Rosemarie Trockel

Cliché (2023)

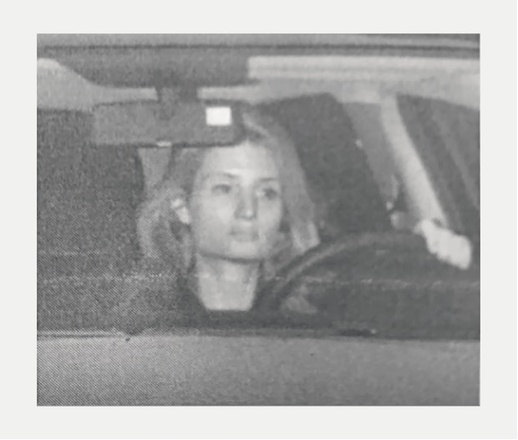

That Germans love their cars more than their children is a tired cliché – and yet the nation has been embroiled in a controversy for years over whether and to what extent the escalating climate crisis demands measures to put the brakes on driving. Germany remains the only European country without a general speed limit on its motorways. And when the authorities do impose speed limits on particular sections, drivers habitually flout them – a state of affairs for which Rosemarie Trockel’s edition might serveas photographic evidence. For “Cliché,” the artist used a speed-camera mugshot, the traffic violator’s “wanted” poster: a photograph automatically triggered by radar when a vehicle’s speed exceeds a certain limit. The device’s action is recognizable to the driver thanks to the dull red flash it generates. For her fifth edition for TEXTE ZUR KUNST, Trockel has enlarged the face of the young woman driver with the absent-minded expression, undercutting the stated purpose of this kind of depiction: the identification of the offender. She appears almost depersonalized, a blurry projection-screen-image rather than a particular individual. It is not the first time that this woman, here putting in an almost spectral appearance, has featured in Trockel’s work. The unintentional model in “Cliché” posed for “Homesick” in 2017, sporting an earring adorned with Hannah Arendt’s likeness; insiders may recognize her as the daughter of Trockel’s friend and longstanding gallerist Monika Sprüth. That earlier photograph was reminiscent of, though in lateral inversion to, Johannes Vermeer’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring” (around 1665); in light of the imaging process described above, the associations that come with this edition have a less august art historical pedigree. In its formulaic quality, it may remind some readers of the profoundly pleasurable dopamine rush that comes with driving fast – and of the sobering government sanctions that may well follow.