THE DEATH DRIVE AS AN EMBLEM OF MODERNITY

SpaceX mannequin in Elon Musk’s Tesla Roadster, 2018

It would be hard to find a precarious social phenomenon that has not already been explained, or better explained away, by the death drive. The fascination inspired by the concept goes far beyond the psychosocial aggressive tendencies of individuals – the homicidal instinct, for example, often invoked by mainstream cinema. It entices us to summarize the social miseries of the present day, in all their crisis-ridden or catastrophic proportions, under this rubric. And it would indeed be tempting to pinpoint a unifying principle underlying such diverse phenomena as the ubiquitous mobilization of hatred in today’s media, the self-destructive tendencies directed against the natural realities of life, the propensity for discrimination and exploitation, but also “moral rigor,” and, finally, that highest measure of all destructiveness, war itself. Such a principle would make the question of evil, which a secular society can no longer personify in nor delegate to the figure of the devil, seem answerable –namely, as an integral constituent of human existence. From this point, however, it is not far to a radical anthropological pessimism that would nevertheless enlist itself in the project of its own critical or “healing” analysis. [1]

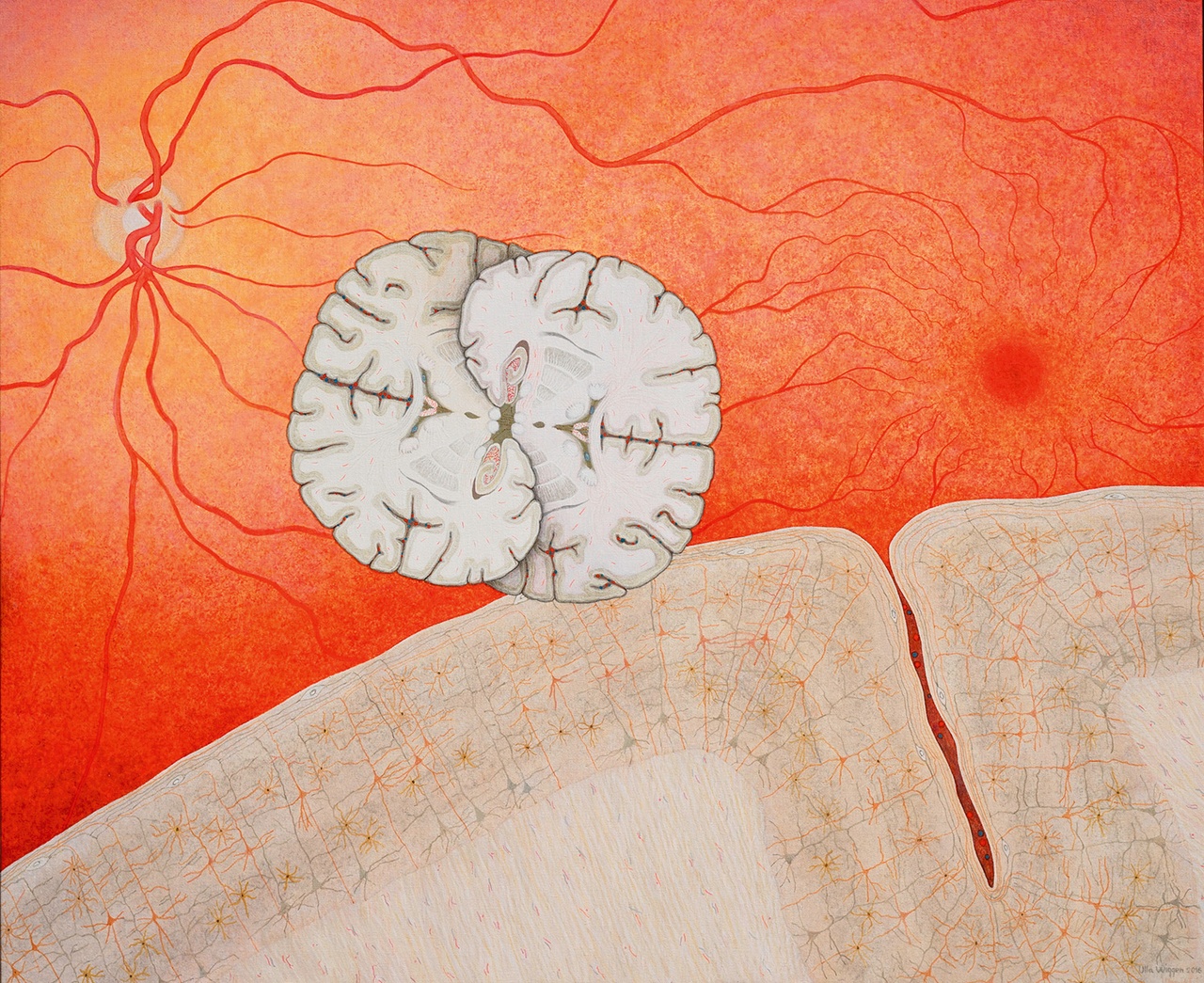

Ulla Wiggen, “Passage,” 2016

For if the concept of the death drive is interpreted literally, it becomes a biologistic banality, yet if it is deconstructed into an anti-essentialist notion and interpreted within a broader field of references, it runs the risk of losing its specificity and thus its meaning. But how can we understand the death drive without forcing it into such a hopeless double bind between essentialism and anti-essentialism? This would require not starting with the question of whether it actually exists but, more importantly, considering what the concept offers and how the problem of its positive determinability can be appropriately addressed. As is well known, Sigmund Freud, taking up a proposal by Sabina Spielrein, positioned the death drive as the dark adversary of the life drives in a new formulation of his dualistic drive theory in 1920. Clinical insights based on the repetition compulsion he observed in traumatic (war) neuroses led him to question the regimen of the pleasure principle and to transform his original placement of the libido in opposition to the ego (or self-preservation) drive into a new, more fundamental polarity of constructive and destructive forces as he saw them at work in cell biology, for example. Two assumptions are key to the postulation of a negative principle in life itself: first, the idea of a “need to restore an earlier state of things” [2] that is embodied in the death drive; and second, the constitutive “unobtrusiveness” of the death drive, whereby it only becomes tangible when it is fused with the life drives – for example, as sadism or masochism. It didn’t take long, however, before Freud applied these clinical analyses and metapsychological assumptions to the generation of interpretive models of cultural theory, in an attempt to root phenomena such as war and the fate of humanity as a whole in the interplay of Eros and Thanatos. [3] In order to do so, he had to presume the shift of the death drive from an inner return to the inorganic to an outwardly directed destructiveness toward others, and here, as in all of his writings on cultural theory, he gets stuck in the anthropological short circuit between phylogenesis and ontogenesis.

And although in 1915 Freud was still calling for a discussion of “Thoughts for the Times on War and Death,” his theory of the death drive – like the drive theory as a whole – lacked a grounding in the specific historical and social conditions that give every form of destructiveness its specific shape in the first place. [4] In a certain sense, one could say that Freud’s cultural theory resists the historical nature of death and war. [5] It doesn’t provide answers to questions about structural or impersonal power, [6] and with it vanishes the concept’s usefulness for grasping the uniquely modern relations of violence, such as the “primitive accumulation” that Karl Marx spoke of as the epitome of the early modern excesses of violence that inaugurated capitalism but also the revolutionary mass mobilization and the resulting popular and liberation struggles, the industrialization of war machinery, and the mass exterminations of colonialism and National Socialism.

Female munitions workers, Nottinghamshire, 1917

So, is there anything in Melanie Klein’s and Jacques Lacan’s essentialist or anti-essentialist reformulations of the concept that could serve as a basis for such an attempt to use the death drive to explain the uniquely modern conditions of violence? Unlikely in Klein’s work, since she largely refrains from speculating on cultural theory. And yet, she does propose the ego as the theater of a war between love and hate, those emotions deeply rooted in the antagonisms of the drives, and thereby postulates, at least indirectly, their modernity. [7] With Klein, the death drive is undoubtedly less unobtrusive than with Freud; [8] it has a powerful and constant presence in The Psychic Life of the Child, and yet, following the “depressive position,” there remains, at least within certain limits, the therapeutic possibility of directing the death drive into constructive channels – “moderated and tamed, and, as it were, inhibited in its aim.” [9] With Lacan, by contrast, there occurs an anti-essentialist distillation of the death drive; it is now no longer anchored in biology, but, as an element of a vectorial drive theory, in the symbolic. [10] As part of every drive, the death drive denotes the drive’s surplus or excess, precludes its gratification, and only allows it to orbit around its aim. In this sense, the death drive would be a post-metaphysical principle of pure finitude, of the absence of all meaning, and of radical evil in the Kantian sense. [11] In Freud, there is also a counterpart to the death drive: the eternal Eros. In structuralist psychoanalysis, the former is located within the latter, thereby embodying the principle of the radical futility of Eros. This means that, in strict structuralist terms, there can no longer be any hope and therefore no positively formulated therapeutic objective – only the recognition of one’s own more or less self-destructive surplus-enjoyment. Hope is certainly not the last to die here; in fact, it is always already dead – and yet what remains is not necessarily just silence.

Slavoj Žižek and Alenka Zupančič have both tried to locate another moment of inversion in the argument about the fundamental excess of the drive: Žižek by making surplus-enjoyment the epitome of neoliberal subjectivation and contrasting it with the invocation of a new master who, on behalf of the now “divine” death drive, introduces a productive split that points the way to “true unity”; Zupančič by maintaining that the death drive does not mean “wanting to die” but rather “wanting something, even if the price for it is death,” by which she merges the death drive into the concept of desire. [12] Both approaches seem interesting to me for the consistency with which they reinterpret the structuralist legacy and position it politically, and yet they also drive something decisive out of the concept of the death drive that was still intrinsic to Freud’s determinations of the conservative aims and unobtrusiveness of the drives, and which also shines through in Lacan’s formulations. In other words, Žižek’s and Zupančič’s voluntaristic appropriations sidestep the problem of the positive determination of the death drive and thus its uncanniness as an emblem or negative historical sign of modernity. [13]

Louis Malle, “Damage,” 1992

For the death drive is simply not suitable as a basic metaphysical concept from which empirical phenomena could be derived and imaginatively determined. On the contrary, such an understanding, in which essentialism and anti-essentialism seemingly align, eliminates the true challenge of the concept. This challenge would rather consist in grasping the hypothetical, indeterminate, and ultimately unconscious aspects, which are expressed in the death drive and which do not allow themselves to be made available; [14] this means accepting that there is some kind of correlation between the concept and the phenomena it refers to – violence, aggression, or war – such that the concept is always already inscribed in the conditions it is being used to describe. The vectorial conception of the drive provides at least some glimpse of this. This conception culminates in the idea that it is not the drive that drives; instead, the drive first emerges from a specific field of forces as a concept of driving, which in turn can then be related to the empirical relations of violence. In other words, it is not the drive that explains war, but conversely, it is war and modern relations of violence in general that first lead to their description in terms of the effect of the drive. Connected with this is also the recognition of the historical and social conditionality of the drive; at the same time, a moment of indeterminacy remains, because the concept becomes part of the field itself, appears as one of its protagonists, and can therefore neither metaphysically account for nor clearly define this field.

In other words, the uncanniness of the death drive lies precisely in making the excessiveness of modern relations of violence appear comprehensible to us, even though the drive only makes itself visible to us symptomatically rather than analytically. All positive determinations or explanatory figures are ultimately incapable of actually providing any such comprehension. The concept remains a constitutive part of the dynamic that it seeks to describe. Ultimately, it fails to shed light on many phenomena, especially those shifts from an inner to an outer directedness, from concealment to manifest expression, from positive to negative drive energy, from constructive to destructive forces. This is precisely what would be necessary to penetrate the different, often ambivalent positionings that modern forms of violence impose on us.

Joseph Barbera and William Hanna, “Tom and Jerry,” 1949

And yet, it seems important to me to hold on to the concept of the death drive – indeed, not as a metaphysical ground or as an empirical explanation of concrete violence, but as an indicator of a perpetual problem. [15] For as a threshold, it is the drive that marks the interface not only between soma and psyche but also between meaninglessness and meaning. The death drive marks out the void of any meaning as only it can. It is precisely in this respect that the death drive can be determined to be neither strictly positive nor strictly negative, neither strictly historical nor strictly conceptual, because even the determination of the void itself still contains a positive element. [16] This problem cannot be glossed over by adopting, with Freud, the doctrine of drives as “our mythology” and thus as a metaphysical principle; ultimately, the concept of drives can only be justified transcendentally as a condition for the possibility of speaking about the borderline phenomena of life and death, of war and culture. As we face the excesses of violence in modernity, speaking about the possibility of speaking itself will continue to gain in importance. The death drive particularly characterizes the discursive dimension of violence, a violence of speaking that seeks to silence speaking itself. Confronting this form of violence cannot succeed within a framework of either structuralist hopelessness or liberal fantasies of care and healing. Rather, it is necessary to accept the challenge posed by the two central manifestations of the death drive that we find within ourselves: the pursuit of imagined meaning as well as its assertion on behalf of the impulse to denounce.

Translation: Soliman Lawrence

Helmut Draxler is is an art historian, cultural theorist and curator; from 2014 - 2025 he taught at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. Latest publications: Was tun? Was lassen? Politik als symbolische Form (tentare, 2024), Die Wahrheit der Niederländischen Malerei. Eine Archäologie der Gegenwartskunst (Brill/Fink, 2021) and Abdrift des Wollens. Eine Theorie der Vermittlung, (Turia+Kant, 2017).

Image credits: 1. Public domain, photo SpaceX; 2. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz; 3. Public domain, photo Imperial War Museums; 4. © Moviestore Collection Ltd / Alamy; 5. © Allstar Picture Library Limited / Alamy

Notes

| [1] | This is in the sense of the “Thanatosis of Enlightenment” that Ray Brassier speaks of in relation to Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno. See Brassier, Nihil Unbound: Enlightenment and Extinction (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 32–49. |

| [2] | Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle [1920], in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. and ed. James Strachey, 24 vols. (London: Hogarth Press, 1953–1974), 18:57. See also: “Those instincts are therefore bound to give a deceptive appearance of being forces tending towards change and progress, whilst in fact they are merely seeking to reach an ancient goal by paths alike old and new. Moreover it is possible to specify this final goal of all organic striving. It would be in contradiction to the conservative nature of the instincts if the goal of life were a state of things which had never yet been attained. […] If we are to take it as a truth that knowns no exception that everything living dies for internal reasons – becomes inorganic once again– then we shall be compelled to say that ‘the aim of all life is death’ and, looking backwards, that ‘inanimate things existed before living ones’” (18:38). Hereafter, all references to Freud’s Standard Edition will be abbreviated SE, followed by volume and page number. |

| [3] | Especially in Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents [1930], in SE, 21:59–145, as well as in Freud, “Why War?” [1933], in SE, 22:197–215. |

| [4] | “Thoughts for the Times on War and Death” [1915], in SE, 14:274–300. |

| [5] | On the historicity of death, see the classic study by Philippe Ariès, The Hour of Our Death, trans. Helen Weaver (New York: Borzoi, 1981); originally published as L’Homme devant la mort (Paris: Seuil, 1977). On the historicity of war, see Bernd Hüppauf, Was ist Krieg? Zur Grundlegung einer Kulturgeschichte des Kriegs (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013). Hüppauf places particular emphasis on the emergence of the collective singular form around 1800 and the discursive and media dimensions of war associated with it. |

| [6] | Heide Gerstenberger, Impersonal Power: History and Theory of the Bourgeois State, trans. David Fernbach (Leiden: Brill, 2007). |

| [7] | See Eli Zaretsky, Political Freud: A History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), especially chapter 4: “The Ego at War: From the Death Instinct to Precarious Life.” |

| [8] | For Klein, the antagonism of drives represents the quasi-metaphysical basis of the emotional ambivalence between love and hate, which can develop from a paranoid-schizoid destructive rage to a depressive recognition of guilt and efforts to make amends. Clinically, this has been extremely productive, but it hardly permits application to the social and historical sphere. See also R. D. Hinshelwood, A Dictionary of Kleinian Thought, rev. ed. (London: Free Association Books, 1994), 266–67: “She found a way of dealing with two outstanding problems at once: solving the riddle of the early origin of the superego, and putting clinical flesh on the bones of Freud’s theory of the death instinct.” |

| [9] | Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, 21:57–146, at 21:121. In this sense, see also Kurt R. Eissler, “Death Drive, Ambivalence, and Narcissism,” The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 26 (1971): 25–78. |

| [10] | Especially in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Lacan develops his understanding of the drive as a montage or vector resulting from the four determinants of the drive: pressure, object, aim, and source. |

| [11] | In the Metaphysics of Morals from 1797, Immanuel Kant defines radical evil as a “powerful antagonist” to the categorical imperative, namely “to rationalize against those strict laws of duty and to cast doubt upon their validity.” |

| [12] | See Slavoj Žižek, “Theology, Negativity, and the Death-Drive,” XLII Sigmund Freud Lecture, Sigmund Freud Museum, Burgtheater, Vienna, May 6, 2015; YouTube video available online here. Published in a German translation as Der göttliche Todestrieb. Sigmund Freud Vorlesung 2015, trans. Sergej Seitz and Anna Wiedler (Vienna: Verlag Turia + Kant, 2016), esp. 106–7. See also Slavoj Žižek, The Parallax View (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), and Alenka Zupančič, Ethics of the Real: Kant, Lacan (London: Verso, 2000). Published in German as Das Reale einer Illusion. Kant und Lacan (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2001), 13–14 (quote only found in German edition; translation by Soliman Lawrence). Zupančič gives an extremely complex reconstruction of her understanding of the sexual character of the death drive in her detailed examination of Lacan, Gilles Deleuze, and Brassier in What Is Sex? (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017). |

| [13] | Gertrude Stein speaks of war as an emblem of modernity; see Jacqueline Rose, Why War? Psychoanalysis, Politics, and the Return to Melanie Klein (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993), 16. On the uncanniness of war, see Christoph Menke, “Kritik des Krieges,” Philosophie Magazin, no. 74 (2024): 16–21. |

| [14] | Freud’s cautious beginnings in Beyond the Pleasure Principle do more justice to this than his overt declaration of belief in Civilization and Its Discontents. |

| [15] | From a purely clinical point of view, the term seems obsolete to me. |

| [16] | Here, I am referring specifically to formulations in Lacan and Zupančič, but I wouldn’t want to speak of a purely “negative ontology,” because it seems, to me, to once again sacrifice the affirmative and thus historical moment of the death drive. |