Partially captured Dan Ward on Moyra Davey’s “Index Cards”

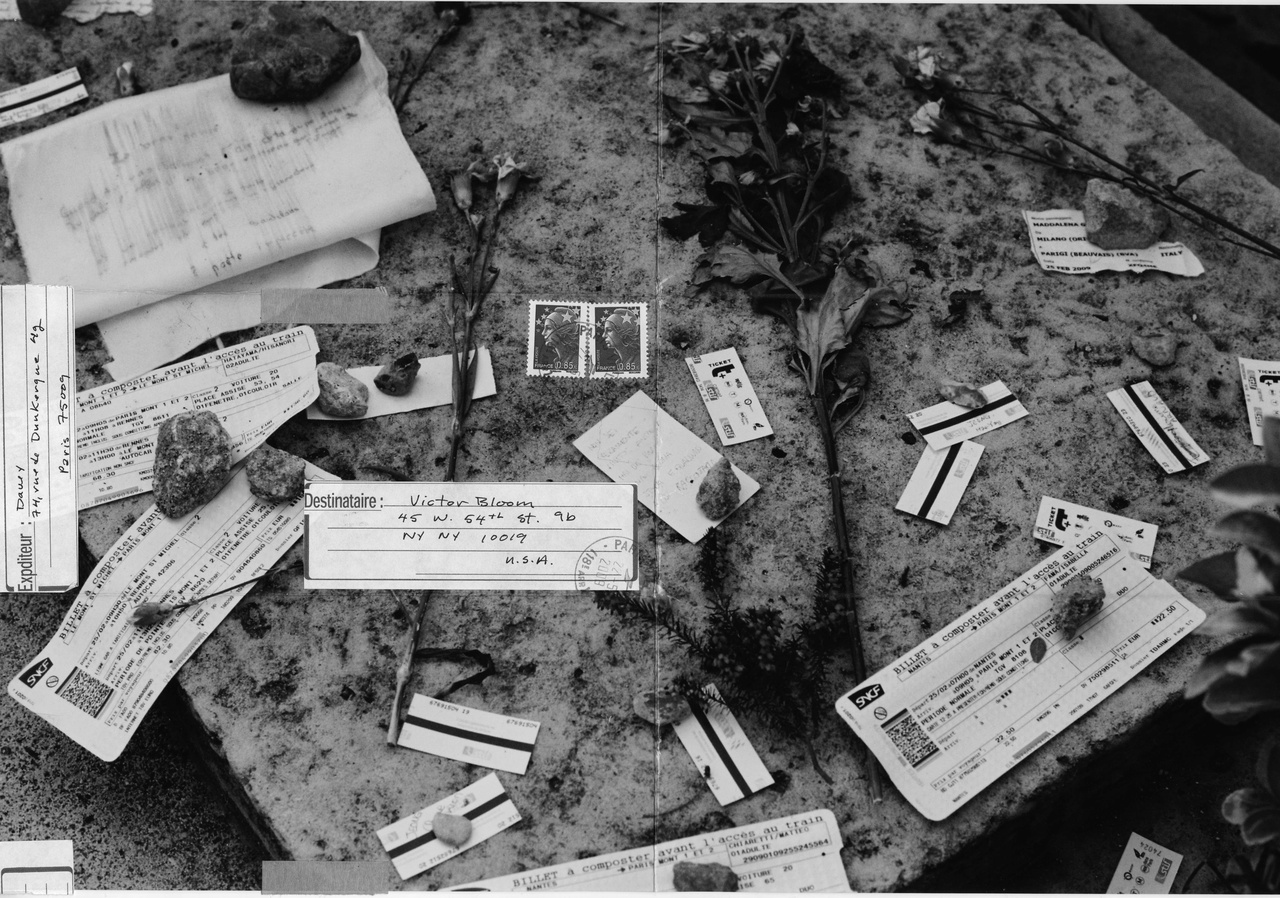

Moyra Davey, Charles Baudelaire`s grave at Montparnasse cemetery, Paris, 2009

Moyra Davey’s Index Cards (2020) collects 15 texts: a mix of notes, film scripts, and short essays written between 2003 and 2019, a by-product of her work as an artist as much as a writing with its own internal logic. Published in Europe by Fitzcarraldo Editions and in the US by New Directions, it is a conventional writing of familiar names and subjects: a diary; a memoir; an essay film diagram concerned with photography, writer’s block, Walter Benjamin, motherhood, Chantal Akerman, illness, reading, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Jean Genet. If Davey’s films could be understood as a ‘cinema haunted by writing,’ [1] to use Serge Daney’s expression, her writing here is haunted by imagery and asymmetric correspondence. Pictures are inscribed, visual processes written, mundane details catalogued. These differing categories, however, are not blurred or deconstructed to produce new arrangements, but rather kept whole in order to elaborate and contrast the tendencies of form. Unlike Davey’s earlier publications Burn the Diaries (2014) and Les Goddesses / Hemlock Forest (2017), printed in colour on coated paper and which are closer to the photo-essay (as well as an extension or substitute for an exhibition), this collection is divorced from photography and video save for small black and white reproductions placed within, and at the conclusion of, specific sections. Without this visual scaffolding, the texts appear as journal entries combined with a kind of ongoing taxonomy of artworks, artists, and thinkers. It is a self-consciously fragmentary form that attempts to suture together the anxieties of obsessive, personal reflection with an equally repetitive encircling of aesthetic and philosophical thought; Davey’s tendency to extract phrases from a particular context and enter them into exchange with that of a different but mirrored shape via narration is central to the continuity and attitude of the work. As Davey herself says: “I realize that I write about being deformed and remade by the things I read. And I am trying to write in the form of the things that I want to read: diaries, fragments, lists” (p. 97). Writing about Elena Ferrante, Karl Ove Knausgård, and Hervé Guibert, she adds: “They are long-take writers. They circle back over the material again and again each time refracted through a slightly altered prism. There is comfort in their repetition” (p. 217).

Several quotations are repeated throughout like incantations, fusing aphorism with interpretation. The first: “A disappointed woman should try to construct happiness out of a set of materials within her reach,” by the English anarchist, and husband to Wollstonecraft, William Godwin. Another by Akerman – “…the more particular I am, the more I address the general,” with a similar variation by Rainer Werner Fassbinder; others by the likes of Benjamin (via Charles Baudelaire): “l'atelier qui chante et qui bavarde,” roughly translated as “the workshop that sings and chats.” These quotes and others appear incessantly, circling the same ‘personal pantheon’ and familiar modernist canon. It is as if through devout recital their meaning will open and provide historical precision and clarity to imprecise expressions. Or as Davey puts it: “I am reliant on the words of others, and I glom on to the dead” (p. 188).

Similar to her photographic series Copperheads (1990) and Subway Writers (2011), each line is economic and epistolary, with sub-headings like “FEAR,” “11 June,” “TAUTOLOGY,” and “JAMES BALDWIN,” compiling incomplete, disjointed thoughts for the reader to trace. This combination (quote and confession) act as a primer for Davey’s work in general, as subjects are obsessively turned over and examined — not to employ each reference in the production of new theoretical formations in an academic sense, but rather to test their acuity and force outside of those hermetic discussions. As an effect, this also produces a secondary appraisal of a general discourse that occurs within contemporary art networks — often hard to plot — such as recounting in “Caryatids & Promiscuity” the “correct, critical model” (p. 144) for photography in the 1980s and early 1990s, exemplified by Martha Rosler’s Bowery series (1974-75), positing that this position is “…now a historical footnote, largely ignored by younger generations who are having nothing of those withholding attitudes toward visual pleasures. The camera is everywhere…” (p. 146). These models are compared, weighed, and updated, a praxis of criticism that takes place in association. And yet, through rousing these names and figures, the gentle fragility of reflection is fastened to the stability of a canon. Or in other words, there is a tendency to speak of the already branded, the already metabolised. Davey writes: “I’m piecing together fragments because I don’t yet have a subject” (p. 182), but the absent, buried subject might simultaneously be nostalgia for a long impossible fragment: “I begin to wonder if it’s not just the modernist paradigm kicking in, that a metadiscourse is always more satisfying: painting about painting, photographs about photography, writing about writing” (p. 45).

This back and forth between reflection (often on the labour and networks of art) and theoretical reading forms a circuit and elaborates a broader methodology as early media-specific inquiries into photography and reading are incorporated into formal process, intermittently returning like interruptions: “I already had a script, but as I began to perform it for the camera the narrative about picture-taking became more and more insistent” (p. 144). This trace of an absent form appears not only as a subject, but via ‘mistakes’ approximating the original narration, e.g. “… [narrator forgets her lines, begins again from the top]” (p. 9). The early Fifty Minutes and more recent Hemlock Forest both include such markings, these close textual copies exemplifying the centrality within Davey’s work of the unstable “I” of the narrator’s voice and the interruption or displacement she is able to delicately construct by moving between subjects and processes of record/inscription. However, here this process of estrangement remains only an estimation, while it is far more evident in video where, for example, scripts are recited from an iPhone recording, and cameras, headphones, and tripods frequently appear in the frame (documenting books, letters, photographs, bodies), as if to assert the terrifying accountancy of representation and thought as they ricochet across material procedures, only ever partially captured.

“Index,” then, beyond the allusion to note-taking or the indexicality of photography, could be understood as a process of approximating incommensurate forms of measurement (image, word, body). Quotations are collected and re-written, photographs are returned to many years later — thoughts recorded as both an act of interpretation and an inscription to later exhume. And through this exhaustive notation, reflection, and (re-)citation, and in applying these differing but orthodox processes to each other — text to image, theory to diary, biography to history — Davey moulds these materials on to a fractured subjective experience and brings the dead theories and figures of ‘High Art’ from their disembodied ideal into the grubby contradictions of the living. Yet within this labour of reassembling and bringing together what has been separated is a paradoxical reassurance over the relation between “art and life” (as the book’s back cover names it). A kind of modernist melancholy, a reconciliation only possible via Romantic ideas of living and art-making: e.g., the sublime, the canon, individual interpretation, minor rebellion. A position Davey can only embrace.

Dan Ward is an artist and writer based in London.

Image Credit: New Directions, Moyra Davey

Notes

| [1] | Serge Daney, “Les Cahiers du Cinéma 1968–1977: Interview with Serge Daney,” interview by T. L. French, The Thousand Eyes, no. 2 (1977), p. 31. |