BODY OF EVIDENCE, GESTURES OF DYSFUNCTION Giovanna Zapperi on Technology as Practice in the Work of Natascha Sadr Haghighian

Natascha Sadr Haghighian, „d(13)pfad / d(13)trail“, 2012

Natascha Sadr Haghighian, „d(13)pfad / d(13)trail“, 2012

When contemporary art is overloaded with putative gestures to social consciousness and calls to action via the language of participation, how can current practitioners summon a less self-congratulatory mode of activism without losing the powerful devices of the language of artistic form? The difficulty seems to lie in artists’ ability to investigate the crossover of seemingly unrelated fields and disciplines, whether through archival research or audience-generated displays.

To confront this problem, art historian Giovanna Zapperi looks to the work of Natascha Sadr Haghighian and discovers a “productive entwinement between political activism and a critical understanding of technology.” Zapperi identifies this as an effective direction for politically-minded artists. In doing so, she outlines a new theory of praxis in which “parody can perform the work of critique.”

The contemporary art field is a space in which it is possible to experiment with ways of doing politics. The question remains, however, as to what impact these self-declared political practices – both in and out of the art world – are capable of making. While activism is often present at art events (which are purportedly eager to support critical thinking and politicized perspectives), the material and discursive conditions of art’s dissemination (i.e., powerful institutional apparatuses as filter) tend to neutralize political agency. Large-scale art exhibitions – such as, for example, Documenta 14 – are paradigmatic of precisely this dynamic wherein critical thinking is prized but also limited or self-contained. [1] Because activism tends to have a bad name in general, activist participation in art-world circuits can offer some cultural validation. However, this comes with a loss of some degree of political efficacy for the sake of visibility. But there is also another, less obvious dimension to this ambivalent position: its effect on the ontology and status of what is considered “contemporary art” at large, seeing as it forces one to ponder the distinctions between “art,” “evidence,” and “research,” or “subjectivity” and “objectivity.”

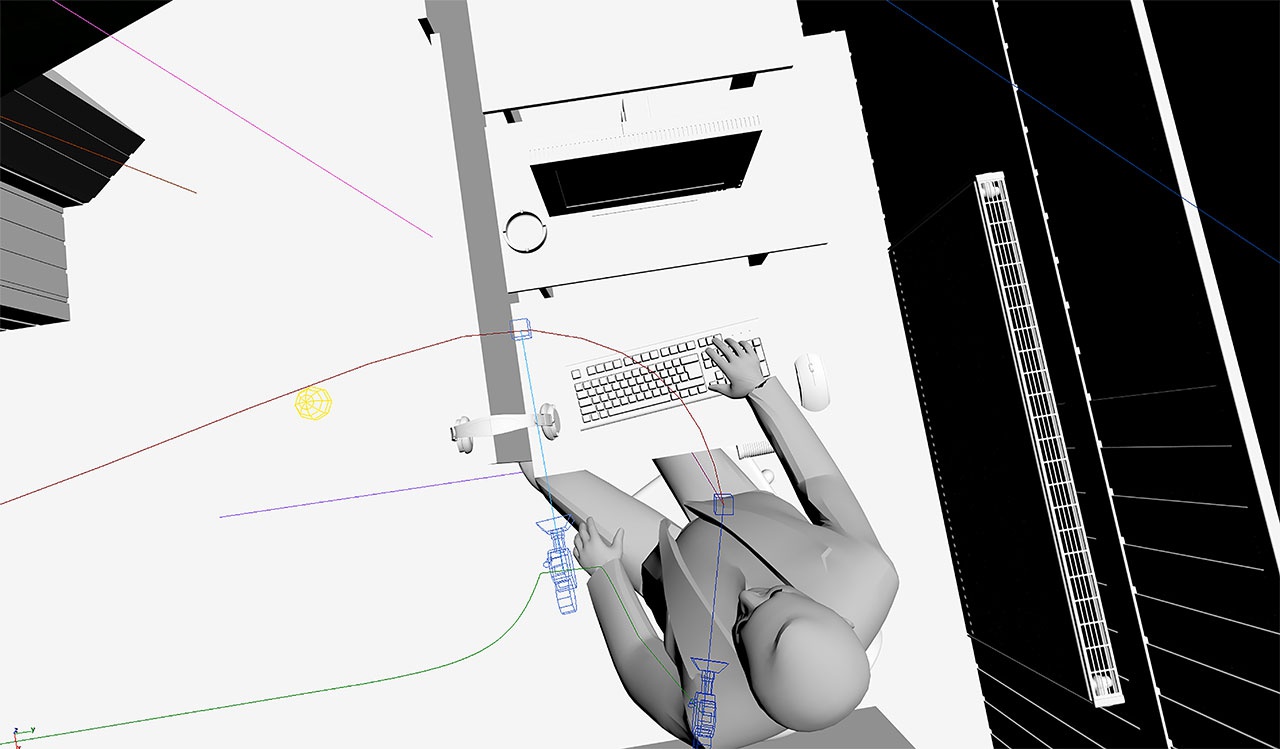

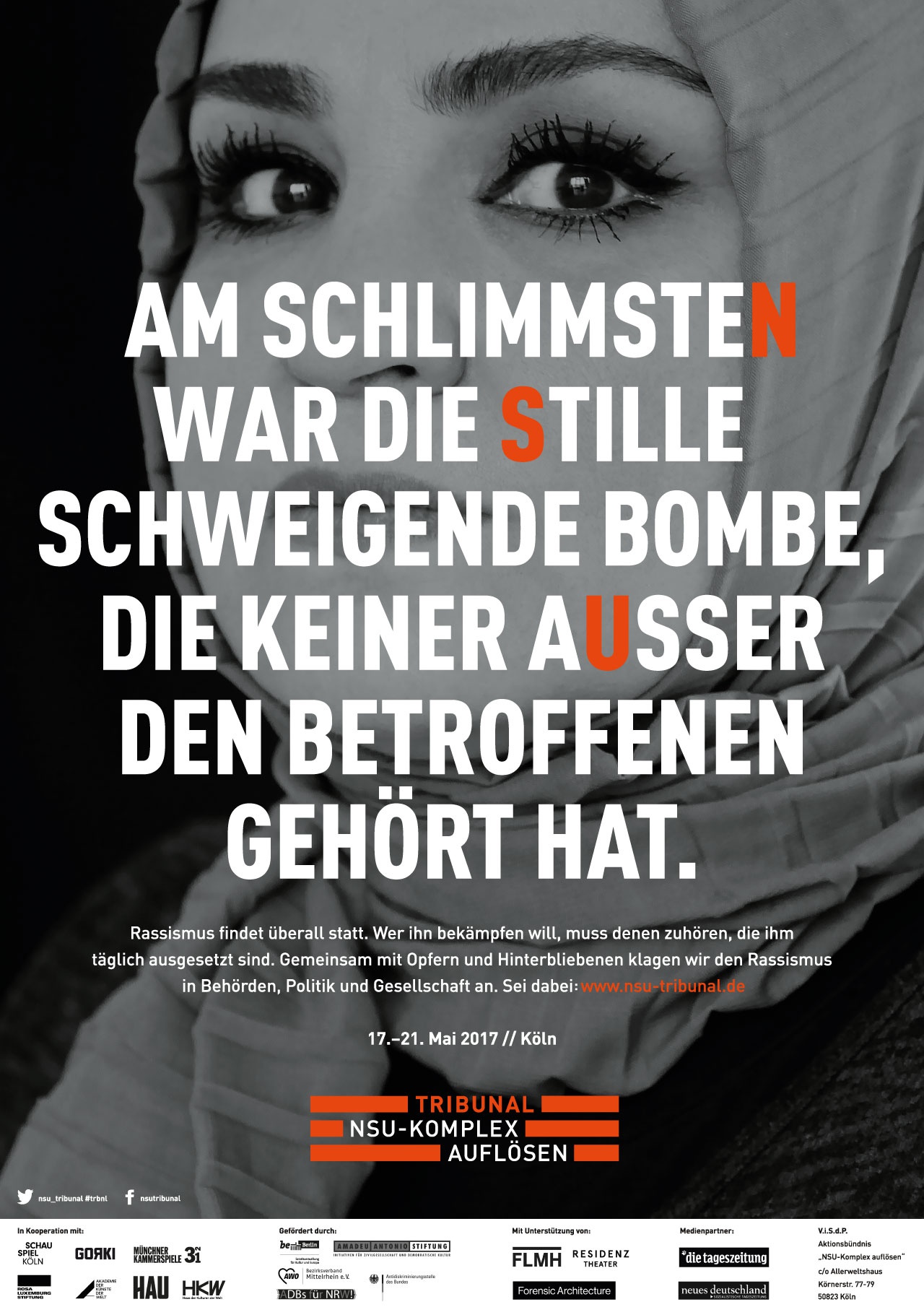

The collaboration between the Goldsmiths-based independent research center Forensic Architecture and the Society of Friends of Halit – with reference to Halit Yozgat, killed in Kassel on April 6, 2006 by the neo-Nazi organization known as the NSU (National Socialist Underground) – is a case in point. The group’s multipart presentation, which dealt with the articulation of neo-Nazi terror and institutional racism in Germany, was centered around a video produced by Forensic Architecture titled “77SQM_9:26MIN” (2017), reconstructing the involvement of an undercover agent of the German intelligence service, Andreas Temme, who, though present at the time of the murder, was cleared in court. [2] The video recreates, both virtually (via 3D animation) and physically (via material reconstruction of the space), the scene of the crime and develops three possible scenarios, which together show that Temme’s alleged involvement in the killing is in fact very likely.

Forensic Architecture, Full-scale mock up of internet cafe, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), Berlin, 2017.

Forensic Architecture, Full-scale mock up of internet cafe, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), Berlin, 2017.

The video takes the form of an autonomous investigation and integrates technological and juridical expertise to effectively make a call for justice. Interestingly, the group’s use of technology – despite the fact that this video was produced as part of an ongoing effort to reopen Temme’s case and thus followed a specialized protocol of handling evidence that the space of art is unable to fully safeguard – had a special currency in an art context. The “technology” (filmic animation, interactive cartographies, and 3D modeling) taken up by Forensic Architecture and deployed by them in a positivistic way, functioned as a tool to objectively test Temme’s involvement. Although the inquiry ultimately failed in reopening the case, it nevertheless evidenced the political nature of the trial and succeeded in unveiling the connections between the state apparatuses and Germany’s systemic racism. [3] For any who might be concerned about art’s current fascination with right-wing imagery and new forms of technological fetishism, Forensic Architecture’s activity and alternate engagement with technology should be very welcome. [4] Thus despite the collective’s ambivalent positioning within the art world (neither born of nor identified with it, and yet still participating in its structures), their work in an art context very productively stirs us to question technology’s intersection with artistic production and whether objectivity as a formal grammar (instantiated by technological tools) can indeed be understood as an artistic form in itself.

Forensic Architecture, Computer simulation of motion tracking and vision simulation of Andreas Temme, 2017

Forensic Architecture, Computer simulation of motion tracking and vision simulation of Andreas Temme, 2017

Natascha Sadr Haghighian is an activist and artist who likewise occupies this ambivalent half-in, half-out art-world position; she was involved in the Society of Friends of Halit and is also one of the individuals involved in the collective initiative of “Unraveling the NSU Complex,” which commissioned Forensic Architecture’s video. Her involvement in the project followed naturally from the productive entwinement between political activism and a critical understanding of technology (i.e., maintaining a certain disbelief in it) that also characterizes her practice.

In what follows, I will look at some of Sadr Haghighian’s recent works – specifically pieces that explore the current militarization of everyday life – to address the complex entwinement of art, politics, and technology. Generally speaking, technology is an omnipresent theme in her practice; it’s an integral part of its content and materiality, as well as of the viewer’s experience of it. The works addressed here are ones that take the form of sculptural environments wherein everyday objects are activated by the viewer, sometimes suggesting the kind of interactivity typical of communication technologies. They are works that convey a fundamental distrust in technology’s ability to provide a better life. And yet her aesthetic is devoid of the kind of apocalyptic or technophobic imagery one could expect from such circumspection. On the contrary, Sadr Haghighian brings a critical dimension to her framing of tech, through an edge of irony that points to the decidedly gendered dimension of technological development, especially that which intersects the military complex.

Poster from the campaign “Resolving the NSU Complex!”, 2017

Poster from the campaign “Resolving the NSU Complex!”, 2017

Natascha Sadr Haghighian’s interest in military history and technologies started around 2012 in the framework of her project for Documenta 13: a work called “Trail,” which comprised the construction of a footpath in Kassel’s centuries-old Karlsaue park, which was partially reconstructed in the wake of World War II to absorb leftover rubble. With this piece, the artist brought attention to the military industry that has historically shaped the city of Kassel, which, nearly destroyed by Allied bombings, reestablished itself after postwar reconstruction as a node of the military industrial complex. In her subsequent explorations of the histories and technologies related to military development, Sadr Haghighian has become particularly interested in the osmosis between sections of society that are usually presented as separate, such as local law enforcement and federal defense efforts. In her work “Pssst Leopard 2A7+,” the relation between military imagery and the gendered body emerges through the specific material strategies adopted by the artist. First presented in 2013 at König gallery in Berlin (but comprising a continuously developing sound component), this installation takes the spatial footprint of a battle tank (the Leopard 2A7) created by the German defense company Krauss-Maffei Wegmann as an armored vehicle intended for deployment in urban environments. Press materials for the tank speak of it being used in “Peace Support Operations.” But its development around 2010, thus coinciding with the wave of revolutions that took place during the Arab Spring, suggest that “peace” in this formulation might better be replaced with “suppression of civilian dissent by military means.” [5] Sadr Haghighian’s recreation of the vehicle is pointedly, farcically demilitarized, however, seeing as it’s built of shipping palettes surfaced in white, green, and blue Legos (arranged in patches, like leopard spots or military camouflage), and features a circle of 60 headphone jacks outlining where the tank’s central turret would be.

Given that the body is a constant concern in Sadr Haghighian’s work, it is of particular note that in dealing with military technology and imageries she avoids any explicit representation of the human form, male or otherwise. Rather, she frames the viewer’s own bodily experience by, for instance, creating a contrast with the body language one might normally associate with such an object. This model tank invites visitors to sit or lie on the platform and listen to different soundscapes that refer to the particular uses and history of this tank as if to share the not-so-hidden secret of the Leopard 2A7’s actual use. [6] Rendering the tank’s form an interactive playground, Sadr Haghighian reduces the Leopard’s roar to a whisper by way of the viewers’ involvement. It is the listeners who climb aboard the model tank and who, in turn, consecrate the process of undermining the tank’s function that the artist has set in motion; it is the viewers who deweaponize the idea of this object and who, as diverse civilians, likewise degender the cultural associations between boyhood and “playing war.” In so doing, it is also the viewers who effectively mock the normative masculinity that traditionally comes with the representation of warfare. [7]

Natascha Sadr Haghighian, „Pssst Leopard 2A7+“, 2013

Natascha Sadr Haghighian, „Pssst Leopard 2A7+“, 2013

Associating sculpture with playground design also refers to conventional inscriptions of masculinity in modern art. “Pssst Leopard”’s flat, geometrical structure, with its grid-like array of colored panels, indeed alludes to Minimalist sculptures, such as Carl Andre’s typical idiom of flat, serial arrangement of squares, as in his “37 Pieces of Work” (1970), with its references to industrial labor and materials. Or perhaps even more poignantly, it recalls Pino Pascali’s 1965 “Le Armi” (Weapons) series, in which machines of violence were likewise converted into objects of play, specifically boys’ toys (although the referent warzone for this older series is Vietnam). [8] Both Minimalist sculpture and Arte Povera’s version of the readymade indicate a time of industrial production, when the model of factory work was in the process of being replaced by immaterial labor and the technological environments to which Sadr Haghighian’s work alludes. [9] If the reproduction of toylike bombs, cannons, and machine guns was consistent with the staging of Pascali’s hyperbolic masculinity – in which childhood memories are interpolated with the heroic image of the artist – Sadr Haghighian’s “Pssst Leopard 2A7+” unpacks both the cultural topos that reinforces the archetype of the hero-like (male) artist figure, as well as the canonical formal vocabulary of Minimalist sculpture. “Pssst Leopard” proposes a different kind of sculpture, a sculpture exposing the symbolic and gendered connection of these tropes: the wild animal, the weapon, and the (male) artist.

Tank Leopard 2 A7

Tank Leopard 2 A7

The idea of developing a tank specifically designed for urban operations marks another piece of overlap between the history of civil society and the military industry. This osmosis, however, is not carried out just in the field of weapons manufacturing, but encompasses various aspects of everyday life, especially those involving technological innovation. Another recent project by Natascha Sadr Haghighian focuses on the question of the gaze and technology, with reference to the ways in which research initiated within the weapons industry has found its way into civilian use. The application CatchEye, for example, stems from the kind of explorations in 3D mapping that are common to the military tech industry; in this case, image correction software that could be incorporated into the programming of communicational apps like, say, Skype or WhatsApp. What CatchEye does is detect users’ faces on screen and align their respective gazes to correct the phenomenon of parallax viewing (wherein lines of sight miss each other as each user looks at their screen rather than into the camera), creating the illusion that users are looking directly at each other and thus enhancing the sense of proximity and presence.

Sadr Haghighian’s 2017 installation “onco- mickey-catch” includes this CatchEye software. In the work, two computer monitors are implanted on an animal-like form, so that the screens seem to literally originate from the headless body. The shape of the sculpture suggests an updated version of the “Vacanti mouse,” a 1990s lab mouse famed for, thanks to science, growing the likeness of a human ear on its back. Further references contained in the title point to Disney’s Mickey and to the OncoMouseTM (a breed of lab mouse optimized for cancer research on account of its susceptibility to the disease). Meanwhile, the sculptural taxidermy that serves as the base of this work suggests the anatomy of a mouse. And indeed a collapse of boundaries between the organic and the mechanic is precisely what the work drives at, implicating living bodies in the dissolution between techno-science and the entertainment industry. [10]

In “onco- mickey-catch,” the conflation of software, body, screen, and the gaze produces the representation of a dissolution of difference between the organic body and the technological apparatus. The staging of this mouse trio (to which one could add a fourth – the computer mouse) proposes a slippage between these items associated with three distinctive cultural sectors (entertainment, biotechnology, and computer sciences), resulting in a sort of dystopian, dada-like assemblage. This construction of organic and inorganic components is indeed reminiscent of the Surrealist taste for absurd materialist encounters, such as, for example, Meret Oppenheim’s famous 1936 “Fur Cup,” wherein a piece of a mammal’s coat is affixed to the cold, flat porcelain surface of a common consumer good. As with the aforementioned works by Sadr Haghighian, “onco- mickey-catch” likewise invites the viewer to experience the work through some kind of physical interaction. The positions of the two screens in the work make it is possible to video chat with the person sitting opposite; the incorporation of the CatchEye software enables a pair of users to lock eyes via the screen. Given the close bodily proximity of the two users, the technology (originally designed to overcome distance) as employed here renders the mediated encounter a caricature or pointless convenience.

Natascha Sadr Haghighian, „onco-mickey-catch“, 2016

Natascha Sadr Haghighian, „onco-mickey-catch“, 2016

In fact, “the gaze correction software that makes it possible to make eye contact, does not allow you to look away,” as Sadr Haghighian has noted. [11] Beyond the mocking representation of this part-animal, part-dysfunctional machine, what is at stake is the pervasive application of biometric technologies of identification and surveillance in everyday life. In the cultural logic of the information age, the screen, per Jonathan Crary, is both the object of attention and the object that monitors, records, and references human behaviour. [12] The gaze of the screen reverses the gaze of the beholder, it “looks back” at the viewing subject, like a disembodied, mechanical eye. Referring to Donna Haraway, Sadr Haghighian also indicates the entanglement between such contemporary models of “absolute vision” and the genealogy of modern objectivity, based on the assumption of a non-marked (white, male) conquering subject of the gaze, to which Haraway opposes a feminist epistemology based on “partial perspective” and a different understanding of objectivity. [13] The techniques of vision are questioned in their “ways of seeing” and their entanglement with power such that doubt is cast on the possibility that such visualization technologies could ever truly capture the full complexity of human interactions.

This inquiry into the circuits of power, vision, and technology asks whether present-day techniques of vision can indeed be used to articulate or perhaps even enact tactics of counter-visuality in a given social struggle. Sadr Haghighian uses her work to question emerging technology as the very site in which power relations are produced and enacted. To go back to the example of Forensic Architecture and their “extra-disciplinary” [14] formal language, the kind of critical examination carried out in Sadr Haghighian’s works rejects the language of objectivity that is necessary in the context of a trial. Rather, the specific visual and material qualities of her work align with those encompassed by the cultural idiom in which art-historical references are connected to a number of contemporary social practices, thus clearly positioning her practice in the realm of art. Instead of providing professional (non-art) expertise, her productions suggest that parody can perform the work of critique. The point is not an exploration of the political uses of technology, but one that takes technology itself as its object, unpacking its entanglement in a variety of social practices. One could argue that here we have two fundamentally distinct ways of understanding the relation between objectivity and politics: in the first case, technology is perceived as a tool that can be used in order to objectively interpret the facts (and in this case call for justice); in the second, the elaboration of a specific idiom allows for a reconsideration of technological objectivity in its involvement with power.

Sadr Haghighian’s appraisal of the entwinement between power and technology is key to her avoidance of the type of mimicry that is currently so common in (mostly, although not exclusively, male) artists’ interest in the glossy surfaces of communication technologies. [15] Her works are indeed characterized by an anti-spectacular idiom, one which includes a specific emphasis on everyday gestures and bodily experience and that can be read in the framework of an ongoing feminist project of undermining the canonical inscriptions of greatness. This attitude opposes the aura of importance that typically comes with the representation of male activities across culture. Her distinctive humor is equally crucial in overcoming the oversimplified binarism of technophilia and technophobia, seeing as it emphasizes, instead, the subject’s (or user’s) agency over technology. Fascination is replaced by a more nuanced appraisal of the technological environment as structurally broken and dysfunctional, and yet deeply entwined in the definition of who we are. This is perhaps one of the reasons why her works leave so much space to the viewer: because the point is not to look at the technologically novel object itself – the flat screen as a contemporary fetish – but rather at how it informs the way we act and relate to each other. To engage with the technological object in such ways activates the viewer to override passive tendencies and attempt to interfere within the circuits of communication and control. Uses (and misuses) of technology in this work are thus explored via an array of small gestures of ordinary subversion. If communication technologies and power have always been intertwined, Sadr Haghighian creates interferences that engender acts of interruption with the aim of loosening control and exposing, via bodily person-to-person experience, the overload of meaning in which our lives are increasingly entangled.

Notes

| [1] | Some critics have pointed out the political relevance of certain works that most effectively addressed the state of democracy and social justice within Documenta’s geopolitical scope (which this year directly connected Germany with Greece). See for example T. J. Demos, “Learning from Documenta 14: Athens, Post-Democracy and Decolonization,” http://thirdtext.org/demos-documenta; see also Hili Perlson, “The Most Important Piece at Documenta 14 in Kassel Is Not an Artwork. It’s Evidence,” https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/documenta-14-kassel-forensic-nsu-trial-984701. |

| [2] | The investigation was jointly commissioned by an alliance between art institutions and activist groups: the People’s Tribunal, “Unravelling the NSU Complex,” Haus Der Kulturen Der Welt (HKW), Initiative 6 April, and Documenta 14. More detailed infos about the tribunal can be found here: http://www.nsu-tribunal.de. For the results of Forensic Architecture’s investigations, including the above-mentioned video, see http://www.forensic-architecture.org/case/77sqm_926min/. |

| [3] | The results of the investigation were submitted to the Bundestag’s and Hessen’s parliamentary inquiries, but were rejected by an internal CDU report. Interestingly, the CDU report refers to Forensic Architecture as an “artist group” in order to discredit it. See Forensic Architecture’s official response: http://www.forensic-architecture.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Response-to-CDU_2017.09.19.pdf. |

| [4] | I am referring here to the works discussed by Anselm Franke and Ana Teixeira Pinto in “Post-Political, Post-Critical, Post-Internet: Why Can’t Leftists Be More Like Fascists?,” http://www.onlineopen.org/post-political-post-critical-post-internet. |

| [5] | Note that this type of tank is currently operative in Qatar and other parts of the region. |

| [6] | Some of these soundscapes can be found online: http://possest.de/2013/12/31/pssst-leopard-2a7-2/. |

| [7] | The army has historically played a crucial role in defining the modern contours of masculinity, notably through the formation of physically powerful bodies, bodies that are armed, impenetrable, and invariably gendered as male. See George Mosse, The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity, Oxford 1998. |

| [8] | Pascali stated that works in this series were designed to look like weapons and sculptures at the same time. See Alex Potts, “Autonomy in Post-War Art: Quasi Heroic and Casual,” in: Oxford Art Journal , vol. 27, no. 1, 2004, p. 183. |

| [9] | Natascha Sadr Haghighian has developed this point in some of her texts, where she muses on possible uses of technology; see in particular “Disco Parallax,” http://www.e-flux.com/journal/61/60991/disco-parallax/. On the question of industrial and artistic labor in 1960s Italy and the US, see Jaleh Mansoor, Marshall Plan Modernism: Italian Postwar Abstraction and the Beginnings of Autonomia, Durham, NC 2016, pp. 140–51. |

| [10] | Onco MouseTM is a genetically modified “trademark” animal created in the 1990s for the purpose of cancer research, specifically breast cancer. As Donna Haraway affirmed: “OncoMouseTM is my sibling, and more properly s/he, male or female, is my sister. […] Her natural habitat, her scene of bodily/genetic evolution is the technoscientific laboratory and the regulatory institutions of a powerful nation-state.” D. Haraway, Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan©_Meets_OncomouseTM: Feminism and Technoscience, New York 1997, p. 79. |

| [11] | Natascha Sadr Haghighian, “Parallax,” in: Katrin Klingan et al. (eds), Textures of the Anthropocene, Cambridge, Mass. 2015, p. 136. |

| [12] | Jonathan Crary, Suspension of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture, Cambridge, Mass. 1999, p. 76. |

| [13] | Natascha Sadr Haghighian, “Parallax,” p. 138. See Donna Haraway’s notion of “situated knowledge” in: Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, London 1991, pp. 183–201. |

| [14] | With reference to Brian Holmes’s definition of the “extra-disciplinary.” See Brian Holmes, “L’Extradisciplinaire: critique des institutions artistiques,” in: Multitudes , no. 28, 2007, pp. 11–17. |

| [15] | Here, again, I am referring to the kind of work that can be loosely associated with the so-called “post-internet style,” which was notably prominent in the 2016 Berlin Biennale... [ |