ON JENNIFER C. NASH’S “BLACK FEMINISM REIMAGINED: AFTER INTERSECTIONALITY”

“The Feminist” is a decidedly singular noun. Yet my development as “a feminist” is deeply indebted to plurality, to countless professors and authors and books and artists. I can trace the genesis of my feminist consciousness to my undergraduate study of what was then known as “Women’s Studies.” The formative moment, however, came in my final semester in a requisite class called Varieties of Feminist Theory – here, again, an emphasis on plurality.

The class was taught by Jennifer C. Nash, known to students as Jen. I dug up the syllabus in preparing this text. In it, Jen wrote, “I am here to guide us through a set of texts that seek to do nothing less than to reimagine everything about the social world.” Jen not only guided us, she fostered a community within and beyond the classroom. And through the texts I not only reimagined the social world, I was fundamentally transformed: in how I understood myself, how I approached academic work, how I practiced politics.

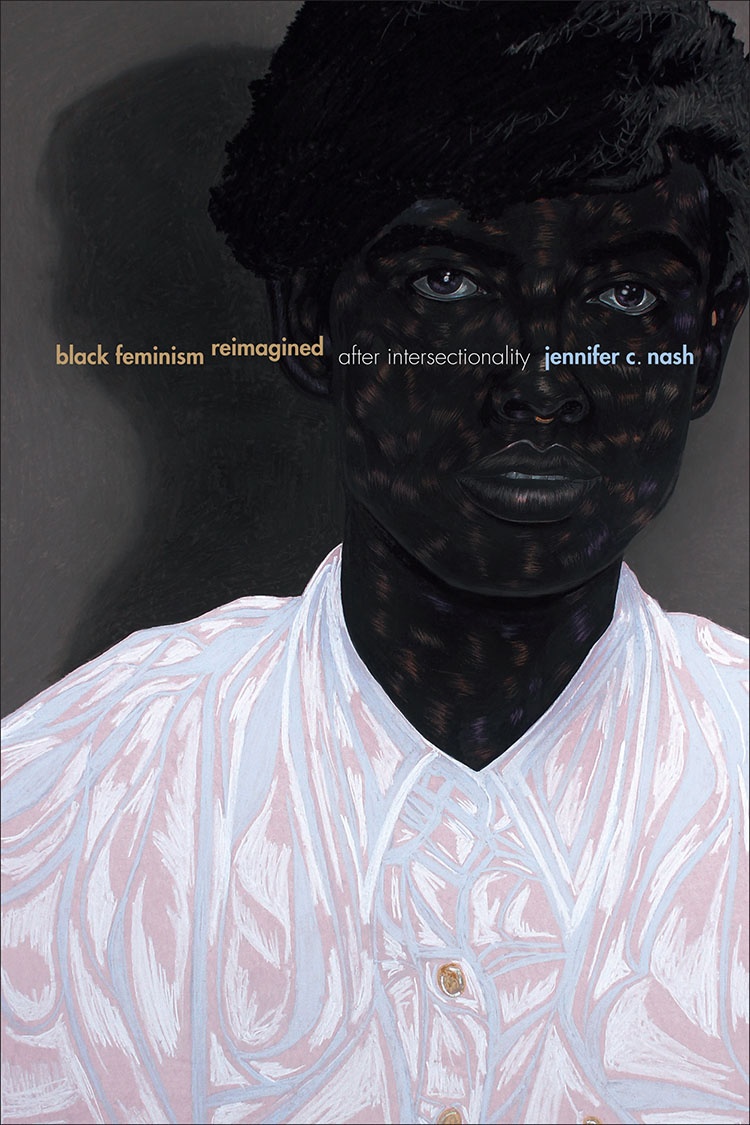

For this issue of Texte zur Kunst, I chose Jen’s 2019 book, Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality. It examines the application of intersectionality and the intellectual labor of Black feminists in the US university, their uses and misuses in the academy, and their relationship to “Women’s Studies.” The book’s central project is to reframe Black feminism as “a practice of freedom.” [1] Jen closes the book with an appeal to readers, to feminists, to acknowledge Black feminist theory’s project of utopian world-making and to challenge “Women’s Studies” to reflect critically on its history and attachments. For the purpose of this issue’s project, the book is less an “object” for discussion than a prompt to reflect on, and then write about, my feminist subjectivity, tied up as it is in my experience in “Women’s Studies.”

The applications of Black feminism Jen writes about in her book were integral to the curriculum for Varieties. In class, Jen urged us to participate in utopian world-making and political dreaming; she urged us to apply the theory of our readings to real political action, encouraging us to “take it to the streets, feminists!” What I understood as falling under the purview of “Women’s Studies” as a discipline or “Feminist” as an identity expanded radically. Feminism, in its most expansive variety, became a lived, embodied practice. I continue to return to the texts we read, and they continue to accompany me as I move through the world.

The nostalgia embedded in my writing here is, to an extent, a result of the influence of affect theory in Jen’s book and in her syllabus. It’s not often that academia takes up, let alone promotes, affect and its real uses. In the book, in a section titled “Loving Feminism,” Jen writes,

If our survivals are mutually dependent, we are, then, mutually vulnerable, as our thriving requires our coexistence. To act in love, with love, is to recognize this mutual vulnerability as something that must be not eschewed but rather embraced, as a necessary positionality to the project of social justice. Put differently, a commitment to mutual vulnerability constitutes a commitment to be intimately bound to the other (or to others), to refuse boundaries between self and other. [2]

This understanding was central to Varieties. The class was a space of collectivity and empowerment and care, and it established for me a model of feminism in practice. As such, it instilled in us – in myself and my peers – this mutual vulnerability and intimate boundedness. It defined for me what it means to be a feminist. This is in part why I still feel so connected to Varieties, and why I felt an urgency to read Black Feminism Reimagined as soon as it was published. I ordered a copy somewhere online, certain I wouldn’t find it in Berlin. Not long after I finished the book, it appeared on display in my neighborhood bookstore. I emailed a picture to Jen, bound still to this community, years later and thousands of kilometers away.