RETURN POLICIES María Minera on Early Memories and Recent Reappearances of Santiago Sierra in Mexico City

Santiago Sierra, “Obstruction of a Freeway With a Truck’s Trailer,” 1998

The 1990s marked a special time for Mexico City’s local art scene, displaying an unprecedented inventiveness that hasn’t returned since. It was one of those rare moments in history when the market is caught looking off in another direction (in this case, toward the derivative, neo-Mexicanist paintings collectors like so much and that are, coincidentally, having a revival these days). There were practically zero galleries dedicated to showing post-conceptual art; while visible and well marketed in other latitudes, it was still marginalized here – until the turn of the century, when it suddenly emerged and gained traction. Hence, this was a rather brief period in which every new exhibit or new work presupposed a happening for the small community that gathered to see it, mostly in apartments and converted industrial and commercial spaces, such as the old bakery that famously became La Panadería, a place run by the artists Miguel Calderón and Yoshua Okón. Amidst many new projects and practices, the work of a young artist from Madrid, Santiago Sierra, stood out due to its bold polemics.

Particularly memorable for me and certainly also for other locals is one November afternoon in 1998, when – with one of his typical gestures and an almost Biblical tone – Sierra “caused the sea to go back, and made the sea dry land, and the waters were divided.” The tide he held back was one of automobiles, traveling their daily route along one of the most congested arteries in the world, Mexico City’s so-called Periférico, or beltway, at rush hour. And instead of using his hand, like Moses, Sierra resorted to a huge tractor trailer that, sidetracked from its original function of transporting juice cans, [1] played the transient role of massive sculpture. It was no coincidence that he chose this particular time and place for the work, which was to go down in art history under the title Obstruction of a Freeway with a Truck’s Trailer (1998). Not only was it an especially busy thoroughfare, it was also a pathway already lined by artistic endeavors: back in 1968, the fast lane had been transformed into a cultural corridor and dubbed the Ruta de la Amistad (Route of Friendship) to celebrate the controversial Olympic Games the city hosted that year. [2] Ever since, the stretch has been home to a roster of modernist sculptures by a variety of international artists. Sierra’s piece was his way of contributing, albeit fleetingly, to the conversation, conducted intensively in many cities around the world during those years, regarding the place and function of public art.

The trailer cut off traffic for six minutes, leaving one side of the freeway oddly deserted while transforming the other into a surge of cars, longer and mightier with every minute, with furious drivers behind the wheel. It was a kind of open wound in the daily flow of commodities and commuters, and at the same time, a way of contesting, with great daring, the minimalist tradition of large-scale sculpture. The form that emerged amidst a sea of automobiles, in a city whose breakneck pace and growth had, up until then, seemed unstoppable, was a rectangular prism that evoked Donald Judd’s sculptural pieces.

Santiago Sierra, “Hooded Woman Seated Facing the Wall,” 2003

Sierra had relocated to Mexico City in 1996. In an apartment located in the downtown district, he had opened one of the alternative exhibition spaces that characterized the still relatively underground culture of the time. A considerable number of emerging artists got their start on the vibrant third floor of 51 Regina Street. It was also where Sierra himself, after attempting to hoist a car parked down on the street with a rope from inside the apartment, started a series of works that would put an end to his almost formalist beginnings, and set off his uncompromising critique of the governing economic system with its utter lack of humanity and, specifically, its exploitation of individual labor.

For the first iteration of his now-famous Tattoo Line series, he looked for a person with no tattoos, who had no intention of being tattooed, but would – due to a precarious situation and upon payment of 50 pesos (roughly equivalent to 2.75 euros today) – consent to bearing a vertical line on his back for life. Other “subjects” would follow. The piece was at once an ephemeral action (except for those who would bear a lasting vertical line on their backs) and a series of photographs that acted more or less as a registry. From here on out, on countless occasions, Sierra would explore the idea of minimally remunerating individuals or groups for carrying out some kind of arbitrary labor. For example, in the Museo Tamayo in 1999, he paid 460 people to remain standing for three hours during an inauguration. From the start, Sierra’s work with clearly needy people from outside the art world was polemic and highly controversial: after all, he employed the means of the system that he himself criticized. In other words, he used precarious workers in order to shed light on precariousness and exploited individuals from outside the art community to remind its insiders (to whom the actions were mainly addressed) that the “real” world was a dreadful place. But somehow, he succeeded – not by changing one iota the situation of the exploitation of man by man, of course, but rather by raising the art world’s critical, sociopolitical awareness – an awareness it still bears, albeit in an increasingly forced and marketable manner.

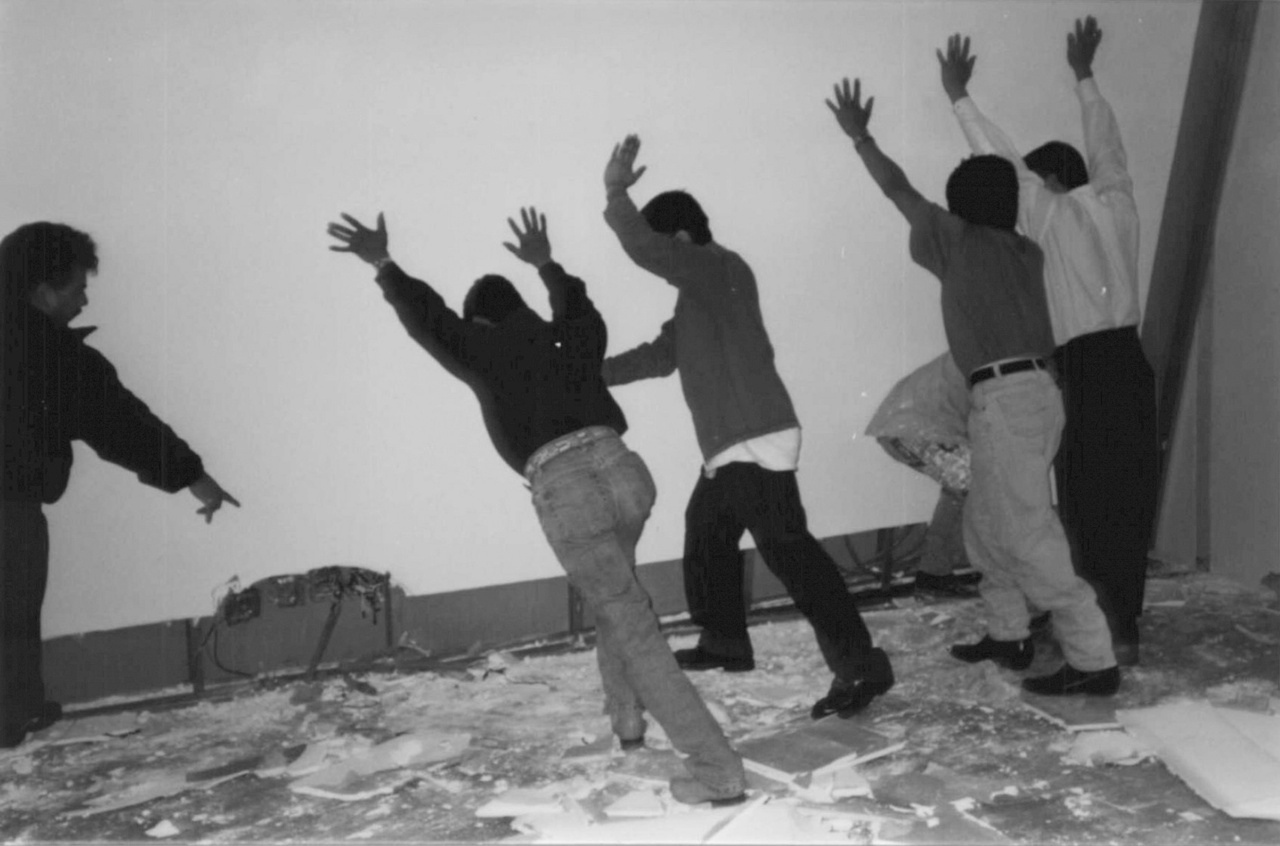

Santiago Sierra, “The Wall of a Gallery Pulled Out, Inclined 60 Degrees from the Ground and Sustained By 5 People,” 2000

I am wondering if Sierra’s stay in Mexico, a chronically underdeveloped nation, inspired this vein of reflection because cheap, or rather, dirt cheap labor is still common in non-regulated employment of all kinds around here. [3] At any rate, a sociopolitical approach that addresses exploitation strategies of global capitalism in connection with questions of mobility and migration would accompany the artist wherever he went. In 2003, for example, in Madrid, he hired 100 illegal immigrants and asked them to hide along Doctor Fourquet Street for four hours – to make them even more invisible and, at the same time, bring attention to their situation by asking the public to search for them. That same year, he had a wall erected around the Spanish pavilion in Venice and passport controls carried out at the main entrance to highlight the country’s isolationist policy.

For some time now, Sierra has been represented by Labor Gallery in Mexico City, which – judging by its name and program – appears to be pretty in tune with his earlier political work. He has exhibited here on several occasions over the past decade, remaining more or less true to himself and his approach. Currently, though, he is here to present something rather disconcerting: a series of photographs and drawings derived from a project commissioned by Balenciaga, a peculiar installation which served as a backdrop for the Spring/Summer 2023 runway show the brand presented at Paris Fashion Week in 2022. It is important to recall that in the year 2005, perhaps in an attempt to reconnect with his post-conceptual roots, Sierra presented the work House in Mud [4] at Kestner Gesellschaft in Hannover, where, echoing Walter de Maria’s famous Earth Rooms, he filled the entire space with mud. Not neatly, like his US colleague, but smearing the walls, creating a far more disturbing and definitely far muddier scene than de Maria’s well-groomed soil-clad rooms, one of which – The New York Earth Room (1977) is still on view today in a Soho apartment building. The images of Sierra’s intervention, those white walls spattered in brown, which evoke Richard Serra’s marvelous Splashings of molten lead, [5] have a certain charm, one that appears to go well with the radical chic Balenciaga likes to parade – not least through the label’s previous artist collaborations, like the particularly prominent and long-lasting one with Eliza Douglas and Anne Imhof. And so, the team behind the luxury brand, which has been part of the French Kering Group since 2001, invited Sierra to produce a similar panorama, albeit larger and far more elaborate – neatly soiled, one might say – to act as the scenario of a runway show that took place, comme il faut, in Paris.

Santiago Sierra, “House in Mud,” 2005

Presumably, Demna Gvasalia, Balenciaga’s creative director who is of Georgian origin and has described his life as a journey “from post-Communism to future couture,” [6] was also attracted by the political thrust of Sierras work. Having left behind a uniformed society where luxury barely existed, at least not officially, in order to design overpriced, sculptural garments – to Cristóbal Balenciaga’s taste – but using Velcro instead of buttons, Demna, as he is known in the trade, apparently found the perfect match in his attempt to make “subversive fashion” – as if such a thing were possible within a multinational business corporation. Visually as well, the tattered and distressed clothes that have become Balenciaga’s hallmark combined perfectly with the Mad Max effect Serra’s installation provided. But while back in Hannover the artist’s idea had been to “create a visual representation of the discomfort and anxiety associated with German history,” [7] his mud piece in Paris became part of Gvasalia’s brand strategy, a “metaphor for digging for the truth and being down to earth.” [8] And what could be more “down to earth” than a pair of ripped jeans – not ripped but in fact “super destroyed,” as they are described on Balenciaga’s site – with a 2,000-euro price tag?

Setting the stage for models dressed in futurist suits somewhere between military officer and rock musician, filth theatrically covering their shins every step of the way, Sierra’s mud-covered runway conveyed a grubby atmosphere that was also, it seems safe to say, strategically tailored to all those eager to dress fashionably – even if fashion means looking like Steven Tyler just got run over by a car. Of course, Sierra is one of many artists who have collaborated with fashion brands. But unlike Eva Jospin or Philippe Parreno, for example – who have worked with Dior and Louis Vuitton, respectively, or the aforementioned Balenciaga collaborators Anne Imhof and Eliza Douglas – he has made it his artistic mission to denounce the practices of this world-outside-the-world, where some of the richest men on the planet become still richer by selling allegedly used clothing, produced for low wages and often under inhumane conditions, in places very far removed from the runways of Paris. Sierra surely knows this very well.

Sierra, who is surely very aware of the fashion industry’s working conditions, was very influential during the years he lived here in Mexico City. Although he did not maintain close connections to the local scene after he left the city, many of us welcomed the radicality of his political work and followed his steps very closely, with appreciation. That’s why his recent return in the form of an exhibition based on his Balenciaga collaboration, is met with some disappointment. Instead of bold moves, such as stopping traffic or burning galleries [9] , he and his gallery decided to deliver uninteresting souvenirs of what Kim Kardashian saw from the front row: a project worlds away from his original Hannover concept and early political works, but in an ugly way connected with and immersed in the dirty dealings he once so trenchantly criticized.

María Minera (Mexico City, 1973) is an independent art writer. Since 1998 she has published reviews and essays in a variety of cultural magazines and media platforms. She has also contributed texts to numerous books, including *Eduardo Terrazas: Equilibrio múltiple (Red de museos, 2023), Appearance Stripped Bare: Desire and the Object in the Work of Marcel Duchamp and Jeff Koons, Even (Phaidon, 2019); Anni Albers (Tate, 2018); Silvia Gruner: Hemispheres; A Labyrinth Sketchbook (The Americas Society, 2017); Drawing: The Bottom Line (S.M.A.K, 2015); Damián Ortega: Casino (Mousse Publishing, 2015); Contemporary Art Mexico (TransGlobe Publishing, 2014); En esto ver aquello (Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes, 2014); and Gabriel Orozco: Natural Motion (Moderna Museet, 2013).

Translation: Tanya Huntington

Image credit: Courtesy of Santiago Sierra and KOW, Berlin

Notes

| [1] | Juice from the brand Jumex; at that time, the company was about to launch a contemporary art foundation that would eventually comprise one of the largest collections in Latin America. |

| [2] | It was inaugurated exactly ten days after the Tlatelolco massacre, a mass shooting by the Mexican Army and paramilitary groups of approximately 400 students during a protest over an incident of police repression that had taken place a few weeks earlier. |

| [3] | To give an impression, Mexico currently estimates a rate of informal employment of over 50 percent. |

| [4] | Translated into English as “House in Mud,” strangely enough, which undermines part of the irony of a “Smeared Institution,” the term we use in Spanish to refer to activities that imply corruption. |

| [5] | Like the one he presented at the Castelli Warehouse in 1968. |

| [6] | This borrows some words from an interview conducted by journalist Cathy Horyn. See System Magazine, no. 18 (Fall/Winter 2018). |

| [7] | A classic statement from the art world – in this case, taken from the Labor Gallery website – that manages to trivialize even the most sinister episodes in human history. |

| [8] | Said in an interview where, by the way, Sierra was not properly credited but rather mentioned in passing as just another “creative.” See Eric Brain, “Balenciaga Summer 2023 ‘The Mud Show’ Dared to Dig for the Truth Behind Fashion’s Vanity,” Hypebeast, October 2, 2022. |

| [9] | As in Gallery Burned with Gasoline (1997) at Galería Art Deposit, where Sierra scorched the walls and ceilings with torches. |