CHALLENGING ART HISTORY FROM A ROMA PERSPECTIVE Timea Junghaus in Conversation with Burcu Dogramaci

Charly Bechaimont, “Politique de l’accident: deux hommes faisant l’amour,” 2024

BURCU DOGRAMACI: Dear Timea, I’m more than happy that we meet. As an art historian, activist, and political stakeholder, you have dedicated yourself to Roma art for many years and have contributed significantly to its increasing presence in contemporary exhibitions. Could we start with a short look back on your studies?

TIMEA JUNGHAUS: I studied art history and cultural anthropology in Budapest, Hungary, at Eötvös Loránd University. Then I continued my studies toward a PhD in media theory, which is still in progress. As a first-generation intellectual, it took me 14 years to complete my art history studies, largely because I was navigating academic language, text, and institutional contexts. Over those years, I found it striking that in all my studies, I had never encountered an authentic depiction of or by a Roma – not in libraries, archives, or in the courses I attended. The presence of Roma in the visual arts has remained largely unexamined within the grand narrative of art history. Depictions of Roma appear as early as the 12th century, with a striking proliferation in the Flemish and Nordic Renaissance by the late 15th century. These images exist and are – undeniably – woven into the fabric of European artistic heritage. Paradoxically, however, the discourse surrounding them has remained largely undeveloped. When Roma have been represented, these portrayals have often relied on entrenched stereotypes – racialized, exoticized, and sexualized projections – rarely subjected to critical examination. If any historical writing has addressed Roma culture, it has frequently overlooked or diminished our artistic and intellectual contributions, unfolding in the absence of Roma. It is only through a paradigmatic shift – through an insistence on agency and presence – that we begin to reshape how Roma are seen and understood.

DOGRAMACI: You are describing the absence of Roma artists from art historical discourse and the exclusion of Roma voices from the historiography of Roma art. Is it possible to explicate the notion of Roma? In Germany, the term Sinti und Roma has been familiar for many years. But does that really get to the heart of the matter?

JUNGHAUS: In Germany, the politically correct term is Sinti und Roma. In the international context, Roma is the politically correct term we use for naming the largest minority in Europe, approximately 14 million people. However, the local denomination changes by the country: in the UK, we would say Gypsy, Roma, Travellers. In France, we would say roms, manouches, or gens du voyage. In Spain, we would say gitano or gitana. This integrative term Roma actually describes over 23 subgroups, each with distinct cultural, linguistic, and artistic traditions. For example, the Kalderash Roma are known for their metalwork craftsmanship, while Lovara Roma have a rich oral storytelling tradition that influences contemporary performance art. Meanwhile, Spanish Gitano and Gitana artists often engage with flamenco and other performative expressions. When we say “Roma,” there’s always a risk of homogenizing Roma identity, which is in fact fluid, multifaceted, and deeply shaped by migration, persecution, and adaptation. The challenge lies in recognizing Roma art as a uniting, broad, and evolving category but also making space for its complexity and plurality. It’s really a wonderful term, a liberating and inspiring notion to work with.

Selma Selman, “You Have No Idea,” 2016

DOGRAMACI: It’s very instructive how you describe “Roma” as something that shifts our perspective. I wonder how we can adapt this to art, how we can understand the notion of Roma art.

JUNGHAUS: I am obsessed with the notion of Roma art, which is best understood as a cultural or aesthetic practice that emerges from the lived experiences, histories, and identities of Roma people across different regions. More than a category, Roma art is a claim: It is rooted in resistance to oppression and in the affirmation of Roma identity through visual, performative, and conceptual means. For example, the work of Małgorzata Mirga-Tas engages with historical imagery to rewrite Roma narratives into European art history, while Selma Selman’s performances challenge economic and social exclusion, embodying the resilience and defiance central to Roma artistic expression.

DOGRAMACI: It’s very interesting that you mentioned resistance as embedded in Roma art. I wonder if we could understand it as a transnational concept and if it thereby could help in transgressing the longing for national categorization or ordering in art history. I would suggest that the concept of Roma art extends beyond such categories.

JUNGHAUS: Absolutely. Your question inspires a wide range of potential understandings of Roma art. This is not merely an ethnic or minority category – it is an intervention into the structures of the art world itself, challenging and rewriting art history from a Roma perspective, which, as you noted, is inherently transnational. It aligns with a broader reimagining of Europe – not as a homogenous, white, Christian construct but as a space shaped by millennia of migration. Roma, among Europe’s earliest migrants, have sustained their presence through resilience, multilingualism, cultural adaptation, and borderlessness. Education, entrepreneurship, and creative opportunities have always been central to the Roma experience, forming the core of Roma subjectivity. And this is where the strength of Roma art lies: Since the late 1960s, it has been the most vital vehicle for articulating Roma identity, asserting presence, agency, and artistic sovereignty in the contemporary cultural landscape.

DOGRAMACI: I am thinking of concepts such as “postmigration,” which emphasize that societies are constituted by migration and thus lead to new understandings of art and art-making.

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, “Singoalla Millon,” 2023

JUNGHAUS: Roma communities have historically existed across borders, adapting to different cultural, social, and political environments. Unlike the categorizations in art history, which are based on territory and statehood, Roma art reflects transgressive notions such as diaspora, movement, and hybridity. In recognizing that European societies are shaped by historical and contemporary migration, Roma art also disrupts this Eurocentric national canon. I will also stop at nomadism, which has been connected to Roma, but I don’t like to use the term.

DOGRAMACI: Why? Could you explain why is it difficult to work with the terminology of nomadism – a concept that is, among many others, connected to the émigré media philosopher Vilém Flusser?

JUNGHAUS: The challenge in referencing nomadism, even in the vein of Vilém Flusser’s émigré philosophy, lies in disentangling its conceptual richness from the historical realities of forced displacement, systemic exclusion, and the persistent exoticization of Roma and other marginalized communities. I personally believe that the 1,000-year history of Roma in Europe is actually a history of smaller and larger genocides, evictions, and violent events. The nomadic life was not a choice but a way of fleeing and running from different forms of violence and exclusion. I avoid the term “nomadism” in my writings because it is frequently exoticized, romanticized, and even sexualized in relation to Roma people. Historically, this misrepresentation has led to a distorted perception of Roma identity in art, often portraying Roma as eternal wanderers without agency or history. These depictions reinforce stereotypes rather than acknowledge the forced migrations and systemic marginalization that shaped Roma mobility. By critically engaging with these narratives, contemporary Roma artists present nomadism not as a romantic ideal but as a response to displacement, as survival, and as a political and aesthetic force. When we reevaluate and reembody this notion, we disrupt the illusions connected to it and we gain access to stories otherwise untold in Europe. We see this in many of the works of the Gen Z of Roma artists – for example, by Charly Bechaimont, Anita Horváth, or Lila Loisse. This is also connected to the idea of reclaiming the camp. Ethel Brooks’s beautiful text “Reclaiming: The Camp and the Avant-Garde,” based on Hannah Arendt’s notes on the modern refugee, inspires a reexamination of the terms that have been stolen and hidden from us.

DOGRAMACI: Can the current attention given to Roma art also lead to a reexamination of the Porrajmos, the persecution and murder of European Roma and Sinti by the National Socialists, which has long been little commemorated? I am thinking of Ceija Stojka, whose work, which refers to her internment in and survival of Auschwitz, was also present at Documenta in Kassel in 2022.

Emília Rigová, “Occupo ergo sum!,” 2024

JUNGHAUS: Our recognition of artistic practices that preserve the memory of the Roma Holocaust have profoundly impacted academia – shaping art history, Holocaust studies, and historical scholarship. Until a decade ago, Roma were largely taught that they were collateral victims of the Holocaust. But as Roma historians, artists, and researchers delved deeper, they uncovered stories that transcend victimhood and reshaped our understanding of the past. The transformative power of creative practice in transmitting this history is extraordinary.

DOGRAMACI: You emphasize that the act of resistance and active survival was not part of the Roma Holocaust histories told by others. There was a need for a historiography of Porrajmos through Roma people themselves.

JUNGHAUS: The stories of Roma elders, survivors, researchers, and artists reveal a history of agency, resistance, and survival. Roma developed intricate escape strategies – hiding Jewish and Roma children together, sharing resources, and using their deep knowledge of forests and fields to outmaneuver fascist forces, often surpassing even anti-fascist movements in this expertise. The Romani language itself became a tool of resistance, serving as a clandestine means of communication. Over the past decade, we have reclaimed and documented these histories, and the role of artists in this process has been extraordinary. Historians and artists like Ceija Stojka, Karl Stojka, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, and Emília Rigová have powerfully demonstrated that Roma were not passive victims but active agents of survival and defiance.

DOGRAMACI: The ongoing work on the present and the history of Roma art is an important part of your practice. When you described your path at the beginning, you said you studied art history, but you are much more than an art historian. You are a curator, your write and communicate about Roma art, and you are also an activist and part of the transnationally organized Roma community. How are all of these interrelated and connected with each other?

JUNGHAUS: Actually, most of the colleagues who are shaping the art world work at the intersection of scholarship, curation, and activism. I do work to establish platforms where Roma artists can be recognized and engaged in critical dialogue with the broader art world. And, as an art historian, I focus on decolonizing narratives, ensuring that Roma art is not a peripheral subject but a central part of contemporary art discourse.

Robert Gabris, “Error – Roma Corporeality and Their Non-Binary Spaces,” 2021

DOGRAMACI: You have contributed greatly to the fact that Roma art has attracted a lot of attention recently. We’ve already mentioned Mirga-Tas and Selman. I wonder if you could look back briefly and describe some changes in the visibility and also in the recognition of Roma artists in contemporary art in recent years.

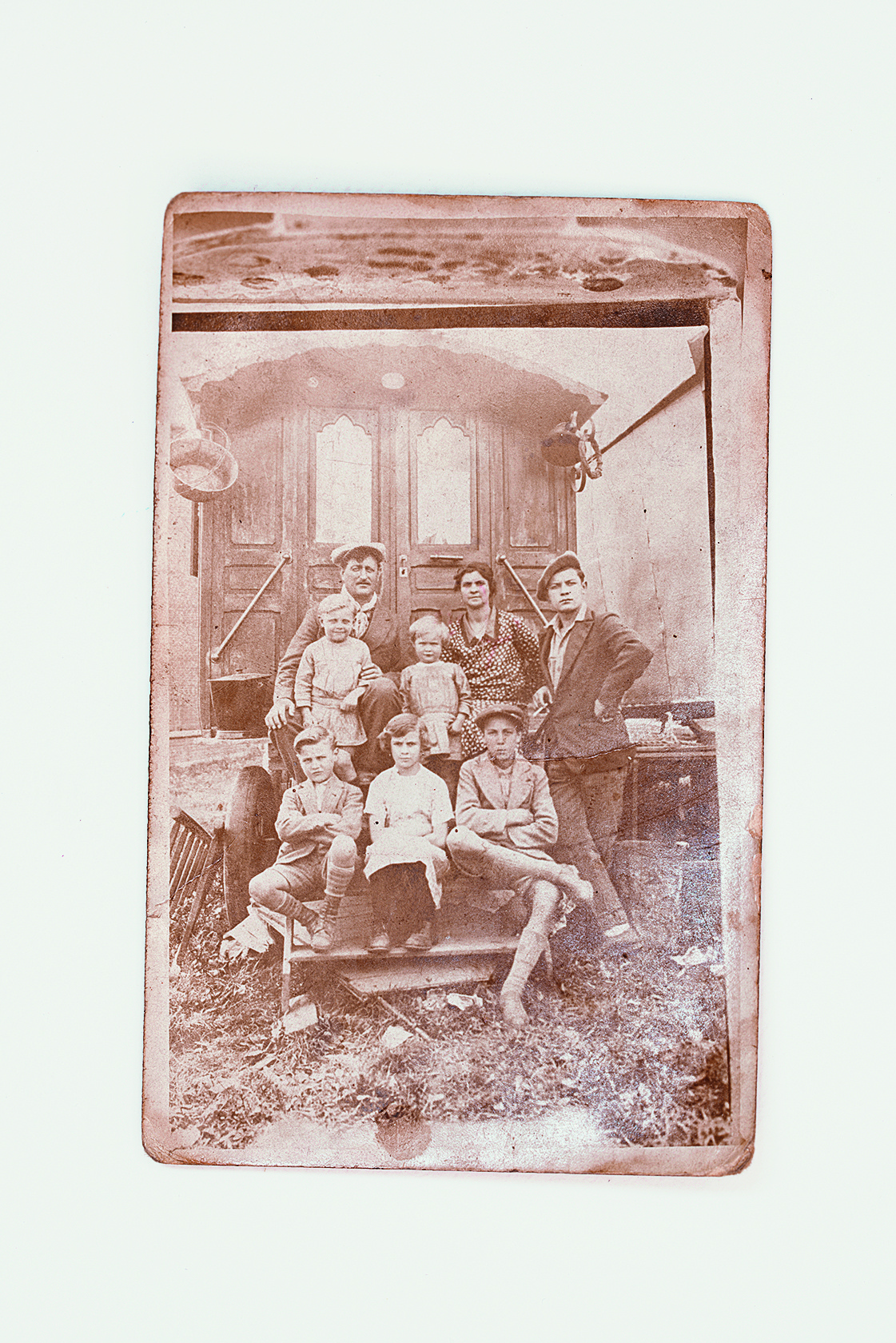

JUNGHAUS: I always see the historical timeline: from 1968, when Roma collectively reclaimed Roma authorship, to the First World Roma Congress, held in London on April 8, 1971, which marked the first international gathering of Roma intellectuals, where thinkers and leaders from across Europe came together to exchange ideas and forge a collective agenda. Their collaboration resulted in historic agreements on key symbols such as the Roma flag and anthem, the designation of April 8 as Roma Day, and transformative principles including Roma self-determination, the recognition of the Roma Holocaust, and the assertion of Roma authorship. This conception of authorship is a foundational precondition for the recognition of Roma creative practice. Since the 1970s, the growing presence of Roma scholars across disciplines has been vital.

DOGRAMACI: The institution you founded in 2017, the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture (ERIAC), has played a central role in these developments over the last years.

JUNGHAUS: ERIAC functions much like a Goethe or Cervantes Institute, but for a transnational minority like the Roma, coordination among diverse subgroups, communities, and national contexts is even more essential. The revival of RomaMoMA at documenta fifteen in 2022 marked a significant moment – a concept first envisioned in 2005 by young Roma in Budapest, later reclaimed by OFF-Biennale and ERIAC. Today, RomaMoMA exists as a dynamic, evolving presence, appearing in various projects, sometimes anonymously, beyond our own awareness.

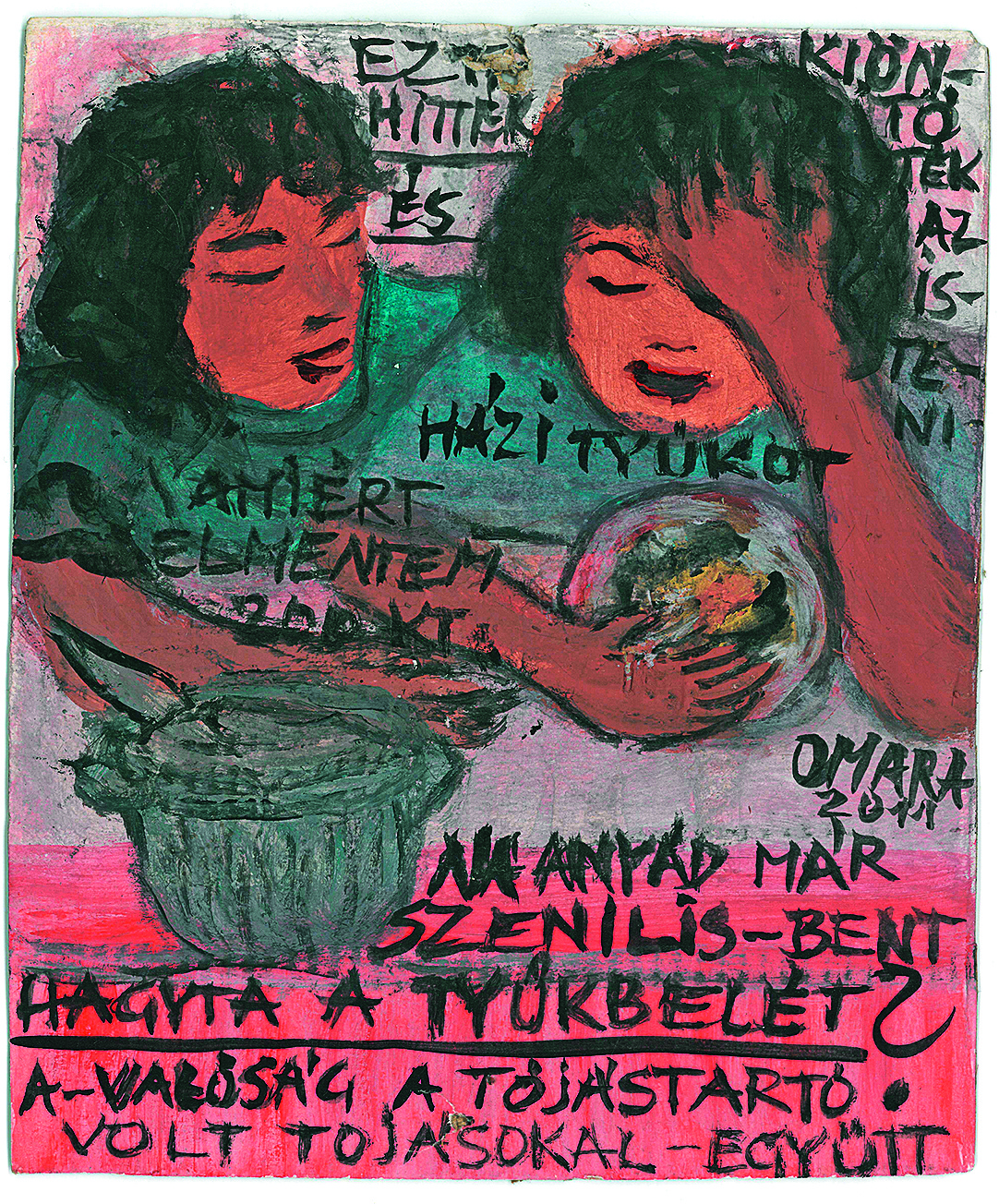

Mara Oláh, “They believed it and poured out the divine homemade chicken (soup), for which I drove 200 km. What the hell, your senile mom left the chicken guts in it? The reality was ... it was the egg carton – with the eggs still in it,” 2011

DOGRAMACI: What was the idea behind RomaMoMA? Its name refers to a very canonical art institution in New York City.

JUNGHAUS: RomaMoMA is the Roma counterpart to the Museum of Modern Art – our assertion of the need for a Roma museum. Realizing such an institution would require substantial multinational investment, but beyond its material form, RomaMoMA is also a political claim. We embrace the prefigurative, a concept deeply rooted in the Roma experience, alongside the performative, allowing us to manifest this imagined museum across multiple locations wherever the need for its existence arises.

DOGRAMACI: What do you think about smaller, private initiatives like Mara Gallery, which Mara Oláh opened in her Budapest apartment in 1993? How important are these smaller institutions in comparison to ERIAC, for example, which is a very representative institution, located in the political center of Berlin, close to parliament?

JUNGHAUS: We can highlight Documenta and Manifesta, as well as the remarkable presence of Małgorzata Mirga-Tas across institutions like the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht and Tate St. Ives just last year. Selma Selman’s stunning exhibition at Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Robert Gabris’s powerful work at Vienna’s Belvedere 21, and Delaine Le Bas’s nomination for the Turner Prize all underscore the growing visibility of Roma artists at the highest levels of contemporary art. Emília Rigová, now teaching at a fine arts university in Slovakia – a country where Roma continue to face violent discrimination – further demonstrates the critical contributions of Roma artists to the cultural landscape. This thriving artistic production extends beyond major institutions. At ERIAC, we actively support this ecosystem through such initiatives as the Villa Romana Residency Programme, which brings emerging Roma artists into the international art scene.

Selma Selman, “Platinum,” 2021

DOGRAMACI: I would like to return to writing art history and its relation to these activities of ERIAC. Your Wikipedia entry emphasizes that you are the first Roma in Hungary to have an academic degree in art history. This statement says a lot about access to institutions, inclusion, and exclusion. How important was it for you and your work to be an academically trained art historian?

JUNGHAUS: Yes. This Wikipedia article presents me as a singular example, but that in itself reflects how stereotypes operate – Roma are often framed as isolated exceptions. In reality, there are many outstanding Roma art historians and cultural leaders, such as Dr. Jana Horváthová, director of the Brno Museum of Romani Culture, and Miguel Ángel Vargas, curator at Factoría Cultural in Seville. My activism has always centered on securing space and funding for Roma artists, confronting systemic discrimination, and ensuring Roma artists’ inclusion in major exhibitions. This work requires not only advocacy but also meeting the competitive standards expected both by mainstream institutions and by the academic sphere – because without institutional recognition, the fight for visibility and legitimacy remains an uphill battle. My work is an intervention, a reclamation of agency, ensuring that Roma and Roma art history are defined by authentic voices. To amplify this impact, I seek to connect with other practitioners and with colleagues who share this approach, strengthening our collective practice and reach.

DOGRAMACI: What you refer to is working in communities and in kinships. I think that was very visible in the 2022 Polish pavilion. In the 120-year history of the Venice Art Biennale, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas was the first Roma to be the representative artist of a national pavilion. The project “Re-enchanting the World” referred to the astrological frescoes of the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara and adapted their themes and iconographies for a Roma art history. Palazzo Schifanoia was central to the concept of the Nachleben, the afterlife developed by the cultural theorist Aby Warburg at the beginning of the 20th century. In this way, a path leads from Warburg to you – because you are portrayed in the center section of Mirga-Tas’s “Re-enchanting the World” as one of many important female reference figures for her.

JUNGHAUS: When we entered the pavilion, which showcased the work of Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, the experience was profoundly moving. Together with the artist, and with Ethel Brooks, the artist Daniel Baker, and Joanna Warsza, who was one of the cocurators of the exhibition, we traveled there with 100 people from the Sinti and Roma community of Venice Mestre. The trip was fun and loud, but when we crossed the pavilion’s threshold, a silence, rich with emotion, settled over the space as we stood mesmerized by the work. We all worked toward this goal, but even we were surprised to see Roma art and Roma individuals not as a peripheral subject but at the center of the contemporary art discourse. I see this as a true example for decolonizing narratives, our art history, and our minds …

DOGRAMACI: The power of different voices it very much needed in times when the political far right is successful in Europe and beyond. Could you consider the impact of these developments on the work, for example, of ERIAC or on your own work? And on the other side, how important is ERIAC’s work today in these very difficult times of political pressure and uncertainty?

JUNGHAUS: All of us in the cultural field feel the impact of the rising far right. For ERIAC and for my own work, you can see the opportunities shrinking by the day. Roma are visible if they pay for space and infrastructure, and I don’t have to explain how terribly unfair and unjust this is and how destructive these exclusionary mechanisms are for our democracies. How the art scene rejects Roma is a vicious circle. They say, “This is ethnic art. You should ask for your own museums and your own spaces from governments.” But when we go to the government to ask for our own spaces, we are rejected because that would be a cultural ghetto. Many minority communities – not just Roma – find themselves trapped in an insurmountable cycle, navigating a labyrinth of structural limitations: of funding, institutional access, infrastructure, and opportunity. Yet, despite my deep pessimism about the present, I hold an unwavering optimism for the future. I believe in our capacity to be conscious of the fragility of our democracy and in art’s enduring influence on generations to come. I trust that many curators, directors, and cultural leaders remain committed to critically reassessing their institutions, forging deeper connections with local communities, and recognizing that Roma continue to shape European culture at the highest level.

Charly Bechaimont, “We Never Made the War,” 2023

DOGRAMACI: Let’s end the conversation with a view into the future and the dream of futures. So, my very last question is: What would you like to see in the future? RomaMoMA or Roma art and artists in every art institution? Maybe there’s no either-or.

JUNGHAUS: It isn’t a known fact that there are over 30,000 Roma artworks in state collections around Europe. And there is a repository of beautiful archives in multiple locations as well. It would be entirely possible to weave together a cultural history substantial enough to establish a RomaMoMA – an institution that would not only archive but also assert Roma artistic and intellectual presence. To witness its realization within my lifetime remains a profound wish. Yet, as the far right gains momentum, this vision feels increasingly fragile, its contours fading against the tide of exclusion. Still, my hope endures. I place my faith in the coming generations and in the creative force of Roma artists whose work redefines the boundaries of contemporary culture. A RomaMoMA would not merely be a museum; it would be a site of dynamic exchange, where dialogue with majority communities takes shape, where solidarities are forged across peripheral landscapes, and where art – our art – claims its rightful space in history.

Burcu Dogramaci is a professor of art history at Ludwig Maximilian University Munich and director of the Käte Hamburger Research Centre “global dis:connect”. Her research areas are modern and contemporary art, with a focus on exile, migration, and flight, as well as photography, architecture, textile, fashion, and live art. She was the PI of the ERC Consolidator Project “Relocating Modernism: Global Metropolises, Modern Art and Exile (METROMOD)” (2017–2023).

Timea Junghaus is an art historian, a leader of the Roma cultural and political movement, and a contemporary art curator. She is the executive director of the Berlin-based European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture (ERIAC), founded by the Council of Europe, the Open Society Foundations, and the Alliance for the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture. She has researched and published extensively on the conjunctions of modern and contemporary art with critical theory, with particular reference to issues of cultural difference, colonialism, and minority representation. She was the curator of “Paradise Lost” – the First Roma Pavilion, at the 52nd Venice Biennale. As the leading European organization in Roma arts and culture, ERIAC has presented Roma art at the world’s most prestigious art events under Junghaus’s leadership since 2017.

Image credits: 1. Courtesy Charly Bechaimont, photo Eva Djen; 2. © Selma Selman; 3. © Västerås Konstmuseum Sweden, courtesy Małgorzata Mirga-Tas and a private collection; 4. Courtesy Emília Rigová, photo Zuzana Pustaiová; 5. Courtesy Robert Gabris, photo Vlado Elias; 6. Courtesy of OMARA Mara Oláh, Everybody Needs Art and Longtermhandstand, Budapest; 7. Courtesy Selma Selman, photo Damir Šagolj, 8. Courtesy Charly Bechaimont, photo Roberto Marossi