THE LIMITS OF REPRESENTATION The Ruhrtriennale and BDS

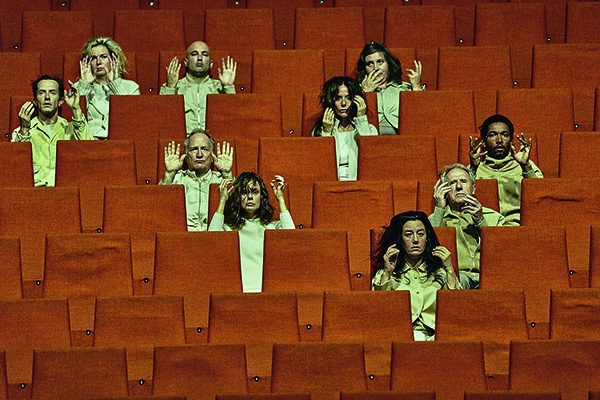

Christoph Marthaler, „Nach den letzten Tagen. Ein Spätabend“, Ruhrtriennale, 2019

On April 22 the Ruhrtriennale – an international festival that since its launch in 2002 has been repurposing the Ruhr area’s machinery, blower, and turbine halls, now no longer profitable in the extraction of raw materials, for dance and musical theater, concerts, and also at times for drama – issued a press release announcing that the 2020 edition would not take place “due to the corona pandemic”: “The health of the audience, the artists, and staff is the absolute priority.” An international festival in large halls can of course become a center of infection. At the time the cancellation was announced, large events were banned in Germany up until August 31, and the festival was planned for August 14 to September 20. However, the artistic direction team led by Stefanie Carp – as with almost all other festivals and institutions – was already working on a plan B which would have made a modified or downscaled version of the festival possible, in keeping with the pandemic-era hygiene regulations.

Together with colleagues in media studies, we at the Ruhr University’s Institute for Theatre Studies had organized a conference the previous year in partnership with the festival and were observing events very closely. Similarly to many other observers of the scene, I could not help but assume that the total cancellation was related to the acrimonious discussions regarding the person invited to give the opening speech. It was to have been given by the philosopher Achille Mbembe, who with Critique de la raison nègre (2013) – translated into English as Critique of Black Reason – has presented a much-read work of postcolonial theory. In his book, Mbembe explains that the “nègre,” first produced as such in modernity, “is the only human in the modern order whose skin has been transformed into the form and spirit of merchandise – the living crypt of capital.” And despite or even because of this, there is the hope that through the nègre, “a humanity reconciled with nature, and even with the totality of existence, would find its new face, voice, and movement.” [1] Ultimately, he pleads for a universalist perspective and “reparation” of the world. [2]

When word spread of the invitation, a parliamentary delegate of the Landtag – Lorenz Deutsch of the Free Democratic Party – wrote to Carp that despite his huge “anticipation” for the festival, he wished to ask for “an urgent rethink to the invitation,” as Mbembe was a “signatory to the BDS call for the academic boycott of Israel.” Deutsch cited sections of Politiques de l’inimitié (2011) (published in English as Necropolitics), [3] in which Mbembe contrasted South Africa’s apartheid regime and the Israeli occupation: “However, the metaphor of apartheid does not fully account for the specific character of the Israeli separation project,” wrote Mbembe. “In the first place, this is because this project rests on quite a unique metaphysical and existential basis. The apocalyptic and catastrophist elements that underwrite it are far more complex, and derive from a longer historical horizon than those elements that used to support South African Calvinism.” [4] The objection can be made that it is not only the Israeli “project” – should we wish to call it that – that feeds on deeper-lying resources but rather the entire complexity of the situation in the Middle East, where fears, aspirations, and hopes of salvation overlap and confront each other across three monotheisms. A little later, Mbembe makes an extra-historical connection between the Israeli occupation and other forms of “fantasy of extermination” [5] such that cannot be recognized in the actions of the Netanyahu government even with the worst will in the world. Mbembe seems likewise to have little interest in the fact that the nation state of Israel is a safe haven for Jewish minorities around the world.

Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, „Menschen am Sonntag“, 1930, Filmstill

The debate picked up pace. During its course, it emerged that alongside writing a preface for the 2015 edited collection Apartheid Israel, Mbembe had also actively taken part in the 2018 disinvitation of the Israeli peace and conflict researcher Shifra Sagy from a conference (whose Palestinian project partners had likewise been attacked by BDS supporters). The Frankfurter Allgemeine and Die Welt on the side of anti-Mbembe critics and Deutschlandfunk Kultur on the side of Mbembe’s defenders overflowed with new articles (with Die Tageszeitung, among others, between the two fronts). Mbembe demanded an apology from Felix Klein – the Federal Government Commissioner for Jewish Life in Germany and the Fight against Anti-Semitism, who had accused him of trivializing the Holocaust – and threatened legal action. The supervisory board of Kultur Ruhr GmbH called a special meeting, with the mayor of Bochum taking the floor to declare that BDS could be allowed no place in his city. In an April 23 article for Die Zeit, Mbembe stated that he regards Israel’s right to exist as “fundamental to the equilibrium of the world.” [6]

There was a notorious prequel to the affair: in 2018, the band Young Fathers had been invited, disinvited, and re-invited to the Ruhrtriennale before cancelling their appearance themselves, thus almost bringing the entire festival to the brink. Young Fathers had communicated their open support for BDS. More concretely, in 2017 they had cancelled their appearance at Berlin’s Pop Kultur festival, as the Israeli embassy had paid a €500 (!) travel grant to a participating Israeli artist and was thus listed as a cooperation partner. Armin Laschet cancelled his participation in the opening. And the journalist Stefan Laurin, who later drew Deutsch’s attention to the Mbembe invitation, attacked Carp virulently via the Ruhrbarone website. Malca Goldstein-Wolf wrote a protest letter.

Hosting the Ruhrtriennale became a stress test for the team, and the emotionally charged issue was highly present in emails and social media. The festival then showed works by Christoph Marthaler, Sasha Waltz, and the magnificent play No President from New York’s Nature Theater of Oklahoma; Laurie Anderson appeared at the Lichtburg in Essen.

The following year – 2019 – we at the Institute for Theatre Studies were asked by the chancellor of the Ruhr University if we would be able to offer our teaching support at the huge Audimax lecture hall for the planned production of Marthaler’s Letzte Tage. Ein Vorabend (Last Days: A Preview Evening) – now retitled Nach den letzten Tagen: Ein Spätabend (After the Last Days: A Late Evening). In the piece, which was then performed on August 21 as the festival opener, a fictitious parliament meets in the distant future and celebrates the recognition of European racism as part of the world’s cultural heritage. The brutalist construction of the Audimax, whose interior could well have been designed by Anna Viebrock, served as the world parliament. The performers deadpanned various speeches, such as those from 1894 by the mayor of Vienna Karl Lueger and from 2007 by the FPÖ politician Susanne Winter. Luigi Nono’s “Ricorda cosa ti hanno fatto in Auschwitz” is heard while the performers sit scattered across the seats of the empty auditorium, mouths torn open in silent screams. At the end, with Felix Mendelssohn’s “He That Shall Endure to the End, Shall Be Saved,” the sound fades slowly away while the choir disappears into the building’s invisible corridors.

In the run-up to this performance, we began a collaboration with the Ruhrtriennale. I had already been planning readings on representation, with other seminars addressing postcolonial constellations and the politics of appearance per Hannah Arendt. In talks with Carp’s team, we also agreed that the Ruhrtriennale would host a symposium with invited guests, with students also presenting academic papers based on the events. Astrid Deuber-Mankowsky, Leon Gabriel, and I arranged the symposium program with the support of the dramaturge Julia Naunin; it was entitled Limits of Representation, with the Ruhrtriennale adding the subheading Crisis of Democracy. When a short time before the conference Jacques Schuster announced in Die Welt of Cilly Kugelmann – our invitee and former curator of the Jewish Museum Berlin – that “employees of the museum say she is close to some ideas of the anti-Israeli boycott movement BDS,” [7] we prepared for various scenarios. But the only people to turn up were our own students, colleagues from other departments, and a few Bochum residents with an interest in culture.

WestEastern Divan Orchestra mit Daniel Barenboim, 2018

Our declared goal was to not wage any proxy wars on stage – neither like BDS or about BDS. Within the Turbine Hall of the Jahrhunderthalle Bochum, we wanted to investigate, in a way in keeping with an engine room, how representations are produced, who is even allowed and who is not allowed to step on the stage of representation, what excluding or normative functions representations have, and why they are nevertheless indispensable. The anthropologist Rosalind Morris of New York held a brilliant lecture, “Notes from the Anticolonial South,” and introduced listeners to Ishmael Reed’s The Terrible Twos and Black Sunlight by Dambudzo Marechera, with a podium discussion seeing Cilly Kugelmann explain her work at the Jewish Museum in extraordinary nuance. Other lectures discussed Walter Benjamin’s “Critique of Violence” (Deuber-Mankowsky), Arendt’s chapter from Origins of Totalitarianism on the rightless (Bettine Menke), and the role of demagogues in the Athenian polis (Julia Stenzel). I spoke with Stefanie Carb about the selection of texts for Nach den letzten Tagen and about the Neue Rechte (New Right) movement.

Later, the annual Ruhrtriennale Festival Campus took place, bringing together international students. That year, directed by Philipp Schulte, a collaboration with Nikolaus Müller-Schöll of Goethe University Frankfurt was the source of special funds for organizing a PhD student workshop beyond the borders of Europe. Thus PhD students from the University of Chicago under the direction of David Levin and from the University of Tel Aviv under the direction of Daphna Ben-Shaul and Dror Harari also participated. Ben-Shaul visited our Institute for Theatre Studies again in the winter semester, holding a lecture on the founding of the Israeli state with Jacques Derrida’s “Declaration of Independence” as its starting point, while also covering Israel’s founding as reenacted by the Tel Aviv performance group Public Movement and the Sala-Manca duo of Jerusalem, who developed installations. We had extensive discussions, among other things regarding the concepts, which may need distinguishing, of the American “people” as constituted only at the time of founding, and the Jewish “people.” An excursion to Tel Aviv planned by the Institute to follow the visit was postponed due to the pandemic.

In the debate about Mbembe, the irreconcilable fronts once again boiled over. I have always wondered about the cause of BDS activists’ focus on Israel. While I do not wish to presume to pass verdict on Jewish intellectuals like Judith Butler and Eyal Weizman – the arguments here on the role and function of the Jewish state going much deeper, the connections and personal influences being complex and, individually, to be taken seriously – it has always been unclear to me why philosophers, literary theorists, and also musicians and artists are interested to a lesser degree in the destruction of entire habitats due to global extraction, in slavery-like working conditions in Arab countries, and in zones entirely forgotten by the Western world, such as central Africa, and rather in a democracy that, despite having for over ten years been ruled by a right-wing, nationalist government has not yet, even with all its repressive rule, succeeded in eliminating the representation of Arab Israelis in the Knesset.

But I am just as disturbed by the uniquely self-assured German attitude towards postcolonial voices, an attitude of which the anti-Semitism researcher Felix Axster rightly described as “provincial” [8] in a Der Freitag article that is very much worth reading. Klein, the Federal Government Commissioner for Jewish Life in Germany and the Fight against Anti-Semitism, joined the March of Life run by TOS Dienste Deutschland – a fundamentalist evangelical association that demands all Jews to return to the Holy Land so Christ may reappear and finally convert them. [9] The self-same Klein later explained in a Die Zeit interview that one question must be reformulated: “Namely the question of postcolonial studies and its relationship to anti-Semitism. It is very much clear that some of these theories collide with our Erinnerungskultur [culture of remembrance, here specifically of the Holocaust], a culture I consider to be an accomplishment.” [10] It is certainly absolutely correct that, as Axster writes, “colonialism and Nazism are not one and the same.” [11] To relate this back to Mbembe: the nègre is not “the only human” whose flesh has been made into merchandise. [12] The various forms in which violence is experienced can thus by no means be equated, but it is necessary to differentiate the discourses that have justified and generated suffering. We could then either, per Axster’s hope, “declare that a space is opening up in which the possibility is on hand of relating specific, traumatic experiences of violence to each other, ideally in empathy and solidarity” – or we could, as Axster has it, “slam the door.” [13]

Klein’s labelling of the – never-concludable – processing of the Holocaust as “our Erinnerungskultur,” however, points to the problems within his argumentation. To the degree that “our Erinnerungskultur” is celebrated as an “accomplishment,” there is danger of a marked satisfaction with that which has been achieved so far, thus making any further critique unnecessary. The historical responsibility for the “final solution to the Jewish question” is indeed vast and historically unique. But Germany also played a highly violent role in Africa, be it in the fateful introduction of racial doctrine in Rwanda, the genocide committed against the Herero and Nama in Namibia, or as the host of the Berlin Conference – also called the Congo Conference – in 1884. As stated above, the issue cannot be one of the comparability of experiences of violence, and it is certainly not the role of the descendants of offenders to decide upon whether they can emphatically be placed in relation to each other. This is a decision which lies with victims and their descendants. Germans of all people should not give themselves the task of making clear judgments about Israel, Palestine, and the representatives of postcolonial discourse. I support Angela Merkel in her description of Israel’s security as “non-negotiable” [14] in 2008. This is a position I always argue in discussions. Beyond this, I try to show humility and caution, and to listen. Whatever thoughts we may have about the invitations and disinvitations: in its stronger moments, like the festival campus discussions, the Third Space, or Faustin Linyekula’s Congo (2019), the Ruhrtriennale offered such a place for listening.

The Ruhrtriennale will not take place this year. A new three-year cycle will commence next year, with a new artistic director. The festival – since its inception having been driven by the already-problematic regional project of transforming animal-bone-crushing machinery of extraction into “cathedrals of industrial culture” – has become mixed up in the evidently aporetic discussions of Middle East religion and politics. I myself wish to continue heading into the engine rooms with thinkers from Israel, the US, and Europe, but ultimately also with more from Africa and Asia; with humility and curiosity, listening and asking questions. As part of this, we can read and critique Mbembe, and also invite him and ask him directly – interestingly something which Shifra Sagy, boycotted by Mbembe, has pleaded for. [15] We should certainly continue reading Karl Marx; Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze; Jacques Derrida and Gayatri Spivak; W. E. B. DuBois, Aimé Césaire, Stuart Hall, and Frantz Fanon; Silvia Federici, Angela Davis, bell hooks, and Saidiya Hartman; Freddie Rokem, Daphna Ben-Shaul, and Dror Harari; alongside Felwine Sarr and Judith Butler. We should, no matter what, try to keep the conversation happening.

Translation: Matthew James Scown

Notes

| [1] | Achille Mbembe, Critique of Black Reason (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), p. 6. |

| [2] | Ibid., pp. 180–183. Mbembe here plays with the dual meaning of “réparation,” as both repair and reparation(s). |

| [3] | Deutsch quotes the second chapter of the book: “The Society of Enmity”: https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/the-society-of-enmity. |

| [4] | Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), p. 44. |

| [5] | Ibid., p. 45. |

| [6] | Achille Mbembe, “Die Welt reparieren,” Die Zeit, no. 18/2020, April 23, 2020. |

| [7] | Jacques Schuster, “Sinnbild und Opfer eines deutschen Misstands,” Die Welt, June 28, 2019 https://www.welt.de/debatte/kommentare/article196058637/Juedisches-Museum-Sinnbild-und-Opfer-eines-deutschen-Missstands.html. |

| [8] | Felix Axster, “War doch nicht so schlimm,” Der Freitag, no. 22/2020, May 25, 2020. https://www.freitag.de/autoren/der-freitag/war-doch-nicht-so-schlimm. |

| [9] | See Armin Langer, “Der Antisemitismusbeauftragte unter Judenfeinden?,” Zeit Online, June 5, 2020, https://www.zeit.de/gesellschaft/zeitgeschehen/2018-06/felix-klein-antisemitismusbeauftragter-bundesregierung-demo-evangelikale. |

| [10] | Adam Soboczynski, “Für eine Entschuldigung sehe ich keinen Anlass. Ein Gespräch mit Felix Klein,” Die Zeit, no. 22/2020, May 19, 2020, https://www.zeit.de/2020/22/felix-klein-holocaust-achille-mbembe-proteste. |

| [11] | Felix Axster, “War doch nicht so schlimm.” |

| [12] | A differentiated overview, critical toward Mbembe, of the relationship between postcolonialism and Jewish thought has been provided by Caspar Battegay: “Postkolonialismus und jüdisches Denken. Anmerkungen zur Debatte um Achille Mbembe,” Geschichte der Gegenwart, May 13, 2020, https://geschichtedergegenwart.ch/postkolonialismus-und-juedisches-denken-anmerkungen-zur-debatte-um-achille-mbembe/. |

| [13] | Felix Axster, “War doch nicht so schlimm.” |

| [14] | “Rede von Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel vor der Knesset am 18. März 2008 in Jerusalem,” https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/service/bulletin/rede-von-bundeskanzlerin-dr-angela-merkel-796170. |

| [15] | Christine Kensche, “Mbembe sollte nicht so behandelt werden, wie er uns behandelt hat,” Die Welt, May 14, 2020, https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article207972035/Antisemitismus-Vorwuerfe-Professorin-Shifra-Sagy-ueber-den-Fall-Mbembe.html. |