A comedic utterance is difficult to translate into visual language. Art that attempts this must pin down an otherwise fleeting moment, preserving it in concrete form, and captures something beyond the utterance and its specific context. The visual reminder, what art historian Jennifer Greenhill calls “scrawly comedy,” circumvents the punchline’s finality and draws out a joke’s temporality, recalibrating the material for different effects. Here, Greenhill weaves a historical account of this strategy with the contemporary artistic practices of Glenn Ligon and Martine Syms and argues that art about comedy may offer a model to challenge sociopolitical precedents, especially those embedded and reproduced in the comedic.

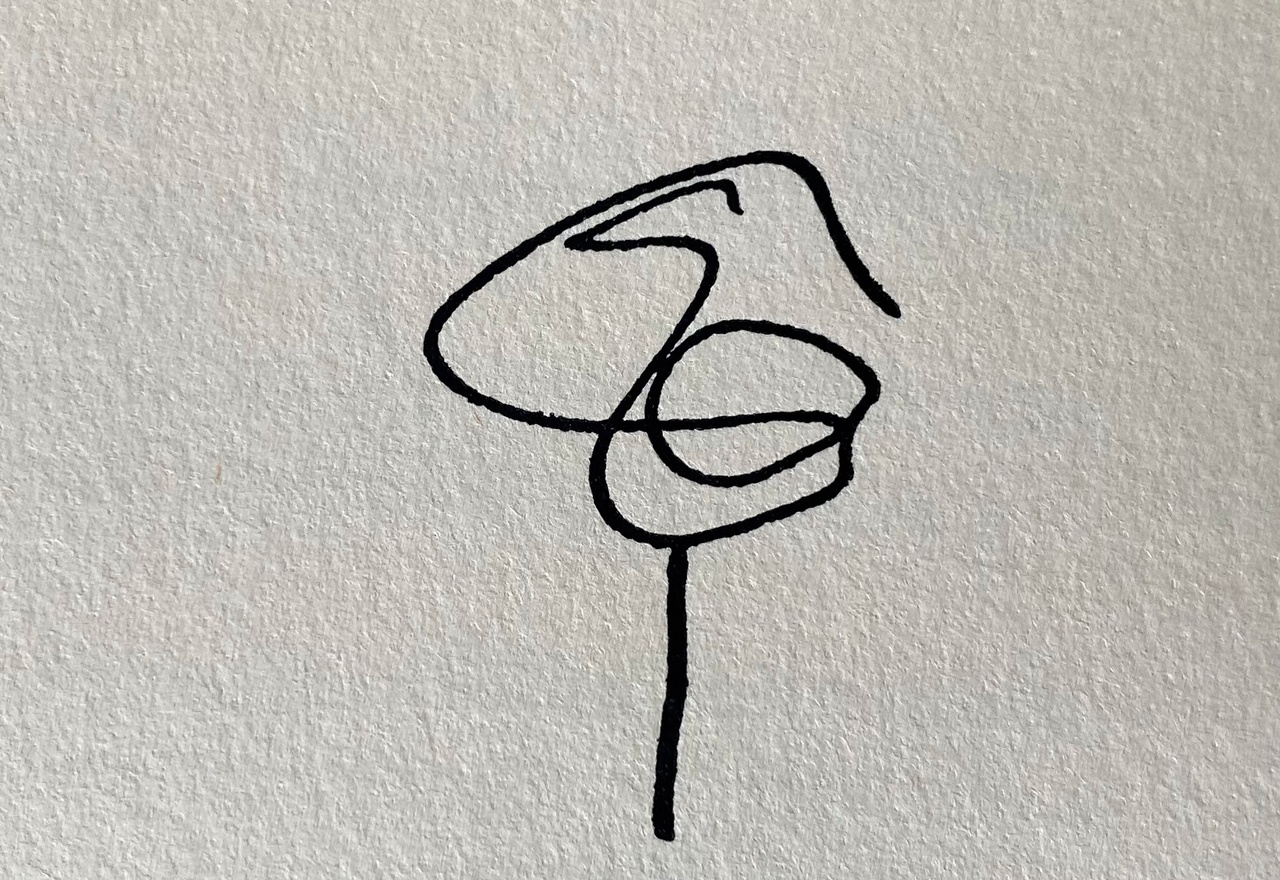

In a short chapter of Enjoyment of Laughter (1936) entitled “To Diagram a Joke,” the American Marxist writer and activist Max Eastman devised a graphic system for categorizing different sorts of comic utterances. The “mere ludicrous word or image” lacking a discernible point Eastman represented “by a scrawl with nothing but a stem to hold it up.” A straightforward narrative setup could feed into such a pointless “poetic absurdity” by “collaps[ing] into nonsense.” In Eastman’s graphic language, this is rendered as a long horizontal line that abruptly alters course as a backtracking, broken diagonal pointing toward the circuitous scrawl. If many humor theorists of his day tended to fixate on the resolution offered by punchlines and the larger meanings of “joke patterns,” Eastman looked at humor as if under a microscope, training his eye on its molecular components. The scrawl was just one “infantile atom” among a multitude of charged particles animating the disorderly worlds of comic expression, but it was Eastman’s favorite. “In anything that is funny some element must remain scrawly, remain broken, unorganized into a pattern,” he argued, visualizing this resistant discontinuity with a line that turns back on itself in a tight and self-contained formation. Never the same formation twice, Eastman’s scrawl can look as elegant as a minimalist wire sculpture or read like a dense knot of clotted doodling. It is the wildest and most variable unit in his lexicon, a figure for going nowhere yet one that takes multiple paths for getting there.

There are many ways to do scrawly comedy, which I see as a method of transforming an existing comic utterance into a new visual formation that only pretends to analyze, dissect, and clarify. Scrawly comedy is a way of generating a comic remainder – of an insistently visual sort – out of a joke already told in another time, place, language, medium, or format. In excess of the original utterance, that visual remainder is more attuned to form and framework than to content. In restating and restaging existing jokes in alternate historical and material contexts and drafting them into the service of visuality, scrawly comedy tends to focus on the stuff that would seem to be beside the point of the punchline (even when punchlines are the ostensible subject). It circumvents the punchline’s finality for a more meandering path around and through the punchline’s concision, kicking up dust and disturbing the firmament of even well-worn jokes in the process. They look different through this atmospheric interference, more like impenetrable riddles than the stock one- and two-liners we may have heard so many times before.

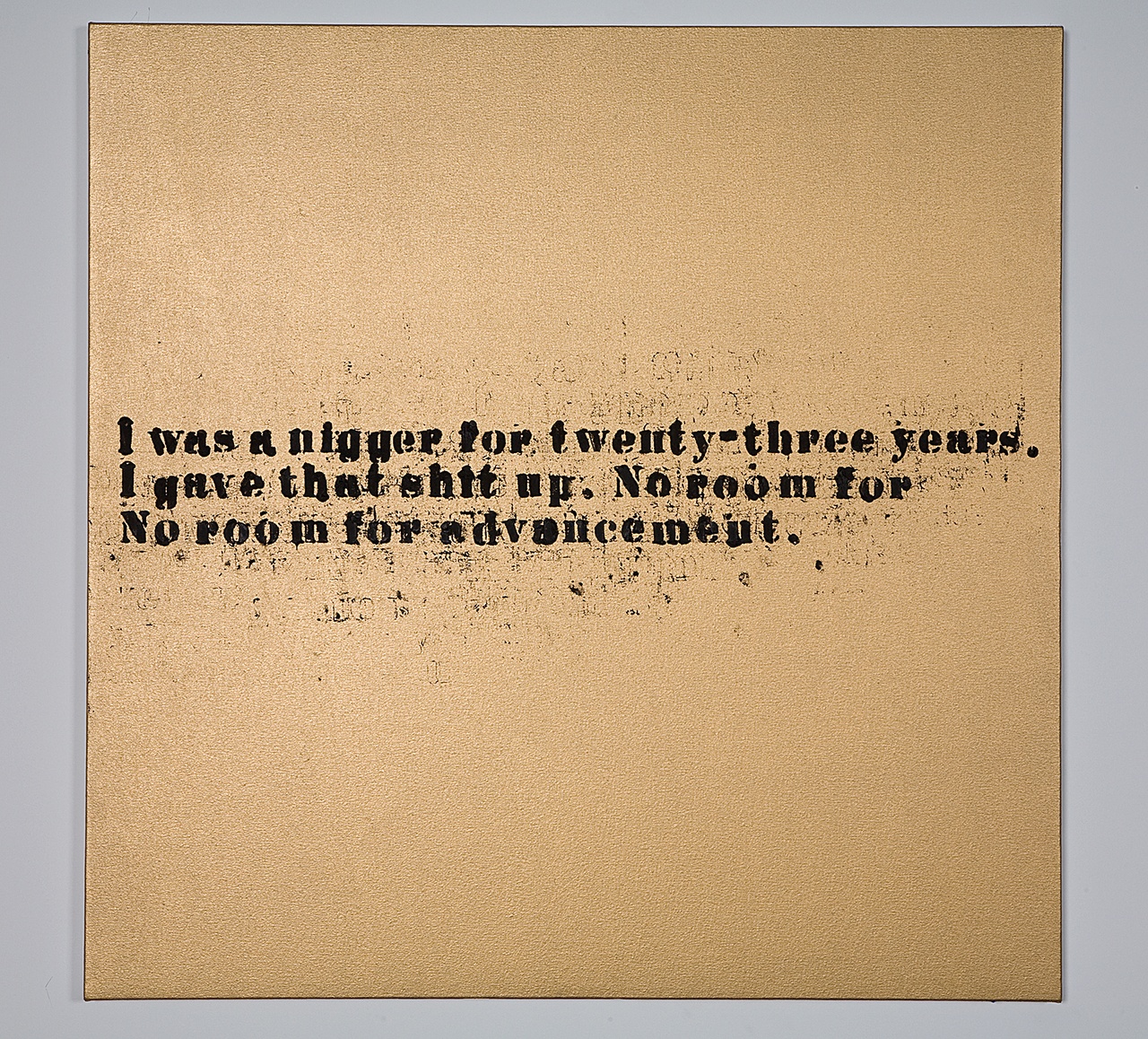

Glenn Ligon’s video installation Live (2014) and text paintings devoted to Richard Pryor’s stand-up (the first dating from 1993) seem to me wired by the circuitry of the scrawl. The paintings riff on Richard Prince’s joke paintings of the 1980s, but they are literally rougher around the edges, with oil stick pressed unevenly through stencils and stark critiques of American society voiced by a complex comedic persona. Sex, drugs, morality, and racism were the raw material for Pryor’s raw performances in his heyday of the 1970s and early 1980s. There is something fitting, then, about Ligon’s registration of all of that edgy content in text that does not always line up, that feels literally heavy in some places, with thick encrustations of paint, and looser in others, as though blowing off steam. If Pryor was a “charismatic and confusing presence,” a “person in process,” as one scholar has argued, Ligon’s series takes up a processual choreography, in some cases retracing the beats of a single Pryor joke in dozens of canvases.

The repetition reads as an effort to know and understand, to be in the presence of the comic artist and learn the secrets and substance of his craft. But it also reads as an effort to conjure, and compensate for, what cannot be adequately bodied forth by the transcriptions of text alone: the tone with which the lines were uttered orally; the cadence, pacing, and volume of the comedian’s delivery; the gestures that accompanied, distracted from, or underscored a point; the sociality of the comedy club, the laughter that buoyed a bit forward, and the applause that punctuated a punchline.

In the No Room (Gold) paintings (2007), Ligon approximates Pryor’s delivery with the abortive fragment that trails off after the end of the second line, “No room for.” The final line then finishes the thought, putting a period on the punchline: “No room for advancement.” The artist is asking us to hear something like improvisation and emphasis in the reiteration, perhaps a response to the energy coming from the audience. The space that follows the “for” at the end of the second line gives room for a pause – the silent cliffhanger before the punchline touches down – thus bringing comic timing into the canvas. The faint trace of letter forms not followed through, which hover above and below the black text in many of the No Room (Gold) paintings, offers some light visual noise to further amplify the painting’s aurality. Ligon is not really trying to dissect Pryor’s comic material or truly translate the inimitable, unknowable Pryor according to his own visual lexicon. He is, instead, I believe, offering a manifestation of Pryor that is just short of adequate to the task but no less mesmerizing. And that means building inimitability and unknowability into the symbolic visual registration of comedic voice. A scrawly conundrum with no beginning and no end.

Ligon’s joke paintings play on one of the most cherished binaries of writing on humor, which situates the joke uttered on the breath on one side, and the joke dulled by the printer’s “cold dead types” on the other. “In representing a live lecture, bristling with gesture, genuine eloquence, or mock oratory, the cold dead types can convey but a vague idea,” argued one humorist turned critic in the 1890s. Yet the mere effort of taking a joke that had been freely discharged orally and committing it to a durable and enduring form like print seemed perverse to some late 19th-century critics who believed they were living through a “plague of jocularity.” But how else to transmit a comedian’s act beyond the stage for future generations?

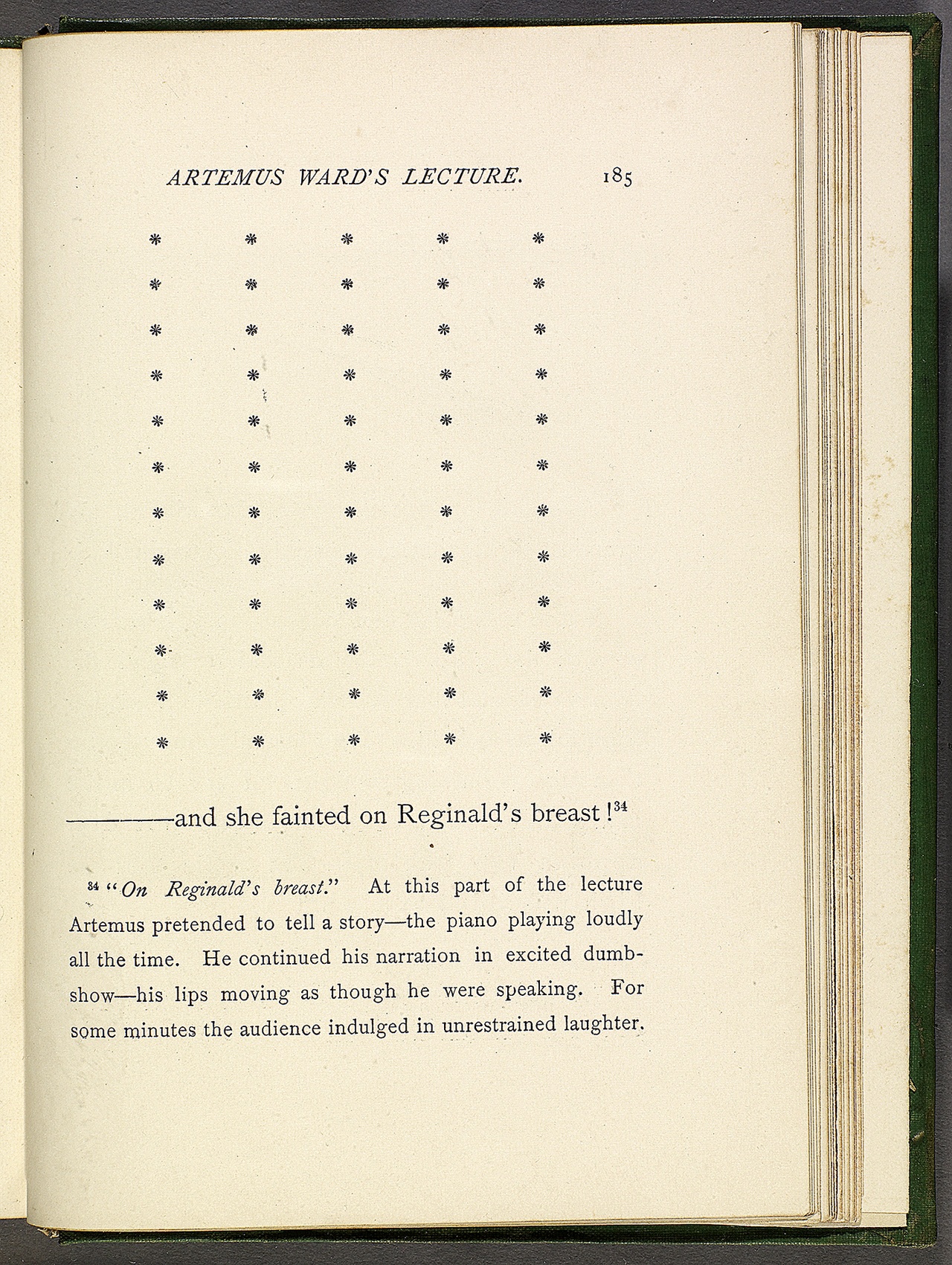

When the American humorist Artemus Ward (born Charles Farrar Browne) died on tour in Britain in 1867, the executors of his estate endeavored to transcribe his act in an experimental little volume that privileges joking tone and delivery. This was a special challenge, since Ward’s meandering, deadpan storytelling often baffled audience members taken in by his serious tone and convincing performance of ineptitude. Ward’s editor-interpreters attempted to meet the challenge by varying their type according to how the comedian delivered specific lines: if he drew out a line or uttered it under his breath, the spacing and sizing of the letters on the page reflect this, with miniscule letters trailing off at the end of lines to communicate the volume of Ward’s voice, for example, and rows of asterisks marking chunks of time during which he remained silent – Tristram Shandy adapted to the world of mid-19th-century American comedy. Editorial glosses at the bottom of pages work to transmit the sociality of the theatrical event for later readers by noting which remarks set the audience into fits of laughter and for how long the guffaws rippled through the venue. The little book’s surfeit of explanation and typographical expressivity is clearly compensatory, making all too clear the difficulty of conveying, on the page, a comedian’s delivery and the laughter it inspired. Such strenuous efforts to get a handle on Ward’s complex comedy thus produced a book every bit as circuitous and opaque as the deadpan storyteller’s act. It is a fitting result, since the book therefore ends up preserving Ward as a comedic conundrum.

This is one way to respect the art of comedy – by retracing the comedian’s steps and reveling in the wild paths delineated without wearing down the road, so to speak, in the process. Ligon’s extended study of Pryor achieves this balance, I believe, particularly in the seven-channel video installation, Live, which debuted at the Camden Art Centre in London in 2014. Drawing on footage from the 1982 film Richard Pryor: Live from the Sunset Strip, the piece reverses the terms of Ligon’s joke paintings to investigate, as the artist explains, “what is left over when there’s not language.” That remainder is insistently visual as Ligon explores the expressive physical labor of comedic performance, parceled out into discrete visual units. Digital projections on seven screens of various sizes are organized in a roughly circular arrangement to surround the viewer, with six of the large screens focused on different parts of Pryor’s body – his head, mouth, groin, left and right hands, and his shadow. These details are isolated and tracked to remain centered on the screens, which at times appear to offer an ever-so-slight shift in perspective and at other times appear discontinuous. One small screen situated on the floor and at the periphery shows Pryor’s figure in full, but only intermittently, between periods when the screen goes dark. These interjections of visual silence occur at unpredictable intervals across the installation, between flashes of the comedian’s fingers carving forms in the air, or his mouth voicing a punchline we cannot hear. There is no sound in Ligon’s installation. As viewers shift position to catch the glimpses of Pryor that briefly materialize around the space, they may attempt to read his lips or search gestures for the punchlines that crossed the bounds of period propriety by veering into the scatological and risqué and tackling, head on, the grotesquerie of American racism.

Live from the Sunset Strip is a classic in the Pryor canon because it marked a comeback following the freebasing accident that left him badly burned, which Pryor later acknowledged was an attempted suicide. Tragedy lives within Pryor’s comedy, which the silence of Ligon’s installation might be said to bring out. When the piece was shown in Los Angeles in 2015, one critic argued that the “violence” of Ligon’s “almost Cubist” fragmentation of Pryor’s figure on stage might be seen as “echoing [American] culture’s fixation on certain parts of Black men’s bodies.” The logic of that reading feels especially resonant today, thus amplifying the tragic connotations of an installation that fractures the man and renders him voiceless. But this does not tell the full story of Ligon’s painstaking inquiry into Pryor’s art form in Live. Ligon’s Pryor is intensely alive in the present (and not just “live” on the Sunset Strip circa 1982) because he conspicuously exceeds the artist’s effort to take his measure. Live brings new qualities to the fore, such as delicacy, as the comedian’s hand flits and quavers, perhaps to underscore something said but possibly obeying its own logic. Ligon moves such incidental gestures from the periphery to the center of our focus, while also decentering viewers who cannot find a single position from which to take in a Pryor who is split into kaleidoscopic shards of expressivity. That expansive fracturing makes shortcuts to analysis impossible: suddenly Pryor resists categorization while registering as greater than the sum of his parts.

One of Ligon’s key moves in Live was to excise the 1982 film’s cutaway shots of audience members laughing and applauding. In Ligon’s restaging, Pryor gesticulates and snarls onstage without these interjections of approbation and surprise. I do not mean to suggest that audience response is absent or unfelt in Ligon’s installation; indeed, the periods when the screen goes dark eerily register the laugh from the past, all the more so because that laugh exists within, or is symbolized by, visual voids of varying duration. It is not so much that we cannot understand the laughers of the past – for Pryor remains searingly relevant and hilarious, even (especially) now – but that the historical laugh is strange and mysterious, unnatural by having endured beyond its original time and place. What is rarely remarked upon, however, is how Ligon’s dark screens conjure that strangeness. In contrast to the canned laughter of TV sitcoms, which package the laugh to mechanically jump-start later audiences, Ligon’s dark screens do not coax any particular response, though they do seem to ask to be seen. Functioning something like intertitles for this silent film, they reiterate the installation’s non-narrative visuality. Pryor’s jokes hang silently in the space without the finality of laughter-inducing punchlines. The linearity of any particular storyline is subverted for a messier visual array of comic physicality. It is not that Pryor’s routine goes nowhere in Ligon’s hands, but that it goes in so many directions – a scrawl in space.

For Max Eastman, the joke was “not a thing but a process.” His pretense of diagramming jokes was a ruse undertaken to show just how “much apparatus” and how “much worry” it took to convert “process” into “thing” – to essentially make it available to analysis. The scrawl was his graphic figure for “process” that would not be so converted. “You can not make a ‘thing’ of it,” he wrote triumphantly, making the scrawl the visual symbol for the kind of humor theory he wanted to do. If the scrawl was an “unpleasant” visual formation “to a serious brain,” its labyrinth-like inscrutability made it “naturally a good symbol of what is comic to a frivolous one,” he argued. Eastman’s terms are somewhat disingenuous here as he contrasts the seriousness of the scientific analyses to his own ostensibly frivolous investment in jokes. To approach comedy frivolously was, for Eastman, a serious project of tuning in to its formations and implications without imposing artificial restrictions that would impede the flow.

This is the sort of attunement that maybe only artists can achieve by thinking alongside (instead of analyzing) jokes of the past and activating (instead of mobilizing) comic precedents in their art. This is, I believe, what Glenn Ligon does in circling back to Richard Pryor again and again. The artist’s project is to “build with” the comedian, and not to “grasp” him, we could say (drawing from Édouard Glissant). Acknowledging the “radical alterity of the past” is central to scholarship in Black studies seeking to respect the historical subject’s right not to cohere or “represent” in any politically expedient way. Comedy is far from the concerns of such scholarship. But contemporary art about comedy may offer compelling support for – and a model of – “a cultural criticism willing to moderate its epistemological ambitions.”

Consider Martine Syms’s four-channel video installation SHE MAD: Laughing Gas (2016), which thinks with Edwin S. Porter’s 1907 silent film Laughing Gas to explore the physicality of laughter and the absurd circularity of the bureaucratic systems that legislate the individual’s movements in modern society. Already pumped full of nitrous oxide in the dentist’s chair, Syms – playing the role of “Martine” – is informed that her insurance won’t cover the surgery to remove her wisdom teeth. Does she want to use a credit card? Can she call her dad? Laughing to herself all the way home, while negotiating Los Angeles public transportation and the various doors and passageways of her Koreatown apartment building, Martine finally makes it to her sofa only to be called back to the dentist’s office, which has apparently sorted out the insurance issue. (“They want me to come back today?” she asks the person on the phone. “I can do it; I’ll be there.”) The effort it took to get home – which we experience with her in dizzying bodycam video – has been a pointless exercise demonstrating how the American healthcare industry jerks people around, particularly Black women, whom the system has repeatedly failed. But Martine can only laugh at the inconvenience – for she has literally been drugged to respond in this way. It is the sort of misadventure that would be met with canned laughter on a TV sitcom (and indeed Syms envisioned her Laughing Gas as an episode of a sitcom entitled SHE MAD, a conceptual project begun in 2015 with Pilot for a Show About Nowhere).

Throughout Martine’s zany but thoroughly mundane ordeal, we get glimpses of subjectivity as the primary narrative is interrupted by GIFs of Tyra Banks, Franklin from the Peanuts, Nicki Minaj, the android Data from Stark Trek: The Next Generation, and Smokey from Friday (“I don’t give a fuck!”), among others. The only figure we see multiple times is Bertha Regustus performing the role of “Mandy” in the 9-minute silent film from 1907. Regustus, who we see in close-up, alternately laughing or grimacing in pain with her palm to her cheek, is the glue that holds together these comic fragments of media-driven collective memory; she is the motivation for Syms’s work and also, I think, its true subject as a pathbreaker in cinematic history: one of the first Black female performers to be cast in a leading role. Syms’s four-channel piece stays close to the silent film’s linked vignette structure, which shows Mandy moving independently through public and private spaces, playfully disrupting them with her infectious laughter. Just as Mandy moves seamlessly from the dentist’s office to a tram car (where her laughter merges with the usual discombobulations of public transit), to the street (where she overturns a street vendor’s figurines) – and on and on – Martine moves seamlessly between her experience in real time to her experience as filtered through and commented on by digital memes.

This is the loose narrative structure of early cinema updated for our digitally vignetted lives. Although SHE MAD: Laughing Gas tells a seemingly straightforward story about a dental visit gone awry, it is rigorously non-linear and circuitous in the telling. As such, it rejects the racist narrative closure of the 1907 film, which situates Mandy, in the final vignette, in a Black church, where the physicality of her laughter blends in with the gesticulations of worshippers overtaken by “religious ecstasy.” One of the ways that SHE MAD: Laughing Gas dismantles this final punchline of Laughing Gas is by implying a return to the dentist at its close. The circularity of the narrative suggests an endless loop of merry and potentially hazardous meandering through worlds simultaneously experienced as real and virtual, as viscerally of the here and now but also as the residue of some elsewhere. These elsewheres, Syms suggests, are accessed through the media fragments that fill our minds. She takes that internalization to another level in her performance of Martine by activating the laughter of the historical media fragment through her own body, literally giving voice to the laugh of the past. Her work prompts us to examine the social and political implications of our exposure to and extension of structures of feeling originally packaged for another time, especially when comedy sets the terms.

Notes