Woman as Subject or Exemplary of Her Kind A Conversation between Maija Timonen and Rachel Cusk

Mary Kelly and Son, Recording Session, 1975

MAIJA TIMONEN: I wasn’t intending to lead with this question, but I noticed that we are sitting across the road from my analyst’s office, so I think I must. I was thinking about your trilogy (Outline, Transit, and Kudos), and the stories of the people the protagonist of these books, Faye, encounters. The way the books consist almost solely of these stories, with Faye as a largely silent recipient for them, evoked to me a fantasy of getting to have a monologue about one’s life, getting to talk about oneself without the attached social stigma, maybe also a kind of fantasy of being listened to. Which then led me to think of the psychoanalytic situation, where one talks about oneself to a relatively silent listener. Do you have an interest in psychoanalysis?

RACHEL CUSK: I’m very interested in psychoanalysis. I’m interested in a completely different angle of arriving at investigations of human nature, a whole different vocabulary than that of a novelist. This almost insolent power of investigating, describing, and understanding human behavior. I read a lot of psychoanalytic writing and find it very interesting because psychoanalysts – a Freud or a Donald Winnicott – can say things about humans that a novelist would never dare to say. And I suppose in terms of the trilogy specifically, it’s not so much that the style is taken from the psychoanalytic situation, but that I have come to the same conclusions by thinking about the origins of narrative, about the Odyssey and the idea of the basis of narrative being the retrospective telling of “what happened,” which coincides with Freud’s understanding that this is therapeutic. I guess that gets me to the psychoanalytic model but through a very different route.

TIMONEN: I’m curious what you mean when you say that psychoanalysts say things that novelists do not dare to?

CUSK: Oh, like reading Winnicott on motherhood: the mother hates the baby before the baby can know the mother hates him. I think there is a problem with writing in that the medium is very bourgeois and one is very conscious of the susceptibility of writing to be disapproved of, or disagreed with, in a way that visual art isn’t really. Psychoanalysis seems to offer a completely different road because there is no judgement, there is no: It’s so awful the mother hates the baby before the baby can know the mother hates him, because it’s taken to be an objective medical fact. And yet, what kind of fact is that?

TIMONEN: Jacqueline Rose mentions your book A Life’s Work, about the birth of your first child, in her book/extended essay Mothers, which questions society’s paradoxical conceptions of motherhood. I listened to an interview with her where, in addition to mentioning your book, she suggests that maybe the difficulty of expressing conflicted feelings about motherhood could in part derive from concerns about reinforcing negative stereotypes, maybe out of fear of compounding hatred against women/mothers – obviously it’s also about other things – but that maybe women are afraid of confronting this kind of ambivalence because of the need to keep up appearances of female unity …

CUSK: Yes, it’s violently suppressed.

TIMONEN: This reminded me of my own ambivalent feelings – not being a mother – about femininity in general, and I think a lot of women experience some type of hatred of femininity, but it’s a touchy subject because it’s hard to tell where to draw the line between internalized misogyny and justified hatred of something ideological and oppressive. And I was wondering if you thought there was a connection between ambivalence about motherhood, for example as you narrate it in A Life’s Work, and ambivalence about gender identity in general, or femininity in particular?

CUSK: I guess I think that motherhood, both in the reality of it and as a constructional discourse, is imposed on you. No matter how much you think it’s what you want to do, it’s still a thing imposed on you and within you. And I guess it could be said that gender is also that. I suppose my thinking never went in that direction. All I think now, I’m 52, is that the whole idea of gender being open to examination is just too late for me. It definitely would have changed me to know when I was younger that gender was, not optional, but that it could be broken. And maybe the same is true of motherhood and that’s why, in the end, though it was a vicious experience being criticized the way I was, I still think I was right to write my book. Anything that conveys the reality of a huge and life-changing experience that people assume they can go through unchanged – though you can’t ever really give anyone that understanding in words – maybe you can give more awareness that it is a choice. That’s the thing, having brought up two girls that are now young women, I’m still amazed at how veiled the whole idea of that choice is. Like that it’s a perfectly positive choice not to have children. That whole area is still very shadowy.

TIMONEN: There was an interview with you in Bomb magazine where I thought you said something really interesting. You described the methodology of your books Outline and Transit as one of reverse exposition, whereby the meaning of oneself is transferred onto the world, and you evoke this as a possible description of trauma. The specific words you use to describe this trauma are “loss of the subjectivity that generates assumptions of shared being.” This formulation made me think of femininity as something like an imposition of a shared being, and that having gendered expectations imposed on you, and this being specifically true of women maybe, is about the struggle of trying to be a subject but still always being taken as exemplary of your kind. And that, through that, you are being erased.

CUSK: Yeah, in the end, when you look back on it, you think: Why did I serve that stereotype? in whatever limited way. And I suppose that is an element of feminism’s repeated failure, that the stereotypes are still everywhere. I don’t think it is that difficult to bring up a girl/woman without those stereotypes, I hope I’ve done it myself, but the thing is that even if they are free of them, other people have them. All it takes is for them to get the wrong boyfriend and suddenly they’re criticizing themselves.

Anna Daucíková, „Seduction“, 1998

TIMONEN: This somehow, in my mind, also related to A Life’s Work, and the controversy around your account of motherhood, which expresses conflicted feelings. The book is so subjectively told, and it signaled so much to be about your specific experience; there is apparent an effort to claim that space for your subjectivity, which is then denied in the criticisms. And there is a kind of strange policing of experience, as if one’s experience of something could in itself be “wrong.” It is like an erasure of that asserted subjectivity. Do you think there is something about being a woman that could be equated with the kind of trauma as loss of subjectivity that you described in the context of Outline and Transit?

CUSK: All I know is that in the parts of life that have been determined for me, i.e., femininity, I’ve encountered injustice and dishonesty, and denial of individuality. As I said before, I was kind of fated to serve these subjects and it would have been much more fun probably to do something else that people found very pleasing. Is femininity inherently traumatic? I think in this day and age the difference is becoming increasingly clear between that being the case and it not being the case. For someone my age, our mothers very often had lives that were extremely different from how they expected our lives to be and indeed how our lives are, and they were then very angry with us for having lives very different from theirs. You are told two things: you’re told to be a woman and a man. I wrote a book about divorce called The Aftermath, and that was my theme in that, and how that double narrative in the end was capable of breaking all the long-standing arrangements between men and women. If you follow the logic through, marriage doesn’t work. It’s such a fascinating, moving spectacle. I’m old enough to have been a young woman in a very feminist moment, the early ’80s. It’s been astonishing to me to watch it go backward and backward and backward and now it seems to be sort of going forward. All it takes is a Donald Trump and suddenly you see the trauma of femininity and its completely compromised nature.

TIMONEN: There is something interesting to me about the way that writing that appears autobiographical, whether it is or not, solicits acrimony and protestation in its apparent “getting the facts wrong,” however subjective the account is. In my experience, there is this thing where people, readers, project themselves onto writing, perceive someone’s subjective account of their experience as an encroachment on their own reality. There is a kind of competition between the desires of the writer and those of the reader. I think that relationship is interesting: Is it a competition or perhaps synergy or reciprocity? Or some kind of negotiation? Do you project a relationship with your audience when you’re writing? If so, what kind of relationship?

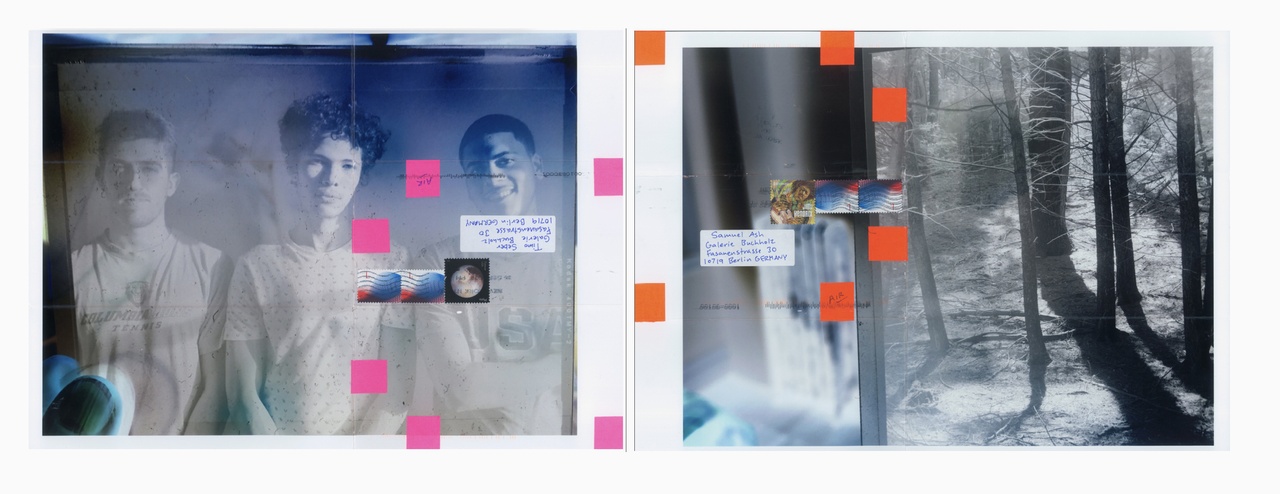

Moyra Davey, „Portrait / Landscape (diptych)“, 2017

The thing is, my interest has been in the novel. That’s where I started out, as a fiction writer. I suppose one value having children had for me was that while it’s an event one might think a woman writer would be swept off the map by, I had to earn the money for our household. I had to remain a writer and it became clear to me that the novel form couldn’t accept my experience, my voice as it was at that moment. There was no way my voice could speak through it so I thought, Memoir, that’s the place where I can say things in a different way. There are these parts of experience that are beneath the novel or just can’t fit into it. It became for me a dysfunctional form with many weaknesses.

The thinking that got me to Outline was: How can the novel receive this other reality, or parts of reality, without the blame for them being fixed back to the source? And yeah, that has a lot to do with how people read, what happens to you when you read. The main thing I thought about Outline when I finished was that it was unreadable. I looked at it and went sort of: Oh … I thought that was really interesting and I enjoyed writing it but nobody is going to be able to read it. It leaves these leaps for the readers to make, yet it seems that in that leap, which is essentially silence, is a non-stated part of the book. The reader makes a leap there. Something about that activity on the part of the reader and the silence on the part of the book put the responsibility for the material in the right place.

There is a need to blame and to disown what is true of you, which is a really basic thing that humans do when they lie, because they are very determined to deny parts of their own character. And that seems to me something that the reading process is riddled with. What you’d hope is that a book can get the better of that.

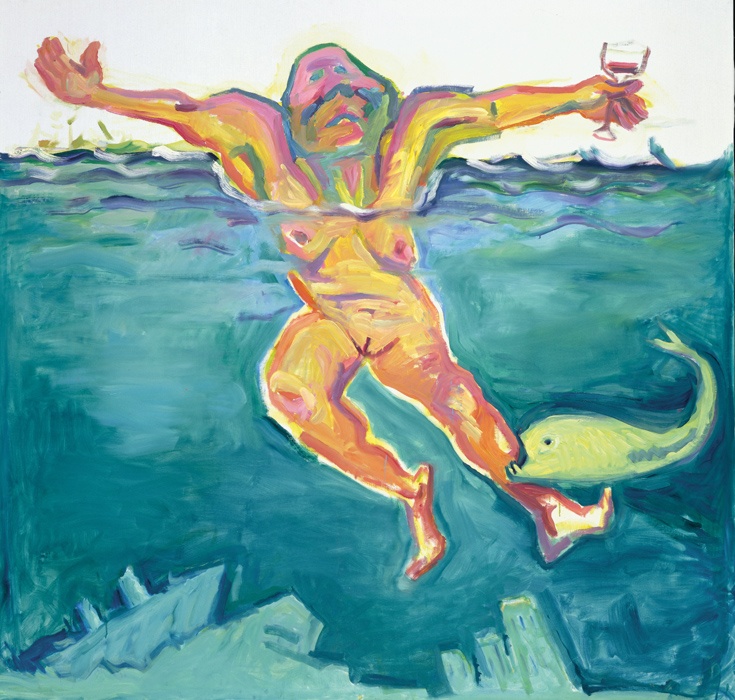

Maria Lassnig, „Die Lebensqualität“, 2001

TIMONEN: I read another interview with you where you were quoted as saying that you are not interested in yourself as a subject but as an object, and I wondered in what way do you see yourself as an object? As an object for yourself to observe or as an object to present to the outside world?

CUSK: I am interested in an example of something. I’m not interested in my own experience when I’m the only person who’s had that experience. Anything that is unusual or special about myself I’m not interested in at all. I always want to find my way to a shared junction with other people where they can recognize something, that I can say things out of my own experience that others can recognize. And that’s what all writers do. To me the whole debate about using one’s own experience is so ridiculous. It is such a completely bogus thing. The only reason we have to talk about these things is because novelists went off on this mad Hollywood narrative plot thing in the second half of the 20th century and that suddenly became the idea of what the novel was, that it had to have twists and turns and a plot. And that none of it had anything to do with you, it had no basis in lived experience. Well, that’s obviously completely ridiculous. Which does bring me to my current impasse, which is suddenly not being sure that any of my experience or me as an object is of any use to people, and that’s to do with the particular phase of life I’m entering. Which is kind of interesting, that there is nothing to say.

TIMONEN: In addition to a kind of objective tone the trilogy has, or an unmooring from the source, there is a kind of mirroring going on. Faye doesn’t have a voice because she doesn’t really say anything, and the people she encounters, who go on these monologues, don’t seem to have a voice either because they are constructed in this quite uniform language; one might read them as projection screens. There is something curious about this shared voicelessness in that it’s also not equal, there are some sort of relations of domination at play between Faye and the other characters, and it made me think they are somehow subsumed under Faye’s interiority, that they are somewhat dominated by her as well.

CUSK: In the end, what I’m doing is for me. It’s the end of omniscience, the end of saying that omniscience is a possibility. There can be no objectivity, there can be only be, even at its extreme, other people existing through one’s own perception. You notice certain things they say and not others, and those things are in fact reflections of yourself. So that is kind of me arriving at the end of the conventional novel. When you say these people speak the same, that’s been said a couple of times, and I completely understand why. It would be tiresome if every time a character presented themselves they enacted themselves in full form. Then you’re back in a Dickens novel, using a character, and having to serve them and having to be interested in them. The fact is when you read a novel it has a uniformity of tone: the prose. All I’m doing is taking the prose and putting it in the characters.

TIMONEN: There is a character in Outline called Elena who tries to conduct her relationships with men through a kind of forceful frankness, a way to protect herself from deceit through a kind of preemptive strike. And I found this character hilarious and really identified with her. She also struck me as being very dominating, and in some ways I felt she was engaged in this effort to control the narrative, which resonated with whatever dysfunctional thing it is that often motivates my own writing. Do these qualities of Elena have some specific significance for you?

CUSK: Well, that particular chapter, which is a very female chapter, is about precisely that: the attempt to control narrative, which the narrator is believing or hoping she’s moved beyond. There’s a definite feeling of that time in life, or phase of life, having gone by. Then the other character in that chapter is the poet, who is completely the opposite and just lets things happen to her. I very much wanted those ideas to be part of the conversation of the book.

TIMONEN: There’s something quite striking about the absence of consciousness, or feeling any need to reciprocate in your characters. The monologues seem slightly aggressive, and I wondered if you were specifically trying to write these characters with transgression or aggression in mind?

CUSK: I suppose sometimes, and in Kudos, toward the end, it becomes almost humorous. But I don’t think I felt that I was saying something about these people always talking about themselves, that’s not what my interest is. To me, this monologue is writing, and it’s what each person has. Writing a novel is a very specific thing, but this other writing is owned by each person. That’s what they’re doing. You can look at someone writing a novel as being an act of aggression, but it’s no different. It’s basically saying: Here’s my voice.

TIMONEN: Which relates back to psychoanalysis.

CUSK: Yes, it is indeed what psychoanalysis recognizes: each person’s sacred possession of a story. The story of them, their account, their voice.