Slow Return By Derrais Carter

preparing for black revelry

“Even in apocalyptic times, when words scarcely even mean anymore, they matter.” [1]

As I write this, quarantine gives me a context for surrendering … to slowness. It provides a backdrop for embracing a drawn-out, low, expansive tone. A quiet pace. This feeling is not new to me, but the intensity is. Because — in isolation, grief. In isolation, depression. In isolation, hunger for intimacy. In isolation, need. In isolation, suffering. In isolation, work. I steal time to create relief. A roguish relation to standardized temporalities allows me to tend to myself and my loved ones. And that tending, along with the consideration that it requires, is always ensconced in socio-political crisis. The urgency remains. So, I go slow. I return.

While reading a recently published essay by ARTS.BLACK co-founder Jessica Lynne, [2] I search, unknowingly, for a remembrance of my southernness. For months, it has felt so distant, beyond the orbit of my want. Lynne’s exploration/honoring of black southern queer intimacy and photography envelops me in an interval of longing. Her reading of two photographs attends to black queer southern life in a way that compellingly undermines the strategies many scholars employ to assign historical meaning and relevance to visual texts. Riffing on Tina Campt, Lynne listens to photographs.

Through her prose, a slowness manifests in me. My body remembers southern sprawls, lush fields, humid sunsets, sweat rags, red clay, lightning bugs, and gravel roads. Although I read in repose, my left hand and forearm brace as they recall bravely probing and swishing through coolers, reaching through layers of ice and frigid water for liquid relief. This is a prayer. Lynne concludes:

“If I look at each photograph and listen closely, it is possible to imagine each pair as a version of the other with time marvelously compressed and then decompressed. Maybe this, then, is part of that which is Black and Queer and Southern. To be in and out of time. To be illegible to most. Our lives, captured, become their own texts, an insistent language that only becomes legible if we truly know how to see.” [3]

For months, I had barely read anything in full. Couldn’t bring myself to work more aggressively than usual to compensate for the pandemic malaise. But the title of Lynne’s piece drew me in: “That Which We are Still Learning to Name.” Fittingly, I can’t concretely explain how this sends me elsewhere, somewhere private. And I won’t explain how it enables necessary returns or how it produces relief within me. Just trust and believe.

For the last three years, poet Nicole Sealey has encouraged people to read 31 poetry volumes and/or chapbooks throughout the month of August. This initiative, dubbed #thesealeychallenge, is for Sealey, and many others, a return to reading. It is also, perhaps, an exercise in worldmaking. You surround yourself with and immerse yourself in the words and imaginations of poets, each volume adding another layer to your augmented reality. This year, I failed the challenge before I could begin.

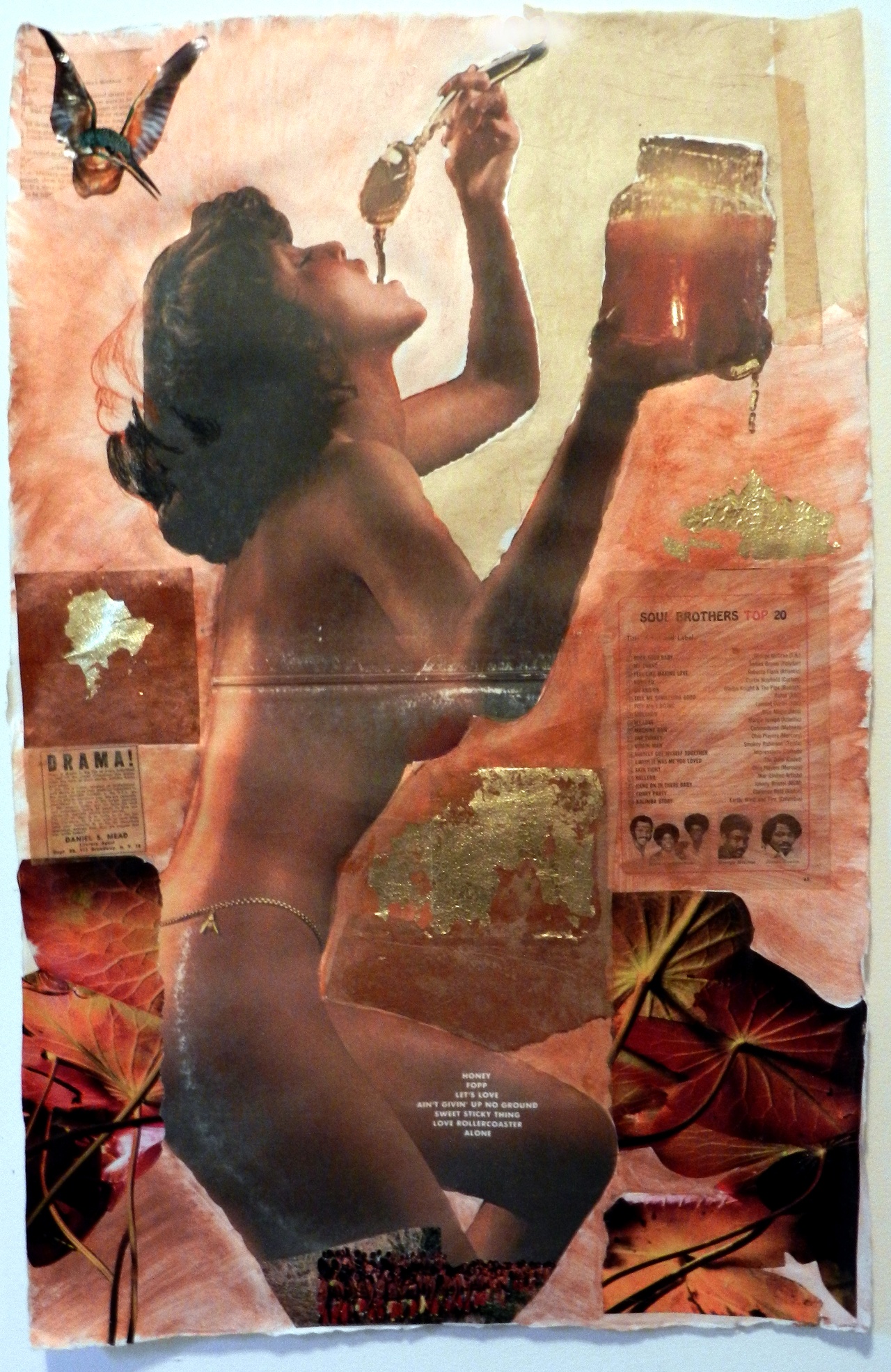

As I followed the online posts of the active participants, I thought about the poets whose work has produced in me a deep and abiding knowledge that this world ain’t the only one. I remembered how reading Alison C. Rollins’ Library of Small Catastrophes (2019) alongside sidony o’neal’s f a c e bowl (2013) shortened my breath. I yearned for greater sensory access to the aromas gorgeously orchestrated by S*an D. Henry-Smith and Imani Elizabeth Jackson in Consider the Tongue (2019). I would stare beyond the buildings and insist on visualizing the beautiful oceanic expanse conjured by Alexis Gumbs’ M Archive: After the End of the World (2018). Or wade in the warm honey of Krista Franklin’s Too Much Midnight (2020), buoyed by the thick bass of an Ohio Players track. I’m drawn to poetry that instigates and fuels desires for worlds made of seditious laughter and memories that feel impossibly mine. Which is to say, I’m drawn to poetry that apprehends me, that quakes my spirit and warms my flesh. This is work that keeps me in my body. Keeps me attentive. Keeps me slow.

"Oshun as Ohio Player(s)" by Krista Franklin

In quarantine, nothing I write feels sufficient. There aren’t many words I can offer that feel fitting for “these times.” Yet, with the dread and orneriness I faithfully carry with me, I return to the line opening this essay:

Even in apocalyptic times, when words scarcely even mean anymore, they matter.

After months of languishing in isolation, I left the searing desert heat of the place I tried to call home. I fled the city with the constricting air and the rumors about black people being hunted. This was the place where I was forced to grieve, to wail and scream the agony of my loss. I grabbed whatever I hadn’t stored or sold so that I wouldn’t have to sob about the distance and danger preventing me from holding loved ones and making sure they had the tangible support they needed. No card could communicate it. Phone calls would only do so much.

In grief, one thing became abundantly clear. The desert is not my home.

This writing takes shape as I drive home to Kansas City. So far, every stop along the way feels like it could be the last. Yet, and still, hugging my little sister, running errands for my 90-year old grandfather, swapping stories with my Pops, and playing Scrabble with my stepmom are the balm I need for a wound that doesn’t want to close.

So, I don’t know. When I hear “new normal” it conjures in me a revulsion that is centuries-old. And rather than rush towards an optimistic and delusional “new” which is subtended by mundane and spectacular anti-black violence, I will be right here … going slow.

Derrais Carter is a writer, artist, and cognac sipper. He is currently completing a few projects that may or may not see the light of day in the next year.

Image Credit: Derrais Carter

Notes

| [1] | Samiya Bashir, “Letter From Exile: Finding Home in a Pandemic,” Lithub, July 23, 2020, https://lithub.com/letter-from-exile-finding-home-in-a-pandemic/. |

| [2] | Jessica Lynne, “ ‘That Which We Are Still Learning to Name’: Two Photographs of Black Queer Intimacy,” Southern Cultures, vol. 26, no. 2 (Summer 2020), pp. 150-157. |

| [3] | Ibid., p. 157. |