Art history often frames the conflict between André Breton and Georges Bataille as an opposition between two artistic theories – one grounded in strategies of sublimation, the other in recognizing the generative force of artistic creation within the death drive itself. Fock takes a different approach, arguing that Bataille’s writings are shaped less by Sigmund Freud’s drive theory and more by a notion of death rooted in G. W. F. Hegel’s philosophy. Yet the artistic theory that emerged from this was by no means nihilistic. Fock illustrates its anti-bourgeois, emancipatory force through a contemporary example: P. Staff’s exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel.

In 1929, Georges Bataille became editor of the art magazine Documents. This opened an opportunity: on the magazine’s pages over the next two years and in nearly 40 articles, he sketched the contours of his theory of art, which he consistently pursued and finalized throughout the 1940s and ’50s. Its genesis is inseparable from Bataille’s enmity toward André Breton, which was rooted in the antagonism between their respective views on art. Though they may share a common starting point – the lack of unity between Spirit and Nature in external reality – it was Breton, then the most prominent spokesperson for French Surrealism, who was convinced he had found the “great key to reconciling” Spirit and Nature in verbal and graphic automatism. Bataille, on the other hand, firmly repudiated ascribing such a mediatory function to art. Art should instead turn itself irreconcilably against the Spirit given that the latter has, as a matter of principle, condemned the mediation with Nature to failure.

Bataille was never considered one of the Surrealists, and Documents did not represent a (separatist) project within the movement simply because a couple of outcast and renegade Surrealists happened to gather in the publication’s context. In its fourth issue, the illustrated essay “Figure humaine” (1929) was published, revealing the fundamental orientation of Bataille’s theory of art. From editorial assistant Michel Leiris’s perspective, the essay was akin to an “assassination attempt” on the “reassuring idea of a human Nature,” through which Bataille put art in the service of death. This refers to Bataille’s notion of an artistic process through which the discriminating determination of (human) Nature is torn down, and the life that is excluded through this determination can resist the Spirit, which has rejected it as a failure. By contrasting Bataille’s theory of art with Breton’s, I explain this process via Bataille’s corresponding art-theoretical writings and also conceive of it beyond this juxtaposition, thus illustrating that Bataille’s theory of art continues to provide a means for exploring the procedures of contemporary art.

“Figure humaine” is preceded by a posed black-and-white photograph of a petty bourgeois wedding party. Lined up in two rows before a small countryside hardware store, 26 people stand in uniform festive attire, clearly methodically organized around a bridal couple who are placed at the center. Yet in this image, Bataille sees a process at work that entails the “true negation of the existence of human Nature” – that is, the negation of what the prevailing bourgeois convention has established (human) Nature to be. The photograph should therefore be “perfectly shocking for the Spirit,” since it does not seem reconcilable with its own definition of (human) Nature.

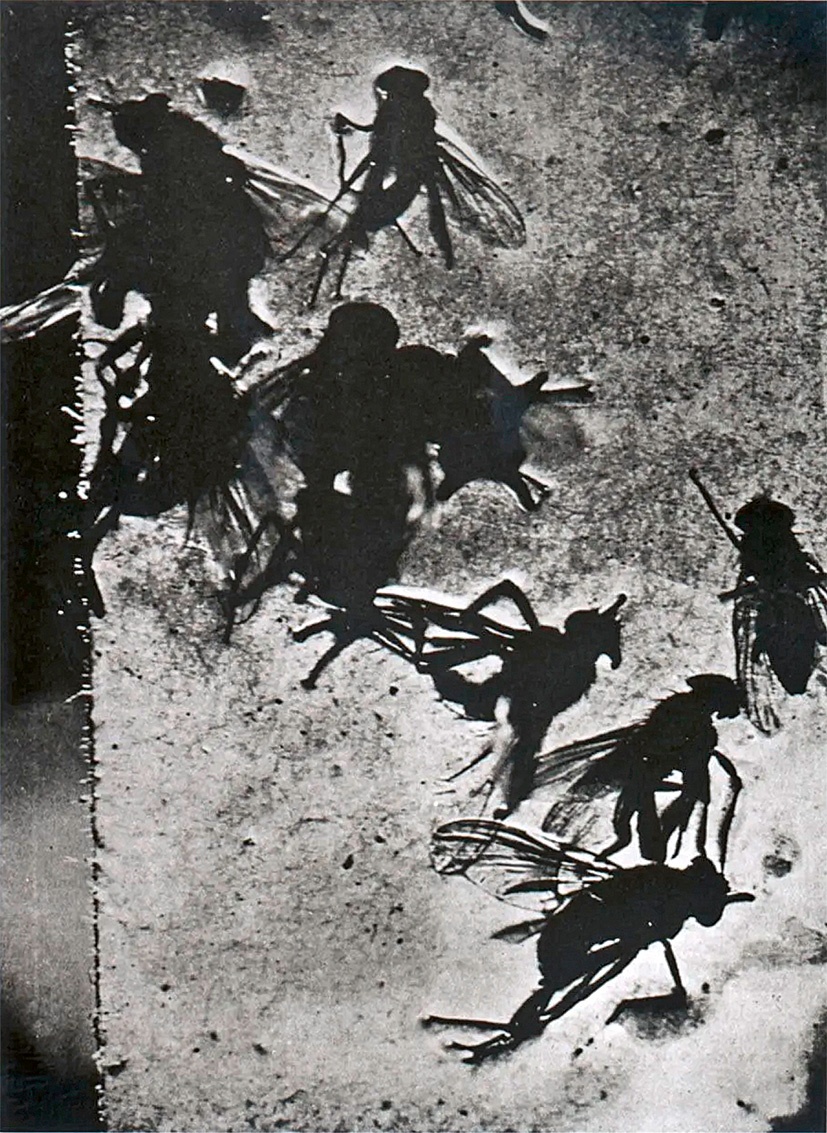

The Spirit, generally speaking, has Nature as a prerequisite. But it has also emerged historically in the form of bourgeois law, which in turn has determined its own concept of Nature as one that aims to reproduce the bourgeois-capitalist Spirit. This determination of Nature encompasses the human (in its sexuality, sexes, body, race, etc.), alongside flora and fauna, as both a part of Nature as well as part of the life of the Spirit. Anything that is not identical to this bourgeois Nature is rejected by the bourgeois Spirit as counter-natural. Demonstrating one’s identity with the bourgeois determination of Nature is, for Bataille, the actual aim of this photographic wedding documentation. Yet the staging, which betrays itself by the put-on etiquette, exposes a process that does not exemplify this determination but – against its actual intention – disfigures it. Thus, every one of these “human figures” remains on the outside of bourgeois Nature, like a “fly on the speaker’s nose.” Bataille reached the conclusion that the “presumed continuity” of this Nature, on account of the many lives it excludes, might be better substituted by a “juxtaposition of monsters.”

The process highlighted by means of an ordinary photograph in “Figure humaine” subsequently goes on to mark the contours of Bataille’s concept of art: the endeavored but ultimately failed representation of concordance with that which the bourgeois Spirit calls Nature exposes this determination to dissolution and shows the Spirit the negation of the conditions for its reproduction. Art therefore has, as he writes in another issue of Documents, “a double interest,” which is to express “a partial decomposition analogous to that of corpses and, at the same time, the transition to a perfectly heterogeneous state.” In other words, in the – intended – destruction of the bourgeois definition of Nature, the life that has been excluded as counter-natural because it is heterogeneous transitionally asserts itself against the bourgeois Spirit.

With his theory of art, the process of which he understood early on in analogy to death, Bataille distanced himself from the dominant practices of the avant-garde circles at that time. For him, their Surrealist “dreams and Cimmerian fantasies” treacherously placed the self-proclaimed rebellion against the bourgeois Spirit “under the protection of (bourgeois) laws.” These remarks were directed not least at Breton, who was not looking to destroy the imbalance between Spirit and Nature perpetuated by bourgeois law but who strove for their reconciliation through Surrealist art, that is to say, by means of fantastical methods. The prerequisite for this synthesis was a “moral asepsis” that Breton expected from those in his company – and with that, the exclusion of anything counter-natural, perverse, or ruined. This rejection had essentially already been carried out by the conventions of the bourgeoisie as guardians of the prevailing mediation between Spirit and Nature. But Breton demanded that art transform the life that was rejected by this very mediation as counter-natural into a form compatible with the bourgeois purpose of Nature. Borrowing from Sigmund Freud in a somewhat idiosyncratic way, Breton understood this kind of artistic process as “sublimation” through which the baseness of perversions and such are elevated to a higher or surreality, which he later, not coincidentally, compared to “a specific ‘sublime point’ on the mountain.” Essentially, the counter-natural life would then be acknowledged by the very same bourgeois Spirit that determined it was counter-natural in the first place – but only in sublimated form.

By contrast, when Breton writes “at length about flies” in allusion to the very exclusions he demanded, it is only “because Mr. Bataille loves flies,” he explains. His Surrealist followers, however, love “the mitre of old conjurers,” Breton continues, “on which no flies land, because we performed ablutions to chase them away.” He obviously realized that Bataille’s delineation of the aesthetic process in “Figure humaine” was meant as a critique of Surrealism and its approach to art. This prompted Breton to paint the then generally unknown Bataille as an enemy across several pages of his “Second Surrealist Manifesto” from 1929 (adding to the already-cited zingers), also as a stand-in for the Surrealist defectors in the orbit of Documents. For Breton’s allies, Bataille was as good as “executed” as a result of these gibes. In any case, in veering toward the fly-infested exterior of (human) Nature, which Breton sought to sublimate, Bataille drew “closer to the dead than to the living.”

Unlike Breton, Bataille posits that the Spirit that transgresses in order to attain (a heretofore unactualized) unity with Nature is still subject to fall into baseness. If, on the contrary, one turns to art to seek reconciliatory elevation through the abstraction of the determinations of external reality, which (re)produce the missing unity in question, then for Bataille, one might as well go “to the art dealer like one goes to the pharmacy, in search of nicely displayed remedies to disclosable illnesses.” For Bataille, the destiny awaiting the Parisian Surrealists was inevitable. Yet if art makes use of its destructive process, the prevailing Spirit can be confronted – from below – by that life that can only express itself unbroken when that Spirit ceases to be. Bataille later equated this negativity of art unequivocally with the idea of death. His conception of art can be traced back to the influence of Alexandre Kojève’s famous lectures from the years 1933 to 1939 on G. W. F. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, which taught Bataille that the concept of death also denotes an irreversible loss of a historical mediation of Spirit and Nature. This might be, for example, the overcoming of the premises on which both bourgeois law and its resulting determination of Nature are based, whereby both would no longer be reproducible thereafter. And since the subsequent mediation of Spirit and Nature following the preceding bourgeois one must be predicated on this loss and the actual “tearing out” of the Spirit from and beyond itself means the Spirit’s transitional loss of itself, this “death” also causes fear. Which is, as a rule, why most are apt to avoid it.

Bataille therefore did not consider death as a psychoanalytical death or destructive drive, to be seen as the complementary antithesis to Breton’s sublimation. On the one hand, and beyond Surrealist assumptions, he understood death as Spirit’s loss of the ability to demarcate between itself and what it defines as Nature. For Bataille, the Spirit, having become its own death, is, however, also haunted by that which it has ruined in excluding it from the determination of Nature. Death in this case is the Spirit’s “shipwreck” within its own arbitrary “abject Nature.” Art, with its corrosive negativity, can make this transition toward the Spirit’s death experienceable, if only in transition and in semblance. On the other hand, death then becomes an outlet for an aesthetic reversal. What is “external and strange” to the bourgeois mediation of Spirit and Nature and “refuses” it can, in art, be used against this Spirit, can tear down its boundary with the counter-natural that has been insulating it from the depraved life it rejects. That ostracized “failure,” the life that has been shut out, seeks to disempower the Spirit, to find a “success of failure.” Despite its many discriminating premises – androcentric, extractivist, heteronormative, colonial, racist, etc. – the bourgeois Spirit is brought to see in its own death “that it is the failure that succeeds.”

The ongoing significance of this aesthetic process for contemporary art can be found, for example, in works by P. Staff. Filmed material of animal-origin urine, sperm, meat, skins, and furs being turned into hormone and meat products shown in the video installation On Venus (2019) utilizes deformation, in part through double-exposure techniques, to emphasize once again the discord in the prevailing coexistence with Nature. Whatever in Nature – of which humankind is a part – that cannot become a precondition for the Spirit, or does not have the precondition to become Spirit, is eliminated without further ado. In this case, it is leftovers of animal lives that the industry deems unsuitable for the production of hormones or meat goods, respectively, and consequently disposes of like mere trash. With Bloodheads (Kunsthalle Basel) (2023), P. Staff, in collaboration with Basse Stittgen, uses blood from a diverse array of animals to transform discarded slaughterhouse rejects into replicas of the Kunsthalle’s architectural and design fittings. For the entire duration of the three-month “In Ekstase” exhibition, they replaced the original objects and were also exhibited in a separate room, corroding the line between the natural and the unnatural underneath an acid-yellow light. The reversal described by Bataille, wherein the rejected life turns against the very Spirit that seeks to shut it out, comes through in the eponymous work In Ekstase. Five holographic fans display a poem with verses such as “you are envious / of the air” or “crying in the street / trans sexed / cherubic boy-girl / stared down by strangers” and “maybe happy,” ending in a repeated twist: “YOU ARE DEAD / I AM ALIVE.” It is, as Bataille puts it, “ecstasy finding release from great fear” that this death makes no less, even if it is the very life that the discriminating premises of the bourgeois Spirit have rejected – and ruined – as something counter-natural. This life, able to be experienced because of a process that undermines the bourgeois determination of (human) Nature, can be extrapolated through the theory of art that Bataille initiated in “Figure humaine” – and the significance it accords death – as a failure, one that, from an irreconcilable point of view, can only be regarded as a success.

Translation: Maya Dalinsky

Nils Fock is a PhD candidate at the HfG Offenbach under Juliane Rebentisch and Christoph Menke with the thesis “Abjekte Natur. Eine Theorie der Gegenwartskunst nach Georges Bataille.”

Image credits: 1. P. Staff, courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council; 2. Public domain; 3. © P. Staff, courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council; 4. Courtesy of P. Staff and Kunsthalle Basel, photo Philipp Hänger; 5 © P. Staff, courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council

Notes