and blue dots on a darker teal are somewhat reminiscent of the splotches of make-up on a clown’s face. But rather than directly acting out emotional meaning, as would a human clown, the work tries to communicate through an interplay of looping lines and layers of complementary colors that rub up against each other and chromatically vibrate. Pared down to these base signs of color, form, shape, and line, these clowns are speechless but nonetheless expressive. They call the viewer to join in squirming against the tension of happening and becoming, of uttering and obfuscating.

Amy Sillman, “Untitled (Frieze for Venice),” 2021

How, then, and in which ways does Sillman stake a claim for a clownish painting in the now? She does so by manifesting temporal duration and addressing the viewing experience in the present through the forthright embrace of painting’s visual and physical qualities. The latter produce a kind of thick and vibrating mode of present time, which may or may not be awkward, or funny in its emphatic corporeality. “Well, I hope making art is like releasing a vibration into the atmosphere,” the artist declares in an interview included in the show’s catalogue. [5] By vibration, Sillman seems to mean a friction experienced across multiple registers, one of which is also the rebelling against fixed positions: the artist’s exploration of “vers-ness” as a painterly strategy alongside her interest in excavating the physical traces of time’s passage. Sillman sends time, and painting, into a web of deliberately awkward tangles, which vibrate directly to Uranus.

One of the defining developments in time-keeping technology is a device known as the “escapement.” The escapement funnels energy lost in the friction of the clock’s mechanism back into the ticking of the seconds with renewed force. It is the instrument that perpetuates the clock’s tick-tock by linking and fixing the clock’s wheels to the energy of a pendulum. This vibrating escapement offers, in Sillman’s work, no escape, but rather a clamoring apostrophe, an “O” which brings us back to the uncomfortableness of the present. A present in which we struggle against the imposition of having to take a defined position, and one in which we are squeezed from all sides by constraints that threaten to smoosh our bodies and psyches. Through the viscous and messy media of paint, print, and animation, however, this present also becomes, for Sillman’s viewers, a source of pressured pleasure. There is no escape. There is only the energized confinement of escapement. Sillman’s show asks us to really feel this rub and to find stimulation in its grating, sometimes embarrassing, messiness. Oh, clock!

“Amy Sillman: Oh, Clock!,” Kunstmuseum Bern, September 20, 2024–February 2, 2025 (and Ludwig Forum Aachen, March 22, 2025–August 31, 2025).

Sasha Rossman is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bern’s Institute for Art History.

Image credit: Courtesy of Kunstmuseum Bern, photos © Annik Wetter

Notes

| [1] | Jonathan Culler, “Apostrophe,” Diacritics 7, no. 4 (Winter 1977): 59–69, at 59. |

| [2] | Culler, “Apostrophe,” 62. |

| [3] | See, e.g., Amy Sillman, “Ab-Ex and Disco Balls: In Defense of Abstract Expressionism II,” Artforum 49, no. 10 (Summer 2021), and also the exhibition catalogue, Amy Sillman, Kathleen Bühler, and Eva Birkenstock, eds. Amy Sillman: Oh Clock! (Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, 2024). |

| [4] | Culler, “Apostrophe,” 59. |

| [5] | Amy Sillman and Michelle Kuo, “Ham Radio: A Conversation between Amy Sillman and Michelle Kuo” in Sillman, Bühler, and Birkenstock, Amy Sillman: Oh Clock!, 167. |