ANNETTE WEISSER TO BRUCE HAINLEY Berlin, June 28, 2025

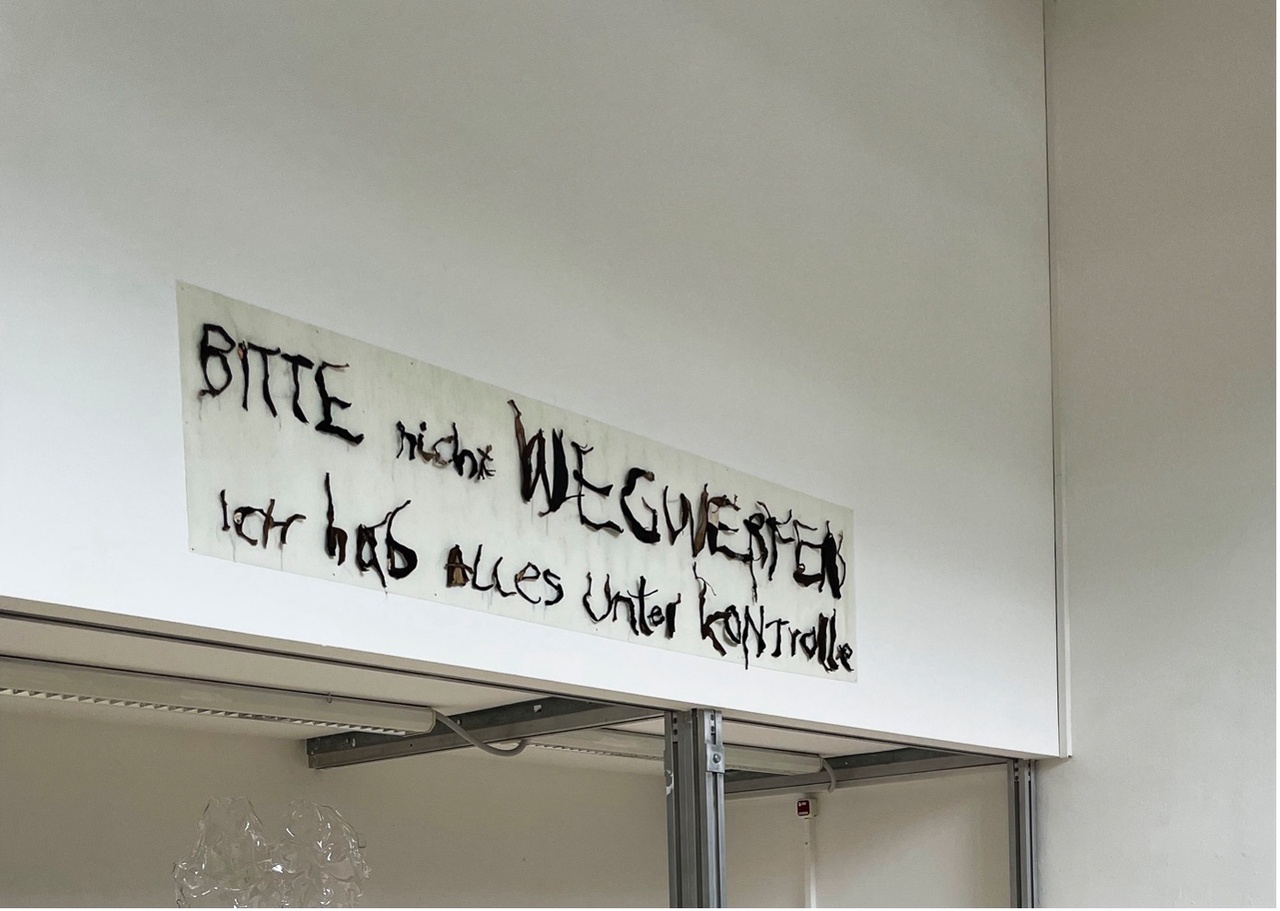

Waleria Sadkow, “BITTE NICHT WEGWERFEN ICH HAB ALLES UNTER KONTROLLE”, 2025

In times when doom news comes thick and fast, diplomacy is reaching its limits, transatlantic relations are crumbling, and interrelated crises seem to call for heuristic abbreviation, we’ve come to miss some of the virtues fostered by the friendly, long-form communication between pen pals. That’s why we have asked Annette Weisser in Berlin and Bruce Hainley in Houston to exchange views on current political developments and sociocultural shifts, as well as how these impact the art world, in a decelerated rhythm of correspondence. Their letters will be published alternately over the coming months, as a means of jointly exploring the present and of maintaining close connections across long distances. The first two letters were both written during the academic summer break. Annette Weisser starts us off with a report from Berlin, where she reflects on the deeper drives of traffic offenders, on Ghislaine Leung’s practice, on shifting concepts of critique, and on a new book by Sophia Eisenhut, among other things.

Dear Bruce,

I’m truly looking forward to this exchange and I wonder how we should go about this generous invitation. Having gladly accepted it, getting started turned out to be rather tricky. (Also, I very recently stopped – not saying quit! – smoking, which is not exactly helping with the thinking and the writing.) Since the time we both taught at ArtCenter, Pasadena, my son and I moved back to Berlin in 2019, and you moved on to Houston a few years later. That shared space of meals and drinks, laughter and debate, feels like part of a very distant past.

I remember that, in 2016, you were the only person in my circle of friends both in LA and in Berlin who predicted the outcome of the November election correctly. I guess you had a more realistic perspective on where the US was headed than most of us did, in our urban bubbles. (I’m catching up now by watching Yellowstone and its many spin-offs. It took me several failed attempts because I really can’t stand Kevin Costner – like, the obscene manner in which he moves his tongue around the mouth?) What “we” – that “we” which tends to get thrown around rather carelessly – thought back then was that this outburst of infamy was an outlier, a historical irregularity that will autocorrect itself after four years, which it did – only to return full force. I recently thought about the Contemporary Masculinity seminar that we conceived and co-taught sometime pre-2016: We looked at everything from internet porn to Rainer Werner Fassbinder, read Herman Melville and Gilles Deleuze. Perhaps you were less optimistic than I, who couldn’t foresee the misogynistic, homophobic backlash that is underway now in the US and in many European countries, including my own.

Slowly, an image of the future is emerging. Perhaps it’s a minor thing in the bigger picture, but in Berlin, drivers are increasingly jumping red lights. Not dark yellow, not orange, but deep red. Apparently, they just count on everyone else stopping in their tracks to let them pass. (Needless to say, these reckless drivers tend to be male.) The reason I bring it up is that it seems to correspond with the cancellations of social contracts that are happening on so many levels right now. When I’m in this situation, as another driver, I’m left with a peculiar mix of contradicting emotions: indignation, for sure; impotence, because I don’t have a choice but to condone this behavior; but also envy. I want to be that reckless driver, I want to be in possession of that – I guess the correct word is virility, that would render me immune to the petty needs and concerns of other people. I want to know what that feels like. Which then triggers another emotion: shame, for harboring these dark desires. And after the other driver is long gone, I sit in my little electric car, foot still on the brake pedal, confused and angry.

I guess all this pent-up anger has to go somewhere. On a recent Sunday morning I woke up to this fantasy – or was it a dream? – around a very rich bald guy who just got married in Venice: His whole wedding party was under attack, shot at with stinky red paint by activists posing as altar boys at the ceremony. The moment they all swung around simultaneously and grabbed their humongous water guns from underneath their gowns; the shocked, surgically enhanced visages of the guests in attendance – that image made me happy all day.

It’s a strange time to be given carte blanche for a writing assignment. Never in my adult life have I been less sure of what I can say with certainty, less convinced that the way I look at the world is … defendable? As for many others, the erosion of my lifelong belief that things are basically moving in the right direction began with the 2016 US election, seamlessly followed by the Covid-19 pandemic. Ever since, personal difficulties – a recent death in my support network, job insecurity, a storm ravaging the garden – take on darker undertones, seem more insurmountable than they would have been nine years ago. Also, I’m nine years older. I can’t tell apart the factors that make up this bottomless exhaustion. I often stare out of the window until something – the doorbell announcing the delivery person, a sparrow at the feeder – snaps me out of this near-catatonic state. I want to withdraw from the necessity of creating something. I refuse to have opinions. For the first time in my life, I want to just sit and listen and be in the world and I wish this would be enough. (Of course, I’m aware of the irony of articulating such sentiment and getting paid for it, even if only modestly.)

Looking at current exhibitions and debates, it seems that I’m not the only one who feels this way. Withdrawal, refusal, delay – these concepts pop up a lot. Recently, at a panel discussion at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein in the context of Ghislaine Leung’s show “Reproductions,” I typed into my phone Delay opens up a space for affect. David Joselit said that, on this panel, in regard to the current political situation in the US. I understood that what he meant was: Let’s not play into their media strategy of “flooding the zone with shit.” Instead of jumping at every outrageous sound bite, let’s sit with it until an internal response arises. It’s a form of mental self-care, but moreover, it’s a means of staying in control, which is the precondition of taking action. (As a professor at Harvard University, which has become a highly unlikely place of résistance, he spoke from experience.)

I know that you have collaborated with Leung on numerous occasions, but for me it was the first time I saw her work in person. In the front room, remnants of the previous show were left untouched after the deinstall – the walls still partly painted black, drillholes visible, the windows uncleaned, electric wiring spilling from a hole in the drywall quite dramatically. The back room was completely empty except for a soberly designed cost schedule on one of the walls; Leung has made transparent the entire budget that went into the production of this show. My initial reaction was: Oh, okay, the next generation is reinventing institutional critique. Nevertheless, the next morning, I went online to read up on her. Surprised and therefore excited, I learned that in her work the site of critique isn’t so much the institution’s embeddedness (hidden or obvious) in political and economic power. Rather, it’s the liminal space where the fragile existence of the artist chafes against the economic and logistic demands of the art world. Being a mother, Leung takes up the question that is still (still!) relevant today for most female artists with children – How much of my time and energy am I willing to sacrifice to have a career? – and rephrases it: How can I design a practice that sustains my career without having to make those sacrifices?

The exchange with curators and museum staff that is at the heart of this practice (to a large extent, Leung trusts the curators with implementing her scores) must resemble some kind of dance that leaves the curators utterly enchanted. That affective quality of her work, which is perhaps most obvious in her writing, touched me quite unexpectedly.

There’s a big difference between activating one’s vulnerabilities for a critical inquiry of labor conditions in the art world and insisting on those vulnerabilities in order to avoid critical engagement with the world at large. Looking at art students now in their early twenties, I’m often puzzled by their shift away from the concept of critique I grew into during my so-called formative years in the 1990s. From my perspective, it sometimes looks like intellectual laziness, with a whiff of narcissism and entitlement. I assume this disengagement also has to do with the pandemic; this cohort is indelibly stamped by the experience that the well-being of children and young adults is deemed less important than, say, the production of cars. They have no illusions about what kind of world they’re growing into, knowing that those in power don’t give a shit about them and their future. (Case in point: The latest cuts in education and environmental protection.) It doesn’t make sense to mount a critique when nobody is listening. Yet I am not entirely sure if the articulation of vulnerability already counts as political. Perhaps it would be worthwhile to ask what could replace critique as a set of tools designed to dismantle the master’s house – because the house is still standing, grander than ever, even if half a generation of smart young people refrains from setting foot inside to see where new tools could be applied.

Now I seem to be the pessimistic one – perhaps overly so. Hilarious, touching, and provocative art often does originate from exploring one’s own position of powerlessness and from working creatively with one’s own limitations – financial and otherwise. Which makes me think of Waleria Sadkow, a young artist studying at the Art Academy Kassel (KhK), who works with trash and debris which she collects and recycles for her sculptural creations; the banana peel banner she showed at the open studios a few weeks ago still resonates with me.

To end this first letter, I would like to tell you about a reading I recently attended. Sophia Eisenhut’s new book of essays Spam in Alium just came out from Merve Verlag. Like Leung, Eisenhut has moved beyond an understanding of authorship that is centered on the production of original material, and like in Leung’s visual art practice, that’s not the point. It’s simply a condition of existence. I would be curious what you think of her wild mix of profound philosophical insight, dissection of language, investment in celebrity culture, drug enthusiasm, and body politics. It’s also very funny. As a teaser, I just give you the list of participants in a conversation titled “Mimesis is Murder / Diegesis is Innocent,” and let you imagine what the hell they would have to say to each other about “critique, representation, and crime”: Carla Lonzi, Ulrike Meinhof, David Joselit, Roland Barthes, Bruce Wayne dressed as Postwar Batman, Amber Heard, a can of Coke, Carl Schmitt, Robert Pattinson as Bruce Wayne, an incomplete cube by Sol LeWitt, someone named Bernadette, Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, and lastly, the narrator. Alas, there’s no English translation available yet, perhaps I should make that my summer project.

xo, Annette

PS: At the reading, Eisenhut wore high-heeled black Margiela tabi boots and a brown pantsuit. Encouraged by her example, I went straight to the Vestiaire Collective website and searched for tabi boots my size. I “hearted” two pairs: both mid-height heels, one black and the other silvery gray, sold by “fashion activists” in Belgium and Italy, respectively. Now I will go back to these images from time to time and look at them yearningly, until they disappear from my personalized page because someone else has snapped them up, leaving a ghostly, semi-transparent afterimage behind.

Annette Weisser is an artist and author.

Photo Annette Weisser