COURT REPORT Tobias Dias on “Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes” at Framer Framed, Amsterdam

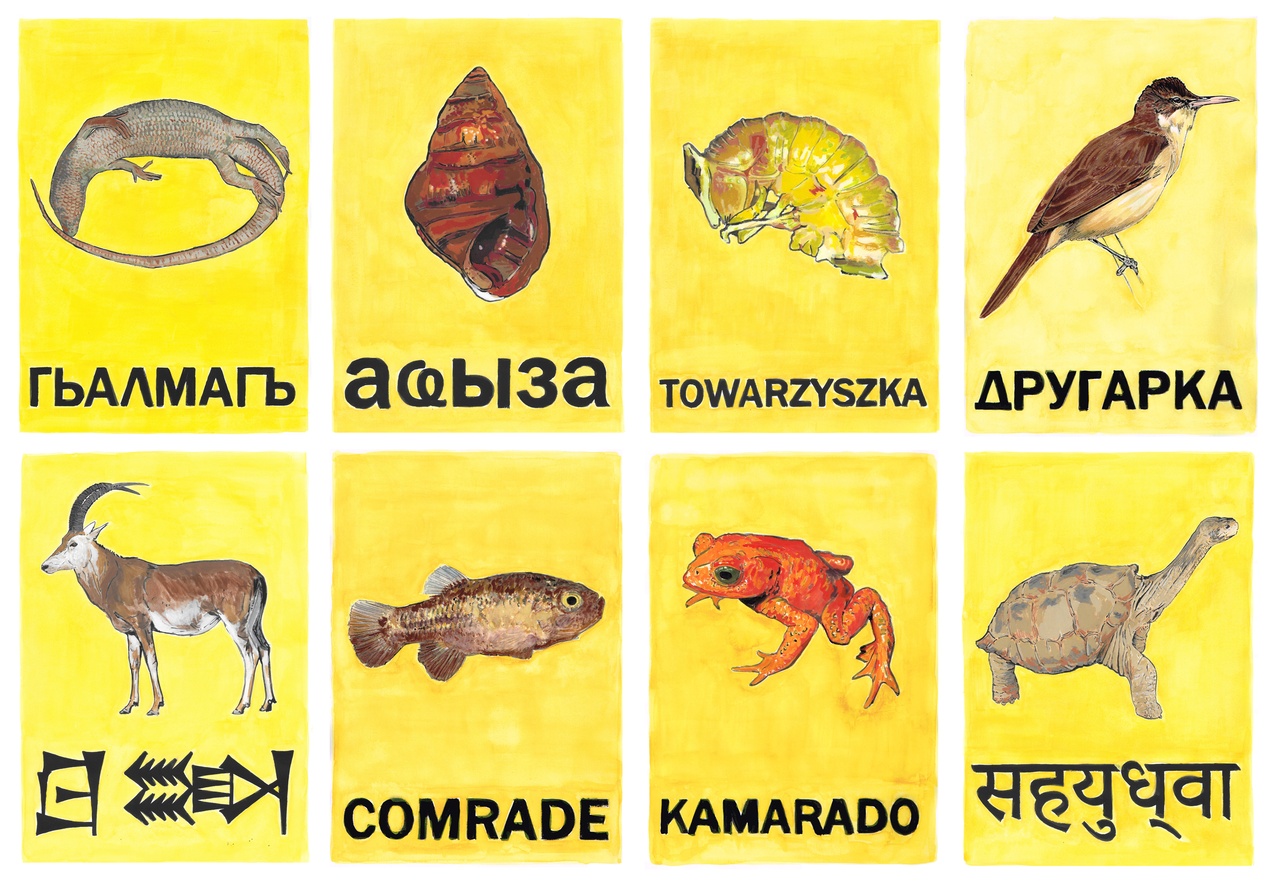

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, “Comrades in Extinction,” 2021

On September 24, 2021, the “Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes” (CICC) opened at the Amsterdam nonprofit art space Framer Framed. One month later, on October 28, the “more-than-human” tribunal began its four-day process of prosecution against the state of the Netherlands. Founded and inaugurated by Indian lawyer, academic, and activist Radha D’Souza and Dutch artist Jonas Staal, the alternative tribunal facilitated a series of juridical cases. On the docket were those responsible for the climate crimes of the state of the Netherlands and major multinational companies like Unilever, Airbus, and ING. In addition to D’Souza, scholars and writers Rasigan Maharajh, Nicholas Hildyard, and Sharon H. Venne acted as judges in the tribunal’s proceedings. Staal, on the other hand, enacted the role of the court clerk, reading aloud the prosecutions. Not unlike a loyal church singer, the artist-clerk, dressed in black from top to bottom, piously filled the void between one case and the next, thus evoking a constitutive gesture of the alternative court: the collective, collaborative, and counter-administrative labor that every social struggle requires if it is to be sustained. Such labor seems particularly important for contesting what lawyer and scholar Ted Hamilton has recently dubbed the “fossil law,” which enables and facilitates fossil capital’s perverse emission of greenhouse gases. [1] Engaging the juridical and its infrastructures as the CICC did might not appear as sexy and radical as sabotaging pipelines; yet, given how (fossil) law imbues social life, the alternative tribunal underscores that emancipatory struggle for climate justice needs more than just saboteurs, it also requires clerks.

This labor is bolstered by a material infrastructure; in this case, of the alternative court designed by Staal and Paul Kuipers. Beyond the exhibition’s days of hearings and collective performative labor, this is what amounted to the artwork; an installation comprised of a cork construction arranged in biomorphic curves. Each of its seats bore a metal rod holding a sign depicting and representing a particular extinct species, each with the word “comrade” in different languages. Here, members of the court – the public “art spectators” that together constituted the jury – were invited to sit and participate in the assembly, facilitating the meticulously planned hearings among fellow non-human witness-comrades from the (deep) past, such as “Comrade Eriocaulon inundatum,” “Comrade Mauritius Grey Parrot,” and “Comrade Rodrigues blue pigeon.” These non-human comrades – which functioned as both witnesses to and evidence of climate crimes – also comprised their own archive, titled “Comrades in Extinction,” accompanying the extensive text material delivered to the jury members. Between the extinction of these plants and animals, the ammonite fossils, and the oil basin that functioned as the lower stage of the courtroom, visitors quickly recognized that they had not just entered an alternative court, but also a graveyard, the seats and signs acting as gravestones. Together with the human victim-witnesses from different areas of the Global South who spoke throughout the hearings, the infrastructural arrangement of these non-human comrades not only testified to the “death cult” of fossil capitalism, but also to what it might mean to struggle in the era of the Sixth Extinction.

In contrast to Forensic Architecture’s work, for example, the CICC didn’t so much emphasize the meticulous counter-forensic labor of excavating evidence as offer the building and facilitation of a para-juridical and counter-public infrastructure. What mattered, to paraphrase Bruno Latour, was the very enactment of making evidence public – that is, presenting evidence in videos (and subsequent hearings), produced by the victim-witnesses themselves, of climate crimes that have evaded the current regime of international law, which acknowledges neither the notion of ecocide nor the agency of non-human life forms and their interdependency with humans. Often taking the aesthetic form of DIY videos (and a few PowerPoint slides), these videos were, however, not presented as artistic in and of themselves – a conceptualization, for example, at play in the recent collaboratively staged Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness in New Delhi. Described as a “witness statement” within the strictly coordinated alternative court room, this framing befitted the para-juridical and counter-administrative logic of the tribunal while at the same time allowing an illuminating and tragic polyphonic assemblage of epistemic-aesthetic effects and voices “from below” testifying to various climate crimes: from the State of the Netherlands Bilateral Investment Treaties with Mongolia, which allowed companies to disembowel the earth and deplete water resources in the Gobi Desert, to Unilever’s vast discharging of mercury and massive deforestation in the Kodaikanal region of Tamil Nadu in India.

Jonas Staal and Paul Kuipers, “Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes,” 2021, architectural model

Informed by D’Souza’s 2018 book What’s Wrong with Rights, the legal framework of the tribunal strived to identify the disastrous shortcomings of international law and established the “Intergenerational Climate Crimes Act.” In her book, D’Souza starts by identifying the convergence of the “motto” of many social movements since the 1990s – that “every wrong must have a corresponding ‘human’ right” – and the most powerful states and capitalist corporations campaigning for human rights. [2] Her aim is to analyze the economic, legal, and political underpinnings behind both sides’ pursuit of rights. D’Souza anchors this analysis in a much wider critique of the very discourse of rights, which, as she argues, “owes its birth to that moment when land was transformed into a commodity and hundreds of thousands of people were evicted from the places they called their ‘homeland.’” [3] From this process of primitive accumulation, land transformed from a “relationship into a thing,” becoming a commodity and private property that disrupts the very “glue that holds people and nature together to form places.” [4] And as D’Souza argues, this process – not least enabled by the internationalization of the “abstract legal forms” of rights, and the adding of the prefix “human” – reached its vulgar dialectical reversal in the postwar capitalist regime of accumulation: as a relic of 19th-century legal cases and amendments to the US constitution, the fact that corporations today act as “right-bearing persons” and even carry citizenship has become an essential functional attribute of the continued reproduction of the global capitalist system of climate crimes.

One of the CICC’s main gestures is its critical inversion of the operative legal system undergirded by anthropomorph corporations and states – less by including non-human life forms into such legal systems by ascribing rights to nature (as in the example of Ecuador’s and Bolivia’s constitutional amendments in 2008 and 2012, respectively) than by contesting the very anthropocentric and property-based principles of law (as epitomized in the liberal discourse of the Rights of Man inherited from the Enlightenment). The artistic détournement of the “social form” of the tribunal, as Claire Bishop has called it, is, of course, far from an unfamiliar genre – neither in contemporary art nor in the so-called “modern” history of art. Since at least the Paris Dada enactment of the so-called Barrès Trial in 1921, the performative play of judges and juries within the setting of an alternative courtroom has served as an effective artistic strategy for provoking public discourse. Of course, the sine qua non of such subversions of the social form of the tribunal – and the gesturing toward the history of popular tribunals this involves – is the (re)inscription into the social form of the art institution. If this could be said to be a constitutive contradiction of much contemporary art engaged with the tribunal form, the CICC seems to parse out the critical potentialities and implications of such a practice in an exemplary manner. Translating some of D’Souza’s “theoretical models into spatial morphologies,” it not only spatializes and gives form to the violent structuring and distribution of legal agency, victims, and ecocide in deep pasts, presents, and futures. Enacting a more-than-human tribunal, the assembly of the CICC also turns the art space into what theorist Marina Vishmidt has termed an “infrastructural critique”: an expanded collaborative, transdisciplinary, and alter-institutional art practice supported by the court installation in which artists, activists, academics, progressive judges, and social and Indigenous movements resided.

Radha D’Souza at the “Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes,” 2021-22

As is often the case in Staal’s “propagandistic” works, the CICC hereby ends up manifesting a porous border between a complicity with the often generic political gestures of the “institution of critique” – which has increasingly taken a “socially engaged” form – and a practice strategically appropriating this very institutional complicity for other purposes. The case to be made here is not that D’Souza and Staal should have better accommodated for their institutional entanglement, as if a return to a classic institutional critique was desirable. Just as Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, Staal knows very well that worrying too much about conforming to the art institution more often than not manifests a “fear of the general antagonism” – that is, a fear of being entangled too intimately in the institution and thus unable to draw boundaries that allegedly secure critical distance. For better or worse, the risk of being trapped in a participatory culture of collaboration dressed up in progressive rhetoric – as in the pejorative sense of the performance of the political – is the price to pay for large-scale installations like the CICC. At no point in time, however, did the CICC leave the impression of such an aestheticized Ersatzpolitik. Rather, its internal transgression from what is normally possible at an art institution facilitated an alternative way of “being complicit with others,” as Harney and Moten would say. Less as a stage for achieving climate justice, and more as a place for enabling a continued struggle for it.

“Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes” at Framer Framed, Amsterdam, September 24, 2021–February 13, 2022.

Tobias Dias is a researcher, editor, and writer based in Aarhus, Denmark.

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of Radha D’Souza, Jonas Staal, and Framer Framed; 2. Courtesy Radha D’Souza and Pluto Press; 3.-4. Courtesy of Framer Framed, photos: Ruben Hamelink

Notes

| [1] | See Ted Hamilton, Beyond Fossil Law: Climate, Courts and the Fight for a Sustainable Future (New York: OR Books, 2022). |

| [2] | Radha D’Souza, What’s Wrong with Rights? Social Movements, Law and Liberal Imaginations (London: Pluto Press, 2018), 3–5. |

| [3] | D’Souza, What’s Wrong with Rights?, 5. |

| [4] | D’Souza, What’s Wrong with Rights?, 5. Emphasis in original. |