EVEN IF THIS CAN’T BE WITNESSED Max L. Feldman on Michelangelo Pistoletto at Castello di Rivoli, Turin

Michelangelo Pistoletto, “La mela reintegrata,” 2007–19

The phrase “many of one” could mean many things, or just one. It might have a straightforward political sense. In the case of, say, the traditional motto of the United States, e pluribus unum (Out of many, one), it can refer to how one stable community can emerge from the contributions of many different individuals (originally the slogan referred to the thirteen formerly British colonies; a generous interpretation makes it a general statement about pluralism). The phrase could just as equally have something to do with the philosophical problem of the “one and the many.” Certain debates in Western metaphysics since the pre-Socratics (Parmenides, Heraclitus), through the legacy of Plato and Aristotle, and recovered more recently by figures such as Gilles Deleuze and Alain Badiou, have centered on the nature of reality – whether Being is “one” (e.g. Pythagoras, Plotinus, Neoplatonic mysticism) or what Deleuze called an “assemblage” made up of many different parts.

In Michelangelo Pistoletto’s exhibition “Many of One” at Castello di Rivoli last autumn and winter, the two versions of the phrase are not only directly related but seem to interpenetrate each other. It’s there in the organization of the museum space, and it’s evident in the works themselves – at least when they’re read alongside the artist’s writings, including statements, manifestos, and speculative outpourings – since the late 1950s, all of which are as much a part of the works as the objects themselves. These are inspired by and continue arte povera pioneer Germano Celant’s aim to represent nature using the simplest materials. Celant wanted to reject industrial society in the name of infinite organic self-renewal, closely identifying our thoughts and feelings in the act of artistic creation, “re-inventing at every moment a new fantasy, pattern of behaviour, aestheticism, etc. of one’s own life [...] to live it as work.” [1]

Pistoletto’s version of this differs little from Celant’s. In this exhibition, however, many-of-oneness can be generously read as a loose, slightly new-agey take on what Deleuze meant by “multiplicity.” Following the ideas of Henri Bergson, Deleuze distinguished between two types of multiplicity found in the human experience of time: “discontinous” differences in degree that can be counted, and “vitual” differences in kind that are unquantifiable. [2] Pistoletto’s understanding of many-of-oneness, evident in his Mirror Paintings and sculptures, are a looser expression of virtual multiplicity. They extend the idea from being about how a viewer perceives a work of art in a specific place and time to the relation between the individual and the cosmos in general. Pistoletto’s approach packages all this in a freewheeling mixture of metaphysics and now-passé spiritually revolutionary optimism, written in charmingly vague, and often almost incomprehensible, esoteric jargon.

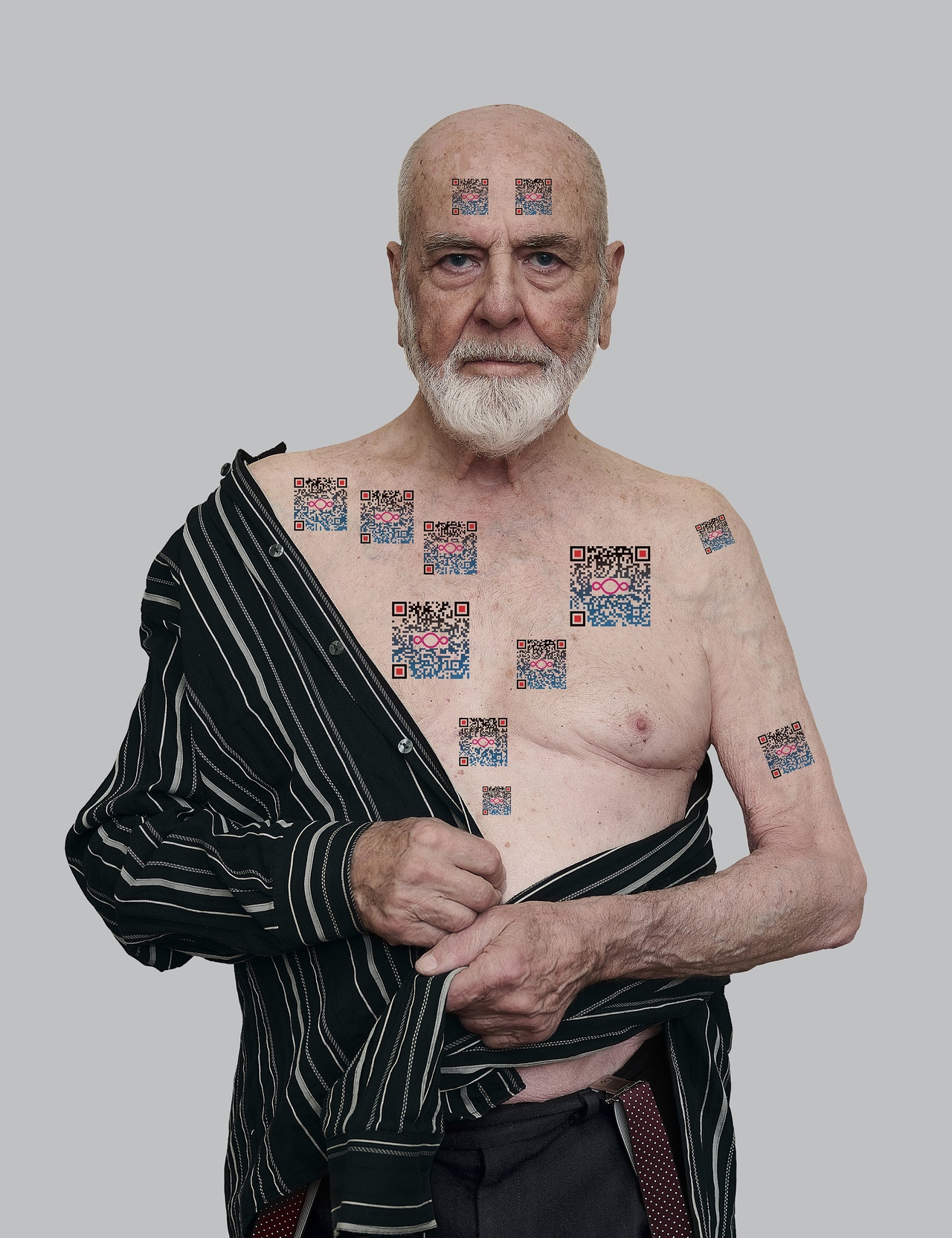

Michelangelo Pistoletto, “QR-Codes posession – Autoritratto,” 2019–23

The works in “Many of One” are housed in 29 open but interconnected skeletal wooden box-like structures. Each is named after an area of what the artist loosely thinks of as “human activity,” a way of categorizing many different skills, talents, or forms of expertise under one broad concept, thus including diverse categories such as “communication,” “nourishment,” and “cosmology,” as well as “urban planning” and “health.” The many-of-one structure is, meanwhile, a part of the works themselves.

This is especially true of Pistoletto’s Mirror Paintings series, whose classics here include Person: Art Sign (1976–2007) and In primo luogo (In the First Place, 1997). These objects, which the artist describes as the essential foundation of his practice, consist of a mirror with a figure either painted or printed on its surface (or a sculpture that appears in the reflection). This not only creates a two-way perspective that, apparently, overturns the tradition of image-making since the Renaissance, but also includes everything that we would usually think of as being “outside” the work (the viewer, other works in the space) in the picture plane. It thus becomes, as Pistoletto puts it, a “self-portrait of the world.” [3] In Deleuze’s surprisingly plainer terms, this amounts to one expression of what he calls a “time-image,” a succession of “de-chronologised moments” in which “the elements themselves are constantly changing with the relations of time in which they enter, and the terms with their connections.” [4]

In primo luogo, for example, consists of a gesso statue of a Roman senator placed in front of a huge mirror, appearing to hail himself as an equal. Virtual multiplicity, dechronologization, or many-of-oneness describes here how the work appears and what is included in it when it is on display. It applies equally when a viewer perceives it or if nobody is there at all, changing according to the space in which it is displayed, who and where the viewer is, what they look like, how they move their body, and the fact that time is constantly passing.

Also included is the possibility that one or more viewers may have seen the work displayed somewhere else – in a different place and time, at a different time in their own lives – to the extent that we’re barely able to say that the works are “here” in Castello di Rivoli, in some definitive, final form. Since what is included in the work will always change depending on where it is, there can be no such thing as the “one” stable version of the work. And there is an added difficulty in the case of Person: Art Sign, a gray painted figure facing backward, arms raised and legs spread to make a star-like shape. Not only is the work a constant work-in-progress, having been refined and redisplayed for 31 years; the fact that it is, in part, an imitation of Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing Vitruvian Man (c. 1490) suggests that the viewer’s knowledge and appreciation of this piece, and the humanistic ideal it is supposed to represent, are both included in the experience of seeing Person: Art Sign.

Pistoletto explains this with typically esoteric brio in his most recent manifesto, “Hominitheism and Demopraxy,” where he states that the mirror represents “the maximum extension of virtuality in the face of reality.” [5] Pistoletto is using “virtuality” in a different way to Deleuze, though perhaps, with some modifications, the two could still be compatible. His point has to do with the conventions of self-portraiture and what they reveal about personal identity. He means that self-portraiture tells us who the person is. It shows us a basic sight to be seen: the discrete existence and physical form of this human being at this time in their lives. But it also tells us who the individual really is on the inside, in their “soul.” The mirror radically extends this, allowing the artist’s self-portrait, which includes both the existence of a body in space and time and some immutable spiritual entity, to represent not just themselves, but everyone else in the world, including both those who are looking at it and those who aren’t but could.

How this applies when the figure is an imaginary Roman senator or a representation of the essence of a human being in general is, however, less easy to work out. Indeed, it really isn’t clear how we are to reconcile Pistoletto’s claims for his mirror paintings, which privilege the role of the artist, with what he says about a different type of his work: his Sign Art series. Person: Art Sign, problematically, contains elements of both. Indeed, sign art is, Pistoletto says, meant to extend the act of making signs – traditionally the sole preserve of artists – to everyone else so that they can “take responsibility for themselves.” [6] This implies that sign art is not only the most concrete kind of representation of the separate reality of human life, but also its most democratic. While the mirror paintings are democratic in the sense that everyone and everything is included in them in principle, the physical presence of a viewer who looks at the work and sees themselves in it is not strictly necessary – the absence of a spectator is still included in the work, even if this can’t be witnessed, and is marked by the spectral, unseen hand of the artist .

Michelangelo Pistoletto, “Terzo Paradiso ‘1+1=3’,” 2003–23

Pistoletto considers the mirror paintings to “constitute the foundation” [7] of his work. With a slight modification in how we understand how they work, they can also give us some of the conceptual basis for making sense of his other works, including sculptures like Third Paradise 1+1=3 (2003–23), The Reintegrated Apple (2007–19), or a more straightforward photographic self-portrait like QR-Code Possession: Self-Portrait (2019–23). These works present us with another version of virtual multiplicity. This is not just about how there are as many different views of the object as there are spaces to position it or people to view, nor how the object we see in front of us is only provisional, always subject to change. It is, then, not just a many/one relation in which the differences that make up manyness are subordinated under a higher concept of oneness, but “an organisation belonging to the many as such, which has no need whatsoever of unity in order to form a system.” [8]

The viewer sees this at the very beginning of “Many of One,” with QR-Code Possession: Self-Portrait. This huge photograph captures Pistoletto from the hips up, striped shirt half-off, with his forehead, bare chest, and left arm temporarily tattooed with twelve QR codes that, in their centers, contain his own personally modified infinity symbol – in which the line crosses itself twice like a moebius strip to produce one bigger oval framed by two smaller ones. This, allegedly, opens the door to what Pistoletto calls the “Third Paradise,” since the central circle acts as “the place where it is up to us to join them, so that they can impregnate the womb of a new society.” [9]

QR-Code Possession is evidence of Pistoletto’s optimism about what art can do, even in the face of dramatic technological change. At the same time, it subverts the troubling sight of a fragile human body whose skin has been imprinted, possibly by some machine, with a kind of serial number. Pistoletto’s infinity symbol is, however, not just an empty image of the imaginary realm of the Third Paradise – the symbol and the place or state of mind or being it represents come, somewhat inevitably, with a set of theories. They’re symbolized in different forms in The Reintegrated Apple and Third Paradise 1+1=3, while his written description of the Third Paradise offers a strange spiritual anthropology charting the history of the development of human consciousness from the childlike Edenic stage of the First Paradise to the Second, an age of knowledge in which humanity creates the world in its own image.

The Third Paradise, however, is “the passage to a new level of planetary civilisation, essential to ensure the survival of the human race,” [10] an age in which each human being takes responsibility for the relation between the artificial human world and nature at a global level. Pistoletto says that this is analogous to what he calls “Hominitheism,” a negotiation between pantheism and atheism in which, he thinks, monotheism can be replaced with a kind of religion in which each of us is divine. This is represented by The Reintegrated Apple, an oversized sculpture of the fruit with what could be a bite mark in its side surrounded by metal “stitches.”

In 2015–16, Pistoletto installed eight-meter-high steel versions of The Reintegrated Apple outside the Piazza del Duomo and Stazione Centrale in Milan. In “Many of One,” however, it appears in a far smaller form, made of what looks like furry felt or wool as part of the exhibition’s “Symbology” and “Ecology” Uffizi (offices, or rooms). This is partly an ecological Biblical allegory, but it also suggests, in Pistoletto’s inimitable style, the transition from the Second to the Third Paradise – from Adam and Eve biting the fruit of the tree of knowledge, creating the world in the image of humanity, to a stage of human autonomy in which humanity collectively neither denies nor asserts that God exists, but takes responsibility for both possibilities on the basis of each individual’s own capacity to think and feel freely.

The stitching on The Reintegrated Apple doesn’t look quite the same as Pistoletto’s modified infinity symbol, but forms part of the Third Paradise – Formula of Creation family of works dating back to at least 2003. In the context of “Many of One,” the sign reappears not only in QR-Code Possession but also in at least two works that refer to humanity’s emotional responses to and responsibility for nature and life on this planet. The Third Paradise ISS, for example, is a photograph of the artist’s hand holding up a ribbon of the same shape in front of the circular window from a space station overlooking planet Earth, a reminder of the sheer wonder of that sight, which cannot help but make us feel a certain amount of awed gratitude. Meanwhile, Third Paradise: Nourishment, is a wooden cuboid box full of soil, with the symbol made out of seed or gravel with shoots of bright green grass emerging from it, another symbol of hope for the fate of a damaged planet and all creatures who live on it.

It’s too easy to read Pistoletto’s extravagant claims as sublime esoteric nonsense. There’s some truth to that, but it’s hardly beyond redemption. A charitable reading treats Michelangelo Pistoletto as a kind of mystical science freak in a way that just about predates the new age bullshit industrial complex that developed in the 1970s. Far from being a creepy Californian cult leader, Pistoletto is a true eccentric. Reading him in the light of someone like Deleuze then allows us to mitigate some of his work’s sheer weirdness, making it explicable in terms of higher mathematics or quantum mechanics. Pistoletto’s inflated claims for his own work, or art in general, aren’t going to solve any of humanity’s current or future problems, but it’s strange fun.

“Michelangelo Pistoletto: Molti di uno,” Castello di Rivoli, Turin, November 2, 2023–February 25, 2024.

Max L. Feldman is a writer based in London.

Image credit: 1. Photo Alessandro Lacirasella, 2. Photo Damiano Andreotti, 3. courtesy Fondazione Pistoletto; all images Courtesy Cittadellarte and Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea

Notes

| [1] | Germano Celant, Art Povera (New York: Praeger, 1969), 227–28. |

| [2] | Following Bergson’s argument in Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness [1889], trans. F. L. Pogson (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1910), 75–91, Deleuze presents several different explanations of this in Bergsonism [1966], trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (New York: Zone Books, 1988), 37–50; Difference and Repetition [1968], trans. Paul Patton (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), 240–54; and his 1969 seminar on “Multiplicities” at the University of Paris, Vincennes-Saint-Denis, trans. Timothy S. Murphy, available at WebDeleuze and Purdue University’s archive of translations: www.deleuze.cla.purdue.edu. |

| [3] | Michelangelo Pistoletto, “Mirror Paintings.” |

| [4] | Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image [1985], trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (London: Continuum, 2005), 129. |

| [5] | Michelangelo Pistoletto, “Hominitheism and Demopraxy,” 2012-2016. |

| [6] | Michelangelo Pistoletto, “Art Sign.” |

| [7] | Pistoletto, “Mirror Paintings.” |

| [8] | Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, 240. |

| [9] | Pistoletto, “Hominitheism and Demopraxy.” |

| [10] | Michelangelo Pistoletto, “The Third Paradise,” 2003. |