LEARNING FROM KIPPENBERGER?

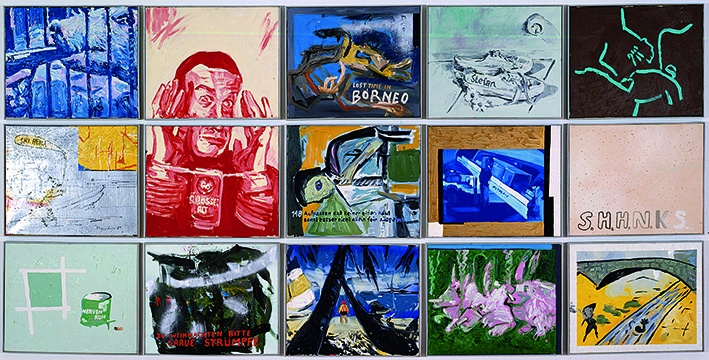

„Martin Kippenberger: Bitteschön Dankeschön. Eine Retrospektive“, Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, 2019, Ausstellungsansicht/installation view

Martin Kippenberger’s work is invariably read in reference to his life, often described as “excessive.” Since his death in 1997, he has been regarded as the epitome of the rule-breaking male artist who takes every liberty in his social behavior and art – for better or for worse. And in keeping with this, the retrospective currently showing in Bonn praises Kippenberger’s work for its “everything is possible and permitted” attitude – one from which contemporary artists could supposedly also benefit. Things are a little more complex, though: Kippenberger’s social presentation and art are so closely interwoven that it is impossible to avoid the fact that some of his jokes are cracked at the expense of others. However, his art does not merge entirely into the personal, as the numerous self-portraits in the exhibition demonstrate. Ambivalences are also created with the help of titles that generate contradictions and ensure his pictures and objects remain relevant from today’s perspective. It is especially when dealing with Kippenberger’s politically incorrect works, however, that it would have been vital, from my point of view, to recall the historical context in which they were created, and out of which they released their explosive power at that time.

Unfortunately, no such historicization takes place in this exhibition. It prefers to continue weaving a legend of the holy “Kippi,” instead of discussing the Kippenberger phenomenon as a set of problems. In the #MeToo era, for instance, the question immediately arises of how far the model of an artist who takes and permits himself everything remains acceptable. We also have to keep in mind how the model of the artist who commands each and every artistic freedom presupposes certain privileges – namely those of the white Western man. Ideally, however, these privileges are reflected upon and even ridiculed in Kippenberger’s work. One could therefore argue in his defense that his work shows both: the seductiveness of artistic freedom and the precarity, violence, and grotesqueness of such an ideal. But wherever his artistic freedom results in a freedom to humiliate others – mostly those weaker than him – this freedom has become questionable, especially in the era of online trolling.

During his lifetime, Kippenberger himself ensured his work would be strongly linked to his life by directly using his own life experiences, such as getting drunk or being beaten up, for early images from the 1980s, such as Alkoholfolter (Alcohol Torture, 1983) or Dialog mit der Jugend (Dialogue with the Youth of Today, 1981–82). Enriched as they may have been with “life,” they cannot be reduced to it. His self-portraits from the Hand Painted Pictures series (1992), for example, overwhelmingly invoke painterly conventions, from Gustave Courbet’s squat bodies to Francis Bacon’s image composition. In these portraits, Kippenberger’s strangely shortened figure mutates into a colossus of loosely applied paint – with just his head having been painted with caricaturing realism. The life in these pictures proves to be one that has been highly aesthetically mediated. Given that we cannot equate product and person when it comes to Kippenberger, we cannot separate the two from each other either. They are interwoven without precisely overlapping. This is why we have to address his sometimes politically incorrect rhetoric while refraining from jumping to conclusions about his alleged “character.”

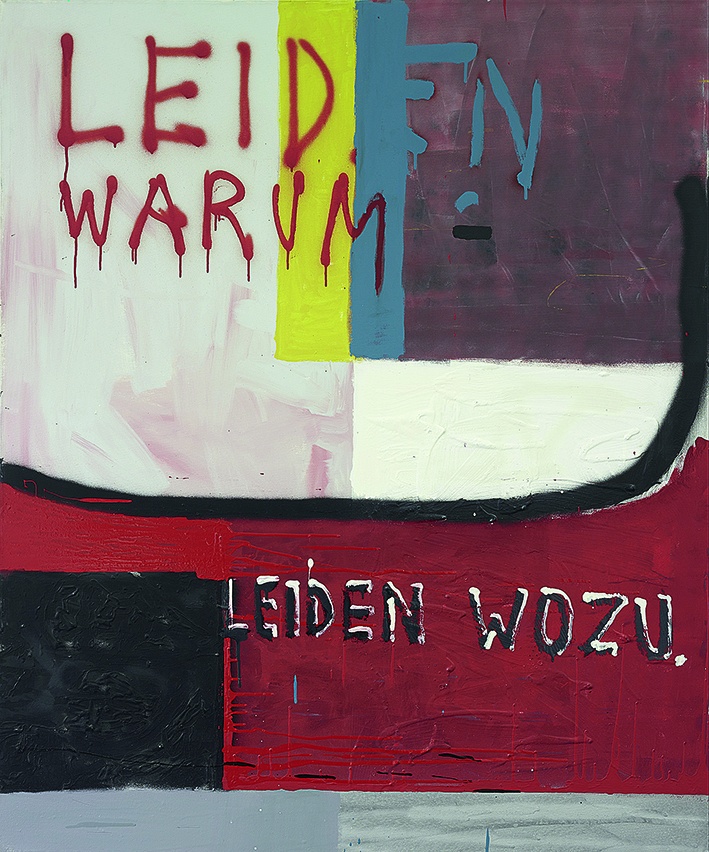

Martin Kippenberger, „Leiden warum – Leiden wozu“, 1982

With its title, “Bitteschön Dankeschön,” this exhibition is also oriented toward Kippenberger’s work’s emphasis on life: the title reproduces a bon mot of the artist from a painting in the Fred the Frog series (1989–90). It shows the artist’s body, turned upside down and crucified, once again as a fleshy mass of color, united in a kiss with the figure of death. The quasi-religious concept of the artist who gives everything (“bitteschön,” you’re welcome) and sacrifices himself for us (“dankeschön,” thank you) is both invoked and mocked in this self-portrait: the artist here is a reptile-like creature hanging upside down on the cross. But the fact that the exhibition, per its own title, forms its program based on one of the artist’s numerous mottos is also a symptom of the perspective chosen for the show. It is in its proximity to its subject that I see both the strength and the problem of this exhibition. While its closeness to Kippenberger permits new insights, this retrospective also tends to uncritically affirm its object.

Conventions do not apply to Kippenberger. Disrespectfully and without regard to damage caused, he consistently appropriated everything artistically: from “I love” stickers, the input of his assistants, and motifs from the Russian avant garde, through Dadaist text-picture games and right up to hotel stationery, Picasso’s widow, and Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa. With wonderful regularity, he also took the liberty of having others – professional sign painters or assistants – paint his pictures, without this ever endangering the principle of his authorship. On the contrary: even delegation fulfills the potential of the principle of authorship. Like Warhol, Kippenberger belongs to those meta-artists who transform the work of others into extra value for their own work. As an example of the model of the artist as entrepreneur, his work exhibits both the advantages and the pitfalls of this model.

His frantic appropriation is always most impressive when he poses the literal question of whether this is still even “art.” Kippenberger’s best paintings and objects question the consensus of what “good art” is. A rarely shown image from the 1993 series Erfindung eines Witzes (Invention of a Joke) shows a sole pecking chicken in a field that is smeared in yellow and black and full of grains that resemble coins. Per the German idiom “Auch ein blindes Huhn findet mal ein Korn” – even a blind chicken finds the occasional grain or, more idiomatically, every dog has its day – and in its aesthetic poverty, it is a late-era “bad painting” that still manages to subvert the criteria for a good bad picture. It demonstrates that only a few marks are needed on a canvas for it to pass as “painting.” Here, the liberty Kippenberger takes is that of undermining embedded aesthetic standards.

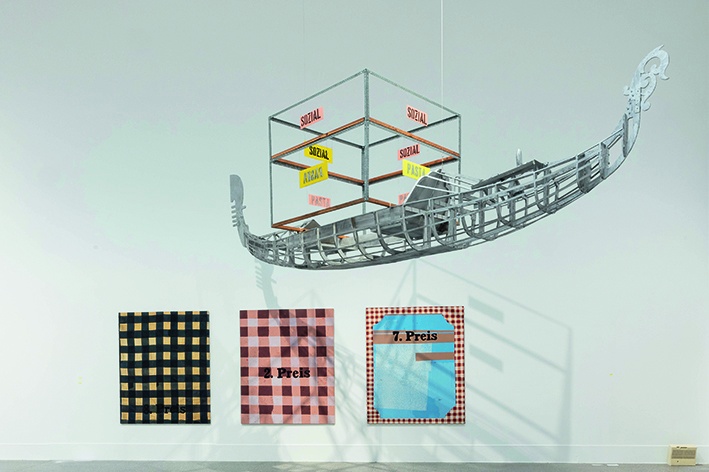

„Martin Kippenberger: Bitteschön Dankeschön. Eine Retrospektive“, Bundeskunsthalle Bonn, 2019, Ausstellungsansicht / installation view

The question of value, including in the sense of a polarity of symbolic and market values, is a thread running through his works: starting with the grandiose Ertragsgebirge (Profit Peaks, 1985) images, which lead ad absurdum the economic notion of a measurable and depictable yield with the help of pseudo-graphically painted structures, and continuing with the Preisbilder (Price Pictures, 1987) series, which demonstrates the arbitrariness of prices that are not even plausible in the pictures themselves. Why should one price picture, 7. Preis (7th Price), with its red-and-white checked fabric as the base of the image, rank higher in the hierarchy of values than 2. Preis (2nd Price), the one with the painted grid and oats interspersed among its colors? In Kippenberger’s case, the value of an image is not something that can be found in the image itself. Value appears as something utterly social. Even though Kippenberger claims the privileges of a white male artist, he by no means presents himself as a sovereign subject. Rather, he stages himself as a broken, damaged figure, as if to indicate the other side of this ideal of freedom. Even the berserk artist with his provocative attitude pays a high price. To present oneself as Picasso’s desolate successor with a beer belly and boxer shorts, as Kippenberger does in his self-portraits, has in art history rather been the prerogative of male artists – save for a few exceptions such as Alice Neel or Maria Lassnig. But as a rule it has been men, from Duchamp to Polke, who have been able to symbolically endanger their roles, because they did so from a socially secure position.

Kippenberger also provided plenty of material that fed into the art world’s desire to produce “artist legends.” But as much as he seems to have taken it on himself to play the role of the suffering artist, he also ridiculed this myth in a way that is still relevant today. One example would be the 1982 work that presents a dissolving field of colors daubed with the adage “LEIDEN WARUM – LEIDEN WOZU” (SUFFER WHY – SUFFER WHAT FOR). Suffering is here indeed declared to be something unavoidable, something that belongs to the image. The question of why is one that Kippenberger ultimately leaves open, rendering the suffering senseless. As an artist, you obviously have to produce material for legends, even when you no longer believe in them.

In keeping with the myth of the male genius, Kippenberger’s women generally stand for the other. Either they are glorified, as in the colorful and masterly Jacqueline paintings (Jacqueline: The Paintings Pablo Couldn’t Paint Anymore, 1996), or “woman” is the source of problems, as in Eifrau, die man nicht schubladieren kann (1996). In the Jacqueline paintings, Kippenberger occupies both Picasso’s position and that of his muse, Jacqueline: he created the portraits of the grieving widow as a surrogate for Picasso, while also signing them with “JP” – Jacqueline Picasso’s initials. He was, of course, not the first male artist to wish he was Picasso and at the same time seek to claim the female sphere of reproduction for himself. Something else is happening with the painting Eifrau, die man nicht schubladieren kann. The work’s title – Egg Lady Who Can’t Be Pigeonholed – declares that the egg woman cannot be classified. Which is then disproven by the painting itself: it shows a female figure as an egg-shaped body that includes a drawer, once again reducing “woman” to her fertility (in the form of an egg). It was evidently hard for Kippenberger to see women as anything other than marked by their gender.

The liberties taken by “Kippi” occasionally result in politically incorrect works, some of which can be found in the exhibition. For example, the pair of columns – one black, one white – titled Love Affair without Racism (1989), the name suggesting a non-racist romantic attachment. Should the anthropomorphic columns tell us that the reflexive reduction of a person to their skin color is racist, or is the work itself responsible for a racist reflex of this kind? Images like Bitte Brigitte spinn nicht rum! (Please Brigitte, Don’t Spin Out!, 1981–82), on the other hand, recall the sexist humor of the 1980s: a friend (named Brigitte) is declared to be a hysteric who has to be discouraged from “spinning out.” In the early 1980s, Kippenberger was not alone in using this kind of old-man humor. In the German art world of that era, the lessons of the women’s movement were flatly ignored and the agenda was to either devalue the production of women or ignore it altogether. Kippenberger was associated with a group of male artists – Albert Oehlen, Werner Büttner, Georg Herold, Günther Förg – without the exclusiveness of this male group having been addressed as a problem. This would change in the early 1990s with the emergence of so-called context art and greater reception of feminist and postcolonial theories. And this increased sensitivity to mechanisms of exclusion in the art world was not something that escaped Kippenberger’s attention. He became interested in the work of his Conceptual colleagues, such as Louise Lawler and Andrea Fraser. Methods such as research and Institutional Critique began to take up more space in his work. Examining the context from which the work emerges is also helpful when it comes to explaining a painting such as Heil Hitler ihr Fetischisten (Heil Hitler You Fetishists, 1984), which hangs somewhat hidden away in a corner of the exhibition. With its depiction of a bandaged arm that, despite injury, is reflexively stretched out in a Hitler salute, this painting is directed against the continued latent existence of Nazism’s legacy in West Germany. It also mocks those collectors and gallery owners in the art world who loved male artists largely for their transgressive behavior, driving them to violate taboos. Today, when AfD deputies with völkisch beliefs are sat in the Bundestag and right-wing radical ideas are becoming socially acceptable in middle-class society, work of this kind would lack the thrust it originally had. It must be feared that it would today again be praised for breaching taboos, namely those of political correctness. And this praise would be offered by those who genuinely believe that free speech is under threat. In fact, the inverse is true, as can be seen from the recent increase in taboo-breaking racist, sexist, and anti-Semitic pronouncements. Given such circumstances, political correctness advocates for things worth supporting: equal representation and greater sensitivity to the violent potential of language.

„Martin Kippenberger: Bitteschön Dankeschön. Eine Retrospektive“, Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, 2019, Ausstellungsansicht / installation view

It would have been a significant gesture if the exhibition had contextualized those works that flirt with political incorrectness, especially in view of those members of the cultural sphere who, invoking the phantom of an allegedly ubiquitous “PC terror,” support provocations similar to those of Kippenberger. What the exhibition’s curator, Susanne Kleine, has succeeded in doing is rather to illustrate the inflationary mode of production through the dense exhibition of rarely shown paintings, such as the Don’t Wake up Daddy series from 1994 and the Erfindung eines Witzes (Invention of a Joke) paintings from 1993. More has always been more with Kippenberger (for example in his dense and witty Peter installation from 1987, in which furniture-like objects, including a grey painting by Gerhard Richter used as a tabletop, are stood closely together). With the exhibition space permitting a fluid transition between the various phases of his work, Kippenberger’s career-long interests and aesthetic processes emerge with clarity.

He was fascinated by the idea of the avant garde and held a belief in the social function of art. Numerous paintings from the 1980s, such as Kulturbäuerin bei der Reparatur ihres Traktors (Cultural Revolutionary Peasant Woman Repairing Her Tractor, 1985) or Werktätige Bevölkerung kurz vor der Mittagspause (Working People Shortly before Lunch Break, 1984), revolve around the utopia of a workers’ and peasants’ state. It is not surprising that Kippenberger was interested in the avant-garde project of bringing art into life, given the numerous references to life in his work. But unlike artists like Joseph Beuys, who he frequently referred to, Kippenberger did not want to overcome the art/life dichotomy. On the contrary, his naively and drably painted warehouse architectures leave no doubt about the dubiousness of an art that places itself in the service of society. The way “art“ and “life” intertwine can also be seen in the drawings of the Input/Output series (1986–92): they are enriched with Kippenberger’s various living spaces, the ground plans of which he reproduced from memory, however. They are thus aesthetically mediated, fictitious psychological spaces that give us no real information about his life circumstances. Here too, art does not merge with life; and conversely, it is not an authentic life that we find in his art. In any case, Kippenberger was increasingly critical of the “avant-garde” principle, as proven by the work Das Ende der Avantgarde (The End of the Avant-Garde, 1988), which is also shown in the exhibition. Numbers (1, 2, 3, 4) attached to stenciled-out wooden balloons indicate that the avant garde has been numerated. Its hour has come, and it is only from this disillusioned perspective that its current potential can be gleaned. Of course, this also applies to the Kippenberger phenomenon itself: in the course of its historicization, we can differentiate between those approaches that are still useful and those that are politically questionable. It is precisely because Kippenberger’s status now resembles that of his alter ego Picasso that we can, per John Berger, freely identify both the successes and failures of his work.

“Martin Kippenberger: Bitteschön Dankeschön: A Retrospective,” Bundeskunsthalle Bonn, November 1, 2019–February 16, 2020.

Translation: Matthew James Scown

Note

This is a longer version of the text “Picasso mit Bierbauch,” which appeared in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, November 17, 2019, p. 36.