POSITIVE CONTAMINATIONS Delphine Horvilleur in Conversation with Isabelle Graw and Dirk von Lowtzow

Clarice Lispector in Bern, 1940er Jahre

DIRK VON LOWTZOW: How do you experience the current anti-Semitism in France? Is it something that has risen in a way that has been noticeable for you? And if yes, how strong is it?

DELPHINE HORVILLEUR: We belong to a generation that believed the issue of anti-Semitism to be a problem of the past. I grew up in France in the ’80s, where it seemed that it was behind us. We were raised on this idea that we were lucky to be born in a time when the historical trauma was so close to us that we could actually assume a kind of generational immunization from anti-Semitism. But this started to change in the ’90s. In France, there was the event in Carpentras, the desecration of a cemetery in the South of France. I clearly remember learning about this event in the car. My dad was driving, and I was sitting next to him. His face changed and he told me that it was probably the worst or the most serious historical event that I had been confronted with. I started to realize that maybe the ‘immunization’ theory was wrong and that we would have to face this phenomenon in other forms. When I think about anti-Semitism in recent years, I could point to specific dates, which we all remember in France: for example the assassination of Ilan Halimi, in 2006. At the time, I was pregnant with my first son, and I remember walking in the streets of Paris in the midst of this demonstration that happened after Ilan died. I was looking around me and noticed that there were mainly Jews participating – the Jewish community was around but we were pretty lonely, which was different to Carpentras. At that time, France had been in the streets, even François Mitterrand was there, too. In the beginning of the year 2000, Jews started to talk about anti-Semitism being on the rise; people told us that we were exaggerating, that it was a kind of Jewish paranoia, that we were only dealing with an import of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or inter-communitarian tensions and that it wasn’t truly anti-Semitism. And then came 2012, the year of the Toulouse and Montauban shootings, and other targeted killings in recent years, like the Hypercacher kosher supermarket siege in 2015. It seems to me that anti-Semitism was always there, but its prevalence became clear to more and more people, not only to the Jewish community. It was on the rise and it was speaking a new language, which was actually the same old one, only expressed through new actors.

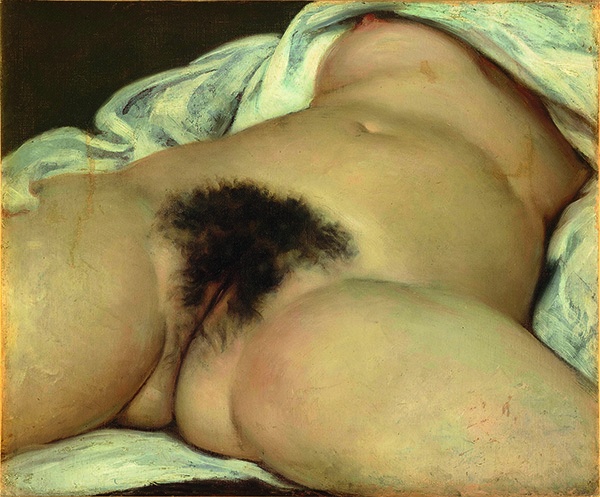

Gustave Courbet, „L’Origine du monde“, 1886

ISABELLE GRAW: It’s interesting to hear how you were told that the fear of a rise of anti-Semitism was exaggerated. It reminds me of a recent excellent biography (by Wolfgang Emmerich) of Paul Celan – Celan experienced anti-Semitism in Germany in the 1950s in many facets, but his friends and colleagues told him that he was exaggerating, that he was paranoid. At the beginning of your book Réflexions sur la question antisémite you offer a very helpful distinction between anti-Semitism and racism by describing how racists hate ‘the other’ for what she or he doesn’t have, whereas Jews are hated for the opposite reason, for what they supposedly have. So, according to the anti-Semitic perspective, Jews embody something excessive, something de trop (too much). At the same time, you demonstrate very convincingly how Jewish identity has been marked by breaks and by a sense of not belonging. It was perceived as an identity that could neither be clearly distinguished nor fully integrated. And this is why anti-Semites, who usually have quite a painful relationship to their origins, feel so threatened and have so much resentment against Jewish people. In this sense, you propose a very useful notion of anti-Semitism as a kind of psychic structure that results from projective collective assumptions about the other. I immediately thought of Adorno’s and Horkheimer’s essay on anti-Semitism and their use of the term “false projection,” which they understand as a tendency to project those impulses onto the other that one cannot allow oneself to have. Adorno and Horkheimer also argued that it is capitalism’s wrong promise of equality that triggers delusional projections, because the anti-Semite projects himself into a position of power and domination while actually experiencing his own social impotence in capitalism. So, how would you register these two factors – false projection and capitalist economic conditions – into your notion of anti-Semitism?

HORVILLEUR: While listening to you, I was thinking about a sentence of Sigmund Freud, which I quote in my book, and which is related to what you just said. He wrote a note in one of his case analyses, saying that from his point of view, anti-Semitism always stems from a complex of castration. The complex of castration is a fear that anyone can have – not only male subjects, of course. It is the fear of losing integrity, authenticity, a fear of the porosity in your world. A fear that something might be open and remain porous, thus contaminating you or breaking you, making you feel less complete. It is a fear that has a lot to do with what you just described as capitalism: the will to be complete, which is also related to what has been said about authoritarian characters who are fearing loss or incompleteness. What struck me in my research is that, from the beginning, Jewish religious texts seem to be really aware of the fact that anti-Semitism always has something to do with precisely this fear of a lack of continuity and authenticity. And the texts are also aware of the fact that this has nothing to do with Jews, but everything to do with the person who expresses those threats or who fears those fears. We know that there is no need for Jews to be present for anti-Semitism to be present. They can be accused of being too rich or too poor, they can be accused of being too patriarchal or too feminist, they can be accused of inventing Jesus or of not believing in Jesus, they can be accused of being the system or threatening the system – and sometimes all these things at the same time. It has nothing to do with them, but everything to do with precisely the fear of decomposition, fragility, and vulnerability, which is an existential threat that a person, a tribe, a group or a nation is experiencing at a specific moment. And this is where we stand today. If we pay attention to political or religious discourse around us in the past years, everyone can notice how strongly this notion of completeness and authenticity and nostalgia for a fantasized complete past is operating both in the political field and in religious fundamentalism. We can hear it all around us.

But I want to go back to what you were saying at the beginning. I think it has been a mistake in recent years to say that in our society there are two categories of people: either anti-Semites or Jews – or anti-Semites and people who aren’t anti-Semites. I think it’s more subtle and complex than that. I would say that in our societies some people did hear anti-Semitism and some people didn’t. Because they didn’t want to or they couldn’t. But I realized around me that many people, at the beginning mainly Jews, started to develop an antenna: a way of hearing, sometimes even from very far away, the anti-Semitic discourse, and sometimes not proper anti-Semitism but a discourse that goes together with anti-Semitism, for example within conspiracy theories. With the latter, people try to find an explanation of what has happened to them by placing responsibility onto others: Europe, the government, etc. We know that this type of discourse always goes hand in hand with anti-Semitism because it tells the same story. It’s a story about your own lack of responsibility in what happens to you. Instead, you present yourself as an object of fate or put the blame onto someone else. I always have to think about this anti-Semitic caricature that occurs throughout history, always the same: a Jew, obviously with a big nose and big ears but especially with long hands. It’s supposed to tell you that Jews are in control. Having big hands means that they manipulate you, your fate, your children, your country, and your money. It tells you that you’re lacking any possibility to act, because someone else is in control of your failure. If you fail, it’s not because of you, but because of the controlling power. And this also points to the difference between racism and anti-Semitism: racism is about thinking that the other isn’t worth anything, is below or behind me and that I am above. Whereas, most of the time, Jews are accused of owning, having, controlling [everything].

VON LOWTZOW: So once anti-Semitism considers the Jew as marked by excess and lack at the same time, just like you said, a version of anti-Semitism can take place that you have equally described in your book, an operation that is at work in Germany, for example, to this day. It usually expresses itself latently along these lines: Germans will never forgive the Jews for the wrongdoing the former did to the latter, blaming them for the Holocaust, for the Shoah. How can this perverse inversion be prevented and stopped? Do you have any idea or solution?

Delphine Horvilleur auf dem Cover von ELLE France, 2020

HORVILLEUR: I wish I had. But this always brings us back to the question of how you train and how you teach responsibility. I have no idea. And I’m not even talking as a rabbi or a writer, I’m talking as a parent. As a parent to two teenagers, it is a real question: How do you teach someone that they have a responsibility over what they do and what happens to them? It is very difficult, maybe even more difficult today in the era of “victimhood competition” as we say in France. While it is of course important to be allowed to speak about your experience as a victim, there is a current tendency to essentialize victimhood. Simply by belonging to a group that suffered, you are supposedly the heir of a tragic story – even when you didn’t suffer personally. It’s like an aristocratic title, something that gives you rights. Often this comes with the idea that the other has to symbolically pay back for a failing and painful history, a history that is supposedly mine. [But] we all know that having suffered doesn’t give you any paricular rights. It sometimes gives you a specific sense of history or a specific sense of heritage. Sometimes, and this can be painful, it gives you a specific duty to act in the world. But I don’t think it gives you any right. This is something we really need to pay attention to. We are lucky to live in a time where victims of various crimes are finally given access to words. We can make sure that this access to the word victim doesn’t enclose them or jail them or lock them into the status of a victim, which doesn’t give any rights. It’s supposed to teach you something about history and to transform you into being a specific agent of something in the world. I’m not sure whether I’m answering the question clearly, but I think for me the only answer is: we need to find a way to strengthen this notion of responsibility and what we teach.

GRAW: In your book you criticize so-called Critical Whiteness along these lines – for its tendency to hold individuals responsible for what their collective has done. I agree that it’s quite important to realize how one might unconsciously reproduce class and group privileges, and I would like to know more about this. I was wondering how one could practice such a rejection of individual responsibility for one’s collective on the one hand while still reflecting on one’s own reproduction of white privilege on the other. How can we put these two together?

HORVILLEUR: I think that today we experience an inflation of the “we.” More and more people say “we,” and even when they say “I,” they do mean “we.” It has been particularly strong in France; I think it has been less the case in Germany, because historically its heritage is not the same. The heritage of the French Revolution and the French Republic is the promise that people would be able to say “I” in all circumstances. There is no recognition of communities in France but only the recognition of individual rights. But with the rise of what we call communitarianism in France in recent years, many people have been saying “we” in all occasions: “we, the Jews,” “we, the Muslims,” “we, the gays,” “we, the women.” There is a perception or a fake impression that the “we” is a monolithic category. Jacques Derrida used to say that “we” is always an abusive language. Because when you say “we,” you speak in the name of someone who didn’t ask you to. And I do feel this way, when people say “we, the Jews,” I always think, “Are they talking about me? Are they including me?” It’s an abusive language because this language has a presupposition that the Jews think, eat, vote, behave or practice in one way, and we know that this is not only not true but it’s particularly not true in the Jewish world. You probably know this old Jewish joke that says when you ask a question to two Jews you’ll get at least three or four answers. And it’s particularly true when you ask them about Jewish identity. If you were to ask me today what Jewish identity is about and ask me the same question tomorrow or yesterday, I would probably disagree with myself. I have no definition of what it means to be Jewish, which is another issue and has to do precisely with anti-Semitism. There is an inflation of the “we” phenomenon that I think is particularly dangerous today. It’s at stake everywhere and I try to denounce it in the book. I would say that it’s the same old language of the extreme right, to emphasize the ”we” as a collective identity that should be preserved: the idea that the nation or the culture should be preserved from strangeness, from invasion of the foreigner, and we should go back to what we were and should be in our authenticity. But what is new is that this idea resonates strongly in a certain language of the left and of the extreme left. I am thinking of the idea that we should go back to our indigenous identities in a preservation from what has been the contamination of colonialism and whiteness. I’m aware that it is a dangerous path that I’m walking on when I’m saying this, because I can easily be misunderstood. I truly believe that it’s very important to hear those voices that have been silenced across history. And we have a duty to finally hear these voices of otherness that were muted in our society for centuries. But at the same time, we need to make sure that these voices don’t become as violently monolithic as other voices have become. That they are not suddenly developing another discourse of authenticity and purity, which has been the discourse of the extreme right and suddenly becomes a discourse of the left.

I also realize that everything I’m writing about, from my first book until now, is about the same notion: How do you fight the desire in yourself, that exists in each of us, to buy into narratives of purity? Each time you buy into a narrative of purity – the purity of your origin, the purity of your belief, of your group – you step onto a path to a dead end. Unfortunately, this is where we are now. I’m really afraid and concerned about the impact of the health crises that we are going through in the global pandemic. Because the idea of “contamination” and “remaining pure” and fighting the porosity of frontiers is everywhere around us when we talk about this disease. We need to make sure that as we fight this viral contamination, we’re able to bless the powerful contaminations of our identity. We are who we are because we have been contaminated – meaning, we have been fertilized by otherness, and we owe who we are to this other that stands not only inside us but stands at our origin. The definition of an anti-Semite is someone who is not willing to see what he or she owes to this core of otherness. Theologically, Judaism – because it has to do with the origin of Christianity and Islam – has paid a very high price for being linked to this origin that you don’t want to see. I always think about The Origin of the World by Gustave Courbet, where we see the female genitals. It’s interesting that the title of the painting is The Origin, because it’s something you don’t want to see. You don’t want to know that this has something to do with where you come from. And I think that anti-Semitism is a fear to acknowledge that you’re in the world because there has been a fertilization. If there was no encounter with otherness, none of us would have been born.

VON LOWTZOW: You were mentioning the coronavirus health crisis and in your book you describe how anti-Semitism uses misogynistic tropes, for instance when Jews are described as effeminate, weak or hysterical. This made me think of another trope that depicts Jewish femaleness as syphilitic, as a danger of disease for the male ‘Volkskörper,’ something that the German writer Klaus Theweleit described in his 1977 book Male Fantasies (or Fantasmâlgories, in the French edition from 2016). This notion seems to be particularly relevant in times of the coronavirus, where anti-Semitic conspiracy theories once again flourish.

HORVILLEUR: Absolutely, we hear it coming from very different landscapes. The idea that Jews are able to contaminate has been a strong theme since the Middle Ages and often gets related to the old contamination diseases throughout history. Sometimes it’s not even a sanitary or a health theme but a political one. In Pittsburgh, two years ago, when the killer stepped into the synagogue and people tried to understand his motivation, he said that American Jews were polluting the American soil by aiding migrants. Same thing last year in Halle, at Yom Kippur: the guy who tried to commit this terror attack accused the Jews of being linked to the feminist revolution and the idea that there is a contamination by femininity. We always go back to this idea of two visions of the world: Do you believe that the frontiers of your country, of your nation, of your mind and of yourself have to be hermetically closed so that you can be yourself? Or do you believe that it’s because your world is porous that you can be yourself? Actually, both beliefs are true in a certain way, just like our skin is both closed and open. This is how organisms live. The discussion around open or closed frontiers is everywhere around us. Should Europe reopen its frontiers? We will probably witness an opposition between two schools of thoughts in the coming weeks. Are we safer in a world in which every nation locks itself? Or are we safer in a nation that is able to consider true collaboration – which implies a contamination of ideas, a fertilization of minds? To an extent, France and Germany have often been true models of that. There were incredible stories of medical help between the countries. Our two countries actually do know that they have the power to be a model for Europe or maybe even for the world: a possibility for a powerful opening of the mind’s frontiers. We could witness this story go one way or the other.

GRAW: Yes, it could go both ways. To pick up on what Dirk just asked you about misogynistic tropes in anti-Semitism: in your book you also pointed to the correlation between the crisis of maleness in the 1920s and the rise of anti-Semitism at the time. Do you think that we are witnessing a similar constellation nowadays, especially considering how many heterosexual men (on the right and also on the left) seem to feel threatened by the #MeToo movement? Are we dealing with a similar crisis of maleness or is it different due to the specific power (and threat) of the #MeToo movement?

HORVILLEUR: I’m going to give you a very rabbinic answer: yes and no. Now I have to scratch my beard [laughing]. The accusations against Jews and women have been the same all along history. If you listen to what Jews have been accused of, for example their hysterical behavior, their love of money, and their love to be in contact with power or powerful people – all these accusations are pure misogyny. For others, women and Jews embody this weird association of being like one’s self and the other at the same time: having to do with one’s origin but being different. They have power yet have no power and are accused of being controlling and manipulating, but at the same time they face a lack of sovereignty and political power. This is still true in many ways today. In current anti-Semitism you also still find all these elements.

What makes things complex today is that we witness accusations against Jews precisely for their patriarchal and sometimes even virile power they suddenly represent in a time where feminism is on the rise. And a perfect example for that illustration is hate against the state of Israel. It is interesting that Israeli Jews are suddenly accused of representing the soldier, the virile force that goes against a certain image of the powerless, almost feminine, figure of the Palestinian fighter. It tells you something about the amazing muting capacity of anti-Semitism and its capacity to adapt to a new ideological mainstream. It’s a losing game and we know it. This points to the maybe pessimistic conclusion of my book: there is no way we are going to get rid of anti-Semitism because Judaism and Jewish identity have an amazing capacity of being so plastic that they can constantly redefine themselves and guarantee that Jews will always be around, which is pretty annoying for anti-Semites. And anti-Semitism possesses the same plasticity and is able to adapt. Sometimes, at the same historical moment anti-Semites are able to accuse Jews of the one thing and its absolute opposite. It’s been striking to see in France in recent years, just like all around the world, that Jews are associated with a dominant class. But at the same time they’re killed in supermarkets and schools. How can assassinated children at the same time be figures of domination? This is happening all around the world and it is very depressing.

VON LOWTZOW: You said you gave a rabbinic answer, which brings me to another question. How does your rabbinate work? Is your practice an exegesis of texts, like a literary seminar, or is it more like a ‘proper’ service?

Martin Kippenberger, „Ich kann beim besten Willen kein Hakenkreuz entdecken“, 1984

The other part of my work that I’m deeply attached to is to teach beyond the Jewish community. This is what I have been doing for years now and it’s been strengthening during the past weeks due to the confinement and the health crisis. We developed a weekly class on Facebook through my magazine, Tenoua, which means “movement” in Hebrew. Every Tuesday we meet for “Tenou`alive” and I have been so moved by the number of weekly participants in this Talmud class on Midrash, rabbinic literature, the Talmud, and Hebrew. And in recent weeks we have reached 70,000 followers. It was crazy. And obviously, most of them aren’t Jews: there are Muslims and Christians and atheists who want to study with us. For me that is very moving. When my book was released last January in France it became a bestseller quite quickly. I was moved when I was watching people reading Midrash in the Paris subway. People very often believe that religious thoughts and particularly Judaism are a very private territory and that Jews are not willing to open the gates and that it’s all between themselves. I think this is so untrue. Judaism and Jewish thought are a particular language. I don’t believe in syncretism. I don’t think that Judaism, Islam, and Christianity are saying the same things. They don’t use the same terms or the same language. But they do have a voice that can contribute to a collective discourse and a true dialogue – sometimes with disagreements and failures of communication. But it’s a powerful possibility to build bridges and contaminations – but positive ones, the ones we need today. I try to contribute to this dialogue. To answer your question, I am very attached to my rabbinic work and the possibility to be both: a pastor and a teacher.

GRAW: I wondered about the status of women in Jewish texts, in the rabbinic literature. This is something that is not very much discussed in your book. I always thought that Judaism is a religion which can be described – like most religions – as rather patriarchal.

HORVILLEUR: This was the topic of my first book, which I hope will be translated into German soon. In French it’s called En tenue d’Ève: Féminin, pudeur et judaïsme, meaning “in Eve’s garment.” It’s about the figure of the woman, about femininity and the obsession with modesty, that exists in Judaism just like it exists in all monotheist religions. The trend today in many branches of religious feminism is to suggest that religions are actually more feminist than we think. And I think this is not true. I think religions are deeply immersed in a very patriarchal heritage, where the woman was always the other, the hidden, the eclipsed agent. But I do think that our traditions are calling us to question them in the name of justice and to make room for otherness. In the name of responsibility they are asking us to question this heritage. If a tradition wants to be alive, it constantly needs to accept a certain violence directed against itself. Because what we experience today, in this context, has never been experienced before. We do live in a time where women and femininity play a role in our society they never played before. I therefore think: if religions want to stay alive they need to take into account this never-before-experienced situation and establish a dialogue between our time and our heritage. That’s the condition of a living tradition. It needs to be constantly reinterpreted, questioned. And when it’s not, it’s dead.