Pose, Position, Positionality by Nicholas Gamso

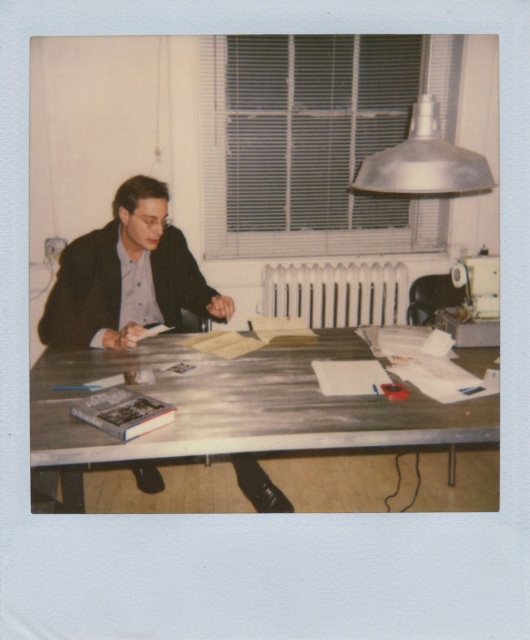

Craig Owens in Barbara Kruger’s loft, New York, 1988

Craig Owens, the art historian and queer theorist, died of complications from AIDS thirty years ago this summer. He is remembered as a romantic figure of the 1980s theory world, having written some of the first pieces of American art criticism that referred to the works of Jean-François Lyotard and Jacques Derrida. Theory offered Owens a bridge between art and its social contexts, prompting him to explore topics such as gender, sexuality, and national politics, as well as his own role as a critic and academic. He ultimately came to view his work as a “continuous self-questioning”: the point was not an “existentialist ‘who am I,’ but an inquiry into the self as constructed and positioned.” [1]

There is much to say about how Owens’ own life shaped this reflexive way of thinking. Certainly, his experience as a gay man set him on the periphery of a homophobic society, even as it granted him occasional privilege. As a child in rural Pennsylvania, he was forced to develop social aptitude and independence, driven by a will to escape what he saw as an alienating, provincial existence: “Most of my relatives on my mother’s side had either been farmers or coal miners,” he said in a 1984 interview with Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield. “There were very, very few people around with whom I had any sense of shared interests. Basically, I just wanted to leave that community.” [2] Owens’ flight from a space of deprivation and solitude into the worldliness of queer intellectual life was one of sudden exposure to power. After a stint in theater, he began writing about art, becoming an editor at Skyline and Art in America, and enrolling at CUNY to study with Rosalind Krauss, the influential art critic who co-founded October (with Annette Michelson) in 1977.

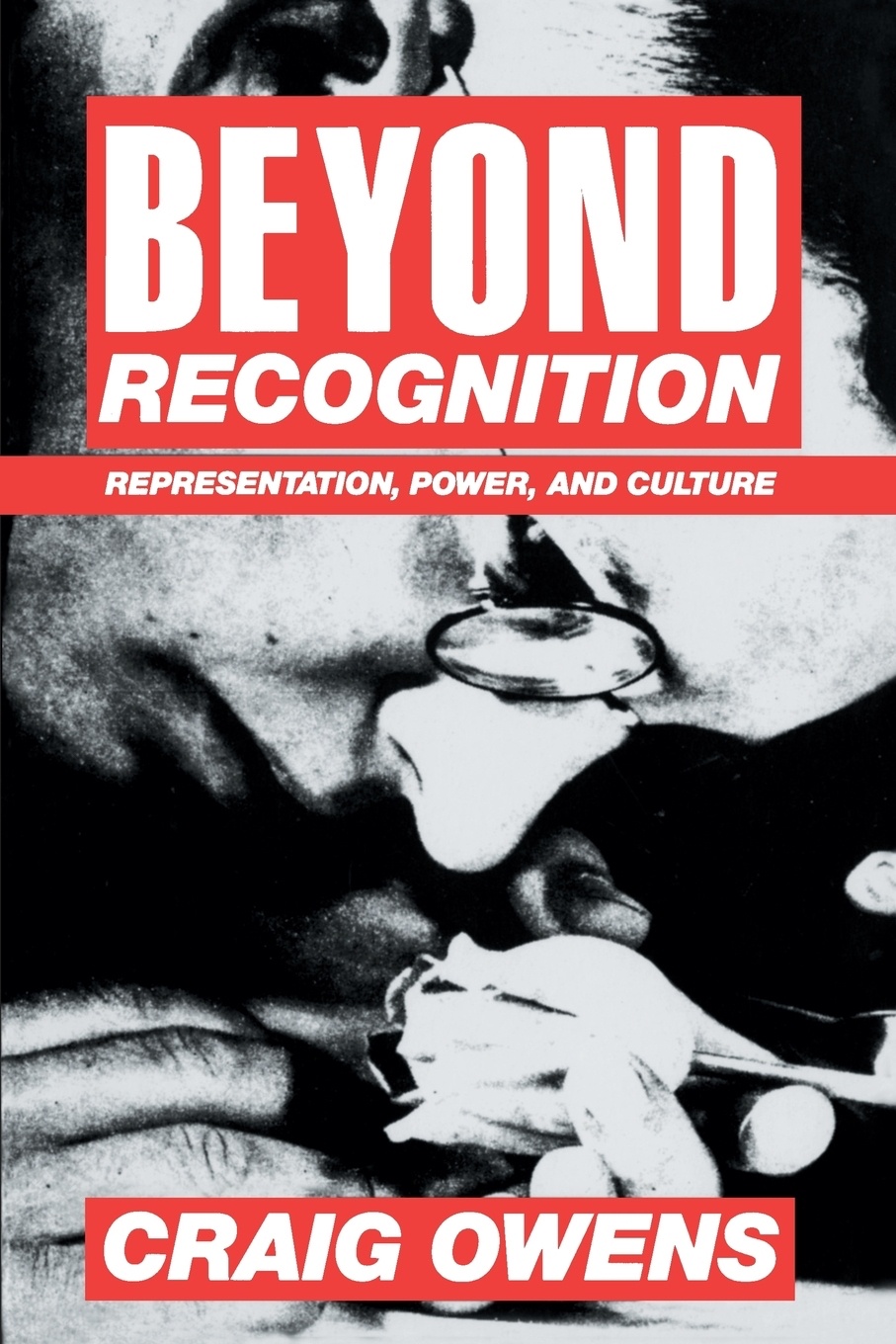

"Beyond Recognition," a collection of writings by Craig Owens, published by University of California Press in 1994. Edited by Scott Bryson, Barbara Kruger, Lynne Tillman, and Jane Weinstock with an introduction by Simon Watney.

“I was most fascinated by that which excluded me most – my own attraction to the narcissistic,” Owens later admitted, recalling his introduction to this elite mien. He felt he had no choice but to consolidate an image of himself, what he called, with some embarrassment, his “Craig Owens act.” It wasn’t an original persona, but a composite, informed by what had taken place around him. In his early essay “The Allegorical Impulse” (published in two parts in October) he describes this kind of self-fashioning through the language of allegory: it is “synthetic,” “fragmentary,” “imperfect,” “incomplete.” The critic becomes the ultimate allegorist, “lays claim to the culturally significant, poses as its interpreter.” [3]

Inventing such a persona would also mean sequestering power. For Owens, this occurred in 1979, when artist Donald Newman gave his new show at New York’s independent Artists Space gallery the astonishing title “The N—Drawings,” eliciting widespread condemnation. (The title apparently alludes to Newman, a white artist, smearing his face with charcoal.) Owens was one of several writers (including Krauss) who defended the artist: “The cry went up ‘Racism!’ –as if the mere use of a word, and not the context in which it occurs, determines meaning.” He went so far as to appropriate the epithet to describe himself and other figures at the supposed edge of the art world: “The artists who show at Artists Space and avail themselves of its services have been denied access to the commercial gallery and museum power structure. In a sense, they are all ‘n—s.’” [4]

This sentence is excruciating to recall. The use of appropriation and parody makes no effort, has no patience for moral purpose. Racial difference was simply another mutable, generic trope to be allegorized toward whatever purpose—here to describe minor oppositions within the art economy. As critic Aruna D’Souza put it, Owens saw Artists Space “as a place that defended culture against the ruling power of art institutions, including the art market.” But Owens had forgotten, according to D’Souza, “who actually held the power.” [5]

When Owens went on to write about feminism, he tried to make sense of such pedantic displays – to reckon with the ways that allegory might affirm, rather than disrupt, the cruelties of dominant society. He cites collage artist Barbara Kruger’s remark on the listlessness of the socialized mind: “We loiter outside of trade and speech and are obliged to steal language.” [6] Owens would later attribute an epiphany to Kruger’s deconstructive collage strategies: “my encounter with Barbara’s work, and writing about it, enabled me to reflect on some issues about who I was and maybe, more specifically, whom I was posing as.” [7]

In this shift – from positive to rhetorical modes – we can see the outlines of what I want to call queer worldliness, an ease of motion realized in the mix of social and professional spheres that comprise urban cultural economies. Such facility arises from queer people’s displacement from the normative public sphere and movement about the urban wilds, where sex, art, and other forms of affinity combine. The idea is exemplified by figures like Owens’ friend, the curator and art historian Douglas Crimp (another Krauss progeny), who as a recent profile in the Paris Review put it, “would enter Max’s Kansas City and greet the arguing elite of minimalist art on his way to the back, where he could party with the drag queens of Warhol’s Factory.” [8] This kind of acumen can move worlds and structure relationships. But there is a critical version of queer worldliness too: ambivalence over what such a life may reveal.

Owens’ traversal of social environments gave him mordant insight into the inequities of the art system. He came to question artists and intellectuals who had, in his words, “only partially withdrawn from the middle-class elite,” to become “brokers between the culture industry and subculture.” [9] So did he question his own dexterity, refuting the myth of “gay monopolists” – Luce Irigaray’s term for gay men’s intrusions into feminism and supposed control over social discourse. Owens referred to Irigaray’s remark as “patently homophobic,” arguing that such a charge was a form of scapegoating, especially during the Reaganite culture wars and the unmitigated spread of AIDS across urban America. [10] Engagement with others’ concerns did not have to be parasitic, even if it sometimes could be. Often it was a matter of need, position – where you live, where you were born, how you are perceived even by your nominal allies, what kind of a world you inhabit.

It is hard to disagree with this assessment. Clearly Owens’ tragic death, at the age of 39, put the matter of his own subjugation into relief. It occurred simultaneously with thousands of other deaths from AIDS – not in a neutral space but in a shared political context. We may thus remember Owens less through his singular, personal achievements than by way of his encounters with others in a changing world. His legacy remains as part of what Eve Sedgwick describes, in her 1990 elegy, as a “citational network” of disembodied referents, residing as memory, as trace, as sign in the matrix of relations we all inhabit. [11]

Nicholas Gamso teaches at the San Francisco Art Institute.

Image Credit: Barbara Kruger, UC Press

Notes

| [1] | Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield, “Craig Owens: an Interview” (1984). Part of their Art and Artists series for the Video Data Bank. The interview was recently published as Portrait of a Young Critic (New York: Badlands Unlimited, 2018). |

| [2] | Ibid. |

| [3] | Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” in October 12 (Spring 1980). |

| [4] | Craig Owens, “Black and White,” in Skyline (April 1979). |

| [5] | Shiv Kotecha, “Who Has The Power: A Conversation With Aruna D’Souza,” in Art in America (May 2, 2018). |

| [6] | Craig Owens, “Posing,” in Difference: On Representation and Sexuality, ed. Kate Linker (New York: New Museum, 1984). |

| [7] | Blumenthal and Horsfield. |

| [8] | Sarah Cowen, “Before Pictures: An Interview with Douglas Crimp,” Paris Review Online, November 8, 2016, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2016/11/08/pictures-interview-douglas-crimp/. |

| [9] | Craig Owens, “Commentary: The Problem with Puerilism,” in Art in America, vol. 72, no. 6 (Summer 1984). |

| [10] | Craig Owens, “Outlaws: Gay Men and Feminism,” in Men in Feminism, eds. Alice Jardine and Paul Smith (New York: Methuen, 1987). |

| [11] | Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Memorial for Craig Owens,” Tendencies (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1993). |