COUNTER-SUBLIMATION On Jelena Jureša’s “Aphasia” (with Audre Lorde and María Lugones)

Jelena Jureša, “Aphasia (Act Three),” 2019

In Aphasia (2019), the artist Jelena Jureša grapples with three “cultures of violence”: the Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren), whose collection of dioramas and taxidermy mounts goes back to Belgian colonialism and reproduces its colonial gaze; [1] Austrian Heimatfilm, a cinematic genre that conveys a glorified image of nationalism after the end of the Second World War by way of looking at the country’s past during the Hapsburgian empire; [2] and the club culture that sprang up in Belgrade during the Yugoslav Wars. The chapters of the film essay spotlight connections between the histories of the countries in question, but what interests Jureša above all is the disturbingly close association between physical violence and various kinds of “cultural achievement” that arose from and alongside it. [3] To put it in Freudian terms, those achievements are cultural and artistic forms of sublimation that, far from transforming aggression and violence, in particular, facilitate them by disguising or romanticizing them. The three chapters work through the complex issues in a variety of ways, relying on newly filmed or documentary material and operating with different soundtracks: a voice-over in the first chapter, music and documentary sounds in the second, and the filmed character’s voice as well as live electronic music recorded during the filmed dance performance in the third. [4] The final and longest part is also shown by itself under the title Aphasia (Act Three): “A Kid from the Neighbourhood.” [5]

Jelena Jureša, “Aphasia,” 2019

THE VIOLENCE OF THE NEIGHBORHOOD

In this third act, Jureša zooms in on one protagonist, Srđan Golubović, to study the violence of the Yugoslav Wars and how it relates to the Serbian cultural scene. A member of the Serbian paramilitary militia known as Arkan’s Tigers, Golubović drew attention when a photograph came to light that shows him about to kick the head of a dead Muslim woman, Ajša Šabanović. The photograph was taken by the US war reporter Ron Haviv during an early massacre against the Bosnian population in Bijeljina, in April 1992, and later served as evidence when the war crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia were tried before the International Criminal Tribunal in The Hague. Golubović was identified in the photograph but has not been convicted of any crimes. Rather, since the war, he has been a celebrated trance DJ in Belgrade’s club scene.

“A Kid from the Neighbourhood” opens with documentary video footage from the trial of Slobodan Milošević, during which the photograph was first entered into evidence, followed by an extended monologue by the Croatian investigative journalist Barbara Matejčić, who recognized the man from the well-known wartime photograph when she met DJ Max at a club in 2017. She recounts his gig at the club with painstaking precision and briefly discusses conversations about his identity with others who were there that night. She then describes the scene in the photograph (which is never shown in the film) in great detail and supplies facts that the picture itself does not reveal: who can be seen in it, what exactly happened in Bijeljina, and which perpetrators of war crimes ever faced trial. [6] Not one member of Arkan’s Tigers has been convicted. DJ Max received money from the Serbian secret police until 1995 (which is to say that when he was a member of the militia, he was on the payroll of the Serbian government); in 2012, he was tried for possession of drugs and firearms but acquitted. [7]

The journalist rounds out her account of the war years and the period that followed by panning from the events in Bijeljina to the Serbian music scene. Its two defining tendencies were the nationalist turbo-folk listened to by supporters of Slobodan Milošević and, on the other side, an urban club culture spawned by a blend of escapism and resistance to the war, and which continued to flourish after the war ended. [8] The story of trance DJ Max, who was both a member of Milošević’s Arkan’s Tigers and a pioneer of the nascent electronic music scene, shows how permeable the front line between these two ostensibly opposed camps was. Max, the viewers learn, was also the name Golubović used as a member of Arkan’s Tigers. As Matejčić found out in interviews with sources, many in the club scene were aware of his past but did not take particular exception to it, since they were busy building a new subculture in Serbia, which was under sanctions at the time. In the only interview with DJ Max that she was able to find online, he calls himself a “nice guy from the neighborhood” and says that, if he were sentenced to death and permitted a single phone call, he would call his mother. His involvement in the war remains unmentioned.

“Jelena Jureša: Aphasia,” Argos Centre for Audiovisual Arts, Brussels, 2019

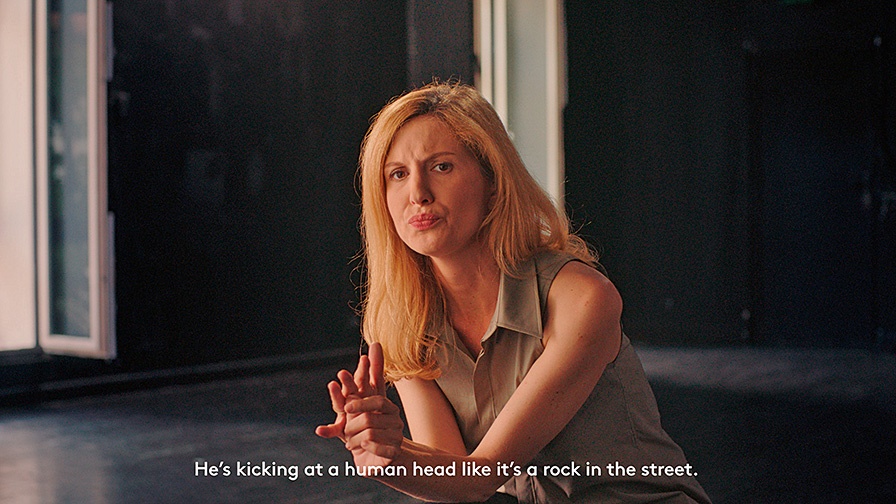

The journalist is filmed seated in a slightly angled medium shot, but she repeatedly gazes directly into the camera. Matejčić recounts how she finally comes face-to-face with DJ Max, and how he kindly helps her to find a cab, all the while she has the impression that he is well aware that she knows his past. That is where the long sequence, recorded in a single take, ends. Music comes on, and Matejčić appears in a brief close-up as she pins up her hair. Then the second part of the act begins with choreography by the dancer Ivana Jozić, who is dressed like the journalist and wears her hair in the same style.

TRAUMATIC EMBODIMENTS

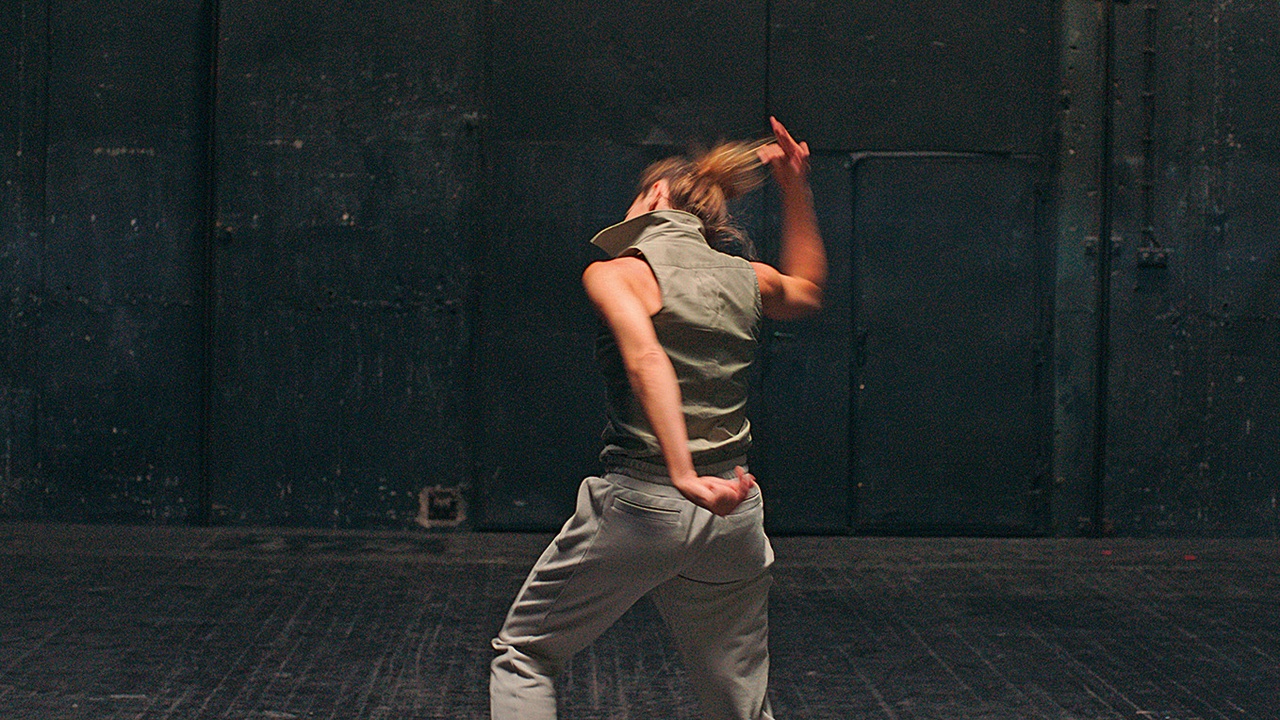

Whereas the camera is fixed in the Matejčić segment, the sequence featuring Jozić is filmed with a moving camera and contains several cuts. Jozić, too, engages with the history of violence, but physically, by mimicking gestures made by the DJ or seen in the photograph and by pantomiming clubbers’ movements as well as brutal sexual motions, a possible reference to wartime rape. Alen and Nenad Sinkauz’s experimental electronic music is heard throughout the sequence; echoes of turbo-folk and trance techno repeatedly rise and subside again, alternating with less agitated passages. The music and the choreography were created in a dialogue between the media: sometimes, the dancer is moved by the music; at other times, the music responds to her movements. Jozić can also be seen walking toward the musicians performing live; on one occasion, she even interrupts them. At the end of the third act, Max is shown DJing in a short sequence that was recorded by the journalist on her cell phone and that shows him while the soundtrack by Alen and Nenad Sinkauz is still playing.

Beginning right after Matejčić mentions her conversation with the DJ, the choreography initially appears to be an enactment of an imagined reaction, as the composed journalist’s outburst of rage. Yet the dancer’s movements and poses weave in gestures and details from the descriptions of Golubović as DJ Max and as one of Arkan’s Tigers – the upturned collar, the fingers holding a cigarette, the kick – some of which Matejčić has already imitated in her own gestures. And Matejčić is not actually quite so composed either; her facial expressions and gestures shift between different registers: a soft smile elicited by some memories gives way to stern gazes, lips signaling disdain, and tense gesticulation conveying her rage and indignation.

In an interesting way, the interrelation between the two characters is hard to pin down, since it is not readily apparent from the outset that the journalist and the dancer are different people. Still, the choreography is certainly not the monologue’s desublimated flip side, the unfiltered expression of negative affects. Rather, both sequences may be seen as manifestations of one and the same process, which consists in both a discursive and an affective-bodily engagement with the wartime events and their afterlife.

Jelena Jureša, “Aphasia (Act Three),” 2019

Both the monologue and the choreography bring to mind the dreams of soldiers suffering from combat neurosis that Sigmund Freud describes in Beyond the Pleasure Principle and that lead him to hypothesize the existence of a death drive: dreams that keep reproducing the traumatic scenes and instants that exceeded the soldier’s psychic capacity. [9] Similarly, the women reiterate the incomprehensible violence that occurred in Bijeljina and the indifference they encountered at the club in Belgrade in an effort to counter it, to avoid being paralyzed by it. In both instances – in Freud as in the film – the repetition is not identical; its point is to allow for something new to emerge.

THE WAYS OF FEMINIST ANGER

In “The Uses of Anger,” Audre Lorde draws a crucial distinction between hatred and anger. The object of hatred is the destruction and symbolic or real death of the other; anger, by contrast, aims to change the ill that prompted it by addressing the other, confronting them. “Anger is loaded with information and energy”: that energy infused with knowledge – the knowledge that the violence that has been inflicted is wrongful but also that there is an alternative to it – is the source of its transformative power. [10] With reference to Lorde, María Lugones speaks of a “second-order anger” that responds to the raging violence of the oppressors and refuses to continue as usual. [11] Hence Lugones’s characterization of it as an “inward motion intent on sense making […] neither really different nor separate from the passion of metamorphosis,” as a movement and transition, which might not be fully intelligible to an outside observer. [12] The women in Jureša’s film are in the process of transforming hatred into anger. [13] They enter into the perpetrators’ hatred and club culture’s indifference and mimetically assimilate them, only to eventually “divert” them into a different energy of repudiation. “Diversion” is how Freud describes the work of sublimation, which consists in redirecting not only sexual but also aggressive drives toward new objects; rather than attaining their immediate fulfilment, they are transformed into cultural or creative productions. But Jureša’s scenes function yet differently, representing responses to an already existing work of sublimation: to the nationalist folk music around Arkan’s Tigers and to an electronic trance music in which violence, far from being transformed, is transfigured or disguised. Unlike the club scene, these female figures do not simply dissociate the violence in an act of indifference but instead confront themselves with it and with what it triggers in them. This confrontation occurs when the women, in recalling the violence rather than maintaining the veil of silence, repeat it; passing through its scenes, though, they do not descend into the same aggression, instead diverting their negative affects into anger.

Jelena Jureša, “Aphasia (Act Three),” 2019

DIALECTICS

What the two sequences and the film essay perform is not a catharsis, a purification of negative affects, but a transformation of those affects through witnessing. [14] The film, then, presents an aesthetic that does not operate like turbo-folk, which transfigures nationalist ambitions and prods people to act on them, including beyond the confines of art; nor does it correspond to Belgrade’s club culture, which employs aesthetic means to temporarily distance or disguise violence and cruelty. Faced with these two “cultures of violence,” nationalist agitation and an ostensibly pacified subculture, each of which in its own way provides an outlet for aggressive and destructive drives, the film enacts a counter-sublimation.

The (aesthetic) representation in Jureša’s work not only bears witness to the nexus between violence and indifference; it also subjects the transfiguring and disguising forms of that violence and indifference to transformation. This process requires and generates a different energy, the energy of anger, which is distinct from hatred or indifference in that it is “loaded with information.” The characters do not intend to punish or scandalize; rather, they try to find an articulation that breaks the collective silence. In their anger, death drives (in this instance, violence and aggression) and life instincts (in this instance, artistic expression) are no longer lived out separately and sublimated in an effort to counterbalance each other’s excesses after the fact.

Counter-sublimation is not dualistic but dialectical – compare Theodor W. Adorno’s conception of aesthetic sublimation: it is mimesis to society and its suffering, which is affectively transformed by aesthetic and cognitive elements. [15] Unlike in Adorno, the aesthetic of the film is not just enigmatic but also angry, actively urging change and affecting the viewers accordingly. Just as anger, to Lorde and Lugones, indicates the beginning of a change that must gradually unfold and is necessarily open-ended, here, too, it is an informed energy in which eventually also different and idiosyncratic movements gradually start to materialize in not always altogether transparent ways.

Jelena Jureša, “Aphasia (Act Three),” 2019

The transformative power of anger springs from the act of speaking and reenacting a history of violence that has been silenced or acquiesced to with indifference. This becomes especially palpable in the choreographic sequence: the dancer’s intense performance articulates the close association between dance movements from the club, gestures from the war, and male poses of dominance, but she also disrupts this intensity herself – for instance, by stopping the music (it takes her two attempts to do so), which, rather than simply resuming, comes back on a different note. When the music stops, the character, too, steps outside the mimesis and the representation of violence. She pauses. One can hear her breathe and softly cough. Her movements after that instant, again, are not pure imitations of the men; she also deconstructs or disarticulates their gestures, sometimes with an edge of the grotesque. Performing the motions of sex, Jozić steps back, audibly groans, then screams in anger. One sees her with a cigarette in her hand, like the DJ, but her gestures also contain her grief. Her anger thus gradually charts a latitude beyond the mimetic exposure of disguised, complex histories – a latitude, however momentary and fragmentary, for other gestures that, amid the fierce reiterations, signally also accommodate the more fragile facets of her corporeality.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Francesca Raimondi is a deputy professor of theoretical philosophy specializing in aesthetics at the Freie Universität Berlin. She lives in Berlin and Amsterdam.

Image credit: all images courtesy of Jelena Jureša

Notes

| [1] | In light of the fraught history of its genesis, the museum was closed in the 2010s for extensive modernization; its colonial past is now explicitly addressed in its displays. The footage recorded by Jureša that constitutes the bulk of the first part of Aphasia dates from when the museum was closed and the exhibits were put into storage or wrapped up for protection. The sequence is accompanied by a theatrical voice-over that discusses the dioramas, Belgium’s colonial past, and today’s visitors, among other subjects. The colonial dioramas and mounted animals remain on view after the modernization. |

| [2] | The second part is composed entirely of documentary material, which is arranged in associative fashion. It delves into the filmed racist experiments conducted during the First World War by the physician Rudolf Pöch and during the Second World War by his former assistant, as well as into the life of the United Nations secretary general and president of Austria Kurt Waldheim, whose complicity with Nazi war crimes while serving as an officer of the Wehrmacht was uncovered decades later. |

| [3] | Sigmund Freud, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. and ed. James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1953), 7:178. Freud first introduces his concept of sublimation in this early work. |

| [4] | The film’s soundtrack was produced by the Croatian composers and performers Alen and Nenad Sinkauz. |

| [5] | Aphasia has been screened on several occasions, including in 2022 at Manifesta 14, Prishtina, curated by Catherine Nichols, and in 2024, together with Jureša’s Don’t Take It Personally, in dialogue with works by Aernout Mik, in the exhibition “Run-Through” at De Garage, Mechelen, curated by Andrea Cinel. |

| [6] | Matejčić also dwells on the picture’s media history; it has been widely used by journalists to illustrate “the hell of war,” Susan Sontag wrote about it, and Jean-Luc Godard used it in a short film. She knows that Srđan Golubović actually kicked Ajša Šabanović from a conversation with the photographer; other eyewitness accounts are her sources for further background information on the photograph. |

| [7] | At the time, his story was most prominently reported in the media by Boris Dežulović, “Skrivena kamera u Bijeljini 1992,” Peščanik, September 14, 2012. In November 2022, Rolling Stone ran a sensationalist investigative report by Sophia Jones, Nidžara Ahmetašević, and Milivoje Pantović, “The DJ and the War Crimes,” which does not mention Dežulović’s article, Matejčić’s research, or Jureša’s film. |

| [8] | Its most prominent figure, the singer Ceca, married Željko “Arkan” Ražnatović in 1995. |

| [9] | See Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, in The Standard Edition (London: Hogarth Press, 1955), 18:12–14, 31–33. |

| [10] | Audre Lorde, “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), 127. |

| [11] | Lorde and Lugones discuss the role of anger primarily in the context of anti-racism (also present in feminism) and homophobia. Although there are clear differences, their reflections seem important to me for a feminist perspective on the oppressive features of patriarchal nationalism and its culture of indifference as well. |

| [12] | María Lugones, “Hard-to-Handle Anger,” in Pilgrimages / Peregrinajes: Theorizing Coalition against Multiple Oppressions (London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2003), 103–20, at 103–4. For the emancipatory and progressive meaning of feminist anger in Lorde and Lugones, see also Federica Gregoratto, “Between Anger and Hope: Emotions in Progress,” in “Therapy and Conflict: Between Pragmatism and Psychoanalysis,” themed issue, European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy 15, no. 2 (2023): 1–18. |

| [13] | Lugones goes on to draw a distinction between different forms of “second-order anger” that one might apply to the description of Jureša’s film: “There is anger that is a transformation of fear; explosive anger that pushes or recognizes the limits of one’s possibilities in resistance to oppression; controlled anger that is measured because of one’s intent to communicate within the official world of sense; anger addressed to one’s peers in resistance.” Lugones, “Hard-to-Handle Anger,” 103. |

| [14] | The catharsis hypothesis figured prominently in early psychoanalysis because of Josef Breuer’s work; Freud gradually disavowed it, replacing it with free association. To my mind, the work of psychoanalysis on this point implicitly acknowledges that the aggressive drives Freud discerns in early 20th-century society – a society defined by capitalism, the experience of war, the patriarchal family, etc. – are irreducible, but it also argues that they may be transformed. Meanwhile, the female characters in Jureša’s film undergo a process of a type not found in Freud: a verbal and gestural working-through of cultural forms that are in themselves already products of sublimation and revealed to be violent or enabling violence. |

| [15] | See Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, ed. Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (London: Continuum, 1997), 23. |