“IT’S NOT A THEMATIC, IT’S AN ACTION” A Conversation About Exhibition Politics with Zasha Colah, Ghislaine Leung, and Eric Golo Stone, Moderated by Antonia Kölbl and Felix Vogel

“Eva Barto: The Supporters,” Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, 2021

FELIX VOGEL: The first issue TEXTE ZUR KUNST published on the politics involved in exhibition-making was titled “Ausstellungspolitik.” When rereading it in preparation for this second issue on the topic, we were surprised by how many of the themes discussed in 1996 are still pressing today, some maybe even more so than then. The dubious musealization of non-Western objects in Europe and North America remains unresolved despite efforts toward restitution, for instance. Other constellations appear to have changed substantially, such as the figure of the powerful star curator as embodied by people like Hans Ulrich Obrist. But one of the 1996 issue’s core concerns has since gained in importance to a degree unimaginable back then, at least from a German perspective: the extent to which private entities, be they mega-galleries or collectors, exert financial influence over public institutions. In light of these power shifts, we want to open the conversation by asking: How do you negotiate the conflicts between commercial and noncommercial interests as well as your own critical standards when you work on exhibition projects?

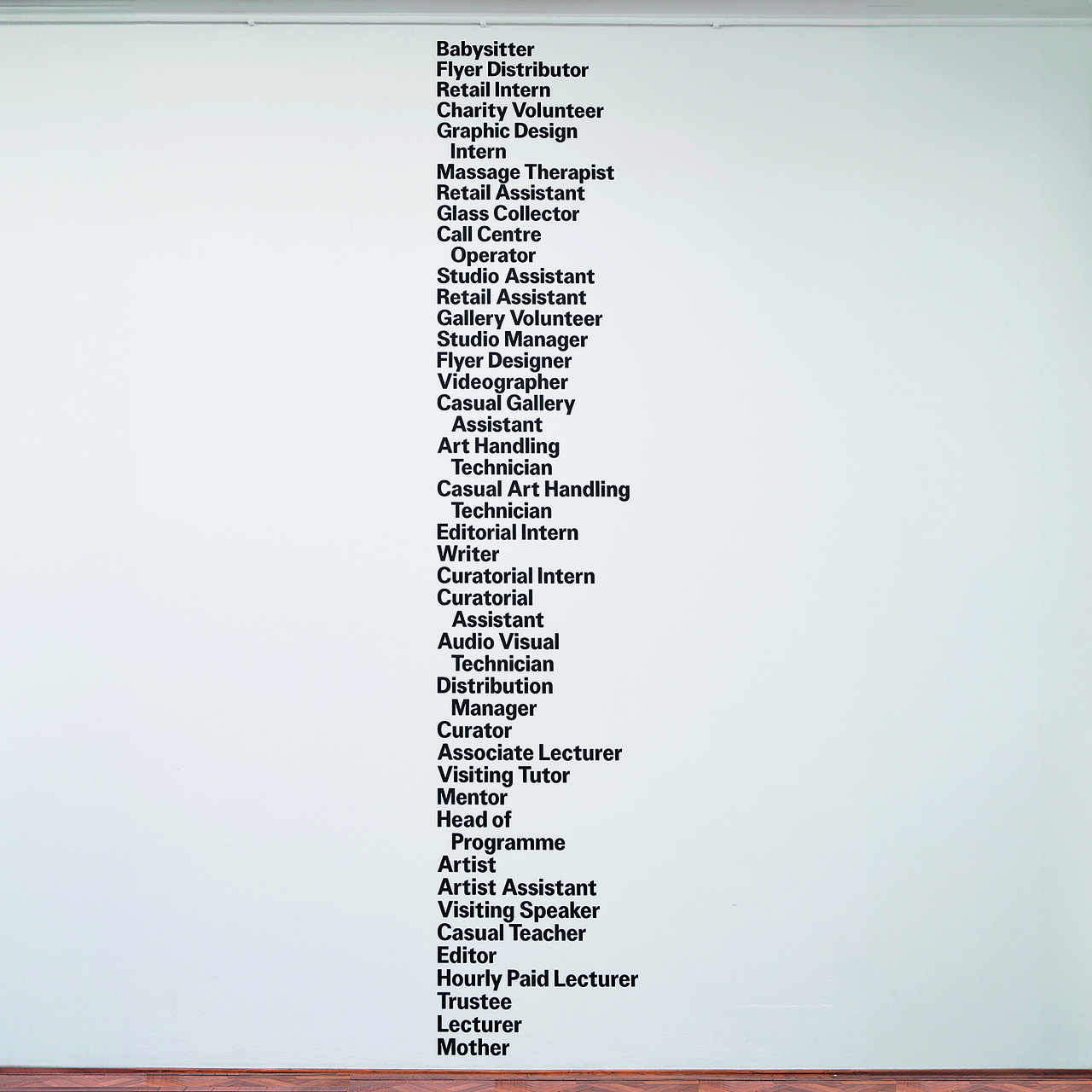

GHISLAINE LEUNG: When I started working in the art industry, I assumed a binary difference between public institutional and private commercial spaces. But the more I immersed myself, the clearer it became that philanthropy and patronage existed at every level. A lot of institutions are doing a huge amount of fundraising, and the donors are often the very same people who are buying in commercial galleries. Whereas many smaller or mid-level commercial galleries barely break even or operate at a loss. So, I’m not sure there is a clear delineation between commercial and noncommercial along the lines of private and public. The difference comes from how each entity functions, how they institute, and along what parameters: for-profit or not. A lot of this comes down to actions maintained, to people – how they work – and to the possibility of working differently. I worked for public art institutions and nonprofits in numerous capacities before starting to make art again – as listed in my work Jobs from 2024 – and this very much shaped my terms of engagement with them. The task of critique became a far more self-reflexive one, about how I institute as an artist – to think of the institution as a socially reproduced set of actions, systemically internalized and policed at every level within ourselves. I try to reckon with that in myself as an artist and hope that how I work questions some of the terms of production and reproduction within the industry. What happens if we engage with vulnerability rather than defense? Trust and reciprocity rather than control? Issues of dependency rather than those of autonomy?

Ghislaine Leung, “Jobs” (Score: A list of jobs held by the artist), 2024

ERIC GOLO STONE: An exhibition project authorized by the exhibiting artist and by the exhibiting institution is a locality of authority dynamics where art becomes inseparable from determining the critical uses of that institution. That is, I see art exhibitions as a distributive struggle over the extent to which an exhibiting institution’s infrastructures, personnel, and resources are organized, deployed, and allocated by artistic means. It’s a struggle with potentially far-reaching consequences when acknowledging the inherited continuities between exhibiting institutions and statecraft capitalism. This current political moment is, again, one of socio-ontological reckoning with the perceived purpose and actual usability of existing institutions. Iterations of conservative backlash to efforts at social reckoning are evidenced by the unrelenting maintenance of exhibiting institutions’ archaic conventions, which include nationalist-colonial accumulation, plutocratic self-legitimation, operational reliance on unpaid work, and trusteeship command managerialism. For exhibition-makers to transform the implementations of institutional governance arrangements means contending with high-stakes structural organizing, acquisitive realpolitik, and brutal legal realism. Whether commercial or not, institutionally mandated exhibitions are localities where art is inseparable from juridical regimes of property and capital. That ownable property and its attendant capital are fundamentally ensured by the state legal order exemplifies just how inextricably co-constitutive private interests and public institutions are. Plutocrats assert dominant authority over government spending because they recognize commercial entities are state dependents.

ZASHA COLAH: Lots of little thoughts came to mind listening to all of you. I’ve always worked in the public sector – museum- or university-based, or a biennial – so I have no knowledge of what it means to work in a fully private setting. But I come from Bombay, now Mumbai, where in the 1940s, modern art was entirely nurtured by private initiatives and galleries, small framing shops making exhibitions on the side. When working as a curator in a government-funded museum in Mumbai, I had to be really clever not to become the facade of the nation-state – to retain some distance from the edifice, from what it is meant to symbolize, keeping curatorial allegiance to complexity and to the audience, the receivers of cultural work. The task of the cultural worker has great potential to exceed simple allegiance to the constitution. In the wake of the 2008 financial crash, I cofounded the Clark House Initiative in Mumbai (2010–22) with other curators and artists in the city. We formed our union at a time when many organizations in India had lost their funding, when galleries had become rather conservative, which left little room for critical contemporary art. We had to address economic concerns quite thoroughly. Instead of seeking external funding, we worked on unspoken principles of gift exchange, bartering time or skills – such as carpentry or video editing – knowing that what was given would always come back tenfold.

But I see a very strange coming around of this question of private and public sectors in Berlin today. And this is maybe the way I interpret what Eric is saying – that it is really a case-by-case way of negotiating. While I, too, do not believe in a clear distinction between the public and private, it is an interesting distinction, especially now, since the latter is further removed from the government. In a moment in which politicians feel entitled to interfere with so many art shows (think of the German AfD party’s attack on Skulptur Projekte Münster, or the Greek minister throwing artworks to the floor in the National Gallery in Athens), private spaces offer symbolically safer contexts for artists. [2] Which is not to say that the private should be hailed as a refuge; rather, it offers a counterbalance, which is essential right now.

STONE: I agree, Zasha, that it’s important to recognize how artistic interests applied to an exhibition are distinct from those a politician applies to that exhibition. Ghislaine’s emphasis on the application of art as embodied instituting or infrastructuring is crucial. I often wonder how far artistic qualifications can be taken in an exhibition-making context and its networked relations. As a representative of an exhibiting institution, I make an urgent positive case for artistic methods, competencies, and capacities being vital, and practically necessary, to the operative structures of an institution supposedly purpose-built for art exhibitions. To make that case, it’s essential to understand that the exhibiting artists’ work for an exhibition project far exceeds exhibited outcomes. For some exhibiting artists, there are components of the artwork not intended for exhibition, which are equal to, and inseparable from, those components of the artwork intended for exhibition. Yet most exhibiting institutions don’t support this necessarily integrated and irreducible scope of the artistic work. Infrastructures of value and attention continue to be designated for those exhibited components of the artwork as hierarchically separate from those components of the artwork not exhibited. This is, of course, a means by which the management of exhibiting institutions territorially commands administrative infrastructures, preventing artistic methods from being applied to structural governance and reducing the role of exhibiting artists to producers of showed content.

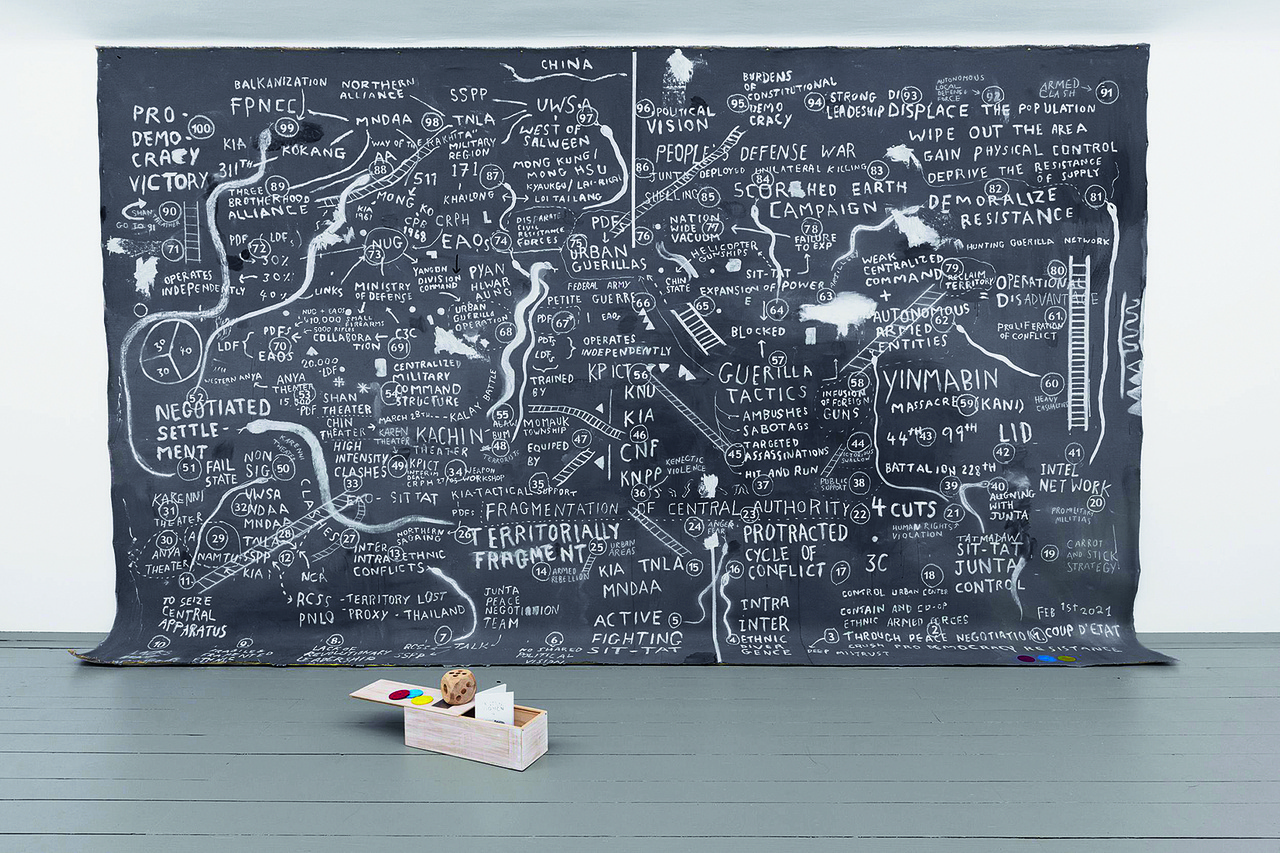

Sawangwongse Yawnghwe, “Coup and Resistance,” 2022, in “Extraneous,” EXILE (on the occasion of “Curated By”), Vienna, 2022

ANTONIA KÖLBL: Your practice is particularly instructive in this respect, Ghislaine. Would it be fair to argue that your work primarily takes place prior to and outside of the exhibition? For one, your artistic labor doesn’t directly produce a product that can be put on display. It’s the exhibiting institution that gives material form to your scores. And second, what ends up being on display – and I’m thinking of your show at n.b.k., which opens in June 2025, for instance – often links back to the material conditions under which you work, such as your artist’s fee.

LEUNG: When I started making work again, I tried to find a way to make a practice rather than a product. To concentrate on how I work, life inclusive, and let that generate a different type of art. And instead of trying to overcome or conceal the actualities of my material, lived conditions – like having a job, having a kid, being sick – I wanted to weave them in, to work with the resources I haven’t got, to take all the things I perceived as blocks and begin to build with them. So I began by setting myself these little exercises – sub-scores I perform as opposed to the scores the institution does – which I’ve been running for about 10 years now and which constitute a large part of my practice. They started with things such as no storage, no studio, no shipment. I added: not going to my openings, not going to my installs, and I set my own working hours. Basic parameters to find a way my art could work because I wasn’t there, rather than because I was. Importantly, there are sub-scores that engage in shame, laughter, acts of permission against my own fear, conservatism, hiding. So in different ways, they engage in vulnerability, at a formal and felt level, to lean into volatility and dependency as a generative means. A means of self-instruction in what often feels like a default setting of self-destruction. The issue of sustainability isn’t only economic, it’s emotional, and requires structural work that supports that.

However small and imperfect, these sub-scores created the way I work with scores, and they impact the way institutions work when they engage with my practice. I hadn’t fully acknowledged these sub-scores until recently, when I wrote them all down and decided to publish them in my forthcoming book, Holdings (2015–2025), made with the Renaissance Society. For me, it feels incredibly important to tackle the structural challenges we face in this way, via artistic practice itself. I don’t think my work primarily takes place prior to and outside of the exhibition, purely because I think so much of my work is dependent on that context, in basic terms of the performance of the score, on interpretation, distribution, circulation, and so on. I’m interested in de-alienating some of the conditions of artistic production and reproductive labor away from the notion of the individuated figure of the artist. To engage in the dependence of both art and artist on others. The fact that so much can and does happen without me is indicative of this. And I need it to do so because otherwise continuing my practice would not be possible, given the realities of the other incomes I depend on and those who depend on me.

COLAH: In thinking through the 13th Berlin Biennale, I also wrestle with the challenge of how to put the exhibition as a whole on view – which includes a long research process and even things that happen only after the show is closed. One of the questions that has led me to this has been: Is the act of saving a river the artwork, or is it the documentation of saving the river with the community, or is it the actual going around the bureaucracy, the legal messiness that is needed to save the river? Which one is really the artistic work? It was Milica Tomić who distinguished between this triumphal moment of the exhibition and exhibiting, which is a much longer process, but we don’t have a satisfactory technology to put exhibiting on display. [3]

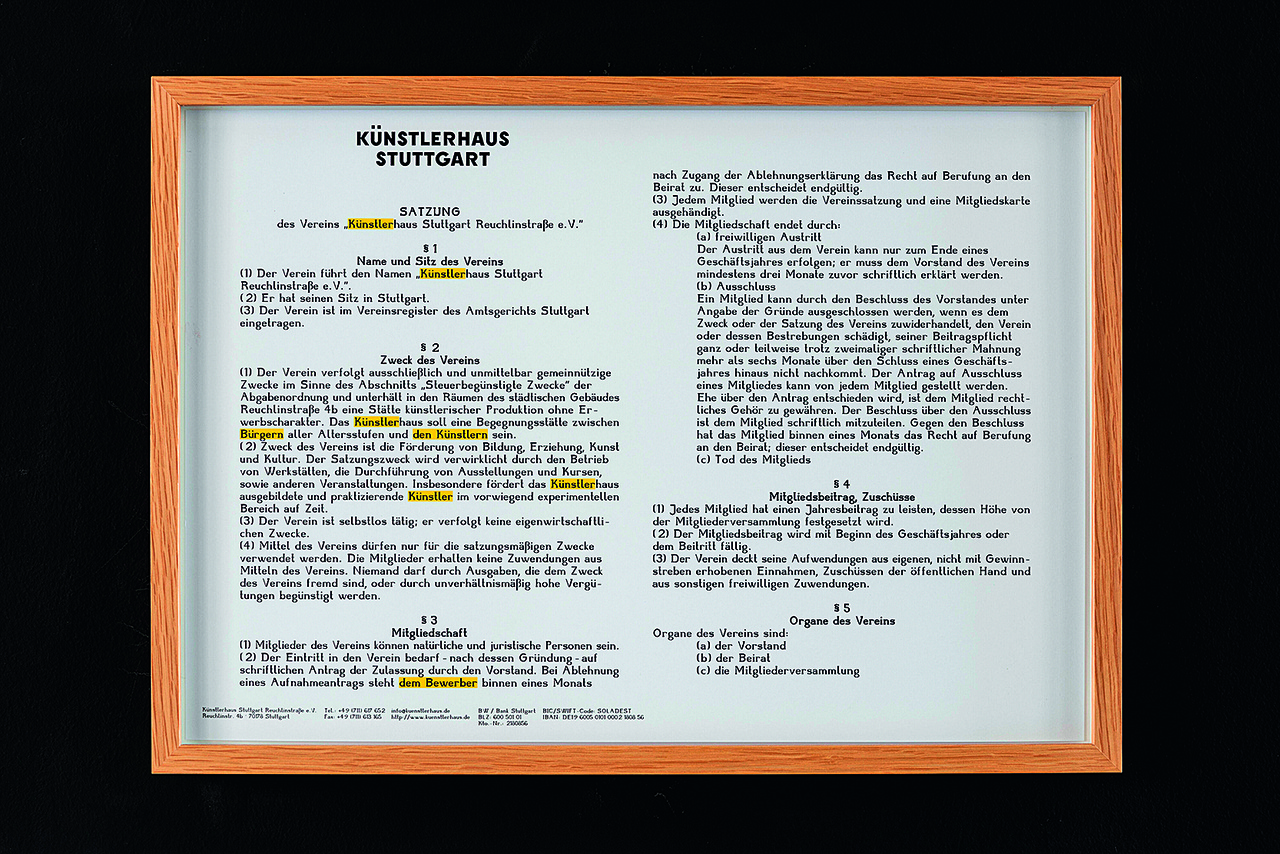

“Ramaya Tegegne: Unusability Might be Assumed Unless There are Signs Indicating Otherwise,” Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, 2021

KÖLBL: Why is a public sharing of the exhibiting, with your audience or with receivers of cultural work, as you put it earlier, desirable to you as a curator? Especially for large biennale shows, one could argue that they are already showing too much. And is exhibiting the research really new? As I remember, the last Berlin Biennale put many research-based works on display.

COLAH: Interesting – we do not need to make it all triumphal, no. Even so, this biennale elongates the process of ongoingness exhibited as it ties to the spoken word and contemporary orality. In the current global political context, I have to keep in mind the things that have never entered display culture because they could not be documented or made visible. I am thinking alongside the experimentations by Françoise Vergès in Réunion, where a museum was being designed to carry oral cultural memory.

I suppose I’m seeking modes of putting the artistic claim itself on display. It was also Tomić who emphasized in our conversations the power of the artist’s claim – that something is art because the artist says it is. This, I would argue, can be extended to looking at how artworks have the ability to set their own claims and laws in motion. Here, art’s counter-wager to notions of legality comes into play for me.

Finally, my conversations with artists about their claims led to thinking through the exhibition format itself. Is it outdated, or is it something to hold onto? I started to think together with artists of the exhibition format as a technology for slowing down time, so one can really sit with things becoming slowly visible, in relation to other things that one would want to think with.

LEUNG: In answer to your question – What is the work: Is it the claim, is it the action, is it the thing? – I would argue, all of it is. All of it always was. It’s a false notion that it is one thing or one person, a notion that comes from alienated relations that are not invisible but absolutely hidden. And they’re hidden for particular reasons: for reasons of control, fear, and denigration that implement the construct of value, of objects and people. It isn’t only production that is concealed but also the means of reproduction that underlies and maintains this productivity. The issue of maintenance is key. This isn’t about the dematerialized artwork as much as the immaterial labor of the lives around it. Constitutive decisions on the production and exhibition of artworks are as reliant on institutional labor as artistic labor. Decisions defined by protocol, regulation, budgetary limitations, timescale, aesthetic choices, and curatorial concerns, as well as institutional anxiety, fear, and conservatism, are established well before exhibition, or even invitation. I’m interested in pushing some accountability back onto the institution through the score’s act of interpretation. Because in other ways the fact that the work is the installation, the exhibition, the exchange, the transaction, the conservation, the interpretation, the discourse, and more presents a great liberation to me: It is not all on me. If I thought it was, I don’t know if I’d even be able to make work. I’m excited by the weird points of uncertainty, friction, and scariness, when the integrity of the work dissolves into this co-constituting many-ness of people.

Ghislaine Leung, “Holdings” (Score: An object that is no longer an artwork), 2024

When I started at Künstlerhaus Stuttgart in 2020, I invited artists who were going to exhibit at the institution to work with stakeholders and legal counsel on overhauling the exhibition contract. A central component of that new exhibition project agreement template was an artist fee structure with a minimum standard, a 50 percent advance, and a specified guarantee for the artist to receive their fee. The invited artists and I considered how advance payment guarantees for exhibiting artists could protect their exhibition from being canceled by the exhibiting institution. That exhibition agreement template also had an origins-of-financing clause, a section of the contract developed with an artist who was also a member of the board. There was a budget clause stipulating that exhibiting artists had access to a fully itemized budget, not solely the artists’ production budget. That budget disclosure meant that exhibiting artists were less alienated from spending decisions and labor positions. In addition to overhauling the exhibition agreement, I worked with exhibiting artists on legal-aid infrastructure for visa-applicant, migrant, displaced, asylum-seeking, and refugee-status artists, as well as a code of conduct instituting means of recourse more exacting than those mandated by law. Exhibiting artists were central to each of these policy initiatives, not solely to develop institutional capacity for inclusive governance arrangements and contract bargaining but also to develop art’s capacity for social possibilities that exceed the limits of a law and rights framework.

LEUNG: The presumed neutral framework of the exhibition form often relies on a set of structural or organizational defaults that are usually regulated by contracts, as well as on a set of informal and deregulated internalized behaviors that are understood and socially reproduced. The relation between the two always makes me think about The Tyranny of Structurelessness, a 1970 speech by Jo Freeman that she later published. By analyzing the self-organization of second-wave feminist groups who rejected any kind of structuring order, Freeman argues that what was intended to provide greater freedom resulted in perpetuating the existing oppressive structures. As the groups had nominally abolished hierarchies, domination within them could not be accounted for. If you want to avoid social reproduction of this kind, you cannot simply take away all structure. We are dealing with a neoliberal cultural system of deregulation. I think we are past the operative point of deconstruction being adequate; the master’s tools will not dismantle the master’s house. Getting a seat at the table does not intrinsically question the structure of the table itself. Nor does refusing that seat. In some ways, any attempt to intervene in or become a top-down structure perpetuates it. So, what, then, are the stipulations and claims, the actions and infringements, you want to implement, from the ground up, in the structures you work in as an artist, as a curator, as an editor? Ones that work with where we are, what we haven’t got? Productivity is reliant on reproductive labor; if we were able to stop denigrating that labor, perhaps we could mobilize it differently. I can no longer biologically reproduce; I have to deal with that, to think through not reproducing to reproducing differently.

Zasha Colah and Valentina Viviani, Curator and Assistant Curator of the 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art

VOGEL: In the past years, notions such as care, equity, and solidarity emerged as a theme, from small artists’ projects to large biennales. This was always accompanied by critical inquiries into how these ideals could go beyond liberal lip service and actually be materialized. The recent and ongoing changes in cultural policies underscore the urgency of this line of critique. When thinking about the translation of material conditions into the form of the exhibition, I believe it’s helpful to draw from the history of institutional critique, not least because it’s deeply connected to Ghislaine’s practice and that of your contemporaries, like Carolyn Lazard and Park McArthur, and to some of the artists Eric showed at Künstlerhaus in Stuttgart during his tenure there, such as Eva Barto, Maria Eichhorn, Niloufar Emamifar, Andrea Fraser, Flint Jamison, Bea Schlingelhoff, and Ramaya Tegegne. How is this newer wave of institutional critique – also termed “constitutional critique,” to use Ghislaine’s terminology, or “infrastructural critique” by the late theorist Marina Vishmidt – different from earlier iterations, and more importantly, how does it deal with the pitfall of potentially preserving or even amplifying the system it critiques? How can the purely symbolic be avoided?

LEUNG: Maybe what’s key is a more expanded or embodied notion of institution that brings in other systems: my own life, my own circumstances, the resources I don’t have, and the limitations I feel bound by. This is what so many of the artists you mentioned do with such rigor. And from necessity. Such a difference in practice innately questions what constitutes an artwork, but it also does so through how we work. Maybe it’s not so much about what we do, as about what we don’t, can’t, or simply no longer want to. For me, it’s not about absolute positions: I don’t want to drop out, I want to stay in so I can keep stopping. It’s a question of maintaining these micro-withdrawals. And I can do this and keep doing this because they aren’t big shifts. If systemic prejudice is perpetuated via a system of microaggressions, then I think it can be shifted at that scale too, in little acts of vulnerability.

All of this means that my exhibitions are preceded by a huge raft of negotiation, especially compared to the rather minimal scope of the work as it is displayed in the end. This requires trust and reciprocity. As soon as there is a willingness for alterations, I’ll start bringing in something from my heart. The work, in terms of a practice, is very much about making that emotional space happen; the space for discussion – and disagreement. A politics of exhibiting. To exhibit feels vulnerable, which is what causes so many defenses to ensue around it. But they often lock out what’s important. Exhibiting, as opposed to exhibition, might be less about technology than taking heart.

I feel if we keep on only looking for a perfect, un-sublatable critique, then no critique will happen. It becomes puritanical, premised only on measurable results. We can’t afford critical distance, or objectivity as a guarantee of safety. We are too far in, feelings need to be risked, and you need support to do that. We need it all, and we need each other, differences included. Things will and won’t work, or will work in ways you never even imagined. I think we need to tolerate that uncertainty, ambivalence, contradiction: It’s what’s felt in the push and pull of even ourselves.

“Bea Schlingelhoff: Declined Declinations,” Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, 2022

While we hear a lot about censorship of exhibited outcomes, there is a great deal of artistic work done prior to an exhibition opening that is met with suppression or backlash by supervisory authorities. In part because of nondisclosure arrangements, journalism and art criticism don’t report the internal governance struggles of exhibitions, even when reporting that an exhibition was canceled. Rarely do we see detailed reporting on how an exhibition staff curator, with all their responsibilities but very little authority, was fired or how a director, who serves at the pleasure of the board, capitulated or was dismissed. If you look through Michael Asher’s archive of exhibition files, you see that even with a privileged artist like him, many proposals for exhibition projects were rejected by management owing to political differences – for instance, with sponsorship arrangements. It’s significant that Asher conditioned his work for an exhibition on the exhibiting institution terminating its sponsorship from Nestlé.

Exhibiting artists have a tactical advantage when it comes to organizing workplace conditions at exhibiting institutions. It’s exhibiting artists who can strategically time the withholding of content in ways that connect individual rights and liability to shared rights and collectivized strike. Most exhibiting artists can recognize work organization viewed from the perspective of wageless work and worker-to-worker organizing. Exhibiting artists are not external to institutions, so they really need not be external to mass-membership unionization, collective bargaining, and other coalitional pursuits of legally enforced workplace conditions. And yet, these are still accession efforts that comply with the law and rights framework. So if art is burdened by that inseparability from the law, how might art then burden the law with overriding force? I’m interested in the artistic potential of that inseparability.

Ghislaine Leung, “Times” (Score: Access to exhibited works is limited to the studio hours available to the artist. Thursday 9AM–4PM, Friday 9AM–4PM. The exhibition space may remain open regular hours), 2022

But let me go back to Felix’s question, which makes me a little restless: care, equity, solidarity, sustainability, and institutional critique … it seems like we could have discussed the same question in times past. That’s the easy stuff, which I love and have been training for through my work. But right now, there are so many emergencies happening all around me – I do feel ill-trained or unequipped, and I think this is worth discussing, too. Take the increasing encroachment of politics into spheres mostly deemed safe from harmful intrusion. In India, the parliament just passed the Finance Bill 2025, which allows the state to break into people’s virtual space if state officials have reason to believe one’s income tax declaration is incorrect. All of your virtual space: any social media, any email, even encrypted ones. This is poised to attack cultural, intellectual, and journalistic institutions through a personal door.

We have challenges in addition to what Felix has been saying so far. It’s not only the work happening in, with, and against institutions as institutional critique; institutions themselves are so precarious right now. In light of the recent economic developments in Berlin, for instance, some intellectual discourse about material conditions of exhibitions has almost lost its meaning. There are huge cuts, people are in and out of jobs, contracts are extremely short-term. I don’t see a lack of care but a high level of instability within the institution.

Environmental factors and repressive migration politics have also led to increased instability. I am working with artists who have just experienced an earthquake and are unable to communicate because they don’t have electricity. I am working with artists for whom laws are constantly in flux. In recent months, there have been those who have to fear for their visa or residency status, which leads to extreme carefulness around what they make public in their name.

STONE: We have to offer purposeful alterity from that double bind of continuing precarity and outright elimination of institutions. One can’t help being ambivalent about defending exhibiting institutions: As educational and social welfare institutions, they are austeritized, yet they are also direct beneficiaries of nationalistic accumulation. An apparatus established by state capital can never be liberated, but that operative machinery of trauma is necessarily utilized in service of reparations. There are courageous non-capitulating people engaged in the critical project of reparations within systems that are irreparable. There are allies, friends, and family working in and under those inimical institutions. To concede the struggle for organizing the uses and usership of inescapable institutions is to accept the hierarchically administered ruination, evisceration, expulsion, and death-dealing of necropolitics. Exhibitions can offer a modality of anti-necropolitics. As the state forecloses institutional capacity for reflexivity and dissent, it’s still important that critical negation occupy space within institutions, including exhibiting institutions as consequential sites of lived struggle.

Ruins of Ennigaldi-Nanna’s museum, Iraq

COLAH: From my point of view, the museum is not a didactic machine that was invented in the West, but rather that the first museum may have been in Ur, Iraq, in 530 BCE, Mesopotamia, curated by Ennigaldi-Nanna, a priestess and princess who put different objects from vastly different time periods and locations together in the same rooms. We cannot be sure what it was, but it looks like one, and so it has been called a museum. If you go from this interest in different things talking to each other across place or time, then the museum is a very general concept – as is, by extension, the art institution. It also seems like those places are often the first to be destroyed in times of political and military upheaval. In the Battle of Khartoum in 2023, following Sudan’s coup in 2021, among the first institutions to be deliberately bombed or targeted were the archives and the museum. Why? And why in 1933, over here, were arts and cultural spaces the first ones to be shut down in the process of Gleichschaltung (literally: bringing into line)? What makes culture structured collectively so threatening to politics? I’m always surprised at how quickly this disintegration unfolds.

KÖLBL: I’d like to come back to the frustration you expressed about terminology, Zasha, which I share. It almost feels like a moot point to reiterate the imminent crises we’re now experiencing and that, for the moment, seem to be accelerating. Which is precisely my concern: I feel like I’m lacking the language to adequately address the current moment. Is there language you find helpful right now? In what you’ve put out so far for the Berlin Biennale, Zasha, you work with an explicit shift in terminology away from the notion of identity and toward that of dignity.

COLAH: I think you answered part of this in your invitation to us when you stressed that the increasing and undifferentiated questioning of identity politics must be critically discussed. That’s part of the problem: undifferentiated language – especially since language can be appropriated so easily by the (far) right. I myself question identity politics – but so does Elon Musk. Where does that leave me? On Elon Musk’s side? No. That’s why it’s so important to articulate the differences and nuances of meaning and avoid simplification. We in the cultural field need to be difficultating how we wield language. Art also makes imagination, ideas, and notions plastic. And in this sense, the plasticity of art language is dense; it can hold multiple meanings, ambiguities, differentiations, contradictions, difficulties that fuse like sedimentary rock into one plastic thing. I think it’s easier, somehow, for society to accept difficulty in that form. Of course, artworks use language, but what the plastic element adds can be manifold. It’s very useful in climates where people are so quick to willfully misunderstand or when one cannot speak out clearly. We have to apply the kind of artistic thinking we discussed before, both to aspects like budgets and contracts, as well as to language and representation.

STONE: Identity politics, or standpoint epistemology, originates in substantive thought and remains an unrealized project of recognizing difference without forming hierarchy. We must not relinquish these crucial burgeoning ideas to the narrow interests of elite capture and right-wing backlash. There are white men who hate identity politics because they want to reaffirm the lie that this is a post-racial world of competitive accession. Rich bosses tell poor workers to crusade against any workplace antidiscrimination training and forget wealth inequality. Obviously, we should have workplace antidiscrimination training and not forget about wealth inequality. We need not accept violently reductive fictions and dichotomies. Rather than brush aside or conquer differences, we have to be socially capable of recognizing lived differences and do the structurally transformative work that confronts hierarchies. It’s a project grounded in conditions of reality that pursues an expansive critical horizon. I appreciate the emphasis on artistic methods that exceed the law and rights framework, though I don’t think that exceeding that framework necessarily means eliminating it. In contrast, if the law even slightly expands to protect discriminated parties, we often see that it then selectively dismisses or very quickly strips those rights – autocracy and plutocracy wield the law to drastically narrow the scope of beneficiaries.

LEUNG: I think certain languages are used because they’re efficient. One good thing about art is that it’s not always very efficient, and I do think that’s one way we can short-circuit some of what you both are talking about. There’s a politics in inefficiency, in its refusal, its lacking. Whatever tool you use will always be redeployed; whatever works will always be taken. But what stubbornly refuses those metrics cannot be claimed by them. That art does not perform to criteria is in many ways its strength: It exceeds those criteria. Here is the experimental, plasticity, a reckoning with an unknown. Every refusal of a known is also an affirmation of an as yet unknown. Artists have to deal with precarity and instability in many ways, and perhaps institutions can learn something from that – about engaging with what art, and what we, cannot do: what we are all struggling with. That’s not a thematic; it’s an action.

Zasha Colah has been co-artistic director of Ar/Ge Kunst, Bolzano since 2023 and a lecturer in curatorial studies at Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti, Milan since 2018. She is the curator of the 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art.

Antonia Kölbl is an art historian and editor-in-chief of TEXTE ZUR KUNST.

Ghislaine Leung is a British conceptual artist. Her work uses score-based instructions to radically redistribute and constitute the terms of artistic production. Leung has shown her work internationally, most recently with a solo show at n.b.k. in Berlin in 2025. Her third book, Holdings (2015–2025) is forthcoming.

Eric Golo Stone is a writer and curator. His work emphasizes structurally transformative artistic methods of institutional critique.

Felix Vogel is a professor of art and knowledge at the University of Kassel and a member of the documenta Institute.

Image Credit: 1. Courtesy Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, photo Frank Kleinbach; 2. Courtesy of Ghislaine Leung and Maxwell Graham; 3. Courtesy EXILE Gallery; 4. Courtesy Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, photo Frank Kleinbach; 5. Courtesy Ghislaine Leung and Maxwell Graham; 6. Courtesy Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, photo Frank Kleinbach; 7. Photo Raisa Galofre; 8. Courtesy Ghislaine Leung and Maxwell Graham; 9. Public domain.

Notes

| [1] | Marina Vishmidt, “Between Not Everything and Not Nothing: Cuts Toward Infrastructural Critique,” in Former West: Art and the Contemporary After 1989, ed. Maria Hlavajova and Simon Sheikh (MIT Press, 2017), 266. |

| [2] | “AfD gegen Skulptur Projekte,” Antenne Münster, April 10, 2024; “Greek Politician Vandalizes ‘Blasphemous’ Works at Athens Museum," Artforum, 13. März 2025. |

| [3] | “Exhibiting Matters,” themed edition, GAM Architecture Magazine, no. 14 (2018). |