THAT BELONGS TO ME! Reflections on Property and Value in Artistic Production

Theaster Gates, „Stony Island Arts Bank“, 2012

1. OWNERSHIP VERSUS POSSESSION

There are two respects in which works of visual art can be deemed to be property. Either their creators – the artists – like owners claim comprehensive command over them, usually however for only a limited period of time, [1] or the works of the artists pass into the possession of others, mostly private collectors or museums, who likewise declare them their property. In legal terms, possession and ownership do not here collapse into one category. Someone in possession of something is not necessarily its owner, as illustrated by the difference between tenants and owners so often mentioned in this context. The tenant is considered to be in possession of the apartment for a limited period of time, while someone else functions as its owner. In visual art, too, possession and ownership can be separated, such that while artists have since the 18th century had a right to the product of their labor as “intellectual property,” the product itself commonly passes into the possession of another. And going even further, it is for this new possessor vital that their acquisition can be tracked back to a (preferably renowned) creator. To a certain extent, their ownership is based upon the intellectual property of the artist, which is why works of art can be doubly marked as property. They embody, so to speak, the culmination of the logic of ownership. The desirability of possessing them only arises on the premise that they can be attributed to an author. Works of art can only circulate as objects of value if they are verifiably traceable to a single authorial entity. [2]

2. DUCHAMP'S MONTE CARLO BOND AS A PRIMAL SCENE OF ARTISTIC CRITIQUE OF PROPERTY AND VALUE

Numerous 20th-century artistic works revolved around the visual arts’ unique structures of ownership and value. In this context, reference is often made to Duchamp’s Monte Carlo Bond (1924) as the primal scene of reflection on ownership and value – a work that in fact represents a paradigmatic attempt to extend the artist’s ownership rights in such a way that the former still has the market value of their object at their disposal even long after it has passed into the possession of a third party. The possessor of this document, which oscillates aesthetically between bond and a portrait of Duchamp, was promised a share of 20 percent of the profits Duchamp aspired to make on a Monte Carlo roulette game by deploying a system. [3] Duchamp never made those profits, however, thus underlining the literally playful character of his work. The extent to which art-market transactions very much resemble a game of chance is also captured allegorically within this bond. It is at first glance comparable to a share in that its increase in value depends to a large extent on the plays (or moves) made by its issuer. But Duchamp – in contrast to a DAX company – takes the liberty of making a mockery of his security paper’s speculative logic. By never realizing the aforementioned profits, he utilized the “purposelessness” that has been claimed for artworks since the 18th century for his bond. The fact that it is Duchamp himself who is personally responsible for the future performance of his stock is also visually captured in the form of the artist’s portrait, taken by Man Ray. It depicts Duchamp as a Minotaur smeared with shaving foam; a hybrid creature that serves to symbolically represent the credibility of the security paper. While this document reminds us of the value-forming potential of a renowned artistic personage, it also and equally presents this figure as being less than credible in its insistence on ambiguity. Anyone who entrusts their money to this man (or, rather, the 500 francs that the bond cost) takes a considerable risk in doing so, as alluded to in the emphatically unserious-looking Duchamp portrait. At the same time, we are confronted with the idea of an extremely powerful artist: in Monte Carlo Bond, he is conceived as someone who is able to intervene in the value form of his product, as it is Duchamp himself whose refusal to play along undermines the speculative logic of his security paper.

This document is anything but a worthless bond, however. On the contrary: precisely because this work is traceable to an (at that time already legendary) artist named Duchamp, it has (concurrently with Duchamp’s advancing reputation) since become an iconic act of value-reflection, and was accordingly auctioned for a large sum at Christie’s in 2013. [4]

Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, „Monte Carlo Bond“, 1924

3. PROPERTY AS THEFT?

Artworks become things of value on the proviso that they circulate within a value sphere (the art market) as the original product of a unique creator. The signature serves here as proof of authorship; rather than referring only to the person of the author, it also binds the work and the author close together. [5]

Formulated in terms of categories of ownership, the signature is equivalent to making a claim. This seems to me to a be general characteristic in any assertion of ownership, since in order for something to achieve the status of property, it must first be marked and declared as such, [6] while in structural terms, the declaration of this claim comes at the cost of all those now unable to assert such a claim. Thus, behind every recognized author stand all those who were unable to speak up at that juncture or whose voices were overheard, excluded, or ignored. Authorship presupposes a freedom that is not available to everyone. [7]

The signature is therefore more than just a rhetorical signal used by artists to declare their authorship. It is the device via which the products of their labor are declared to also be something that originally belonged to them. On the one hand, this presumption seems necessary, since without it there would be no possibility of copyright; on the other hand, however, in structural terms, the legitimate claim to the fruits of our own labor comes at the expense of all those who lack the social conditions needed to make such a claim of ownership. Thus, even the form of possession indicated in intellectual property would involve a latent form of the “theft” that Pierre-Joseph Proudhon denounced with his renowned statement that “property is theft.” [8] While Proudhon’s stark equation might seem somewhat simplistic from today’s perspective, it nonetheless sensitizes us to the fact that something might have been taken away from others in the course of artistic appropriations. [9] In my opinion, however, the fact that intellectual property is not free of guilt does not mean that artists should abandon claims to possession of their products or ideas altogether. For one, experience shows that the production of possession and value in art functions in such a way that even attempts to undermine it are in fact caught up within it. Secondly, in a capitalist system, renouncing the claim to ownership established in authorship would run the risk of an artist’s labor remaining unrecognized and therefore unpaid – giving rise to endless potential for self-exploitation. And thirdly, even a radically proclaimed statement of exit from the value sphere remains within this sphere, at least for as long as artists continue to operate within a capitalist value system.

4. OWNERSHIP LOGIC OUTRUNS AUTHOR CRITIQUE

The author-critical artistic strategies of the 20th and 21st centuries have in truth been unable to eliminate the possessive thinking deeply embedded within the principle of authorship. In this context, one might think of those strategies of anonymity that in no way endanger the author-work ownership structure, as in the work of Banksy. On the contrary, it is precisely speculation about the true identity of this artist that has intensified the media interest around his product. The use of the name “Banksy” also ensures that the product produced under this moniker remains linked to a particular author. It belongs to him, even though we don’t know who the person behind this figure of Banksy really is. The numerous artist collectives that emerged in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, from General Idea to Clegg & Guttmann and Claire Fontaine, were also unable to avoid an implicit claim to ownership. The thesis could instead be put forward that collectives and collaborations lend further strength to the author principle, since they are perceived as metasubjects that promise an intensified exchange and lively works, thus increasing their attraction. [10] With hindsight, it must also be stated that the manifold forms taken since the postwar period by artistic procedures that critique the author principle have ultimately only served to expand and reformat artists’ claims to ownership of their products. When, for example, the authorial artist-subject was replaced by first aleatory and later algorithmic systems – as in the works of Ellsworth Kelly and, later, Cheyney Thompson – this was tantamount to deferring authorship to a system, and this deferral was always credited to its authors. Surrendering oneself to an external authority identifies an artist as a particularly potent author-subject. This also applies to the delegation of the painting process to assistants or employees – a process that no longer carries either the risk or potential for jeopardizing the principle of “authorship” and its assertion of ownership. While in the 1960s Andy Warhol still felt compelled to assure buyers of his silkscreen portraits that it was he himself (and not Brigid Polk) that had painted them, [11] artists such as Sarah Morris or Eliza Douglas can, thanks to the Conceptual turn, now have their pictures painted by others without endangering their own credibility. Anyone who claims the model of artist as entrepreneur for their own today also faces its pitfalls, however, such as the exploitation or potentially low renumeration of their employees. The price of departure from the romantic ideal of the artist is here visible in the mimetic alignment of the artist with a capitalist entrepreneur.

5. ARTISTS AS PRIVATE PROPRIETORS

The ownership claim that results from authorship is thus both a blessing and a curse. It appears to be as legitimate as it is problematic that artists claim ownership of the material and immaterial products of their labor, as this claim ultimately also means that artists resemble the type of private proprietor described by Karl Marx. [12] Like private proprietors, artists can also be described as persons broadly capable of determining the external conditions of their labor. The qualifier broadly is decisive here, however. In contrast to wage laborers, and to the creative worker of today, artists possess the products of their labor – it belongs to them, even – but only up to the moment when it is either given to a gallery on commission or sold. From that point on, the work of art detaches itself from the artist while at the same time continuing to refer back to them. Artists are thus private proprietors of a special type. But insofar as private property qua Marx implies relations of domination, visual artists would from this point of view be more on the side of the ruling class in structural terms. In terms of diagnosing the present moment, however, it must be conceded that the external conditions of artistic production since the 1960s have increasingly been determined by the market. We need only think of the increased competitive pressure in a global economy, of the normative power of market success in a competitive society, or of the obligation to be present on social media, where each and every thing is marketed in a profoundly personalized way.

Artistic practice is therefore increasingly subject to heteronomy, even while it still seems relatively self-determined when compared to general labor. [13] Attention has in recent years been drawn to this alignment of artistic and general labor, especially in the social sciences but also in art theory. [14] The finding here has been that the creative subjects now work within companies, with economic (or, to be more precise, speculative) thinking conversely having long since come to govern the artist’s studio. [15] As important as it seems, from my perspective, to investigate these overlaps between artistic and general labor, it seems at least as important to determine the differences that still exist between them. Ultimately, and unlike creative workers, artists can claim ownership of their product, albeit for a limited period of time. And even if this product passes into other hands, it still retains a reference to its author, the act of expropriation being as it is sweetened with money. The creative worker, by contrast, seeing themselves completely separated from the product of their labor, can only dream of such privileges.

6. LOSS OF OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL FANTASIES

While it is true that artists, as private proprietors, possess the product of their own labor, they can equally lose control over it. Collectors, for example, can in principle handle the product as they wish once it is in their possession. In the worst cases they can “flip” it by immediately reselling it at a profit, give it up for auction, present it in exhibitions without asking permission, or, should they choose, store it in a damp cellar – although, of course, gallery owners usually ensure that their buyers have a reputation for handling their acquisitions responsibly. In any case, there is at the time of the initial sale a far-reaching loss of control on the part of the artist over the product of their labor, a loss against which there has been massive resistance, especially in the USA in the 1970s. Probably the best-known attempt to regain lost control over the sold artwork is Seth Siegelaub’s The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement, a contract drawn up in 1971 for every artist to have their gallery owner and collector sign at the time of a work’s initial sale. Central to this agreement was the inclusion of the artist in each of the increases in value resulting from resale: per the contract, the artist would receive 15 percent of the increase in value each time. The collector or gallery owner lending their signature also undertakes to inform the artist of every exhibition of their artwork, while the latter has the right to borrow it if required. To make the matter palatable to gallery owners, artists were advised to give them a portion of the 15 percent increase in value. The clause not only covered sales but also the gifts and art objects frequently exchanged between artists, proving once more that the gift cannot so easily be removed from the sphere of economy and exchange. [16] Gifts change the value sphere through a logic of outbidding that has driven some people to complete ruin; however, the inherent shift of emphasis from material to spiritual wealth does not create an exit from the value system for the simple reason that it demands reciprocity and remains embedded in mutual exchange, as Marcel Mauss has shown in his study of non-European societies. [17]

John Baldessari, „Cremation Project“, 1970

In practice, however, Siegelaub’s regulatory attempt to put the informal economy of the art world on a contractual basis was ultimately unsuccessful. The muted response to this contract can be explained by the notorious resistance of art market stakeholders to any attempt at regulation. An art that is supposed to be “free” cannot be subject to regulation; it is hardly likely that any collector would want to see their rights to a recently acquired work of art restricted in such a way. This contract has not even been able to embed itself among artists, and it is to my knowledge used today only by Hans Haacke. That gallery owners have not agreed to this contract is self-explanatory: it creates the risk that already precarious deals could blow out immediately. And lastly, the administrative obligations imposed on its signatories have had a deterrent effect due to their time-consuming and costly nature.

Moreover, in my opinion, this agreement faces a more fundamental problem – a subject-theoretical one, as it were – in that it strives for the ideal of an artistic subject able to dispose both of itself and the circulation of its labor. In truth, the idea of a subject being “in control” in this manner is already a fiction from a psychoanalytical point of view. After all, the subject is per Freud not the master (or mistress) of its own house, as it is incapable of controlling its own unconscious. Of course, even an artist who is not in possession of themselves may intervene in the logic of the market, but at the same time, market events will always slip from their grasp, just as do those “ego boundaries” that are, per Freud, similarly fickle. [18]

From this perspective, the agreement represents a control fantasy that wildly overestimates the individual artist’s room for maneuver and underestimates the power of market structures. Individuals are not able to completely remove these structures, even by means of a contract. Perhaps it would have been more pragmatic to aim for a change of structures, instead of holding out the prospect of controlling distribution and circulation. Such control is bound to remain wishful thinking, not least because it presupposes a voluntaristic subject.

7. ARTISTS AS EXPROPRIATED POSSESSIVE INDIVIDUALISTS

Insofar as artists do not have complete control over either themselves or the ultimate fate of their work, they could be characterized as “expropriated possessive individualists.” Possessive individualism means that form of individualism that is orientated strongly toward possessions, and whose emergence C. B. Macpherson dates back to the 17th century. [19] Believing as they did in the worth and rights of the individual, liberal political theories of that period were based on the assumption that this individual would also be the owner of its own person. Macpherson describes how possession was resited within the nature of the individual and thus naturalized and legitimated. If the individual is then to be defined as a person in possession of themselves, then both the phenomenon of possession and the urge to possess appear as something entirely natural that necessarily results from the fact of their own individuality.

Theaster Gates, „Dorchester Projects, Chicago“, 2012

Artists thus have something in common with this possessive-individualistic subject, in that (as already described) they enjoy a greater power of disposition over both their work and thus over themselves in comparison to wage and creative laborers. But while artistic subjects may embody the prototype of a liberal subject, they have also and equally appeared – especially in the 20th century – as massively alienated subjects whose working conditions increasingly intersect with external economic and social conditions. It would be possible, here, to make reference to the historical avant gardes; Surrealism, for example, which invoked experiences of heteronomy and alienation, such as the model of écriture automatique. It was via this procedure that artists – typically male ones such as Breton and Éluard – aimed to systematically surrender themselves to an external authority, i.e., to pursue a form of self-expropriation. But as in Breton’s Nadja (1928), it was often a woman that served as a surface of projection for this new consciousness. The loss of the artist’s self here required a female sacrifice, with Nadja forced to suffer loss of the self and disorientation on behalf of the author. Insofar as it was a stream of unconscious that was supposed to dictate sentences to the practitioner of an écriture automatique, this practitioner no longer had complete control over themselves, instead deliberately surrendering themselves to another. But of course, this other also had to pay for their attempts at self-transcendence.

The many attempts by painters of the same period to symbolically relinquish control of the genesis of their paintings by having others sign them and fill the canvas – as exemplified by Picabia’s L’Oeil Cacodylate (1921) – likewise bear witness to an experimental arrangement of this sort, in which the artist purposefully relinquishes control and cedes it to another person – but on their terms. For in all these cases, it is the artist subjects who have determined the parameters (and limits) of their expropriation. And so it is that each of the experimental arrangements mentioned still ultimately stems from the initiative of an individual creator, who it is then subsequently credited to. The logic of possession therefore also takes its hold here. Does this mean that the logic of property cannot ultimately be escaped within the visual arts? And how could structures of ownership be shaped differently under such conditions?

8. BETWEEN PROPERTY DESTRUCTION AND VALUE SHIFT: BALDESSARI AND FRASER

Finally, I want to outline four exemplary artistic strategies that aim to change ownership and value structures without thereby striving to an imaginary world beyond the value sphere. As a model attempt at destroying property while ultimately seeking to increase its symbolic value, Baldessari’s Cremation Project (1970) must be mentioned here: per the aesthetics of early Conceptual art, he staged the burning of the paintings he produced between 1953 and 1966 as a ritual. [20] Despite the actual destruction of intellectual property, photographic documentation and relics of the action (a gravestone-like plaque and the urn containing ashes of the burned pictures shown in the exhibition “Software,” 1970) ensured that it was still possible to attach value to these material objects. The burning action was also announced in the form of a newspaper obituary (in the San Diego Union), with the symbolic death of the “old” Baldessari serving as the premise for his purified rebirth as a Conceptual artist. In a way, he changed with this from being one type of owner to another. Via the destruction of property, the artist thus asserted a new self-conception that purported to leave behind everything that had gone before. With the radicality of this gesture of destruction, Baldessari literally tried to erase his old identity, as if it were possible for a person to escape their own history. This staged break made future production appear more credible and thus potentially value-generating.

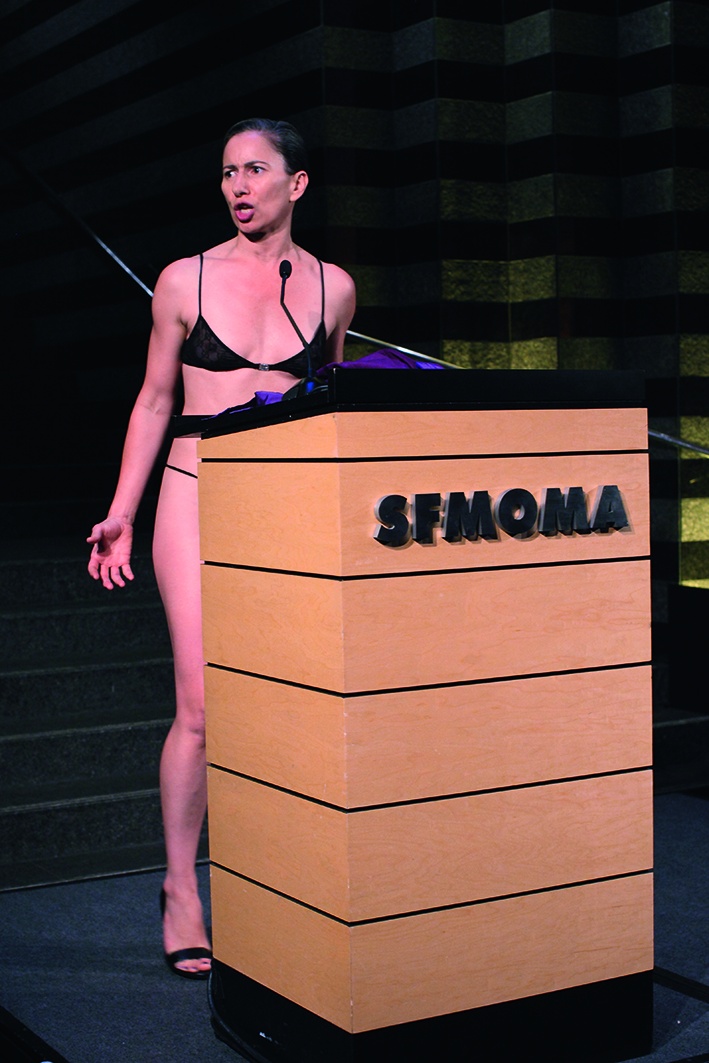

Andrea Fraser, „Official Welcome“, San Francisco Museum of Art, 2012, Performance

Performance art is usually associated with a far-reaching renunciation of value-generating products, whereby on closer examination, artistic performances (see Baldessari) usually provide relics or photographic/film documentation, i.e., “things of value,” even despite their ephemeral character. This also applies to Andrea Fraser, with the exception that in her case – apart from the video documentations of her performances – hardly any material works circulate on the market under her name. She has allegedly ceased working with US galleries since 2011, proving her disinterest in this form of commercial distribution. [21] Her labor is situated in a different value sphere – that of knowledge production – that is located between museums, symposia, exhibitions, academia, and publishers, and not in the sphere of auctions and art fairs. In her performances, it is her persona and body that stand in place of a value-generating product. Accordingly, it is possible to detect a certain fixation on her physical appearance; symptomatic of this was a recent New York Times Style Magazine feature in which it was approvingly noted that Fraser’s face is almost wrinkle-free. [22] What is decisive, however, is that unlike Anne Imhof’s performers, for example, Fraser’s body does not appear as a mute creature. From the very start, Fraser staged her persona as that of an intellectual who produces discourse – a social critic schooled in Institutional Critique. By building a bridge between body and mind and situating her performances in the museum world, she also ensured that her criticism of the belief and value systems of the art business was deposited where it belonged. The fact that her body functions within her performances as a value-generating resource becomes clear in the performances themselves, most impressively perhaps in Official Welcome (2001/2003), in which Fraser not only literally appropriated the language games beloved of those in the art world but also stripped down to a skimpy Gucci bikini at the end. This striptease left no doubt that in such performances, especially those by female artists, it is traditionally the female body that is carried to market to play the role of value object. Fraser’s far-reaching renunciation of value-generating products thus by no means amounts to a negation of the value form of art, but shifts it instead to the artist’s body. However, since this body also plants critiques of value into the value sphere, it cannot be reduced to its mere corporeality. Fraser has also intervened directly in the sphere of US museums, most notably in her most recent book, 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics (2018). Statistics here show that a high percentage of Trump supporters sit on the boards of US museums. In addition, Fraser demanded that these boards in the future no longer be staffed according to the criteria of money, a proposal that would lead to an actual change in the measurement and allocation of symbolic and market value within art institutions.

9. FAUTRIER'S ASSAULT ON THE ONE-OF-A-KIND, GATE'S OWNER-MIMESIS

Jean Fautrier’s Originaux Multiples could be described as a kind of precursor to appropriation art, hybrids of print and painting that vary his visual motifs and were finished with pastel, gouache, and his trademark “enduit” paste. While Fautrier produced these print-paintings for ten years between 1945 and 1955, partially as a reaction to the commercial success of his Otages images, they have received barely any attention within the field of art history. [23] According to his life partner, Aeply, Fautrier’s aim with these prints was to destroy the one-of-a-kind character of the artwork, including its price structure. [24] The Reproductions Aeply he produced around the same time likewise sought to undermine the value of the original by reproducing the images of successful fellow painters like Dufy, Derain, and Renoir in such a skillful manner that Braque apparently confused one of these prints with his own work. [25] Fautrier duplicated the images of those of his colleagues who emphasized the personal touch, with the results looking so close to the originals that they could be mistaken for them. It would even be possible to say that Fautrier’s painting-prints anticipated the strategies of artists like Sherrie Levine and Wade Guyton. They share with Levine’s Schiele works an interest in reproducing the original as mimetically as possible. And like Fautrier before him, Guyton also practices a form of print that does not exclude the artist’s singular interventions. But unlike Levine and Guyton’s work, Fautrier’s prints have been reduced to a footnote within his greater œuvre. [26] They also flopped commercially, possibly because Fautrier produced much more coveted one-of-a-kind paintings both before and after the print works that attracted all the attention for themselves. His attempt to leave the one-of-a-kind logic behind was outshined, to a certain degree, by his own one-of-a-kinds. Perhaps he was also not forgiven for producing the original works of his peers on an assembly line, and doing so in a way that made them appear decidedly painterly.

In the same way that Fautrier claimed the intellectual property of others for himself, Theaster Gates, in a quite different context, has played the role of an owner who nevertheless makes their property available to others. He bought and renovated empty buildings such as the Stony Island Arts Bank (2014), using them to hold exhibitions of contemporary black artists. He also used the buildings to provide public access to the collections and archives he purchased. What is interesting here is that he finances these kinds of inventions into urban space with his art productions. He has explained in an interview that ten percent of his studio time is spent on art production, which he then uses to fund his community activities, with the latter occupying ninety percent of his time. The proceeds of selling his artworks – such as his tar and roofing-paper surfaces – are thus used for projects intended for the benefit of others. And as the price for this redistribution of his income from art sales, Gates the artist also has to wear the hat of an investor/developer/project manager. Only in that he himself mutates into an owner and fundraiser can he use his property in keeping with his own beliefs – i.e., in a community-orientated way. Clearly, it is necessary to raise capital and deeply immerse oneself in the value sphere (in this case the world of real estate) in order to be able to assert non-economic criteria in determining the use of a building. Only via this investor-mimesis is Gates successful in shaping his project for the purposes of structural change to public space. The transition from his urban projects to the art world is anyhow fluid, as evinced by his archive of African American magazines like Jet and Ebony, shown in a commercial gallery (White Cube) in 2012. That the gallery was not permitted by Gates to sell this archive, however, does not mean that it is completely ejected from the value-creation process. [27] If anything, the gesture of preventing value generation here ensures that Gates’s other works gain in credibility, thus also potentially obtaining symbolic and market value.

With regard to the various ownership strategies of Gates, Fautrier, Fraser, and Baldessari, it can be declared that in the visual arts, any change in the structure of possession remains within the logic of intellectual property. This ultimately also means that artists are only ever able to change the value form of their product, without ever being able to entirely abolish it.

Translation by Matthew James Scown

Title Image: Theaster Gates, „Stony Island Arts Bank“, 2012

Notes

| [1] | It is of course also the case that the work may remain undiscovered or unsold, i.e., remain in the possession of the artist for their entire life. Proprietary possession gives way to third-party possession only on the condition that everything is functioning well in market terms. |

| [2] | This singular authorial instance can however also be a collective. On the connection between the unique character of the work of art and its specific form of value, see also Isabelle Graw, “The Economy of Painting – Reflections on the Particular Value Form of the Painted Canvas,” in: The Love of Painting: Genealogy of a Success Medium, Berlin 2018, pp. 316–33. |

| [3] | See Tobias Vogt’s text “Drawing Shares” in this issue. |

| [4] | See Vogt, “Drawing Shares.” |

| [5] | On the signature as the very instance that short-circuits the artist and work with one another, see also Karin Gludowatz, Fährten Legen, Spuren lesen. Die Künstlersignatur als poietische Referenz, Munich 2011. |

| [6] | On this relation between property and verbally made claims that must be clearly communicated, see also Carol M. Rose, Property and Persuasion: Essays on the History, Theory, and Rhetoric of Ownership, Oxford 1994, pp. 15–18. |

| [7] | And freedom today is, conversely, defined more and more via property, as recalled by Etienne Balibar. See Etienne Balibar, Equaliberty, Durham, NC 2014, p. 75. |

| [8] | See Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, What Is Property?, Cambridge, UK 1994, p. 13. |

| [9] | From a postcolonial perspective, Brenna Bhandar has shown the connection between property and colonial exploitation. See the interview with her by Daniel Loick in this issue. |

| [10] | On the artist collective as meta-subject and “surplus author” see also Isabelle Graw, “Still Lives: Expanded Authorship, Living Labor, and the Generation of Value,” in: Peter Fischli/David Weiss, How to Work Better, New York 2016, pp. 349–355. |

| [11] | See Andy Warhol/Pat Hackett, POPism: The Warhol Sixties, New York 1980, p. 240. |

| [12] | Karl Marx, “The So-Called Primitive Accumulation,” in: Karl Marx/Friedrich Engels, Collected Works, vol. 35, “Karl Marx – Capital Volume I,” London 1996, pp. 704–61. |

| [13] | On the heteronomy of artistic labor see also Sabeth Buchmann, “(Un-) Doing the Capitalist Self: Some Thoughts on the Meaning of Rehearsal and Learning Exercise in Melanie Gilligan’s Video Series Self Capital”; and Isabelle Graw, “Working Hard for What? The Value of Artistic Labor and the Products That Result from It,” both in: Isabelle Graw/Christoph Menke, The Value of Critique: Exploring the Interrelations between Value, Critique and Artistic Labor, Frankfurt/M. 2019, pp. 145–54 and pp. 155–61. |

| [14] | See Pierre-Michel Menger, Kunst und Brot. Die Metamorphosen des Arbeitnehmers, Paris 2002 and Ulrich Bröckling, Das unternehmerische Selbst. Soziologie einer Subjektivierungsform, Frankfurt/M. 2007. |

| [15] | On the association of artistic and general labor at the level of financial and artistic speculation, see Martina Vishmidt, “Speculation as a Mode of Production: Forms of Value Subjectivity,” in: Art and Capital, Leiden 2019. |

| [16] | See Kathrin Busch, Geschicktes Geben. Aporien der Gabe bei Jacques Derrida, Munich 2004 . |

| [17] | See Marcel Mauss, The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies, London/New York 2002. |

| [18] | See Sigmund Freud, “Civilization and Its Discontents,” in: The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works, vol. 21 (1927–1931), London 1961, p. 67. |

| [19] | See C. B. Macpherson, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke, Oxford/New York 1962. |

| [20] | See Cooje van Bruggen, “Interlude: Between Questions and Answers,” in: John Baldessari, Los Angeles 1990, pp. 11–68. |

| [21] | See Zoë Lescaze, “With Friends like These…,” in: The New York Times Style Magazine, International Edition, Holiday, December 7, 2019, pp. 58–63, here p. 62. |

| [22] | See Lescaze, “With Friends,” p. 58. |

| [23] | See Rachel E. Perry, “The Originaux Multiples,” in: Jean Fautrier 1898–1964, Yale University Press 2002, pp. 71–85. |

| [24] | Perry, p. 76. |

| [25] | Perry, p. 80. |

| [26] | Perry, p. 72. |

| [27] | Perry, p. 31. |