THE HYPERAESTHETICS OF WITNESSING Tobias Dias on Forensic Architecture at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark

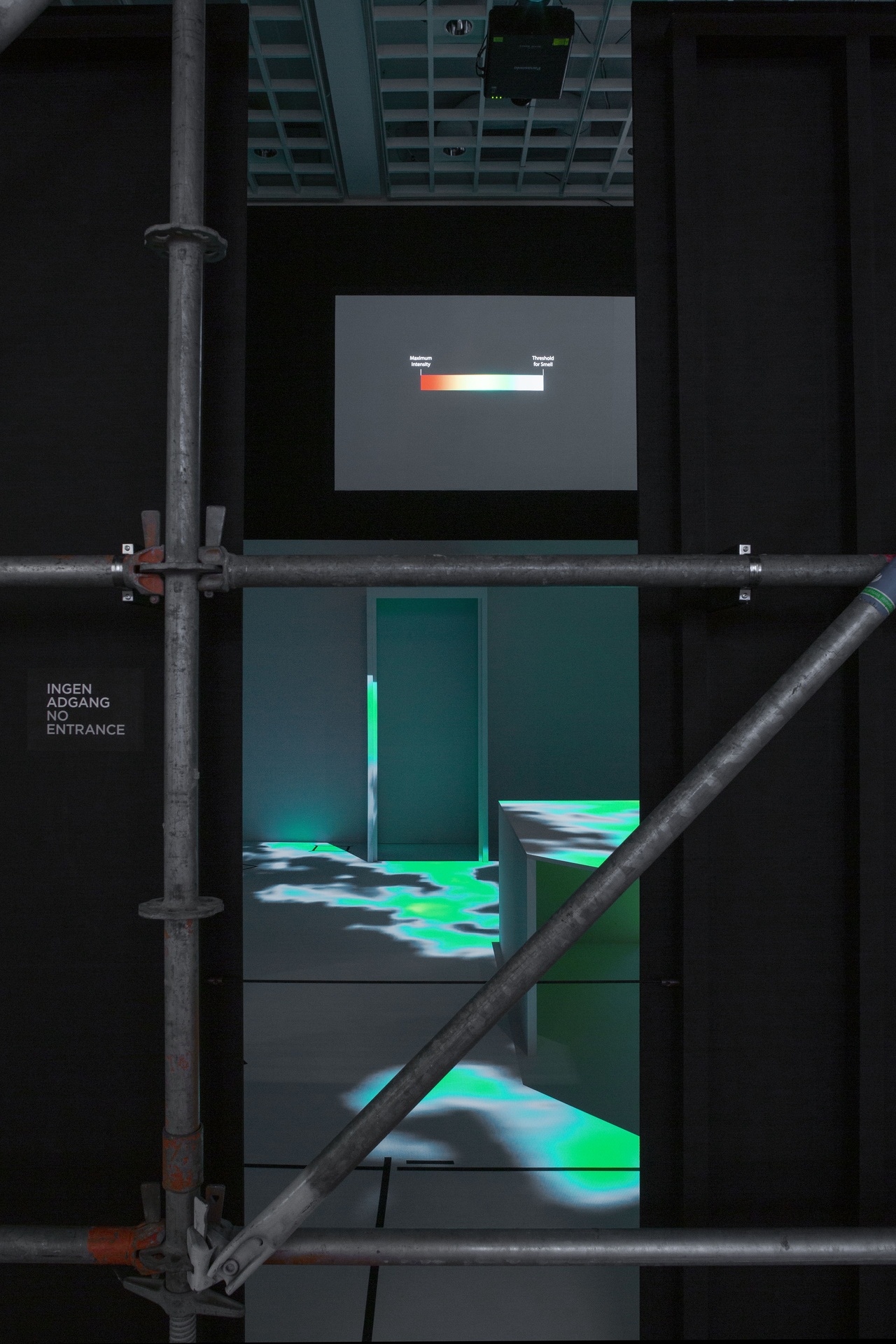

“Forensic Architecture: Witnesses,” Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark, 2022, installation view

Entering the wide-open doors at Forensic Architecture’s exhibition Witnesses at Louisiana, one is immediately confronted with the reverse side of a huge, curved screen. Following the pathway at the right side of the curve, one is then led to a classical and subtly arranged museum vitrine illuminated by suspended lights from above. The refined arrangement of images displays the quite extraordinary and even spectacular 1985 discovery of the body of the Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele, the so-called “doctor of Auschwitz,” exhumed in São Paulo; the images were produced through a videographic technique of “face-skull superimposition,” which was further developed for that investigation by pathologist and photographer Richard Helmer, who helped substantiate the verification of Mengele’s bodily remains. [1] The technique that enabled the object-skull of the subject to speak in its own peculiar morphological language thus came to manifest how “bones make great witnesses,” as is stressed in a quotation of the forensic expert Clyde Snow that appears in a wall text. These words were not expressed in the Mengele case, but rather in the context of civilian Argentinian activists, the so-called “gravediggers” who, around the same time of the discovery of Mengele’s bones exhumed bodily remains of victims of violent repression carried out on South American soil.

As FA director Eyal Weizman hints at in the 2016 book Forensic Architecture, these two instances amount to the Urszene of the research agency’s methodological ethos, an evolving but largely unfulfilled emergence of a kind of counter-forensic aesthetics that now frequently appears in art spaces. The means of these activist-technoscientific investigations is considered by the agency as a quintessential aesthetic act in two senses of the term, as recently expounded in the book Investigative Aesthetics, written by Weizman and media theorist Matthew Fuller; it is a sentient attunement toward things, of becoming sensitized toward the “language” of materiality and its peculiar “modes of sensing” as well as a way of experimenting with methods to allow these human and non-human sensory environments to become visible, audible, aestheticized and thus part of a process of “sense-making,” for example, presented at an art institution. [2]

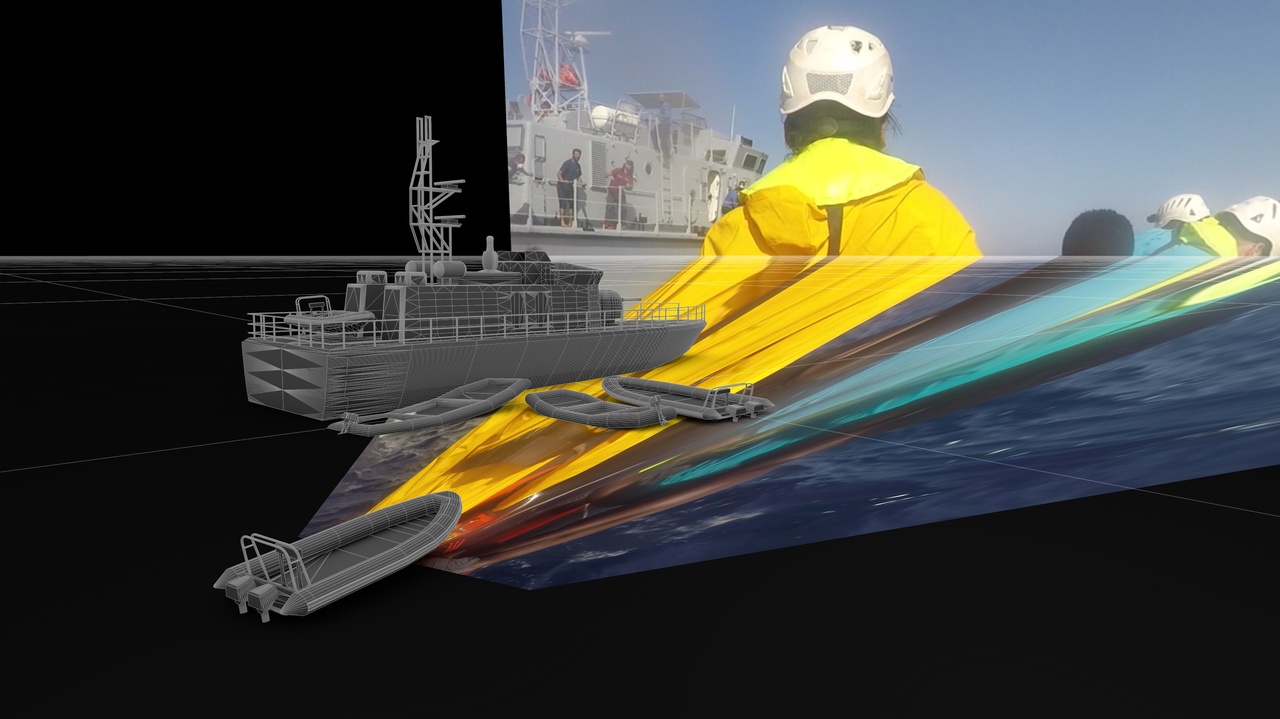

Forensic Architecture, “Sea Watch vs Libyan Coast Guard,” 2018

Following the curved screen’s twisted pathway to its front display in the first exhibition room, visitors are invited to watch a condensed video essay weaving together reflections on how the aesthetic practice of FA renders neglected and often obfuscated forms of witnessing part of a new “distribution of the sensible,” as Jacques Rancière would say. Borrowing a notion from Fuller and Weizman’s book, one could say that the exhibition constitutes a hyperaesthetics of witnessing in the sense of “amplifying” and “multiplying” forms of bearing witness. [3]

On two levels, both of which literally reside underground, the exhibition unearths the very evidentiary mechanism of FA’s engagement with acts of witnessing. Along the way, the non-human material sensors bearing witness comprise a wide spectrum: from the slow violence of cracks in buildings, to the crops affected by the spraying of “crop-killing herbicides by air,” to the more abrupt and transitory traces of violence such as wakes (as in the wave generated from a boat moving) and clouds from bombs, teargas, and white phosphorous. At the same time, it allows a more complex and situated investigation of the ways in which humans are witnesses, as in the “situated witness” at play in video footage displaying a shipwreck in the Aegean Sea of a migrant boat recorded by one of the survivors, or the completely “anaesthetized” prisoners of the notorious Saydnaya prison in Syria. Through interviews with some of the former prisoners conducted within the setting of architectural and acoustic models of Saydnaya, FA helped reconstruct this violent and traumatic infrastructure.

As the fifth exhibition in Louisiana’s “The Architect’s Studio” series, curated by the research fellow and former deputy director and lead researcher of FA, Christina Varvia, together with two curators at Louisiana, Kjeld Kjeldsen and Mette Marie Kallehauge, the show thus not only displays but expands and elaborates on a particular angle of the rather unusual architectural practice of FA: how the deconstruction of the basic judicial tenets of the legal system – from notions of expert objectivity and neutrality to disembodied, abstract testimony – are intimately linked to the construction of models manifesting ways of “producing” witnesses and evidence otherwise. Here, the exhibition room is less a forum that merely documents or illustrates the various cases investigated by FA than an aesthetic and curatorial reflection on the methods undergirding FA’s practice, in the ancient sense of methodos, which literally translates as “the way to follow” – a way that in the case of FA is always directed and (re)invented by a sensitivity toward the singularity of its concrete cases. Neither a prescription nor a transcendental reflection, this path, or these paths, thus comes to constitute its own peculiar “montage of attraction” of past forms of evidence and testimony that crystallize, or at least make thinkable, new potential forms of counter-forensic evidence gathering.

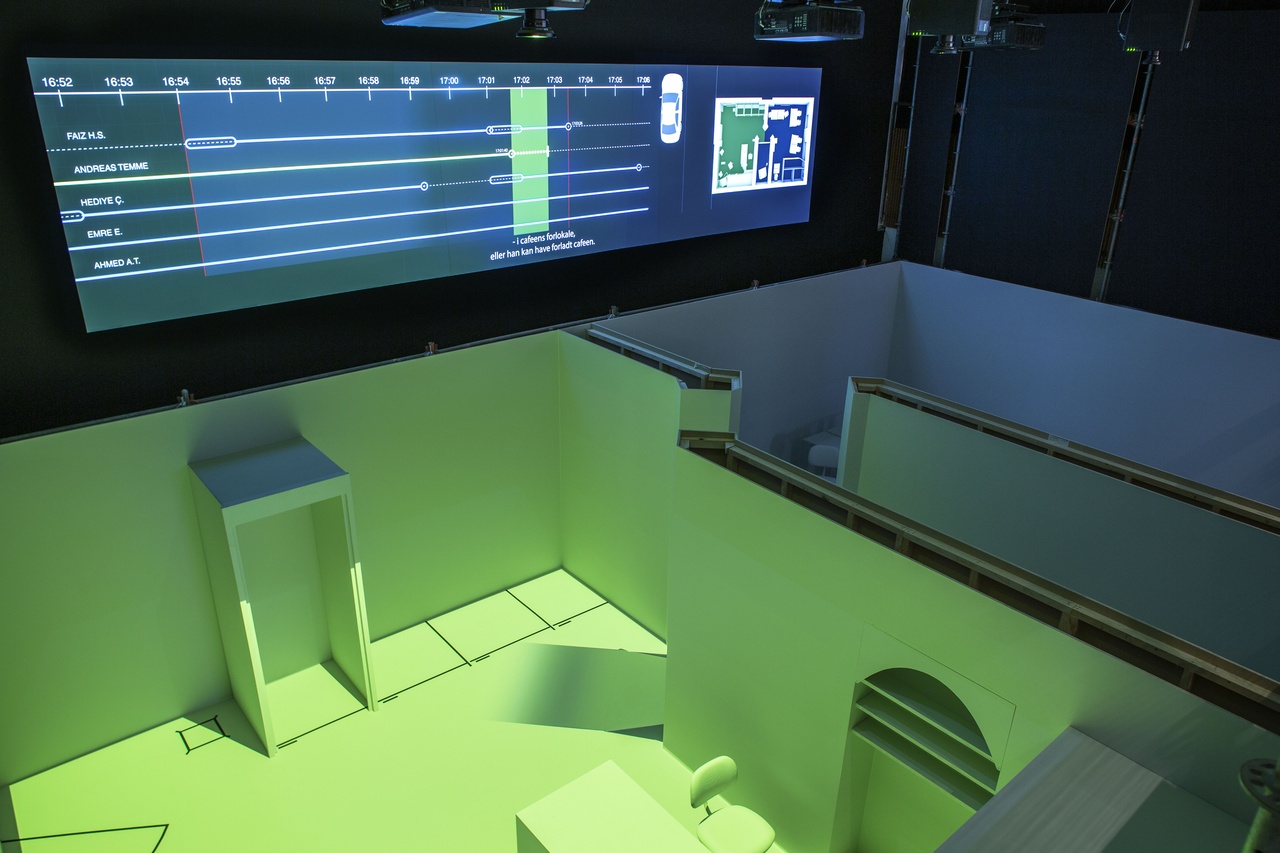

Forensic Architecture, “The Murder of Halit Yozgat,” 2017

The predictable irony here is that exactly this productive and strategic undoing of state and corporate forensic practice, as well as the legal system underpinning it, in alternative forums of “weak objectivity,” is what makes FA’s practice highly vulnerable to attacks and accusations from the institutions they contest. The particularities that bolster the reliability and potency of their counter-forensic “truth production” are also the particularities that most expose them to crude denouncements of the omnipresent “dark epistemologists” of our “post-truth” age, whether they be politicians, security services, military departments, or multinational companies. [4] A key reason for such denouncements should obviously be found in FA’s “aesthetic” repertoire, their digital models, timelines, videos, and other “works” – they also dub this the “architectural image complex” – largely legitimizing their frequent appearance at art institutions and even the disputed status of “art” attached to the practice of FA. This aesthetic repertoire is obviously fertile ground for contradictions to evolve, to be discredited by referring — as a German journalist and politician did—to the agency as an “art group” with a “work of art full of mistakes” or — as an art critic put it — as presenting “evidence, not art.” [5]

FA is, of course, fully aware that both the courtroom and art institutions are “contaminated” by various conflicting and intermingling structuring logics that must be navigated tactically. Adept at self-conceptualization, Weizman has in this context suggested the notion of “open verification” in order to capture how FA’s multidisciplinary agency “[r]ather than objectivity’s ‘view from nowhere’ [...] seeks the meshing of multiple, subjective, located, and situated perspectives.” [6] The intimate connection between technoaesthetic and technoscientific forms of knowledge production, and the complex and experimental web of “truth production” this leads to, depends on the ongoing organization of collective infrastructures of civil organizations, journalists, experts, and other practitioners persistently built through open-source investigations. For FA, exhibitions at art institutions are thus both conditioned by and an active part of a practice of “socializing the production and dissemination of evidence,” an effort to find “common ground” or even an “aesthetic commons.” [7]

“Forensic Architecture: Witnesses,” Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark, 2022, installation view

How and to what extent is this process of socialization imbricated into the exhibition room? This question runs through FA’s exhibitionary practice, not least at the Louisiana venue, where the curatorial team seems to have made quite an effort into enhancing the “aesthetic” and “artistic” repertoire of FA’s practice. The question could be said to epitomize a tension between the expanded and boundless scope of its “aesthetic practice” and the differentiating logic of the art institution in the age in which its semblance of autonomy is becoming ever more difficult to retain and thus consequentially a desperate fetish value in itself. [8] A reflection of this contradiction could be seen in a perhaps minor but nonetheless symptomatic curatorial choice: the exposition on the museum wall of selected paper sketches of the Saydnaya prison drawn by the anaesthetized prisoners themselves in the initial phase of reconstructing their memories. What stood out here was not just the gestures of singular lines drawn on sheets of paper or the thin materiality of the paper itself. To a much larger degree than elsewhere, these sheets of paper, containing fragmentary and courageous acts of drawing that struggle to delineate the material infrastructure of trauma, allowed a glance into the very open and unpredictable process of witnessing. Of course, this could also be said of many of the other “works” rendered possible by the modeling and synchronization of a vast quantity of images, data, and information. However, whereas the videos, photographs, and 3D models often gave the appearance of a synthetic unity or “open works”—as Umberto Eco would say—of massive datasets assembled, curated, and processed in the London studio of the activist research agency and then exhibited in the museum room, the “untreated” nature of the paper sheets far more testified to the tiresome labor and social process that give life to the exhibited “works” in the first place. Despite the overarching curatorial concept of “The Architect’s Studio,” this open experimental and social process seems strangely downplayed throughout the exhibition.

The point here is not to fall into the trap of a romantic critique of synchronization or modeling as the tragic evaporation of the singular (sheets of paper in a world undergoing a process of digital transference) – quite the contrary. What needs to be emphasized is rather the irony that it was in the slightly awkward but nonetheless productively placed “authentic” traces of the work of the hand that most clearly testified to the collective and social practice of the many hands assembling witnesses in the far more frequent techniques of digital and computational modeling, synthesizing, and synchronizing. For FA, to model or synchronize does not imply homogenization but relationality and “hyperperspectivity.” It is, in other words, a fundamental technoaesthetic operation that in itself testifies to an expanded and complex process of socialization, a process of fleeting common grounds. However, this central aspect of socialization tended to smother throughout the show. How could this be?

We could conceive the difficulty in integrating the process of socialization within the exhibition room as a reflection of the antinomy, as already hinted at above, undergirding the very practice of FA: On the one hand, it is a potential outcome of the conversion of FA’s practice into aesthetic objects of the “contaminated” exhibition room. On the other hand, we immediately need to acknowledge that what grounds this outcome is also what demarcates a new porous strategic field for using the art institution as an infrastructural resource for an epistemic-aesthetic mode of practice that reaches far beyond it. At best, the dominant logic of the exhibition room is here altered, “compromised” from the site of FA’s practice; it is effectively turned into just one link within a complex and productive web of multiple infrastructural sites such as the studio, the lab, the courtroom, the forest, the ocean, or the street, collectively weaved together in various ways in the practice of FA. We are here far beyond the avant-gardist credo for sublating the division between art and life for the simple reason that “art” just amounts to one site within a wider infrastructural network that comes into being through FA’s organization.

“Forensic Architecture: Witnesses,” Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark, May 20–October 23, 2022.

Tobias Dias is a postdoctoral researcher, editor, and writer based in Aarhus, Denmark.

Image credit: © Photos 1, 3, and 4 courtesy of Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, 2. photo courtesy of Forensic Oceanography and Forensic Architecture

Notes

| [1] | For more on this, see Thomas Keenan and Eyal Weizman, Mengele’s Skull: The Advent of a Forensic Aesthetics (Berlin: Sternberg; Frankfurt am Main: Portikus, 2012), 19. |

| [2] | See Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth (London: Verso, 2021). |

| [3] | Fuller and Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics, 57. |

| [4] | Eyal Weizman, “Open Verification,” e-flux Architecture, June 2019. |

| [5] | Pitt von Bebenburg, “Rätseln über Temmes Anwesenheit,” Frankfurter Rundschau, August 25, 2017; Hili Perlson, “The Most Important Piece at documenta 14 in Kassel Is Not an Artwork. It’s Evidence,” Artnet, June 8, 2017. |

| [6] | Eyal Weizman, “Open Verification,” e-flux Architecture, June 2019. |

| [7] | Ibid. |

| [8] | For a more thorough reflection on this, see Jacob Lund, “Exhibition as Reflexive Transformation,” OBOE Journal On Biennials and Other Exhibitions 3, no. 1 (2022). |