“ALL POLITICAL STRUGGLE MUST RELY UPON THE WORK ON THE SELF” A Conversation between Cynthia Fleury and Isabelle Graw

Cynthia Fleury, 2020

ISABELLE GRAW: In your book Here Lies Bitterness: Healing from Resentment (2023), you define resentment as a “weakness of the soul” that results in an “incapacity to act.” But you don’t merely see this affect in others, as Joseph Vogl does in Capital and Ressentiment: A Brief Theory of the Present (2022). Quite the contrary: you underline how we are all at times overcome by feelings of resentment, and you also point to the objective social reasons – such as a lack of acknowledgment and recognition – that make such bitterness seem justified. In the beginning of your book, you argue that in order to overcome resentment, it is necessary to tolerate uncertainty and injustice. While tolerating uncertainty is of course helpful, I wonder whether one should really tolerate *injustice*. Wouldn’t it be more helpful – also as a way of overcoming resentment – to politically fight against it?

CYNTHIA FLEURY: It’s not at all about separating the two but rather about understanding that to fight against injustice without succumbing to radical violence requires a measure of psychic “tolerance” of that very injustice – otherwise you plunge automatically into terror. However, individuals all too often oppose the political fight against injustice with the psychic tolerance of injustice that protects us from descending into a psychic radicality. Without the latter, we would be exposed too readily to an emotional cleavage, and the evoked non-empathy would likely transform any victim into an executioner. The book’s proposition is not to obliterate political struggle with work on the self but to comprehend that all political struggle, if it isn’t to descend into reactionary action, must necessarily rely on work on the self. This is the sense in which all analytical work is political, since it helps us pursue collective struggles more effectively. Politics must remain a process of sublimating violence and not merely another – legalist – term for arbitrary violence.

GRAW: As a way of overcoming resentment, you propose that one should stop complaining constantly and take responsibility for one’s own situation instead. Doesn’t this call for taking responsibility for oneself come dangerously close to the neoliberal insistence on self-responsibility? While it is of course important to stop seeing mistakes only in others and to acknowledge how one might have contributed to one’s own misery, I wonder whether the structural reasons for people’s bitterness get somewhat downplayed in your book. What’s more, couldn’t one consider the act of complaining as a creative way of dealing with one’s resentment? I am thinking of constantly complaining writers like Thomas Bernhard in this respect.

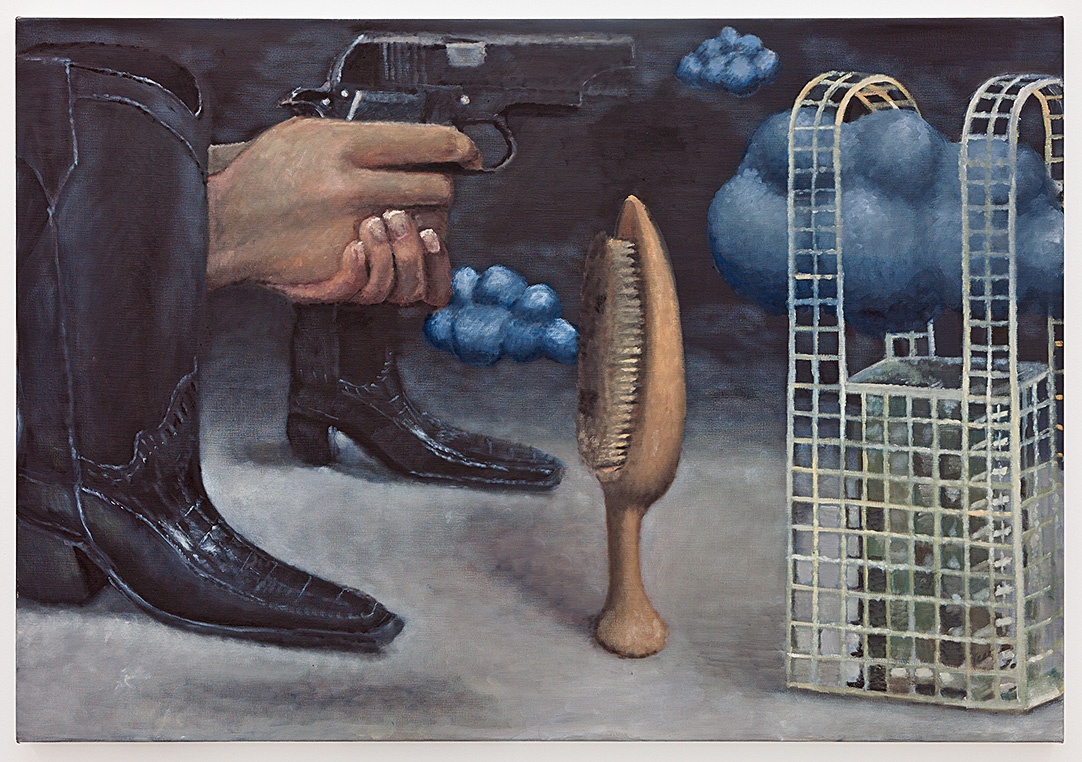

Issy Wood, “All the rage 1,” 2019

FLEURY: The complaint-as-style of Thomas Bernhard is unlike any other, which would only produce itself; it constitutes “the work.” In the book, I am constantly recalling the way writers, or indeed artists, have “sublimated” their suffering, their complaints, and their pain into creative work. The suffering that runs through the lives of individuals is in no way minimized – such as the injustices and persistence of socioeconomic determination. The question is: How do we fight these things as effectively as possible? If you make the claim that resentment is a motor of history, which it is, I would just remind you of this: resentment is not a progressive motor of history. It produces terror, the hatred of others, vengeance, and all of this under the acceptable rubric of “justice.” It’s the sublimation of resentment that produces social justice for all. On the other hand, it is unfortunately also true that those injustices are taken as the perfect excuse for decompensating resentment. Elsewhere in the book, I argue that we must firmly hold on to the Möbius strip linking the principle of individuation (which is not to be likened to individualism) with the consolidation of the state of social rights – or in other words, the ceaseless work of public policy against socioeconomic inequalities. But what must be understood at the end of the day, and what is certainly unpleasant to consider, or at least uncomfortable, is that resentment remains a deficit of symbolization and not a psychic or political translation of suffering. Otherwise, it would in fact be perfectly legitimate and desirable. Yet, clinical analysis demonstrates the extent to which resentment is harmful for the subject, even before it becomes detrimental to the community.

GRAW: You also point to how resentments decrease our potential to act and to be creative. It seems to me that “creativity” and “sublimation” function as counter-terms to resentment in your theory. You suggest that “aesthetic experience” (in the sense of an experience one makes while being creative) could be a possible way out of resentment. Could you elaborate more precisely on your understanding of both creativity and sublimation? You refer to Theodor W. Adorno, who, according to you, used writing as an act of resistance against resentment. How can creativity and sublimation lead us out of feelings of resentment?

FLEURY: The only way to elude resentment, though it can take a long time and it’s not impossible for it to catch up with you again, is to tie the power of action to the aesthetic function. Put differently, to find any form of power in action by being the one to orient action aesthetically. Or to put this differently once again, to be the one to provide its meaning, its resonance. You have to find the way to be able to create a subject, to be the agent of your life. While it is not always possible to remove yourself from socioeconomic determination or unjust situations, it is always possible to do so symbolically. Once again, it is in no way about stating that you have to give up on the fight but about understanding that we must conduct more effective political struggles, in the sense of them being more just and practiced in solidarity, thus reinforcing our capacities for sublimation and symbolization. Then it becomes possible to do anything: speak, write, love, etc. All of this helps us to become agents capable of transforming the world and our personhood.

Klara Lidén, “Paralyzed,” 2003

GRAW: You suggest that resentment diminishes our capacity to judge and differentiate. Once we are overcome by resentment, our critical capabilities rot. I wonder if one couldn’t claim the opposite in view of critical theorists like Theodor W. Adorno or Karl Marx: they both certainly resented capitalism, and each produced a brilliant analysis of its functioning. Adorno, for instance, loathed the cultural industry and wrote a still interesting (and quite disputed) chapter on it with Max Horkheimer in Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947; English translation 1972). So, couldn’t one argue in light of these writers that judgment can get heightened and sharpened by resentment?

FLEURY: Indeed, it’s always a matter of degree. Ultimately, resentment does not produce, but it ruminates, repeats its pattern, its symptom. Here again, we have an idealized and somewhat romantic vision of resentment and of violence. No, it wasn’t resentment that allowed Adorno to write, but its sublimation. In order to describe the world’s variety, its complexity, it is necessary to activate its cognitive and aesthetic functions. However, resentment will weaken these because it ultimately devalues, flattens, disregards, and denigrates everything. The world’s diversity no longer nourishes you. Of course, we have the “artists” who are at the limit of style and of “delirium.” Every work of art produces a fiction, insofar as it is able to accommodate others, be shared, and make sense for all. But not every delirium is a work.

GRAW: You also propose that democracy, with its promise of equality, leads toward resentment because it fosters the illusion that one is entitled to have what others seem to have. So, in a democratic system, there is no way around resentment because it continuously confronts us with concrete inequalities while promising equality at the same time. With this in mind, you argue that politics should establish conditions that do not strengthen resentment but that allow most people to engage in the world through their libido. What exactly do you mean by that? And why do you only want the libido to be lived out, considering that life instincts (Lebenstriebe) coexist with the death drive (Todestrieb) in our psychic life, at least according to Sigmund Freud? Isn’t the death drive – meaning aggressive and destructive impulses – also a motor of creativity and sublimation? If so, how would this enter your theory?

FLEURY: We are mortal beings, so for this reason we are necessarily structurally modeled by the conflict between the life and death drives. It is by resisting the death drive that we sublimate or rather simply exceed the instinct in order to create. Living without creating artistically is entirely possible, but not sublimating one’s finitude endangers the individual, because they can succumb to the death drive inherent in each of us. The notion of sublimation is fortunately very plastic. Without becoming aware of the death drive, we would be less inclined toward sublimation and to create. So, it’s certain that artists are more specifically individuals who have a more sophisticated awareness of the death drive and not just people with narcissistic disorders, as we are sometimes wont to believe. Nobody can resist the death drive’s deployment: a person will either self-mutilate, commit suicide, or split the self, or they may destroy others. In any case, the human being will ultimately die, and the only immortality is that of the person’s work, be that artistic or more trivially “human” in the sense of procreating, passing something on, etc.

Francisco Goya, “El Balancin,” 1791–92

GRAW: I wonder whether the cure that you propose against resentment – therapy and sublimation in the form of creative work – is available only to those happy few who are financially well off and culturally privileged. Because not everyone has access to therapy and not everyone can create an oeuvre, which you present as a way out of feeling imprisoned by resentments. Would you agree that your proposals are addressed to the creative class?

FLEURY: The class struggle is a social fact and not an ontological one. The entirety of political work consists in providing the conditions of non-alienation precisely so that the subject can have agency in life. It is clear that an individual in the painful throes of alienation – of the “colonization of being,” as Frantz Fanon wrote – will be much less able to produce a work of sublimation. But for all that, it’s in no way impossible, and it is my work as a clinician to see to the rehabilitation of this power in every single patient. I don’t know what kind of doctor I would be if I were to maintain from the outset that this were not possible. I totally understand your objection; however, it also relates to the epigraph of my book:

This book is based on a decision, a commitment, an axiom: its intangible principle or regulating idea is that man, the subject, the patient, has the power to act. It is not a question of wishful thinking, or of taking a falsely optimistic view of people. It is a question of a moral and intellectual choice – a wager that we are capable of acting. It is above all a way of insisting on the respect due to those who are in treatment, for the patient is an agent – the agent par excellence. Thinking about patients responsibly means accepting their capacity to leave denial behind in order to confront reality. Life, even in its banal routines, affirms this capacity even as it sometimes contradicts it. As for my own life, I ceased long ago to entrust it to facts alone. Battling resentment teaches us that a certain tolerance for uncertainty and injustice is necessary. What we find on the other side of this confrontation is the possibility of expanding ourselves. [1]

Translation of Cynthia Fleury: Miriam Stoney

Cynthia Fleury is a professor of Humanities and Health at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, associate professor at the École des Mines (Université PSL) and holds the Chair of Philosophy at the GHU Paris Psychiatrie & Neurosciences. Her research focuses on the tools of democratic regulation and the principle of individuation in the context of a social state governed by the rule of law.

Isabelle Graw is the cofounder and publisher of TEXTE ZUR KUNST and teaches art history and theory at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste – Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. Her most recent publications include In Another World: Notes, 2014–2017 (Sternberg Press, 2020), Three Cases of Value Reflection: Ponge, Whitten, Banksy (Sternberg Press, 2021), and On the Benefits of Friendship (Sternberg Press, 2023); and the forthcoming Fear and Money. A Novel (Sternberg/MIT Press, 2025).

Image credits: 1. © Francesca Mantovani / Editions Gallimard; 2. © Issy Wood, courtesy of the artist, Carlos/Ishikawa, London and Michael Werner Gallery, New York; 3. Courtesy of Klara Lidén, Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York, and Galerie Neu, Berlin; 4. Public domain, photo Philadelphia Museum of Art

Note

| [1] | Cynthia Fleury, Here Lies Bitterness: Healing from Resentment (Cambridge: Piloty Press, 2023), viii. |