PLURIVERSALITY Sarah Messerschmidt on Shuvinai Ashoona at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

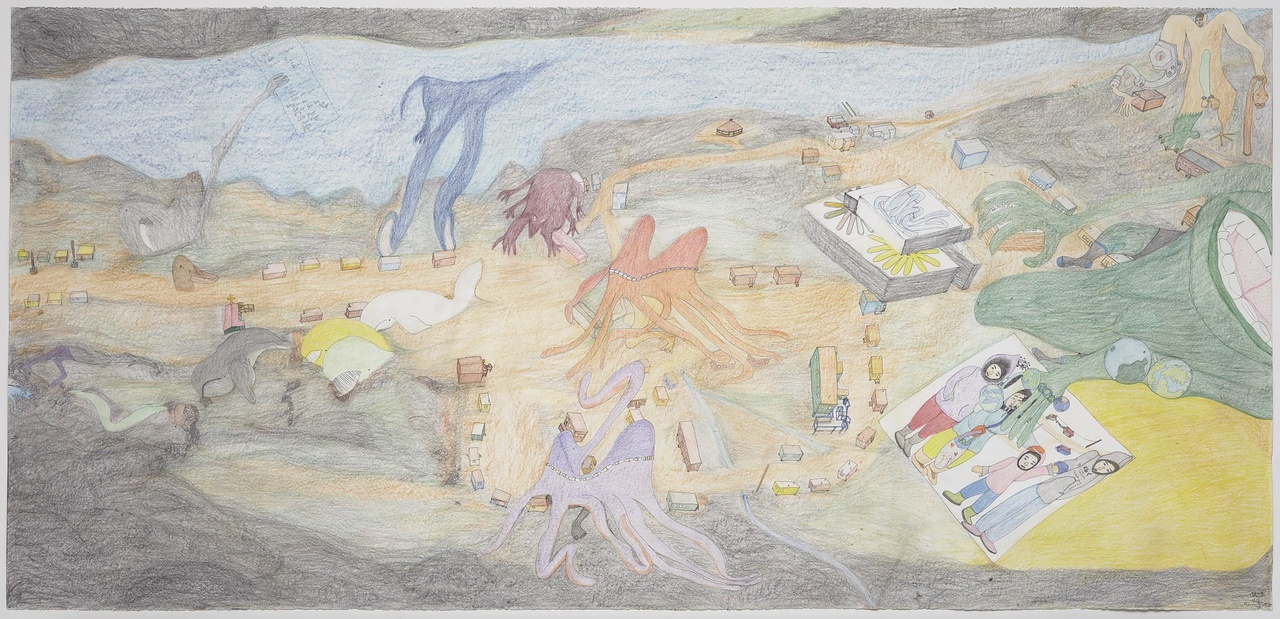

Shuvinai Ashoona, “Curiosity,” 2020

“I’m such a little person beside such a big universe,” [1] muses Shuvinai Ashoona. She is a soft-spoken woman, meandering and inventive in thought; contemplating aspects of the universe occupies a central place in her practice as a graphic artist. Ashoona is sensitive to parallel cosmologies, often capturing and intermingling multiple planes of reality in a single image to produce vividly illustrated montages. The exhibition “Shuvinai Ashoona: Beyond the Visible” at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) is a collection of 25 such idiosyncratic works of colored pencil and ink on paper that demonstrates the enigmatic visions she has of the world – or worlds – she inhabits.

For more than 20 years Ashoona has been drawing the landscape around her home in Kinngait, Nunavut, a small hamlet that sits on the northern tip of Dorset Island, nestled just south of Qikiqtaaluk (Baffin Island) in the Hudson Strait. The region has a tundra climate, with long, dark, frigid winters and extraordinarily cool, short summers. It is also home to Kinngait Studios, formerly the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, which since the late 1950s has supported numerous Inuit artists to produce and sell artwork, generally geared to markets in regions further south. Like her cousin Annie Pootoogook, another notable Kinngait illustrator, Ashoona depicts contemporary life as an Inuk person in the Canadian Arctic. In particular she renders the dual impact of colonial and environmental changes in Nunavut, and the resulting transformations in lifestyle as communities of Inuit shift from living on the land to living in settled communities, a process that unfolded steadily over much of the last century. Yet while Pootoogook was an avid chronicler of domestic life, Ashoona’s drawings portray a nebulous merging of the fantastic with the everyday, of dream-like imaginings with the realities of contemporary life lived in the Circumpolar North.

The development of Ashoona’s artistic style over time appears to echo the dramatic changes of her environment, and this is evidenced by the selection of works on show, which range from monochromatic illustrations that date from her early career – these typically depict features of traditional Inuit lifestyle, like the animal skin tupiq [2] in Tent Interior (2005–06) – to the more recognizably whimsical works of her current practice. Yet the exhibition’s curation avoids imposing a strict chronology on Ashoona’s work, rather allowing the drawings to fill the space with memories and stories. Curator Wanda Nanibush’s influence is visible here: an Anishinaabe educator and curator of Indigenous art at the AGO, Nanibush has substantially expanded the representation of contemporary Indigenous artists at the museum during her tenure, and has emphasized the import of unlearning the colonial proclivity to classify and arrange.

“Shuvinai Ashoona: Beyond the Visible,” Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 2021 installation view

There is no clear hierarchy of reality in Ashoona’s drawings, but a fusion of many possible realms: the fantastic, the mundane, the traditional, the historic, the modern. All are collapsed into the visual narratives presented in this exhibition. There are folkloric references – the Inuit sea goddess Sedna, a feminine spirit whose animal children provide sustenance for the Inuit, makes a notable appearance in Wild Pony with Sedna (2020), figured here tenderly stroking the mane of a tired horse; there are seemingly more personal memories, like the whale hunt pictured in Catching a Beluga (2019); and there are references drawn from contemporary popular culture – Ashoona loves horror movies and comic books especially, and monstrous creatures, such as the bicephalous gorgon of Dream Curiosity (2018), frequently feature in her pictorial interpretations of the Arctic landscape. A lover of music, Ashoona is also an iPod enthusiast, and these small gadgets – pieces of Western modernism that have entered into the fabric of life in the North – are sketched into Animals Listening to Music (2020), playfully attached to the ears of arctic fauna, who are clutched like babies in the laps of seated people.

A large, elongated drawing, the Summertime (2019) panel takes a surreally aerial perspective above three figures holding aloft a round earth, the cosmic angle of the image somewhat reminiscent of Salvador Dalí’s 1951 Christ of Saint John of the Cross, with its vertiginous view from the crown of Christ’s head opening out to infinite space. In Summertime, the strain of supporting such a massive weight is made clear by the braced legs that bend to either side of the globe, while alligators and summer moths inexplicably surround the figures in their extraterrestrial effort. The image is polarized by opposing light and dark halves that suggest an allegorical scene, but an allegory for what remains unclear. Nevertheless, Ashoona has been known to incorporate Christian iconography into her work, and certainly the godlike perspective, intimate yet omniscient, is not out of place in this composition. Similarly, at the entrance to the exhibition is a photograph of the artist stretched out flat on her stomach, pencil pressed to paper, evoking this same imminent and overhead position.

The world as a motif appears throughout Ashoona’s drawings, incorporated into her illustrations as round globes of varying size and color. Sometimes they are the dominant object, implying something all-encompassing and singular. In other cases they are scaled down and multiple, like playthings of the creatures who inhabit Ashoona’s drawn terrain – clusters of Blue Marbles dispersed across time and space. Shovelling Worlds (2013), for instance, depicts an Inuk man scooping many such globes, possibly to or from the wooden crate behind him. The geography of each globe is unique, and unmatched to the cartography of any Western world map. In an artist talk Ashoona explains that for her, the depiction of many worlds is often a representation of people who have passed away, suggesting that within one person exists an entire world unto themselves. [3] A landscape of flat stones provides a textured background to the scene, evoking a unity between the worldly and otherworldly spaces she pictures, and a further connection is forged between each tiny earth. Astoundingly, Ashoona draws intuitively, making no preparatory studies before beginning a work. Instead, her sketching of elaborate and layered stories is automatic and instinctive. The intricacy of each image, laid out on an unmapped field of white paper, is a delightfully fortuitous outcome for someone so interested in charting territory.

“Shuvinai Ashoona: Beyond the Visible,” Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 2021 installation view

Compositions (Titanic Plus Nascopie & Noah’s Ark) (2008) folds three famed shipwrecks into one, with references to Hollywood, the Bible and local Kinngait history – the Nascopie was a supply ship that, until its sinking in 1947, was the primary carrier of imported goods to the North. An enormous squid moves through the water ahead of the mythical hybrid vessel, pursuing four Inuit fishing boats while a white-winged Pegasus looks on. There is a granular effect of colored pencil on paper, which lends texture to an otherwise flat surface. This same river is documented on the single three-dimensional object on display, Composition (Cube) (2009), on which Ashoona has drawn the mountains and roadways of her home. The sculptural quality of this piece is a playful expansion of an ostensibly two dimensional genre into physical space. Ashoona lifts the geography of Kinngait into a multidirectional unit that both mythologizes the landscape – she claims the width of the river in her composition is inaccurate, a draft based on memory – and accounts for its environmental changes.

Ashoona’s world on paper is multiform: a constellation of memories, myths, and imaginings that make up her consciousness. Wild and playful, the drawings she produces express entanglements of her own interior and exterior worlds in a curious mixing of the experienced and the illusory. She moves nimbly between and across spaces of reality, quietly challenging the perceived universality of Western systems of knowledge and integrating a multiversal and Indigenous worldview that permits the coexistence of many planes of experience. However, though Ashoona’s work is widely celebrated – a selection of her works on paper was included in the 2020 Berlin Biennale, and she has been exhibited internationally several other times – her place in the dominant paradigm of the contemporary art world raises questions about whether the export of Inuit art positively affects the communities the cooperative system supports. Ashoona’s work certainly enjoys great institutional success, and she and Annie Pootoogook are often credited as having developed a distinctly contemporary Inuit style that is esteemed for its originality, yet the material conditions of many Inuit communities largely do not reflect such philanthropic interventions by arts organizations. Particularly in the remote North, Indigenous communities remain appallingly underserved and disadvantaged within the settler-colonial context of Canada. The efficacy of art patronage is perhaps limited to prominent individuals. Ultimately, this personal rendering of Ashoona’s Arctic home, though lively and magnetic, asks its audience to consider how colonial interference has altered Inuit life, and how these effects persist.

“Shuvinai Ashoona: Beyond the Visible,” the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, July 21–January 2, 2022.

Sarah Messerschmidt is a writer and researcher based in Berlin.

Image credit: 1 Courtesy the artist and Dorset Fine Arts; 2 & 3 Courtesy the artist, Photo: AGO

Notes

| [1] | Meeka Walsh quotes Shuvinai Ashoona in her profile of Ashoona in Vitamin D2: New Perspectives in Drawing, ed. Craig Garret (London: Phaidon, 2013), 32. The quote is also reprinted in: Nancy G. Campbell, “Shuvinai Ashoona: Life and Work; Biography,” Art Canada Institute, 2017, https://www.aci-iac.ca/art-books/shuvinai-ashoona/biography/. |

| [2] | Animal skin tents, or tupiit (pl.), are traditionally used by Inuit for shelter in seasonal camps. |

| [3] | “Art in the Spotlight: Shuvinai Ashoona,” Art Gallery of Ontario, AGO Talks, June 24, 2021, https://ago.ca/events/art-spotlight-shuvinai-ashoona. |