THE OPEN SPACE OF WE Tavia Nyong’o on “Writing on Raving: An Anthology”

Juliana Huxtable, 2025

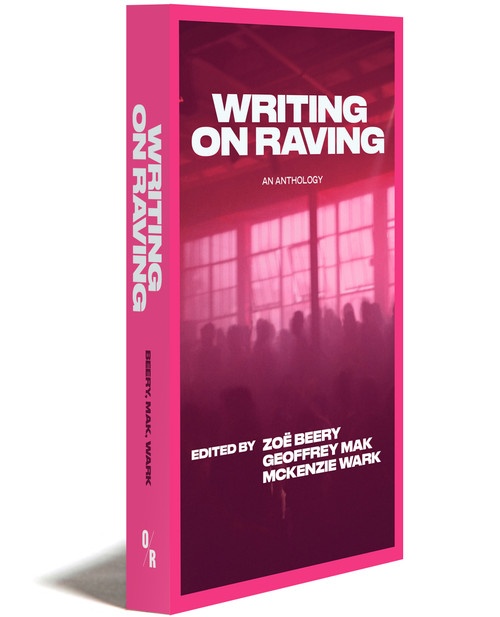

Is it possible to have a crush on a book? If so, I have a crush on Writing on Raving, an anthology of essays on the contemporary Brookyln rave scene edited by Zoë Beery, Geoffrey Mak, and McKenzie Wark. It began when I picked it up at my local bookstore, where I had dropped in on an errand for my mother, a constant reader. One book for her, and one book for me, I reasoned. I began reading my choice on the train ride home from the airport, after kissing mother goodbye, and almost missed my stop.

I have been obsessed with writing about nightlife since my college days, when I wrote my senior thesis on the vogue balls held in downtown New York. I was a candy raver in those years, dancing my tits off to legends like Junior Vazquez at clubs like the Tunnel, Twilo, and the Limelight. In those days, the dance pop supergroup Deee-Lite had been the tip of the iceberg of a chemical renaissance of dewdrops in the garden: raves held at big warehouses, back when it was still possible to throw warehouse raves in lower Manhattan. So the topic of Writing on Raving – which focuses on the contemporary rave scene – drew me in for nostalgia’s sake.

Twilo, late 1990s

What kept me there was the writing, beginning with hannah baer’s opening essay about heading straight from the airport to a club and having her phone nicked. Spending subsequent phoneless days musing about who the phone thieves were, baer writes, “I sometimes imagined them as mothers and grandmas with large breasts and bellies, swaying, serious about their task.” In the next essay, by Linn Tonstad, I encounter an equally delicious sentence as its opening line: “My mother, who turned seventy on Christmas Day of the first year of the pandemic, recently said to me that she had one regret in life: that she had never danced.” Tonstad goes on to reconcile her religious upbringing and raving through the apt paradox of “ascetic hedonism” found in the latter.

Each chapter is a short sugar rush of an essay, and I gulped each one down hungrily. Reading Writing on Raving is like arriving at a party, heading straight to the conversation pit, running into a lot of people you know who introduce you to the ones you don’t, and everyone is totally verbal. More than verbal, each new person has prepared a ten-minute discourse on what being there in that moment with you means to them, which they take out of their pocket and read like spoken word.

After making it halfway through the book in one train ride, I decided not to rush things, and to instead savor each writerly voice. For a book under 250 pages with minimal footnoting, written largely (with important exceptions) in the first person and about a single location (Brooklyn), Writing on Raving is astonishingly comprehensive. It is also very attuned to the sounds of the city. In her piece, Isabelia Herrera evokes the sounds of the Dominican diaspora – “dembow, merengue, salsa, and bachata” – and affirms the discourse of Martiniquan poet Édouard Glissant, who “captured how we lived sonic rebellion in our everyday speech, and in our everyday sounds.” The same could be said of Herrera, Gavilán Rayna Russom, Anne Lesley Selcer, and Jesus Hilario-Reyes, all writers who exemplify the verbal economy with which a Black Atlantic bacchanalia finds its way into print. Now that we have made techno Black again (at least some of us), it is a joy to encounter these textured voices corroborating and amplifying connections between musical genres, which flow up from the Global South to dominate dance floors in the creaking buildings of crumbling empires.

As the editors explain, each essay began as a talk given in a rave space before a party, meaning each writer faced the acid test of addressing their community in real time. That frame partly explains the uniformly high quality of the result. Many pieces, such as that by Zora Jade Khiry, are snapshots of a night at the club – in this case, the contretemps that ensue from going further than originally planned into the carry. “I should go home,” Khiry writes, “but I feel the urge to wring this carry out like a wet towel.” After reading this essay, I began using the word “carry” in a Khiry-esque way until my young friend began to laugh and make mock. What can I say? Sometimes mother has to carry, too.

The prismatic authority of each writer – dancers, deejays, promoters, historians, theorists, door staff, activists – means you can dip in anywhere and read the texts in any order. But I also sense a logic to the order the editors have chosen, ending with Shawn Dickerson’s “Safe Home,” a memoir of 40 years working in the nightlife of New York City. His relationship to nightlife was intergenerational, given that he grew up in his grandmother’s speakeasy in Philadelphia, learning from her how to run a door and set the vibe in a place. “I would watch her deal with problems,” he writes, “throwing people out. There was so much shade going on. She would have this whole signal system.”

While it’s certainly a living for nightlife professionals like Dickerson – and Chris Zaldua, who ran prominent rave spaces in San Francisco – ultimately all this scene work has the pragmatic ambition of getting people home safe. Facing gentrification, the Ghost Ship tragedy, and Covid lockdown, Zaldua asks himself, “Why do I put up with the bullshit? Why do I still show up?” He then offers this insight: “Through a nonlinear process, acts of commemoration and mutual aids bridge the chasm of loss, osmosing anguish and despair into kinship and, eventually, into celebration.”

That last word should startle. How do we turn loss, mourning, and melancholia into celebration? That question hit me differently when an acquaintance died over the course of my writing this review. He was someone I knew through his work, our shared mentors, and moments stolen belly up at the bar together at theory conferences, half in and half out of the game, watching and wondering at it. I poured one out for him and lit a cigar that had appeared in my rave bag. Hannah baer saw me do it and understood at once: it’s a grief cigar. And so it was. Celebration. Even in life, we are in death. And someone has stolen our phones, or at least temporarily bricked them.

Like any crush, I chased this book through the world, “love bombing” it with chance encounters and planned expeditions to wring the last drops of joy out of the hot, wet summer. The mystery of love in a world filled with the enraging heartbreak of deportations, genocide, technofascism, and the mind control of AI. My other book of the summer was Toni Morrison’s essay collection Mouth Full of Blood, which was dog-eared and warped by August. On page 47 of the US edition, Morrison declares: “I prefer not to adjust to my environment. I refuse the prison of ‘I’ and choose the open space of ‘we.’” If the picture of her dancing with James Baldwin is any indication, Ms. Morrison knew how to cut a rug. So, I take inspiration from her defiance of racism and fascism in the open shine.

Coursing throughout this volume is the talismanic word dissociation. Most essays comment offhandedly about ketamine and, less frequently, other drugs of choice that help induce the altered state of raving for those who partake. When the music is ecstatically right, as when Juliana Huxtable is playing a remix of “Funkytown” at 4:00 a.m. somewhere in Brooklyn and it seems to last for hours, we dissociate the prison of I and choose the open space of we. This space is a collective state, as Mx Oops explains with precise neuroscience in her contribution: “The dancefloor can be a place to regularly orient the direction of neuroplastic change.” Or as Slant Rhyme expresses the sentiment at the peak of her night out to hear Huxtable play, “there is an outburst of joyful clapping and uproarious whistling that reminds me that I am a tweaker chasing the night for a reason.”

In the Black radical tradition which raving sometimes acknowledges – especially now that Black trans women are at the center of DJ culture – the mouthful of blood we face is between the compelled performance for the master and the ring shout through which the enslaved refused dehumanization. I think about the precipice we all face, of becoming mothers and doulas for white folk eager to suck at the teat of Black rhythm and blues. And that spoils the joy of writing – which is to say thinking – about raving. I began with the dutiful intention of name-checking every contributor to this volume in my review, but I end by concluding that you should check them out for yourself. As the late great Prince said (borrowing from James Brown): You got to have a mother for me.

Zoë Beery, Geoffrey Mak, and McKenzie Wark, eds., Writing on Raving: An Anthology (OR Books, 2025).

Tavia Nyong’o is a writer, teacher, and curator based in Lenapehoking. His scholarly work explores the political unconscious of race and racism in performance from the 18th century to the present. His most recent book, Black Apocalypse, is out now from University of California Press. He has written about raving for e-flux and TDR, among others, and sometimes gets behind the decks as DJ Kseniya.

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of NEUROTICA, London, photo Courtney Frisby; 2. public domain