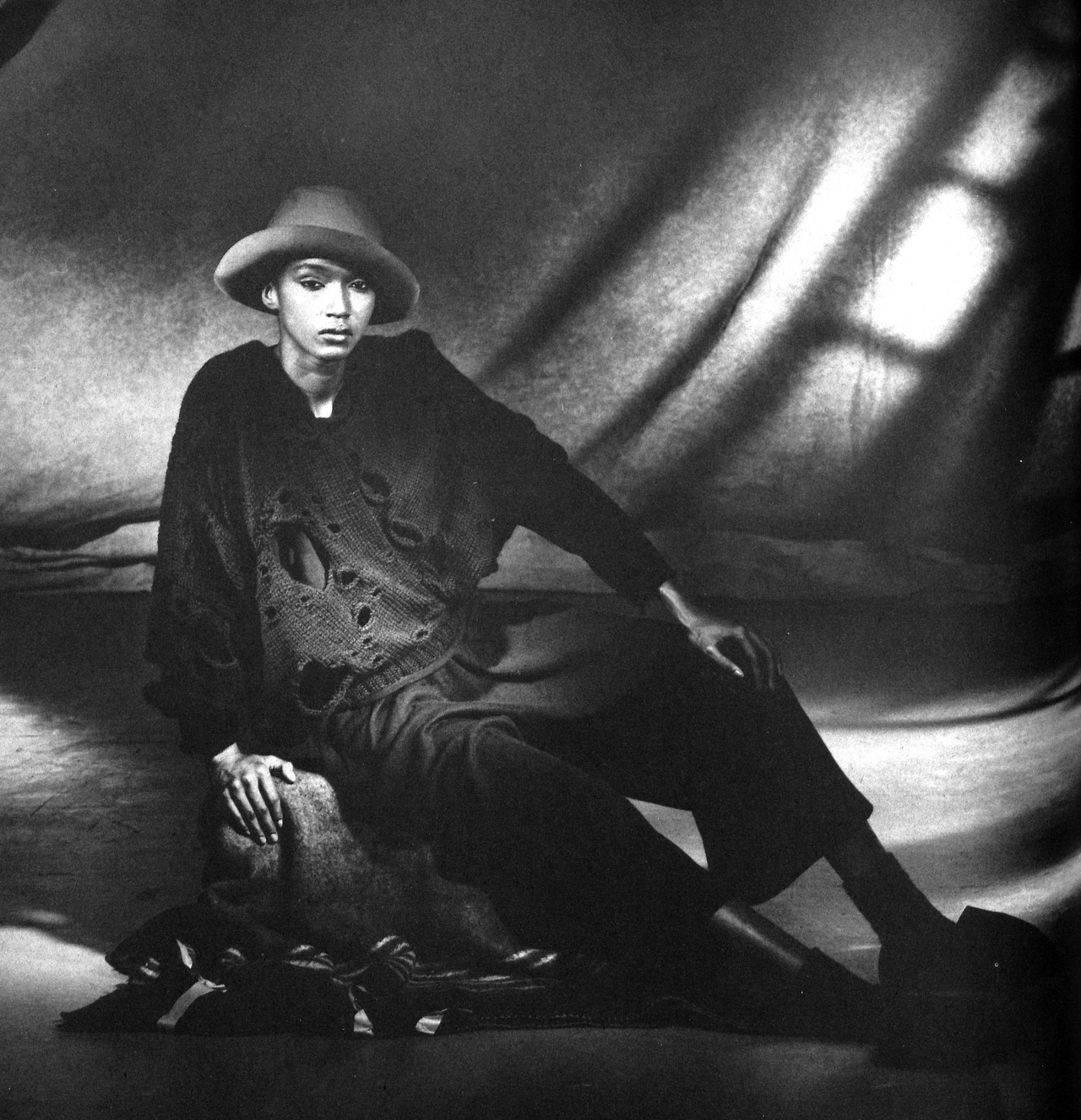

CRYSTAL MESH Existential imagery in current fashion

Backstage at Craig Green, AW 2016, Foto: Jason Lloyd-Evans

Backstage at Craig Green, AW 2016, Foto: Jason Lloyd-Evans

In the current rejection of all that is crisp, bright, and (perhaps falsely) wholesome – evidenced by, for example, the deconstructed denim of Faustine Steinmetz or the club wear of Nazir Mazhar – literary scholar and fashion journalist Ingeborg Harms discerns a revival of characteristic aspects of 1980s fashion, finding particular resonance in the strategies of such classic avant Japanese designers as Yohji Yamamoto and Comme des Garçons, efforts that can be traced to Junichiro Tanizaki’s famous “In Praise of Shadows.” This text’s current vogue, Harms argues, appears to be driven by a skeptical view of progress – one that manifests itself in, e.g., a taste for (lovingly?) restored clothes.

Likewise, references to 1990s functional apparel are legion: But by no means are designers now equipping an invulnerable ’90s “hardbody.” Rather, they stage a more precarious figure – even, perhaps, one ready to leave everything behind.

Fashion today is as bafflingly diverse as the music scene was in the 1990s. It copies, morphs, grafts, samples, remixes, and scratches ad infinitum. Yet despite this polyphony of styles playing out not just on parallel runways but often even within a single show, we can make out salient trends that offer indications as to the current zeitgeist. Amid a general climate of mistrust – of accelerating fashion cycles, of the ever-faster turnover of creative directors, and ultimately of what this means for quality and relevance – the dominant trend is a growing yearning for simplicity and moral seriousness. In fashion, this disposition translates into a renaissance of the Japanese aesthetic that emerged in the 1980s, namely via Yohji Yamamoto and Comme des Garçons, to challenge the maximalism reigning at the time. The Japanese designers’ understatement demonstrated that asymmetrical and recognizably unfinished clothes were the true couture in a world ruled by the industrial reproduction of prototypes. In a resurgence of this spirit, Junichiro Tanizaki’s manifesto “In Praise of Shadows” has once again become a bible for Western critics of consumerism.

Needless to say, it would be absurd to apply the values Tanizaki extols to the twenty-first-century Western world. His essay, first published in 1933, paints the panorama of a Japan of craftsmen, geishas, and feudal overlords. It glorifies a waning ethic of thrift, self-command, asceticism, and humility; of patience, respect for one’s elders, awe of nature, and the unquestioned acceptance of one’s own place in the order of things. The corresponding aesthetic does not award pride of place to the human being and his or her prowess. Rather, shine – of lacquered boxes or blackened geisha’s teeth – is kept to a minimum, and its adherents are ordered to endure all sorts of discomforts; and, unlike the Western Enlightenment, it has no intention of doing away with darkness.

Tanizaki himself already drew a contrast between the Japan of old he praised and the clinical brightness pervading the modern world of American consumerism. Technological progress and industrialism had created a counter-reality – the reality that, to this day, defines us – in which humans were largely relieved of the need for arduous manual labor and in which any trace of the human hand in fact came under suspicion of being unclean and contagious. People were free to purchase the product and contaminate it with their mortality, but at the expense of its immaculate purity: it was soiled the moment the transaction was completed, reducing the commodity’s value to a fraction of its price. In the aesthetic of the shadow, things accrued worth and dignity by use; the Western consumer product, by contrast, forfeited its fetishistic quality by merely coming into contact with the domain of actual application.

As the resource consumption required not only for the inexhaustible parade of products but also for their manufacturing, packaging, and dissemination has come to seem rather demoniacal, the reputation of traditional economies, their techniques and leading exponents, has risen. Recycled patchwork denim by Vetements and 69 is newly popular, as are the creations flaunting the flaws of the handmade that Faustine Steinmetz weaves on old looms and other, more symbolic affirmations of sustainability and espousals of patina: artfully applied moth holes, tears, rip-outs, and miscuts by Kapital, the Japanese father-and-son label that made products returned by customers because of defects the core of its business model – grotesquely disfiguring apparel manufactured with tender care and sold as the relic look.

And yet these new puritans have little in common with the American original. The people who crossed the Atlantic aboard the Mayflower and went on to found the United States made sure their clothes were neat, discreetly darned, and perfectly ironed and starched. Today’s ascetics, by contrast, purposely avoid such respectability. Their wear is demonstratively torn in every way, signaling existential drama with a whiff of self-mortification and martyrdom. The wounds suffered by the clothes stand for the vulnerability of the body. Gone is the impregnable hardbody of the 1990s, as a classical model has made a comeback: the body as the image of the soul.

Only this body lacks both the effortless poise of a Schillerian playful existence and the Puritan’s equanimity and unshakeable religious conviction. Instead of collective ethics we are witnessing the spectacle of a morality splintered by endless minute distinctions. It is rare today for two people to agree on what one can say, eat, buy, support in good conscience. Fashion reflects this dissension. It dreams of a world in which the clear structures, straightforward values, and august ideas of honor found in Tanizaki-style feudalism still hold, but its true hero is a romantic maverick clad in a fantasy uniform. His mental constitution is not too different from the ideas that spur teenagers from Western big cities to join the jihad. Whereas the extremist anticipating a martyred death banks on guaranteed admission to paradise, the Silicon Valley engineer of Dave Eggers’s novel “The Circle,” already living in paradise, hardens himself as though preparing for Holy War.

So it turns out the wave of political correctness that swept the world of fashion after the spectacular Clochard collection John Galliano designed for Dior in 2002 was never more than skin deep. Fashion is magically drawn to current political events and their protagonists: the refugee, whose existence is reduced to the sole objective of survival, and the jihadist, who rejects the lifestyle of the West and risks his life trying to bring it to its knees. Opulent layering and the “used” look are also fashionable allusions to homelessness, while martial design elements tend to aim at a conjunction of fundamentalist attitude and personal sensitivity. The current Raf Simons campaign is symptomatic in this regard: it combines the cozy warmth of a Norwegian-style sleeveless sweater with the provocation of hoods covering the face, bringing to mind both terrorists and hostages alike.

In women’s fashion, too, the influence of Islamic dress codes may be discernible in the prevalence of extra-low hemlines and often positively grotesque efforts to keep the shoulders covered. Yet this new love of veiling has more than one source. It signals that, amid an atmosphere of surveillance, of emergency laws and heightened police presence in public spaces, transparency, even in the merely sartorial sense, has started to feel creepy. Here, the “used” look aims for anonymity to deflect curious gazes, or to mask specific body shapes, or even to serve as intimidating role-playing-game wear. People become their own real-life avatars and take Game of Thrones to the street, arming themselves with chest guards and exoskeletons, Samurai gear, heraldic appliqués, and 3-D ornaments.

This new penchant for the bluff, the ruse, for simulation and dissimulation can be observed in men’s as well as women’s fashion. The lone warrior has emerged as icon of the new gender paradigm, the counterpart of the sexual camouflage look in which gender codes are mixed ad libitum. Such styles seem to reach for Western hero figures that are far from both the jihadist and the capitalist cynic. Seeking inspiration, designers are torn between the protective wear of modern risk management – of disaster crews, paramedics, and toxic-waste removal specialists – and historic references. Umit Benan conjures Fidel Castro’s rebels, Gosha Rubchinskiy brings back the synthetic fibers and color blocking of Soviet athletics, Hood By Air quotes the gladiatorial archetypes of graphic novels, while Craig Green and Nasir Mazhar sing highly sexualized martial-arts arias. Even machine-age workwear is fodder for the heroism fad: the deconstruction of the digital spring leads straight into a romantic vision of the working class. Louis Vuitton has mechanics’ wear, meanwhile references to firefighters and construction workers are everywhere. In the spirit of the Western fitness cult, they complement Junichiro Tanizaki’s praise of manual craftsmanship with the adulation of brawn.

So while the end of consumerism is hardly nigh, a new skepticism of progress is distinctly palpable. It does not take a wise Japanese teacher to recognize that a forty-year-old Mercedes-Benz, a twenty-year-old Prada coat, and, for some people, even a Nokia cell phone are better quality – more reliable, practical, discreet, and emotionally satisfying – than their latter-day equivalents. By limning the aesthetic effect of a lacquered box in the twilight of a Japanese interior, Tanizaki not only sensitizes us to the value of objects made by hand out of natural materials; he also pillories the cultural colonialism that transplants usages, lifestyles, and objects from one country to another, watering down any generic product until it is thoroughly featureless. Still, to the extent that the fashion world gestures toward regionalism – and the impulse is certainly there – the communities in question are usually media tribes and the alliances virtual. Even when young fashion brands and local studios build loyal clienteles, that’s hardly a return to aesthetic regionalism of the sort Tanizaki had in mind.

In some ways, this is for the better: just as traditional aesthetics are rooted in the landscapes, climates, mentalities, and rituals of specific places, aesthetic innovation in the global village is rooted in air. Mindsets and sensitivities travel around the globe under people’s skins, accumulating creative input until a new pop culture takes shape. Beneath the mask of romantic regression, fashion right now appears to be getting over its energy-sapping and escapist fixation on anything vintage. No longer stymied by its obsession with various fashion periods of the past, it is tentatively beginning to outline its own myths and devise an expression for novel complexities. It cultivates a leeway in which ethical propositions, questions of dignity, and individual life choices can be articulated. As its influence as a trend engine wanes, its political significance is growing precisely because, in its fractured state, it reflects the fragmentary nature of today’s constructions of self. As the celebrity designer system and the dictatorship of the brands are collapsing, fashion’s metamorphosis adumbrates ways out of the capitalist stasis. Responsibility is the new catchword for sustainable luxury (just as the demonstrative forms of responsibility are a luxury), but it is not just about the manufacture of fashion: it also describes the consumers who are looking for clothes that will mature along with them. That is the desire fashion must cater to if it is to survive – its secret has always been momentary rebirth.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson