A Value-Theoretical Banksy by Isabelle Graw

Banksy, Auktion von „Love is in the Bin“, Sotheby's, London, 2018

1. Theoretical premises

The following is based on the hypothesis that the products of visual art – and thus also Banksy’s “Love Is in the Bin” (2018) – have a special value-form that differentiates them from other goods. In my view, although the value of artworks and the value of ordinary goods can both be traced back to a form of labor that also may be immaterial if it takes the form of ideas, concepts, or communication, nevertheless artworks – as distinct from other goods – are capable of suggesting the presence within themselves of an artistic labor (that is in truth absent). Rather than with ordinary commodities, in which the work expended on them remains largely hidden, artworks give the impression that they “contain” within themselves the very artistic labor on which they are determined. Works of art nourish, in other words, the (vitalistic) idea that their value has physical substance. This, however, is a materially induced idea, and one which does not arise by chance. Artworks trigger this vitalist notion by giving it a material vehicle and by intervening in their respective contexts in a specific way.

Their value seems to be present in tangible, material form, and it seems to be based on a specific intervention. The fact that artworks nourish this assumption of their “intrinsic” value is also directly related to their structural idiosyncrasies. In contrast to serially produced luxury goods, artworks are material one-offs [1], each one ascribed to a singular author. It is the signature that directly links this product back to its author, such that it is associated with their comparatively privileged artistic labor. Although artistic labor may now be established as the blueprint for creative work, the former involves a far greater degree of self-determination. Economic constraints may extend into the artist’s studio, but artists can still largely determine both their own working hours and the content and purpose of their products: the creative worker in an advertising agency can only dream of the freedom associated with artistic labor. Because In contrast to the artist, she has no material product as a result of her labor. If the artist produces art in the traditional sense, she can present a material product as the result of her work, of which she is considered the author. And these privileges associated with artistic work are deposited, conversely, in the material product of art.

However, the special value-form of an artwork is not only founded on the specificity of artistic labor; it is also dependent on its reception. For the specific intervention of a work of art in its context to be considered significant (i.e. symbolically valuable), a collective, affective force – one the French economist André Orléan calls “affect commun” – must have been directed towards it. And this receptive power – which functions mimetically, per Orléan – invests itself only in certain objects, such that others can be left behind. For a work of art to be associated with value, certain conditions in terms of production aesthetics (material, long-lasting one-off product of privileged artistic labor) must be present, as must the receptive forces that desire it.

Banksy, „Love is in the Bin“, 2018

2. “Girl with Balloon” as a Thing of Value

Taking this value-theory proposition as a springboard, it can be said that Banksy’s painting “Girl with Balloon” (2006) had already fulfilled the essential prerequisites for the genesis of art’s special value-form, even before its highly publicized shredding at the Sotheby’s auction. Both the uniqueness principle (so essential for the special value-form of art) and materiality were present, the latter in the form of acrylic on canvas.

According to Sotheby’s, this image represents a rare example of a Banksy original, even despite the fact that its motif, seemingly very popular with Banksy fans, [2] has previously circulated as graffiti.

From a value-theoretical perspective, it is the very fact that this motif stems from graffiti that augments the image with “street credibility.” Or, to speak in terms of reception theory: being anchored in a graffiti milieu, the frisson of illegal activity can be projected onto this image.

With its formal language, "Girl with Balloon" demonstrates the signature Banksy style of the early 2000s, being one of those works that Banksy (or his employees) [3] stenciled rather than painted with a free hand. And despite Banksy’s much-vaunted anonymity [4], it is attributable to an author named Banksy. The pervasive nexus that in my opinion underlies art’s special value-form – that of material product and singular creator – likewise asserts itself here. Post avant-garde attempts to question authorship have not, in truth, managed to undermine the author principle, which has on the contrary been reformatted and expanded. According to Banksy’s dealer, a buzz has been created by factors such as his anonymity, with this buzz likewise making a positive contribution to the valorization process. Art’s value is stimulated by such narratives; and this has been the case since the early modern era, when equivalent legends and anecdotes about artists drove the process of value attribution.

The spraypainted visual motif – and especially its white, foggy, “painterly” background – also suggest they can be traced back to artistic labor. This image thus nourishes the central (vitalistic) notion of value-creation: that the artist’s absent, tangible work is somehow present in it. Its value once again appears to have substance. However, the work stored within "Girl with Balloon" (apparently) ranges from specifically artistic to general work, in my opinion further increasing its ability to fascinate. On the one hand, Banksy has long operated as an entrepreneurial [5] artist who successfully markets prints and gadgets on his website. It is no coincidence that the name Banksy contains the word “bank” – giving the impression that he seeks to identify himself with the workings of a financial institution.

At the same time, however, and in contrast to the entrepreneur, he also behaves as a rebellious, rule-breaking anarchist artist who spraypaints in defiance of the prevailing model of property ownership. [6] In his case, the freedoms and rule violations that are granted to him as a graffiti artist enter into a perfect symbiosis with the model of the corporate artist, once again proving that subversive rebellion can be easily marketed under capitalism.

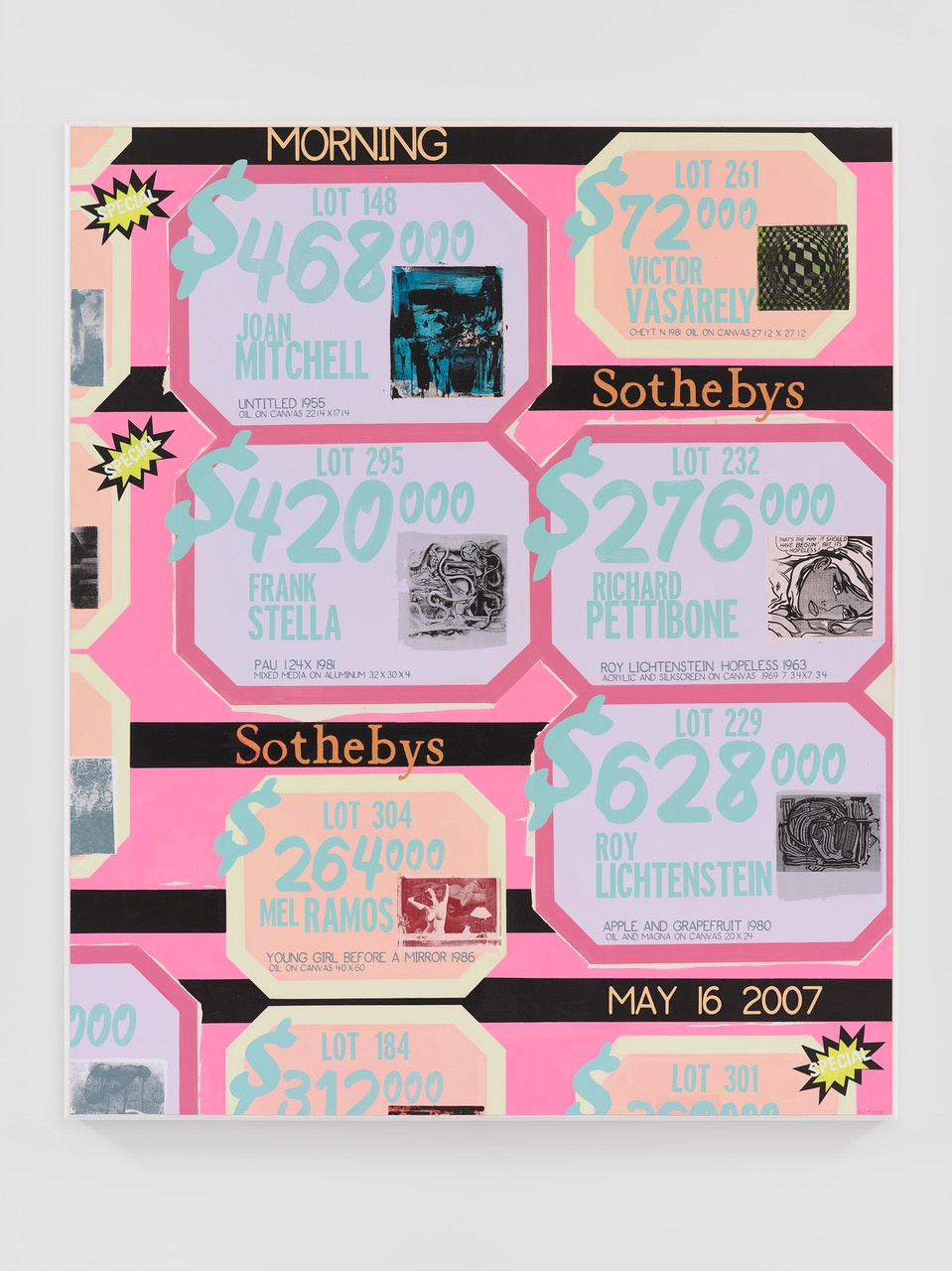

Kerry James Marshall, „History of Painting (May 16, 2007)“, 2018

3. Simplistic Value-reflection

Viewed more generously, “Girl with Balloon” could also be described as a work which addresses its own value, doing so however (sadly) in a decidedly facile manner. The old-master styling of the image’s framing can thus be read as a (richly trivial) symbol for the value-increasing crossover from graffiti to the sphere of high art and auction. His infantile, easy-to-grasp iconography – the flying red balloon in the shape of a heart, with the figure of a child reaching for it in vain – could also allude to a value that is similarly impossible to capture due to its relational and metonymic character, as described by Karl Marx. Like the red balloon in this picture, which is full only of air and could burst at any time, value too is built on sand. We could also read this visual scene as a deliberately banal allegory of unrequited love, since the object of love here eludes desire. In its trivial symbolism, this heart communicates formally and aesthetically with Jeff Koons’s “Hanging Heart" (1994-2006), which also set a new auction record in 2007. At the same time, however, "Girl with Balloon" also seems to make fun of those art lovers who take such works (whether by Koons or Banksy) seriously and spend serious amounts of money on them. Banksy’s previous work “Morons (White and Gold)” (2006) represented an auction scene, with a picture framed in old-master style stating to potential bidders: “I can’t believe you morons actually buy this shit.” From this “speaking” image, it is the artist who seems to turn himself to his auction audience, who he insults in an épater le bourgeois-like manner (“you morons”), who will of course then adore him in return.

Jeff Koons, „Hanging Heart (Red/Gold)“, 1994-2006

4. Value Destruction as Value Creation

How can the shredding act be interpreted in terms of value theory? According to Banksy, the shredding mechanism built into the work was intended to destroy it completely, which, as is well known (and due to an alleged “error”) did not succeed. Such artist statements should, however, be enjoyed with caution and not taken at face value. But in terms of value theory, it makes a considerable difference whether this picture’s materiality is completely destroyed or whether its central motif, the heart, remains visible like the now-shredded figure of the girl. Despite the partial destruction of the canvas, “Love is in the Bin” (2018) still ensures that value can be attached to a tangible, material vehicle. And going even further, the image elements shredded into strips function as relics of an act that is now integrated into the work – like a form of surplus value.

Accordingly, after the first shock was overcome, the auction house was able to proudly announce that the Banksy work was historically the first work of art to have been produced during an auction. [7] The fact that it carries within it an event of apparent destruction of value – an event that attracted worldwide attention – means that it has now become an icon, proudly presented by the Frieder Burda Museum in Baden Baden. Its market value is also said to have risen enormously since the auction. However, the media spectacle, which resulted in the partial self-destruction of an artwork in the auction hall, formed a striking contrast to attitudes in art history and art criticism, which continue rather to shun the Banksy phenomenon. There is accordingly little serious writing on him. The market success of this work also proves that art criticism’s skepticism about Banksy’s artistic significance carries little weight in the auction room. Orléan´s collective desire – which is directed only at certain works of art – is clearly not to be understood as a uniformity but as something split within itself. And in certain segments of the art world, such as the secondary market, the desire of experts has less weight than that of collectors, agents, and the media.

Has Banksy’s act caused a credibility problem for auction houses? Yes and no. It was possible to sense a kind of Banksy-effect in the short-term, with many lots in the following auctions being declined even where this would not necessarily have been expected (such as with works by Christopher Wool, Lucio Fontana, and John Baldessari); perhaps the sight of the partially destroyed canvas cast a lingering doubt among bidders as to the supposed intrinsic value of artworks.

At the same time, however, Bansky’s act also reveals the limits of a subversive act in which the artist, via his image, infiltrates the auction sphere as a voluntaristic subject in order to outsmart it. Banksy’s attempt to withdraw the value of its material basis led, foreseeably, to an expansion of its zone of value. The manifold artistic attempts at value destruction that have taken place throughout the history of art have always proven to generate value; [8] what is interesting about Bankys’s act, however, is that it remains within the value sphere instead of aiming at an imaginary point located beyond it, as artists often do today. But instead of subversively infiltrating the sphere of value like Banksy, thus overestimating the artist’s authority and underestimating the structure of value formation, it would, in my opinion, be more fruitful to see yourself as part of a context of value, the norms of which you simultaneously question by way of a (fictitious) distance. In this way, the values and norms of this sphere could become destabelized, perhaps even losing their validity in the long term.

Translation: Matthew Scown

Isabelle Graw is the co-founding publisher of Texte zur Kunst.

Notes

| [1] | This even applies to immaterial works such as performances. Like relics, props, or video documentation, these ensure the presence of a material vehicle to which their value can be attached. |

| [2] | See Martin Bull: This Is Not a Photo Opportunity: The Street Art of Banksy, Oakland, 2015, p. 169. |

| [3] | “Banksy doesn’t actually execute a lot of the street art pieces anymore”: Will Ellsworth-Jones: Banksy: The Man behind the Wall, New York 2012, p. 179. |

| [4] | Cf. Will Ellworth-Jones: Banksy: The Man behind the Wall, New York, 2012, p. 104: “his anonymity creates a buzz.” |

| [5] | See Robert Clarke: Seven Years with Banksy, London 2012, p. 61: Banksy is described here as a “corporate artist” who circulates screen prints, canvas paintings, stickers and books as exhibition concepts. |

| [6] | See Simon Hattenstone’s interview with Banksy: Something to Spray in The Guardian, July 17, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/artandesign/2003/jul/17/art.artsfeatures |

| [7] | See Anny Shaw: Banksy Seller’s Stringent Instruction for Sotheby’s Revealed, in: The Art Newspaper, October 17, 2018. |

| [8] | One of many examples of the expansion of the zone of value described here would be John Baldessari’s legendary “Cremation Project” (1970), where the burning of his pictures produced a relic of the act – the urn with ashes. There are also documentary photos of the act, providing a material vehicle for its value. The burning of his images also represented the originary scene of his conceptual approach and, for art history, one of his most significant actions. |